Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Recommendations

- 3. Introduction

- 4. Part 1: Where we are

- 5. Part 2: Where we need to get to

- 6. Part 3: How we get there

- 7. Authors

- 8. Acknowledgements

Summary

- Strategic capabilities, such as vaccine development, robotics, and semiconductor design, are core components of national agency and prosperity. They allow countries to respond to crises and navigate geopolitics. But for too long they have been neglected in Britain.

- The Government’s forthcoming Industrial Strategy must rebuild these capabilities through growth-driving supply-side reforms and targeted demand-side interventions, underpinned by institutional reform.

- If successful, these measures will foster national champion companies in R&D-intensive and dual-use sectors, and attract FDI that builds strategic capabilities.

- This paper focuses on how the Government should deliver the demand-side interventions that have often been plagued by waste and jam-spreading in previous industrial strategies. Without clear prioritisation, the Government’s proposed broad sectoral approach risks repeating past mistakes.

- We argue for far greater rigour, precision, and expertise to be introduced to UK industrial policy. Interventions should be focused and tightly scoped. We propose a strategic framework to enable this.

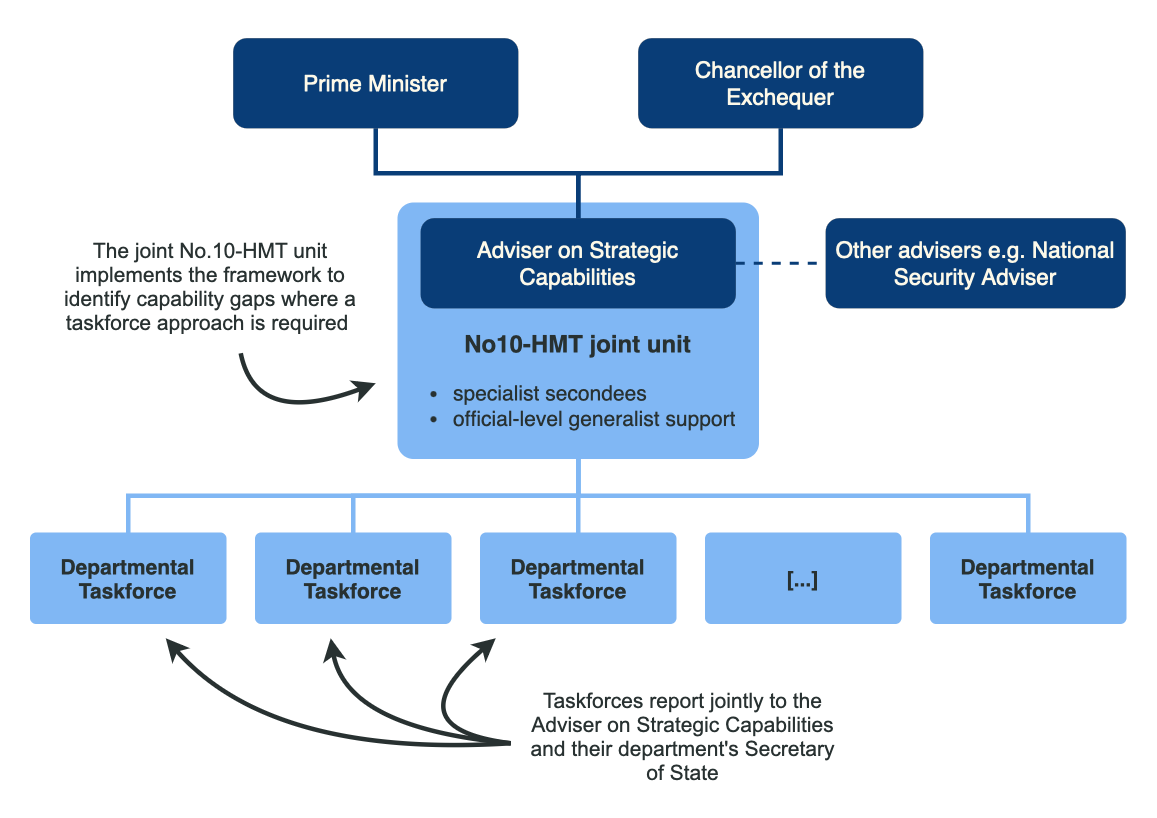

- To deliver the framework, a No.10-HMT unit should be created, led by a Prime Minister’s Adviser on Strategic Capabilities, with £8-9 billion of funding to be deployed on 4-6 strategic capabilities over the Parliament – aiming to develop UK leadership in strategically significant value-chains.

- A time-bound taskforce should be created for each capability area, led by an industry secondee with a track record of operational and entrepreneurial success. Both the unit and taskforces should be staffed with strong analytical capabilities and technical expertise drawn from the private sector, as well as experienced civil servants.

- Taskforces should have significant freedom and authority to use tools such as strategic procurement, grants, export finance, and advance market commitments.

- This approach concentrates effort where the UK can build leverage and restores the ability to act with speed and focus when it matters most.

Recommendations

- Growth and security: The Industrial Strategy should aim to drive growth through supply-side reforms and develop Britain’s strategic capabilities through demand-side interventions. It should be underpinned by substantial institutional reform.

- National champions and FDI: The Industrial Strategy should foster an environment in which national champion companies can emerge in R&D-intensive and dual-use domains. It should ensure Britain can attract productive Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) that creates new strategic capabilities.

- Delivery through taskforces: The Government should establish a new joint No.10-HMT unit to identify and build strategic capabilities. Led by a new Prime Minister’s Adviser on Strategic Capabilities, the unit will identify 4-6 capabilities for urgent action, and allocate an approximately £8-9 billion budget to departmental taskforces to deliver these over this Parliament. Taskforces would operate with significant delegated authority, run by external chairs, staffed from industry and government, and with clear accountability to the centre of government.

- Framework for interventions: Interventions to build strategic capabilities should follow our framework of: 1) identifying priority areas; 2) assessing current UK capacity; 3) selecting capabilities for intervention; 4) deploying the policy toolkit.

Introduction

The world is experiencing a period of colossal upheaval. The Information Age has brought us the internet, the fragmentation of media, and the AI revolution all in a few decades. Simultaneously, the rise of China, globalisation and the relative decline of traditional Western powers have upended geopolitics. In this environment, maintaining national agency requires more than smart diplomacy. To prosper, states need a set of core economic and technological capabilities that allow them to bargain with other countries, repel external threats, and manage complex global challenges.

Strategic advantage has always belonged to those with productive capacity. During WWII, Britain and the US repurposed their automotive industries to produce tanks and jet engines. During the pandemic, nations with domestic pharmaceutical capacity used it not just for health security, but also for geopolitical leverage. Today, OpenAI and Anthropic are working with Anduril and Palantir respectively to integrate their technologies into the US military.

These dynamics are increasingly central to modern statecraft as countries compete not only through diplomacy and military strength, but also by leveraging strategic relationships with firms. This development has been described as involving the securitisation of economic actors, as governments treat firms in AI, biotech, and semiconductors as strategic assets; the balkanisation of global systems, as supply chains fracture and technological standards diverge; and the weaponisation of interdependence, as firms act as conduits for strategic leverage.

This does not negate the continued importance of alliances, fiscal and monetary stability, or conventional defence posture, all of which remain essential to national sovereignty. But it does point to an important domain of statecraft in which economic and technological capabilities confer not just prosperity, but power.

Yet despite the importance of these capabilities, previous industrial strategies have failed to foster them. These strategies have been insufficiently focused - trying to achieve too many different objectives at once and spreading resources too thinly. Meanwhile, the institutional arrangements underpinning the strategies have militated against success by optimising for process and consensus rather than effective delivery.

The forthcoming Industrial Strategy must not fall into these traps and should see fostering Britain’s strategic capabilities as one of its core goals. Radical supply-side reform will be vital to this, and the strategy as a whole. This paper, however, centres on how government can deliver the demand-side interventions needed to build these capabilities.

First, we outline what the overall goals of the Industrial Strategy should be – providing a foundation for the Centre for British Progress’s future work on this topic. We then look specifically at how the UK can build strategic advantage. As this concept can often seem vague, we outline the ways in which strategic capabilities are leveraged by governments. We then offer an ambitious and dynamic institutional arrangement that will allow the Government to operate with the speed and personnel needed to foster these capabilities. Finally, the paper provides a detailed framework for how strategic capabilities can be identified and developed. We do not argue that our proposals should be the only interventions made under the Industrial Strategy, but they are critical to securing the UK's long-term security and prosperity.

Part 1: Where we are

Britain is not prepared for the upheaval of the 21st century

For several decades, Britain’s economic policy was oriented around the assumption that the world would become increasingly benign, and that openness alone would lead to prosperity. This assumption has proven to be false. From being western Europe’s worst-hit country in the energy shock of 2022, to seeing our ammunition stocks dwindle during the Russia-Ukraine war, Britain has allowed itself to become increasingly vulnerable. These disruptions have damaged us both economically and strategically.

Sovereignty is a cornerstone of politics in any era. It is not about nostalgia for imperialism, throwing aside existing strengths or retreating into autarchy. It is about having the national agency to respond to global events. Britain cannot outspend or outscale the great powers. Nor should it try to wall itself off from global markets or R&D networks. We must, however, actively build the capabilities that give us the ability to engage with the world, respond to shock events and safeguard our national security.

Britain’s deep economic problems

Britain’s economic underperformance is now too persistent to explain away as cyclical variation. For decades, the UK has had one of the lowest investment-to-GDP ratios in the G7 – a key reason why our productivity has flatlined over the last decade. The consequences are now being felt across society. Had the UK maintained its pre-2008 growth trajectory, the average household would be £7,000 better off.

Beneath Britain’s macroeconomic stagnation lies structural constraints that limit the country’s capacity to invest, produce, and adapt. The UK has the highest industrial electricity prices in the developed world. Our planning regime deters investment and slows infrastructure buildout. Judicial review routinely delays or deters construction. Industrial space near major cities is far more expensive, and lab space more scarce than in comparable economies. Regulation routinely slows deployment in sectors where timing matters. Grid and water infrastructure require urgent upgrades, while transport systems often fail to connect large parts of the country..

Meanwhile, the UK continues to train world-class researchers but we remain a net exporter of inventors, and our most talented individuals are leaving the country, rather than building careers or businesses in Britain. High-end technical talent is increasingly mobile, but is often deterred by our costly visa regime.

These systemic weaknesses make the UK less able to build, scale, or respond under pressure. Without a foundation of affordable energy and construction costs, and modernised infrastructure, Britain will struggle to develop the sovereign capabilities it needs.

Britain’s capability gaps

Beyond our weak supply-side foundations, Britain has significant institutional and capability gaps across the technology pipeline. Empirical data shows Britain's private R&D investment suffers from structural weaknesses: foreign-owned businesses now account for nearly half (48%) of total business R&D spending while only two of the world's top 100 R&D-investing firms are UK-headquartered. The UK's business R&D intensity, already trailing our peers, is now on a downward trajectory.

Our R&D base still contains globally prestigious institutions, but it has lost momentum. In AI, for example, without Google-owned DeepMind the UK’s share of top-tier citations falls from 7.84% to 1.86%. DeepMind succeeds in spite of the UK system, not because of it. The deeper problem is that we have not built the capacity to hold on to talent, scale new market entrants, or convert research into national strength.

UK universities, already in a deepening funding crisis, face growing competition from well-resourced corporate labs and more agile international research systems and institutions. Even where the UK produces excellent science, we lack sufficient translational infrastructure to move ideas from lab to market, especially in domains like advanced manufacturing, defence, and healthcare. As a result, our industrial R&D base is thinly spread, with few large R&D-intensive firms and little sectoral diversity.

Britain is also falling behind in its manufacturing and heavy industry. Robot installations significantly lag our competitors. The US and Korea are deploying robots at over 8x the speed of the UK – China over 70x faster. Moreover, the UK chemicals sector, which has historically been a strength, has seen output decline significantly since the pandemic.

An Industrial Strategy for strategic advantage

What we have described above are strategic capabilities. These are the technologies, goods, and industrial assets that, if controlled by or located in the UK, increase its national power and security, economic resilience, and leverage in crises. Some examples include: chemical processing, semiconductor design, robotics, cyber security, geospatial software, electron beam welding, and drug or drone manufacturing.

These capabilities exhibit many characteristics that align with core rationales for industrial policy. This includes, generating spillovers that cannot be fully captured by individual firms, requiring simultaneous investment in skills, infrastructure, and supply chains that cannot be coordinated by private actors alone, and being supported by public goods that are under-provided by markets.

Given their importance to national security, prosperity and resilience, fostering strategic capabilities should be a core objective of the Industrial Strategy.

Part 2: Where we need to get to

Foundations of industrial strategy

Recommendation 1: The Industrial Strategy should aim to drive growth through supply-side reforms and develop Britain’s strategic capabilities through demand-side interventions. It should be underpinned by substantial institutional reform.

Delivering growth and lasting resilience requires a radical shift in how the country approaches economic policy and institutional reform. To do this, the Industrial Strategy should operate within a three-part framework:

- Supply-side reform: Building the foundations for broad-based economic growth

High energy and land costs, and our significant barriers to construction, erode Britain’s competitiveness. They raise the cost of doing business, undermine the state’s ability to act, and reduce the feasibility of domestic manufacturing and innovation, even in areas of clear strategic value.

For an industrial strategy to be successful, supply-side reform must address the full range of obstacles that constrain Britain’s ability to build. The Government must drive down energy costs, cut restrictions on construction, rebuild our national transport infrastructure, and enable the data centre build-out needed for widespread AI deployment.

- Demand-side intervention: Developing strategic capabilities through industrial policy

Supply-side reforms alone will not deliver the capabilities that Britain needs to thrive in an unstable world. National efforts to build sovereign capabilities must be accelerated by the state taking an active role in shaping markets, concentrating demand, and accelerating deployment of technologies.

In addition to traditional policy levers like R&D grants or export finance, government should create predictable demand in advance and de-risk investment in strategically important areas.

- Institutional reform: Building the state capacity needed to execute industrial policy

Britain’s governing institutions suffer from a structural deficit of agency and a bias towards process over outcomes. Power is often dispersed and accountability is blurred. For too long, ineffective recruitment and management practices, deficits in expertise, and procedural bloat have gone unaddressed.

To execute an industrial strategy effectively, a government must be able to make judgements about technology, work closely with companies, and act decisively. Institutional structures must empower expertise, facilitate the development of clear priorities, and enable projects to be executed with a proportionate risk appetite.

Each of these elements matter to industrial policy, and the functioning of the state more generally, but they cannot all be addressed in a single paper. As such the remainder of this report focuses on one critical component: how government should be set up to deliver investments in strategic capabilities.

Dimensions of strategic leverage

Recommendation 2: The Industrial Strategy should foster an environment in which national champion companies can emerge in R&D-intensive and dual-use domains and ensure Britain can attract productive Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) that creates new strategic capabilities.

With a small internal market and limited natural resources, Britain cannot expect to indigenise entire supply chains. Instead, we will have to target niches where we can build strategic advantage. This means focusing on fostering firms, and building assets, that occupy critical positions in supply chains or provide capabilities that increase our national agency in a crisis, such as vaccine production.

The table below illustrates how particular strategic capabilities can be leveraged by states to support their interests. Some are available to the UK, while others are not. Certain mechanisms, especially export controls, are only effective in particular contexts or over limited time periods and can have unintended consequences.

Domain | Example | How domestic capability was used | Security dividend |

|---|---|---|---|

Economic statecraft and export controls | Roche (Swiss firm) reagents factory in Germany used as leverage in vaccine diplomacy during Covid-19 pandemic (2020) | The German government threatened to withhold access to this supply-chain chokepoint if the US executed its planned seizure of Moderna supplies. | The White House backed down and Europe was able to maintain access to vaccine supplies. |

International Transfer in Arms Regulation (ITAR) export restrictions on US night vision goggles (NVGs) (1990s-2020) | ITAR export-controls prevented other countries from accessing leading-edge NVGs. | For a period, the US held a significant battlefield advantage in night warfare. | |

Serum Institute of India temporarily halted exports of AstraZeneca vaccine (2021) | India paused exports of Covid-19 vaccines during the Delta wave. | This increased the number of vaccines that could be deployed in India during a period of high demand. | |

Emergency response | General Motors and Ventec ventilator production under US Defense Production Act (2020) | GM re-purposed an Indiana auto-parts plant in 14 days to mass-produce ventilators when supplies were low. | Rapidly filled an equipment gap at the peak of the pandemic. |

Ventilator Challenge UK coordinated by the High Value Manufacturing Catapult (2020) | The Consortium established seven new large-scale ventilator manufacturing facilities at existing industrial sites. | Delivered 13,437 ventilators to the NHS in response to the anticipated escalation in COVID19 cases. | |

Human capital & state capacity | UK Vaccine Taskforce (2020) | Embedded experienced industrial operators from domestic firms like GSK into key positions in the taskforce. | Industry experts negotiated more favourable contracts for the UK compared to the EU. The UK became one of the first countries to start a mass vaccination rollout. |

GM president Bill Knudsen brought into the US federal government in WWII (1940) | Knudsen coordinated the federal government and industry to put US manufacturing on a war footing. | US manufacturing capacity was converted to meet the needs of the DoD, which saw aircraft production treble between 1941-44. | |

SpaceX Demo-2 The first US crew launch since Shuttle era (2020) | Privately-developed spacecraft restored sovereign human-launch capability to the US. | Ended reliance on Russian space technology and embeds cutting-edge commercial engineers inside US space strategy. | |

Human capital & ecosystem reinvestment | Daniel Ek (Spotify) investing €100m into defence-tech startup Helsing (2021) | Wealth from a tech giant reinvested into capital-intensive deep-tech that VCs often avoid due to high barriers to entry. | Accelerated Europe’s sovereign defence-tech capabilities and signalled to other investors that new European defense companies can be created. |

Military surge production | Car manufacturers like Chrysler and Vauxhall converted factories to produce engines during WW2 (1939-45) | Existing automotive plants were repurposed and their workforce redeployed to meet wartime production needs. | Vauxhall produced over 7,500 Churchill tanks between 1941 and 1945. During the same period Chrysler manufactured over 25,000 tanks. |

Kaiser shipyards built Liberty & Victory ships during WW2 (1940-45) | Industrialist Henry Kaiser turned his construction knowledge to shipbuilding during WW2. | Large-scale ship building was crucial to allied naval efforts. Kaiser's ships were completed in two-thirds the time and a quarter the cost of other shipyards. | |

Dual-use tech transfer | Chrysler and General Motors’ expertise used to improve the M4 Sherman tank design and production (1942) | Civil-sector R&D, components and production methods repurposed for military systems. | Sherman tanks were able to be produced in vast quantities to serve the US war effort. |

OpenAI models integrated into Anduril defence systems (2024) | Civil-sector R&D and components repurposed for advanced military systems. | General-purpose AI is used to enhance the effectiveness of defence capabilities. |

With these dimensions of strategic leverage in mind, a successful Industrial Strategy will deliver two outcomes:

- National Champions: The emergence of large R&D-intensive and dual-use tech firms with the ability to anchor domestic capability and compete internationally.

- Productive FDI: FDI that creates new strategic capabilities on UK soil.

These should not be the metrics through which the success of Industrial Strategy is tracked; metrics should be much more fine-grained and specific to the strategic capability that the Government is seeking to develop. They are, however, the end products that we might expect if the strategy is effective.

National Champions

Large R&D-intensive and dual-use tech firms are vital to modern statecraft. Firm size and high R&D intensity typically correlate with faster technology diffusion, higher wages, and greater spillover benefits across local ecosystems. Larger firms also have higher rates of total factor productivity and productivity growth. They drive upskilling across the economy and generate intangible capital in the form of IP, data, and engineering know-how. Finally, evidence at the firm and aggregate level shows that multinational companies tend to concentrate their R&D spending in their home countries.

These patterns create a flywheel in which superstar firms succeed in global markets, generate liquidity and know-how, and reinvest them in domestic strategic industries that traditional finance might be reluctant to support.

The value of such firms cannot be measured solely in their contribution to GDP. These companies represent embedded assets that bolster national agency and crisis preparedness, and enhance their country’s role in international affairs. By creating cutting-edge products, these firms can help embed national standards in world markets and give their home states greater influence in trade negotiations and technology governance.

Finally, the founders and executives at these firms provide a vital source of human capital at crucial moments. From the US War Production Board using the country’s top industrialists to inform the war economy to Ian Hogarth being appointed the Chair of Foundation Model Taskforce, having successful entrepreneurs who understand technology and are invested in the fate of the country can significantly boost state capacity.

Productive FDI

Britain should not lose sight of the importance of FDI as it pushes to restore national capabilities. While sovereign ownership is important for some capabilities, FDI, in addition to its productivity benefits, can be an effective way to access resources, skills and know-how that the country would otherwise lack, especially in high-tech sectors. The Government should prioritise attracting investments that develop new strategic capabilities on-shore, provided they comply with national security requirements, and not conflate this with FDI that just transfers ownership of existing capital to foreign investors. For instance, the US CHIPS Act’s incentives successfully drew TSMC’s state-of-the-art fabs to Arizona, which strengthened American semiconductor access and brought crucial chip-manufacturing skills to the US.

A compelling example of foreign investment being leveraged for strategic advantage came during the Covid-19 pandemic. Germany was able to deter the US government from seizing key vaccine supplies by threatening to cut off access to vital reagents produced at a plant in Germany by Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche.

Part 3: How we get there

Industrial policy is vulnerable to familiar policy failure modes, the most common being the Government trying to do too much at once. When limited fiscal resources are diluted across numerous, loosely defined objectives, the result is jam-spreading: subscale interventions that lack the focus needed to have meaningful impact. This is often compounded by 'process capture', where interventions become trapped in bureaucratic systems that prioritise caution and consensus rather than meaningful outcomes. As a result, execution stalls, responsibility blurs, and the original purpose is gradually displaced by the process itself.

One of the most prominent industrial strategy programmes of the last decade illustrates the risks of business-as-usual structures even when the policy intent is clear. The Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund (ISCF) was intended to deliver mission-led R&D through high-agency, DARPA-style programmes. It instead became mired in administrative delay. According to the National Audit Office, it took up to 72 weeks to approve challenges in Wave 3, in part due to the time required to develop business cases and navigate cross-government sign-off processes. UKRI’s own evaluation also pointed to coordination and governance challenges during the Fund’s early years.

The lesson is that when ownership is dispersed and delivery depends on interdepartmental consensus, even well-intentioned programmes fail. Without clear accountability, delegated authority, and greater risk appetite on spending and hiring rules, the current industrial strategy will lack the focus necessary to succeed and will likely follow a similar fate to the ISCF.

A different institutional approach is required, concentrating authority and shielding delivery from unnecessary bureaucracy to facilitate focused and decisive action. This must involve recruiting the expertise and skills needed to move from examining broad sectors to the detailed value chain analysis that is required for effective industrial policy.

Institutional delivery

Recommendation 3: The Government should establish a new joint No.10-HMT unit to identify and build strategic capabilities. Led by a new Prime Minister’s Adviser on Strategic Capabilities, the unit will identify 4-6 capabilities for urgent action, and allocate an approximately £8-9 billion budget to departmental taskforces to deliver these over this Parliament. Taskforces would operate with significant delegated authority, run by external chairs, staffed from industry and government, and with clear accountability to the centre of government.

High-agency taskforces with delegated authority

Create a dedicated No.10-HMT unit to establish and drive priorities

A dedicated joint No.10-HMT unit should identify 4-6 areas of capability that the Government should focus on, then assign responsibility and funding to departmental taskforces for scoping and delivering interventions in those areas. We describe these institutional arrangements here and set out a framework for identifying strategic capabilities in the subsequent section.

The unit should be led by a full-time Director General-level secondee from the private sector, appointed by the PM to be his Adviser on Strategic Capabilities (ASC), who is accountable for the taskforces’ delivery of demand-side interventions. The ASC must have strong operational skills, combined with deep industrial and entrepreneurial experience. The role should carry significant political weight, with direct support from both the Prime Minister, the Chancellor, and their senior political advisers.

External expertise should be brought into the unit on ‘tours of duty’ – time-limited postings in domains like AI, biotech, venture capital and industrial and financial analysis. To ensure that the unit can attract top industry talent, HMT should seek approval from the Civil Service Commission to increase secondees’ salaries on top of the civil service pay scales. Secondees should be supported by generalist officials, including those with high-side security clearance, who will provide institutional networks and experience of operating in government. This follows a similar model to the Vaccine Taskforce and Foundation Model Taskforce.

When the No.10-HMT unit is announced, it should have its budget pre-agreed for use during the Parliament, to be split between each departmental taskforce. We propose an initial headline commitment of approximately £8-9 billion. This figure aims to balance ambition and the UK’s fiscal constraints, and reflects the fact that not all innovation or industrial strategy funding will come from this budget. It is a midpoint between previous UK initiatives such as ISCF (£3 billion over eight years), and broader and larger-scale industrial strategies of other nations such as Korea (c.£25 billion over five years) and France (£20+ billion for innovation via France 2030). Making a substantial funding commitment prior to the ASC being appointed will help attract a top talent and signal long-term seriousness for hires in the founding team.

At the beginning of the strategy-setting process, we strongly recommend that the ASC, and the unit more generally, create close working relationships with all the relevant national security-relevant agencies and advisory bodies like the Industrial Strategy Advisory Council. This will help to draw on their existing analysis of capability gaps and build their support for the taskforces.

Establish a departmental taskforce for each priority area

For each of the 4-6 areas of strategic capability identified by the unit, the responsible government department should rapidly establish a taskforce to identify and deliver the targeted interventions needed to build UK capabilities. The No.10-HMT unit will then allocate a budget to each taskforce from the total funding pot.

Each taskforce should be embedded within an appropriate lead department, but operate with a high degree of autonomy. It should report jointly to the ASC and its Secretary of State, and have a clear mandate to design and deliver interventions that build national capability. While hosted in departments, taskforces should operate outside standard governance groups or cross-Whitehall mission boards, preserving their ability to act with focus and speed.

Each taskforce must be led by an expert chair, appointed by the ASC in consultation with the relevant Secretary of State. Every Chair should have extensive, relevant industry experience, a strong record of operational delivery, including an ability to move quickly and take bold action, and sufficient bandwidth for the role.

Each taskforce should contain a mix of skills appropriate to the capability it is delivering, drawn from the public and private sectors. This is likely to include strong analytical capabilities (drawn in part from No.10 Innovation Fellows), technical and subject matter expertise, and experience from domains like finance and venture capital. These secondees will be critical to the success of this model. They are essential to ensuring that the taskforces can make informed decisions about complex and highly technical fields. They should be combined with existing civil servants who possess strong policy and operational skills, and the nous to navigate Whitehall.

After the taskforces have been established, the ASC could choose to downsize the joint No.10-HMT unit to reflect the fact that the initial strategy-setting and spending decisions are complete, but a core team will need to be retained to support the taskforces. Each taskforce should be responsible for building strategic capability by the end of the Parliament, at which point it will be closed, along with the No.10-HMT unit.

Each taskforce should be empowered to act quickly and ambitiously

Each taskforce should have a single business case for all spending under their remit, to be approved by the No.10-HMT unit. To enable the taskforces to act quickly and decisively, it is essential that each funding decision taken by a taskforce should not require additional business case clearance. Delegated limits should be applied within each taskforce’s budget; spending above these limits must be approved by the ASC and relevant Secretary of State.

The joint unit and ASC should set headline outcomes for each taskforce and then the taskforces should evaluate their progress towards delivering those outcomes.

The taskforce chairs should use their budget to direct departmental resources, using budget cover transfers to facilitate cross-departmental work and covering the costs of seconding staff from other departments, where this eases cross-Whitehall working. It is the ASC’s role to provide the necessary political backing, via the Prime Minister, to ensure this action is prioritised. Legislative changes are not necessary to use this model and would simply cause delays. The authority of the ASC and No.10-HMT unit must be used to drive increased delivery speed and risk appetite within existing processes.

Each taskforce should choose the policy levers that will most effectively tackle the problems that they identify. Specifically, taskforces should have the authority to:

- Implement non-standard instruments such as advance market commitments

- Direct their host department to launch rapid procurement projects

- Provide grant funding to teams, projects or individuals in the UK

- Provide firms with export finance

- Appoint programme directors with delegated budgets

- Establish new institutional vehicles for delivery

- Commission analysis and advice from departments and external bodies

This approach requires sustained political backing, strong leadership, and a tolerance for variance in approach. Strategic capability cannot be delivered through fragmented accountability and process-heavy systems. It requires concentrated authority, insulation from institutional inertia, and a mandate to act with urgency. A dedicated, empowered unit – backed at the highest political level – offers the clearest path to meaningful delivery.

From strategy to action: a framework for capability building

Recommendation 4: Interventions to build strategic capabilities should follow our framework of: 1) identifying priority areas; 2) assessing current UK capacity; 3) selecting capabilities for intervention; 4) deploying the policy toolkit.

The unit and taskforces are designed to act decisively, but their success depends on having a clear method for deciding what to do.

Too often government action gets bogged down in sectoral abstractions or inherited funding pipelines. Ministers and officials need a way to cut through these distractions. The Industrial Strategy must use an implementation framework grounded in a rigorous assessment of the UK’s needs and attributes, precise choices, targeted interventions, and honest trade-offs. The framework we set out below provides that.

Why the Government needs a better framework

Past efforts have fallen short. The previous government’s Own-Collaborate-Access approach to critical technologies was a step forward in principle, but did not provide the necessary granularity to identify which elements of the technology value chain should be targeted to meet the UK’s needs. As such, it did little to help ministers and officials navigate difficult resource trade-offs.

Similarly, the Invest 2035 green paper proposed eight growth sectors, but offered no method for prioritising within or between them. Its sectoral definitions – “digital and technology”, “financial services” or “creative industries” – are not used consistently in government and do not correspond neatly to industrial systems in the real world.

A purely sectoral approach militates against strategic prioritisation. It risks absorbing existing funding streams and lobbying priorities without evaluating their strategic value to the UK.

Strategic value cannot be inferred from sector identity alone. What matters is whether a specific policy in a defined area builds national capability that justifies the cost of intervention. Interventions that seek vague or generalised sectoral growth will likely fail this test. As such, the Government will struggle to make informed decisions about resource allocation in the strategy. If this is not addressed, the strategy risks becoming a loose collection of shallow interventions.

Our four-part framework offers a path out of this. We focus on having specific objectives and targeting market failures, rather than sector identity. This involves:

- Identifying strategic capabilities

- Assessing current UK capacity

- Selecting capabilities and costing interventions

- Deploying the policy toolkit

This framework is not a substitute for judgement. Many important choices will still depend on the discernment of capable people. But in a system that too often defaults to inertia and compromise, our framework offers a disciplined way to focus attention, test assumptions, and avoid strategy-making that is merely for show.

The framework should also not impose unnecessary process, slow down budget allocation, or delay urgent action. In some cases, particularly where capabilities are already well understood, steps may be accelerated. The purpose is to guide strategic focus.

Step 1: Identifying strategic capabilities

The first task for the unit is to identify the capabilities that matter most for national power, resilience and freedom of action.

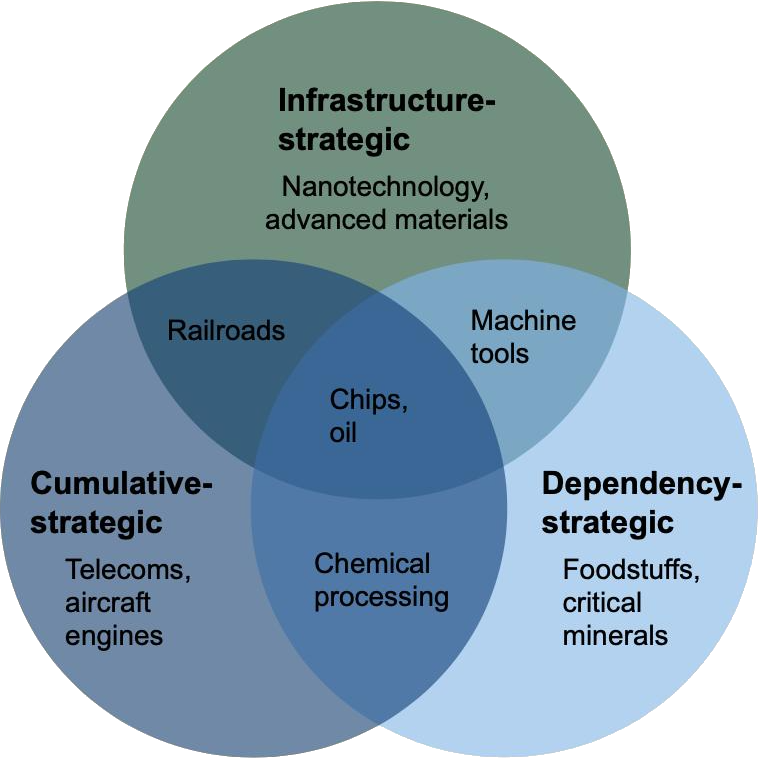

To bring greater discipline to this question, we draw on Ding and Dafoe’s, The Logic of Strategic Assets, which has been used by the OECD and others. It identifies three characteristics of strategic capabilities, providing a structured way to assess the need for targeted public investment.

Below is an outline of each characteristic, and some questions that can help identify whether particular capabilities fit into them:

- Cumulative-Strategic: Capabilities characterised by strong cumulative advantages (learning-curve effects, first-mover advantages, network effects, economies of scale) that create high barriers to entry. The jet engine industry is an example; enormous R&D costs and learning-by-doing mean that even with significant investment, new entrants struggle to catch up.

- Does unit cost or performance improve markedly as cumulative production or deployed data increase?

- Would early entrants enjoy durable cost, data, or brand advantages that later firms would struggle to surmount?

- Do users, suppliers, or complementary innovators become more valuable as adoption grows, reinforcing the early leader?

- Are the upfront R&D or plant-building costs so high, and pay-offs so uncertain, that private firms are likely to under-invest without policy support?

- Infrastructure-Strategic: Capabilities that serve as general-purpose infrastructure for the broader economy or military that generates diffuse positive spillovers. These are often foundational innovations that enable downstream advances across multiple sectors. Historical examples include railroads in the 19th century and electric power grids or radar in the 20th century.

- Does the capability or technology enable productivity gains or innovation across many unrelated sectors?

- Are most benefits external to the firm that bears the cost, making it hard to fully recoup the investment privately?

- Would widespread economic or defence capabilities stall if this technology lagged or failed?

- Does effective deployment require network build-out, standard-setting, or large-scale coordination?

- Dependency-Strategic: Capabilities where supply is highly concentrated or subject to external control, making a nation vulnerable to cutoff or manipulation. Here, the externality is a security externality of supply risk in a rivalrous world. If a critical input, for example, GPU manufacturing, is supplied by only one or few countries, states may intervene to reduce dependency.

- Is the resource dominated by a handful of foreign firms or countries?

- Could an adversary disrupt, embargo, or manipulate supply?

- Are viable substitutes scarce, technically inferior, time-consuming, or prohibitively expensive to develop?

- Would loss of access seriously impede core economic activity, public welfare, or national-security missions?

- Does dependency grant the supplier coercive power in diplomacy, trade, or conflict?

Step 2: Assessing current UK capacity

To make investment decisions in relation to strategic capabilities, the Government needs to understand where the UK currently has strengths and weaknesses. This understanding will inform where capabilities should be built on, where there are gaps or dependencies, and where investments might be wasted, for example where the UK lacks the human capital to develop a given capability.

As such, a rapid security and preparedness audit should be undertaken to provide a baseline understanding of all the UK’s strategic capabilities. This should involve mapping the UK’s domestic capabilities and dependencies, with a view to optimising the security dividend from investments.

The following questions should be considered for each capability:

- How many UK firms operate in this area? What is their position in the market?

- How much human capital is in the UK working in this area?

- What critical physical assets are in the UK?

- How elastic is demand in different crisis or emergency scenarios?

- How acute are dependencies? How severe would bottlenecks or withdrawal of supply be?

- How likely is disruption and when is it likely to occur?

- How much existing leverage does the UK have to ensure access to the particular capability?

- How much does it cost to develop capabilities? How readily available are the relevant levers? How much does the state risk distorting markets by doing so?

Step 3: Selecting capabilities and costing interventions

Having mapped the UK’s capability needs and capacity gaps, the Government will need to identify where to target interventions. This should be based on the following principles:

- Focus on market failures: Intervene only where addressable market failures are large (relative to the cost of intervention). This can be informed by the formula below. This does not mean that the Government should wait for failures to arise in areas of critical importance. Indeed, we anticipate the Government would regularly and proactively promote future industries using this framework prior to market failures arrising.

- Targeted capability building: Every intervention should directly link building a specific capability to a clearly defined advantage for the UK.

- Primary objectives: Any intervention made through the Industrial Strategy should, as far as possible, focus on a particular policy goal (e.g. increasing national security by building drone production capacity).

Decisions about interventions should be informed by the potential benefit to the UK from addressing the current or future market failure, relative to the cost of intervention. This can be understood by calculating the total addressable market failure (TAMF). This is a product of three things: the importance of the capability, the size of the externality, and the ability of the UK to capture the benefits of any investment in the capability.

TAMF = Importance × Size of externality × UK appropriability

A potential measure of “Importance” is the size of the market or, where a capability is a key component of a wider value chain, the market size of the downstream industries. Alternative measures include its potential impact on national security, or societal or political objectives.

The “size of externality” refers to the magnitude of spillovers, which would be proportional to the capability’s importance or size of the market.

Finally, “UK appropriability” is the proportion of the externality that accrues to the UK. This includes how feasible it is to develop strategic advantage in an area, based on how close the UK is to technological frontier and our domestic companies, supply chains and workforce. It should also include the degree to which the UK specifically is well-placed to leverage access to the capability, or whether externalities from investments would accrue significantly more to the UK than to other countries. For example, with under 5% of European steel production, greening steel is probably not a problem that the UK should devote significant resources to addressing, since the vast majority of spillovers would be captured by international competitors.

It is necessary to multiply these factors to set a relatively high bar for action. For example, if a capability has high importance and large externalities but is not appropriable by the UK, it does not merit intervention.

These are not always quantifiable but can be a helpful qualitative screening tool and lens to understand which interventions are suitable for the industrial strategy as the table below sets out:

Market size | Size of externality | UK appropriability | Overall value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Advanced semiconductor manufacturing | High | High | Very low | Low |

AI in drug discovery | High | Medium | Medium | Medium |

General-purpose robotics | High | High | Medium | High |

The fact that there is a large total addressable market failure does not mean that an intervention is justified. For example, an intervention could be very expensive, or it could have harmful secondary consequences, such as chilling the market. These costs, including any deadweight or social costs from taxes imposed to provide funding for the intervention, could outweigh the benefits of correcting the market failure.

Step 4: Deploying the policy toolkit

The final stage is effective execution. Once strategic capabilities have been identified, assessed, and selected for intervention, the Government must act with focus and speed. In addition to the institutional arrangements described above, this requires a delivery toolkit that combines funding, procurement, regulatory, and institutional levers to stimulate capability-building at pace.

Principles for targeted execution

Effective delivery demands focused mechanisms, proportionate to the level of uncertainty and strategic value involved. The following principles should guide how the toolkit is deployed across different capabilities:

- Match instruments to the problem: Execution should draw on a range of demand-side tools such as grants, procurement or advance market commitments, each selected to fit the needs and opportunities of capability-building. Where speed and judgement are essential, funding should flow through empowered programme leads with the authority to select teams, stage-gate progress, and reallocate capital flexibly.

- Prioritise feedback and evaluation: All interventions should include defined go/no-go criteria set at the outset. These should test, at pre-defined milestones, whether the solution is technically effective, scalable, and operationally viable, allowing the Government to adjust course rapidly and avoid sunk costs.

- Concentrate for impact: Spreading investment thinly across sectors or regions in pursuit of ‘balance’ risks diluting strategic intent. Where an intervention is considered justifiable, it should remain tightly focused and, where merited, large investments should not be avoided.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following for generously providing their input and insights: Henry Palmer, Giles Wilkes, Diane Coyle, Nitarshan Rajkumar, John Myers, Jack Wiseman, Pedro Serôdio, Alex Chalmers, Helen Ewles, David Sweeney, Anastasia Bektimirova, Jonno Evans, and Laura Ryan. All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]