Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Context

- 3. System failure: why UK defence tech stalls

- 4. The solution: a high-agency, expert-led innovation engine

- 5. Plan of Action

- 6. Budget

- 7. Authors

- 8. Acknowledgements

Summary

- The UK Government has announced £400m for UK Defence Innovation (UKDI), a new unit to equip our Armed Forces with cutting-edge technology and grow high-tech businesses in the UK’s defence ecosystem. This paper sets out how to make that ambition a reality.

- The UK faces escalating threats and increasing geopolitical uncertainty. Sovereign defence capabilities must be developed at unprecedented speed. But the UK’s defence innovation system is too slow and risk-averse to respond effectively.

- Despite strong research and increasing investment, the UK is held back by institutional inertia, poor translation of operational needs into commercial activity, and a lack of mechanisms to bring new technologies into use. Without urgent action, the country risks falling behind, and losing the ability to act decisively and independently in future conflicts.

- The launch of UKDI offers a clear opportunity to change course – but only if the Government is prepared to be bold. Drawing on lessons from DARPA (autonomy), the US Strategic Capabilities Office (speed of deployment), and the UK’s Vaccines Taskforce (bureaucratic bypass and mission focus), UKDI can address long-standing structural weaknesses in the defence innovation system.

- UKDI should be built around expert Technical Directors with the autonomy, flexibility and freedom to run high-impact, high-speed programmes. Rather than simply funding research, the focus must be on mission-driven execution, rapid decision-making, and direct engagement with industry to accelerate the adoption of critical technologies.

- This is not a proposal for broad reform. UKDI is a focussed intervention aimed at overcoming specific system failures and showing what a different model can achieve. Done right, it will not only strengthen sovereign defence capabilities, but also stimulate growth in dual-use technologies and anchor critical parts of the UK’s industrial base.

- While UKDI may eventually become an arm’s-length body, it should initially be set up as a Task Force within the Ministry of Defence to minimise setup time. The task force should have a Chair, with senior-level industrial defence experience, reporting directly to the Prime Minister and Defence Secretary.

Context

The UK faces escalating geopolitical uncertainty, marked by rapid technological change and the emergence of new forms of warfare. Advances in AI, autonomy, and cyber capabilities are reshaping the character of conflict, and turning domains such as space into increasingly contested arenas. Rapid deployment of advanced capabilities can be decisive, and future conflicts will be won by those who can innovate and integrate at speed. Our traditional research and development (R&D) and procurement systems are not built for this environment.

Technological leadership is a critical part of national security. The war in Ukraine has demonstrated how autonomy, battlefield adaptation, and AI-enabled systems (from automated reconnaissance drones to real-time targeting tools) can provide a tactical edge. Meanwhile, US policy shifts may limit our access to key technologies, making sovereign capability more urgent. While alliances such as NATO, AUKUS, and Five Eyes remain vital, the current environment shows that meaningful collaboration depends on sovereign capability. The ability to develop, adapt, and deploy critical technologies at speed is now the price of admission to serious strategic partnerships.

This is also an economic opportunity. Strategic competitors deliberately use defence demand to drive growth, activate domestic supply chains and seed frontier industries. For example, China has explicitly integrated military-civil fusion (MCF) into its national development strategy, using defence procurement to grow domestic AI, aerospace, and quantum sectors, often accelerating capabilities with both military and commercial relevance. And the United States has long used defence procurement as an industrial policy tool, from the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA)'s foundational role in the tech sector, to recent CHIPS Act provisions linking semiconductor investment to national security goals.

The UK, by contrast, too often separates innovation policy from national security needs. As a result, promising dual-use technologies stall or are commercialised overseas. A stronger, mission-driven defence-industrial base would not only enhance our resilience to economic shocks but also drive growth in key sectors such as AI and advanced manufacturing.

The UK has taken important steps, recognising defence as a priority sector in the Industrial Strategy and establishing the role of National Armaments Director to drive exports and supply chain resilience. But, without a dedicated innovation mechanism that turns defence needs into industrial opportunities, this momentum will not deliver strategic or economic advantage at pace.

System failure: why UK defence tech stalls

Despite world-class research and substantial investment, the UK faces a core strategic failure: getting critical defence technologies from the lab to the front line. This failure has real operational consequences: when promising capabilities stall in development or languish in procurement pipelines, operational advantage is lost, and with it, the ability to deter or respond decisively in conflict.

This failure is not technological. A web of institutional, cultural, and economic barriers slows progress, dilutes focus, and wastes potential. UKDI cannot be expected to solve all of these problems, but unless it is explicitly designed to overcome or bypass them, it risks becoming part of the problem. We set out these barriers below.

The lab-to-field gap

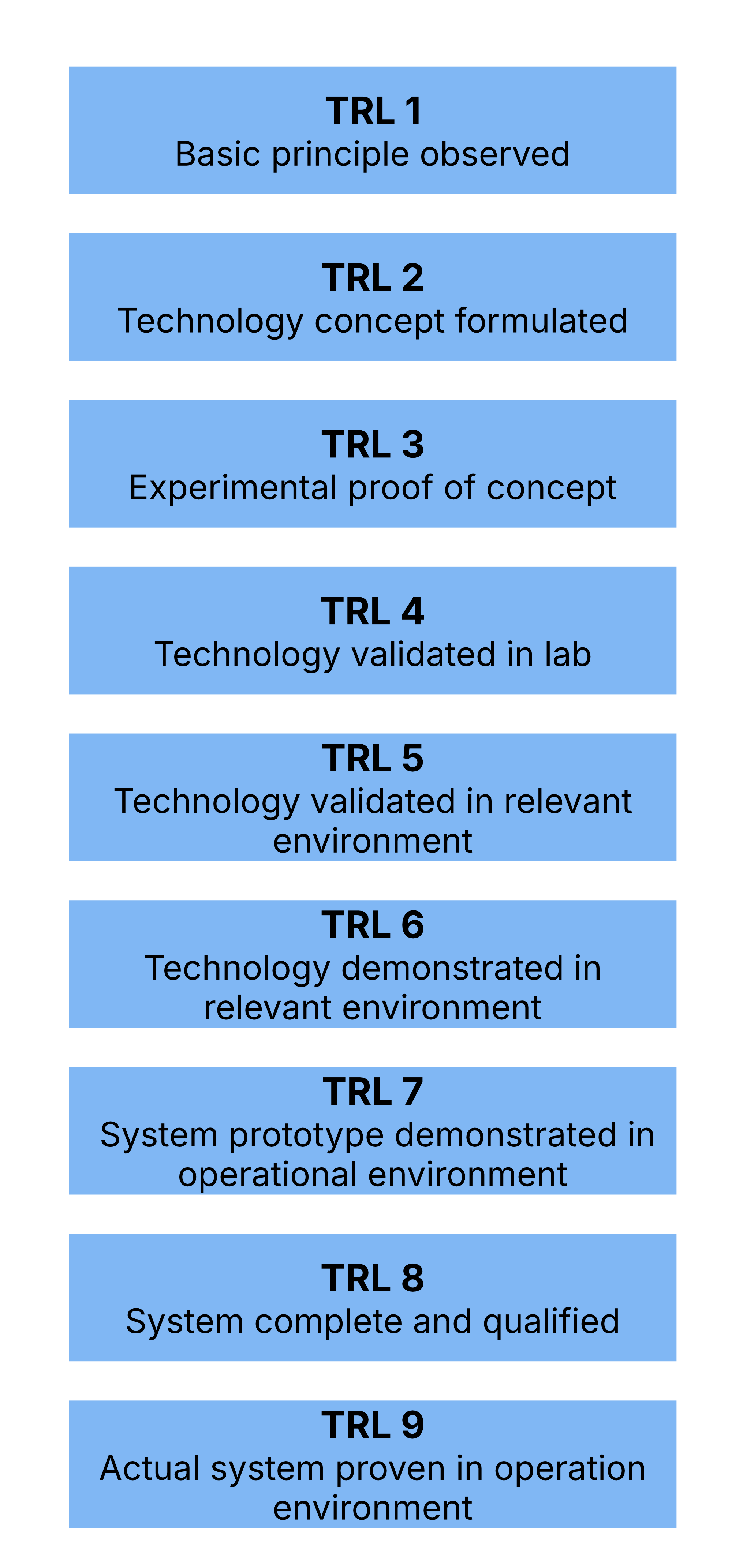

The UK faces significant challenges in bringing homegrown defence technologies to operational scale. Technologies developed to Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 2-4, often within academia or national labs, fail to transition because the UK lacks dedicated mechanisms for mid-to-late-stage defence technology acceleration. The UK’s defence procurement system is optimised for established, large-scale programmes rather than integration of novel technologies.

Even when technologies have matured, they face significant hurdles in being incorporated into existing platforms or programmes. The investment needed to integrate them, adapt to platform constraints, and meet certification requirements is consistently underestimated and underfunded. Furthermore, budget cycles, requirements processes, and programme timelines are too slow and rigid to accommodate the rapid pace of technological development. As a result, developed technologies often miss their window for integration into existing programmes.

And when technologies are fully proven, they still face "last-mile" barriers. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) and its prime contractors tend to be risk-averse in adopting technologies before they have been extensively tested in operational environments. Warfighter sponsorship – senior military leaders who actively back and advocate for a new technology – is often essential to close the gap, but in the UK such sponsorship is fragile and inconsistent. Success often hinges on individual service sponsors whose interest and continuity cannot be guaranteed. As a result, promising technologies can stall when champions move on or institutional priorities shift.

The US Department of Defense created organisations like the Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO) because it recognised the challenges of transitioning technologies at later stages of development into operational use. The UK faces similar challenges but lacks equivalent mechanisms.

Case Study: The SULSA UAV – a 3D-Printed Opportunity Missed

In 2015–16, the Royal Navy trialled the University of Southampton’s SULSA – the world’s first fully 3D-printed aircraft – launching it from HMS Mersey and later from an Antarctic icebreaker. The UAV demonstrated TRL 6–7 performance in maritime conditions and showed promise for shipborne intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. But progress depended on one-off interventions from senior figures in the Royal Navy, not institutional support. There was no mechanism to adapt the prototype, align it to a formal requirement, or fund integration. SULSA illustrates a system that can spark innovation, but lacks the structure to turn it into sovereign capability.

Classified needs, no commercial signal

The UK lacks a structured mechanism to translate classified operational needs into clear, commercially actionable problem statements. As a result, critical defence requirements often fail to generate focussed R&D or activate the UK supply chain, leaving capability gaps unaddressed. This is compounded by MOD procurement having no incentive to favour domestic firms; even when needs have been identified, there is no built-in mechanism to channel investment into the UK defence-industrial base.

This gap is often papered over by presenting foreign-owned firms with UK subsidiaries – such as Leonardo or Anduril – as domestic champions. While these firms play important roles, equating foreign ownership with sovereign capability risks obscuring the distinction between local employment and national industrial resilience. It is fundamentally incoherent to pursue industrial strategy while allowing defence procurement to remain structurally indifferent to domestic capacity.

At root, the problem is a disconnect between classified requirements and the commercial landscape. Defence primes, SMEs, and startups often cannot engage because operational needs are not translated into commercially viable problem statements. Without a clear signal of demand, firms have no basis to invest – weakening industrial responsiveness and slowing innovation across the ecosystem. This also undermines UK competitiveness: firms that might otherwise scale dual-use technologies or anchor new supply chains are left without a route to market.

These barriers are compounded by slow and opaque security clearance processes, which limit participation by non-traditional suppliers and prevent agile engagement with classified challenges. In the absence of more inclusive, enduring mechanisms, the system relies on stop-gap tools like Urgent Operational Requirements (UORs) – effective in a crisis, but too narrow and reactive to build long-term resilience in the defence-industrial base.

A system built to slow things down

The UK’s defence innovation system is held back by institutional drag. MOD procurement timelines can be measured in decades, not years – running at a far slower tempo than the pace of technological change. Acquisition decisions are made through risk-averse processes that prioritise strict financial, legal, and bureaucratic compliance over mission outcomes, with existing innovation systems largely benefiting incumbents. A 2020 NAO report concluded that current acquisition processes are no longer fit for purpose – and even the MOD acknowledges the need to prioritise “timely delivery over perfection.”

The upshot is that promising technologies stall long before they reach the front line. Other countries have introduced new contracting models, such as the US’s Other Transaction Authorities, to bypass bottlenecks, drive up commercial participation, and increase innovation. But the UK has yet to build a credible alternative pathway. The UK needs a defence innovation model that is faster, bolder, more decisive, and more in tune with technological opportunities across the innovation ecosystem.

No one is choosing where the UK should lead

Maintaining a technological edge depends on the ability to focus. But the UK lacks a structured process to identify and back high-priority sovereign capabilities – such as AI for decision dominance, electronic warfare, or advanced materials. Prioritisation exercises either have been too diffuse, leading to scattered and low-impact interventions, or they have been too unambitious, failing to capture technological opportunities at the edge of the art. In a resource-constrained environment, failing to choose is choosing to fall behind.

Without a plan for connecting our innovation strengths to our defence needs, the UK risks wasting its investments. While the MOD has the information and expertise needed to develop military technology, it lacks a pathway to act decisively. The Strategic Defence Review ought to provide the Armed Forces with overall clarity of purpose – but, in order to determine where the UK should lead versus where it should integrate with allies, we must do things differently.

Underused talent, outdated structures

Globally leading technology organisations have transformed how they approach R&D. Influenced by models such as DARPA and the culture of Silicon Valley, they have replaced process-heavy bureaucracy with judgement-led decisions centred around small teams of exceptional talent. Organisations like SpaceX, OpenAI, and DeepMind have shown that coupling top technical talent with strategic autonomy can deliver breakthrough innovation at speed – often outperforming much larger and more traditional counterparts.

This approach gives significant freedom to top technical leaders who combine subject matter expertise with execution capability. The model is not just for startups: we have seen it work within the UK government too. The Vaccines Taskforce, NHS Digital, and the Met Office’s weather modelling teams delivered rapid, high-impact outcomes by empowering technically skilled people to lead, and freeing them from conventional procurement cycles.

Defence innovation remains an outlier. It is still structured around compliance rather than results, with decisions made by committee and promotions tied to time in role rather than impact. This leaves much of the UK’s world-class technical talent sidelined or underutilised – while our competitors are building innovation models designed to attract and deploy such talent effectively.

These barriers are not just unfortunate – they are avoidable. Technologies fail to reach the front line not because they are unworkable, but because the system around them cannot move at the right tempo, translate need into demand, or empower the people who could deliver. Rather than attempt wholesale reform, the Government now has the opportunity to build a focussed, high-agency unit that bypasses these structural obstacles and sets a new standard for what effective defence innovation could look like.

The solution: a high-agency, expert-led innovation engine

The Government has taken an important first step in its commitment to establishing UKDI to accelerate the military’s technological edge through government–industry collaboration. But without an empowered team of exceptional calibre and a radically different approach, it risks becoming another bureaucratic layer rather than a catalyst for innovation. UKDI’s success depends on mission urgency, exceptional talent, and the pursuit of technological superiority.

To meet that challenge, the Government should establish UKDI as a highly autonomous innovation engine within the MOD, built from the outset around top talent, streamlined processes, and a high level of political cover. Its role will be to translate classified military capability gaps and industrial assessments into clear technology problem statements, and to break these down into fundable, industry-executable programmes with ruthless go/no-go stage-gating.

UKDI should focus its efforts where innovation adds unique strategic value – avoiding duplication with commercially available solutions, and actively seeking opportunities to co-invest in dual-use technologies with commercial potential. This means concentrating on capability gaps where speed, sovereignty, or integration are decisive – not on broad-based innovation or early-stage research, which are already well served by other mechanisms.

UKDI isn’t designed to fix every part of the defence innovation system, and it shouldn’t try to. But by tackling a specific set of high-friction problems with a different model, it can create a new pathway for getting critical technologies into use. In doing so, it has the potential to unlock progress elsewhere, by showing what can work even within the system as it stands.

Likewise, UKDI will not fix procurement, but it can model how procurement could be fixed – by demonstrating the benefits of speed, accountability, and technical leadership in a live operational context. UKDI can act as a procurement sandbox: an operational test-bed for new technologies, new suppliers, and new commercial models. Its aim should be to accelerate specific technologies from TRL 4 to 7+, and to expedite their handoff to procurement or operational deployment, in turn activating domestic industrial capability and anchoring critical supply chains.

The Technical Director Model

UKDI should be built around empowered, top-tier technical leaders with direct authority over ambitious funding programmes. Unlike traditional Whitehall structures, UKDI Technical Directors will be technical experts with excellent leadership capability and the operational freedom needed to run a coordinated R&D programme – not generalist civil servants or rotational appointments. An explicit goal is to emulate the operational successes of the US SCO model and the UK Vaccines Taskforce, where highly agentic, expert individuals are provided with sufficient resources and cover to drive success.

UKDI should focus tightly on attracting top talent, drawing lessons from organisations like Google DeepMind and SpaceX, where high-impact innovation stems from concentrated technical excellence, clear mission focus, and empowered leadership. That means building an environment where exceptional individuals have the autonomy, resources, and mandate to deliver, rather than being constrained by traditional bureaucratic norms. (See Annex A for further examples)

To attract exceptional leaders, UKDI should be given extraordinary pay flexibilities, following the AI Security Institute (AISI) model, which supplements the standard salary caps with generous technical allowances (at 1-2x base). Technical Directors would have fixed-term "tours of duty" (3-4 years) to maintain fresh thinking and urgency while being additive to their careers. To ensure multidisciplinary strength in depth, talent should be sourced from across multiple domains, from the military to industry to academia; effective scouting for unusual or hidden talent will be critical.

Scan → Do → Review: structuring programmes for impact

Technical Directors should have a wide range of freedoms and tools to execute programmes, but there should be common elements that will underpin each programme stage. We recommend that UKDI adopt a Scan → Do → Review model:

1. Scanning

Threat-informed prioritisation

Technical Directors, with support from UKDI staff and the wider MOD, undertake intelligence-informed technology scouting, including classified analysis of threats and opportunities. While existing functions – such as those operated by DSTL – generate valuable intelligence and horizon-scanning insights, they are inconsistently translated into action. UKDI should aim to bridge this gap by integrating these inputs into a structured process that turns insight into programme design. The goal is to move from general awareness to targeted technology acceleration aligned with operational needs.

Technology intelligence scanning should be international, include open source data, and capitalise on the UK’s intelligence sharing arrangements. This should be complemented by industry scanning, including engagement with startups, national labs, and strategic suppliers. Scanning should also be alert to system-level opportunities – where combining technologies or reconfiguring existing capabilities could unlock greater operational effect – and should connect to upstream concepts and doctrine from Defence Futures. The aim is to develop clear problem statements that align with military capability gaps and future force requirements.

2. Execution

Expert Technical Directors running high-speed programmes

Technical Directors construct programmes that deliver on each problem statement at speed. Activities will be mid- to late-stage R&D, performed by UK-based companies and research and technology organisations (RTOs). With support from wider unit staff and other trusted organisations, Technical Directors break down classified requirements into solvable industry challenges, with clear success metrics for each.

Crucially, they will work closely with SciAds (MOD’s network of Science Advisors) and service-level capability owners to ensure operational pull from the outset. This is not a downstream consultation exercise: warfighter input will shape programme direction, use cases, and success criteria – ensuring that UKDI programmes are aligned with real tactical need and capable of closing the lab-to-field gap. Challenges should be framed to maximise dual-use potential and seed early markets for high-value UK technology firms.

Each programme will run to a tight execution cycle, drawing on rapid project delivery in the private sector (e.g. concept-to-production pathways in automotive and motorsport), which might look like:

- Phase 1: 6-month rapid technology assessment.

- Phase 2: 6-month prototype development.

- Phase 3: 6-month validation & military integration.

For this model to work, Technical Directors must be completely free to deploy resources as they see fit, with direct budgetary control and a direct relationship with industry. Speed of funding decisions should be a defining feature – with an expectation that decisions can be made within 14 days, as demonstrated by models such as Fast Grants. Where competitive processes are necessary, they should be purpose-built for pace and proportionality: streamlined, low-burden, and tightly aligned to a critical path.

Technical Directors should also be supported to undertake flexible contracting, for example with novelty-seeking startups that use a modular approach to rapidly build and test new technologies, run rapid procurement cycles and, where needed, deploy novel procurement routes such as advanced market commitments. Whatever the funding mode, lengthy bid development cycles, complex documentation requirements, or extended approval timetables must be actively avoided by design.

Technical Directors could use a variety of funding mechanisms, including:

- <£500k, early innovation grants for promising TRL 4-5 technologies, with rapid deployment of funds (noting that hardware solutions will require more funding than software/digital solutions)

- £250k - £2m, development contracts for TRL 5-7 with milestone-based payments tied to technical criteria.

- £2m - £15m, strategic investments for TRL 7-9, with emphasis on sovereign capability, supply chain development, and export potential.

FSC-approved organisations should support and facilitate programme execution – for example, certain High Value Manufacturing Catapult centres, the National Physical Laboratory, other select PSREs, and trusted higher education institutions with advanced TRL capabilities and strong industrial integration – especially where these platforms are already closely engaged with MOD and defence primes.

Activating the research and innovation ecosystem

The UK’s research and innovation ecosystem is underused in defence contexts. UKDI can help unlock its potential by providing a clear, time-bound route for research organisations to contribute to sovereign defence outcomes. With its scale and reach across this system, UK Research and Innovation could become a key strategic partner to UKDI, supporting both early-stage innovation and the activation of UK supply chains.

To ensure effective handoffs at programme termination, Technical Directors should develop a translation roadmap that includes:

- plans for stakeholder engagement

- strategies to anticipate and mitigate regulatory barriers

- clear scaling pathways into procurement or operational use

- where appropriate, approaches for commercial exploitation and for retaining economic value and IP within the UK.

UKDI will need to engage closely with Defence Equipment & Support, Front Line Commands, or dedicated MOD champions to develop seamless handoffs.

3. Review

No-nonsense kill/scale decisions every 6-9 months

A core principle of UKDI should be a ruthless focus on delivery. If a technology fails to address its problem statement, it is cut – and resources are redeployed at pace. At each go/no-go gateway, technologies will be scientifically performance-checked and, if they meet the criteria defined by the Technical Director at programme initiation (i.e. effective, scalable, operationally viable), transitioned into procurement or operational testing.

This transition is not a side issue: UKDI’s success will ultimately be judged by whether its programmes result in deployed capabilities. That requires MOD commitment, but traditional pathways are slow, and reform will take time. UKDI must prove its value on a faster timescale.

It should therefore be designed to operate effectively even if the wider system remains unchanged. This means building practical transition mechanisms from day one: including budgetary flexibility for early-stage adoption, limited exemptions from standard approvals processes, and dedicated fast-track routes into procurement or operational testing. These tools will allow UKDI to deliver real impact in the near term, while also providing a blueprint for how the system as a whole might evolve.

Alongside this, UKDI should work with the National Armaments Director and the Department for Business and Trade to explore export and commercialisation routes, and with the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology to identify opportunities for dual-use and spillover impact, particularly in AI and advanced manufacturing.

Governance and risk management

UKDI’s success will depend on its risk appetite – a high tolerance of failure complemented by an aggressive approach to stopping failing programmes. To this end, UKDI must sit outside traditional bureaucratic constraints of hiring, spending controls, procurement rules, onerous Managing Public Money (MPM) requirements, and regular budget cycles. UKDI should be afforded the same level of freedom as the Vaccines Taskforce from the outset.

These freedoms should be enshrined in statute, drawing on the model of the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA). But UKDI should not replicate ARIA’s institutional distance from government. Unlike ARIA, UKDI will require direct operational alignment with defence objectives and classified access from the outset. The goal is not institutional independence, but mission-driven autonomy aligned with national security.

While Technical Directors will own technical risk at the programme level, the overall tolerance for strategic risk-taking will depend on strong, independent leadership. To ensure bold decision-making and a relentless focus on delivery, the unit should be led by a Chair with a proven track record of driving high-risk, high-impact innovation.

The appointment of a serious Chair with a high degree of political cover and real autonomy is essential for UKDI’s success. Without this, UKDI risks becoming another underpowered initiative constrained by the very system it is meant to overcome.

The Chair should:

- Be external to the existing defence and civil service structures, ensuring they bring fresh thinking and are not constrained by traditional bureaucratic incentives.

- Have the credibility and independence to challenge institutional inertia, setting an ambitious pace for execution.

- Be accountable at the highest levels of government, reporting jointly to the Prime Minister and the Defence Secretary, reinforcing UKDI’s status as a strategic national priority, and providing the political cover needed to secure (and operate within) the freedoms described above.

Security risks will be managed with appropriate classification and handling procedures, strong collaboration with the UK intelligence community on threat assessment, and strategic counterintelligence support to protect key technological advantages.

Managing institutional resistance

As a new body, UKDI will inevitably face resistance from established stakeholders in the defence ecosystem. This may take the form of procedural obstacles, competing priorities, or concerns about disruption to existing programmes.

The Chair and Technical Directors should engage proactively with key stakeholders across MOD, industry primes, and Front Line Commands – not to seek consensus, but to build advocates rather than adversaries. This should include regular briefings on UKDI’s progress, early identification of transition partners for promising technologies, and, where appropriate, collaborative programmes that demonstrate UKDI’s additive value to the wider system.

The goal is not alignment on every decision, which would dilute UKDI’s mission focus, but sufficient institutional support to allow Technical Directors to deliver at pace without undue interference. This cannot substitute for high-level political sponsorship, but it can help UKDI gain traction within the system.

Plan of Action

There is no reason to delay. The Government should immediately establish a UKDI Task Force. With significant political push from No.10 and an ambitious and empowered Chair, an initial wave of programmes could be up and running within 12 months. In parallel, work should begin to establish UKDI on a long-term statutory footing, providing the Cabinet Office with assurance that the temporary arrangements needed for UKDI can be managed without setting precedent for wider government.

Step 1: Secure exceptional permissions and political cover

Key departments will need to be engaged early to lock in the flexible permissions that are critical to UKDI’s success:

- HM Treasury and MOD to agree to exemptions from standard MPM constraints and spending controls with budget agreed through a single business case and spending authority delegated to the Chair.

- No.10 and MOD to agree on a clear risk management framework with ministerial-level backing.

- Civil Service Commission to agree to exceptions for recruitment processes and pay bands (following AISI precedent), and No.10 to be engaged on the appointment of UKDI Chair.

- Cabinet Office to be engaged on UKDI’s positioning as an accelerated, mission-driven innovation body outside of standard procurement procedures, and National Security Secretariat to agree to fast-tracking security clearances.

- Cabinet Office (Public Bodies Reform Team) to be engaged on longer-term establishment of UKDI as an ALB.

Step 2: Recruit a high-calibre founding team

The urgent shared priority should be to hire exceptional people extremely quickly:

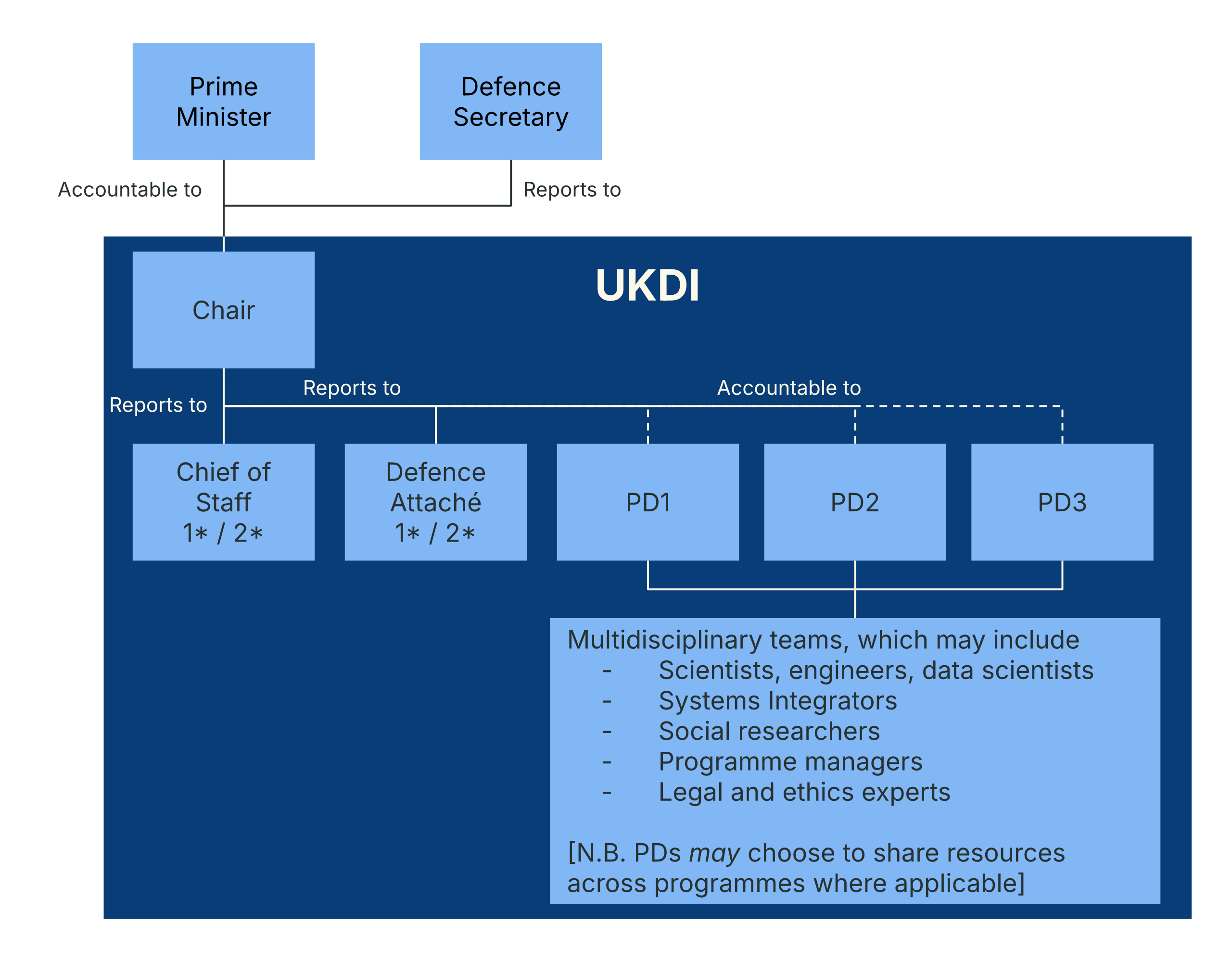

- The initial core team will comprise the Chair, two civil servants (SCS Chief of Staff and Military Attaché), and up to three Technical Directors. The Chair will be accountable directly to the Prime Minister (following Vaccines Taskforce precedent). The civil servants will be positioned in the Defence Secretary’s Private Office, reporting to the Chair. A high-level organisational chart is set out in Figure 1.

- Direct ministerial appointments will be used for initial hiring to bypass lengthy processes.

- In the fully formed UKDI, Technical Directors’ role profiles will be determined by the technology gaps that UKDI seeks to address. However, the MVP Technical Directors should be highly capable technical generalists, such as systems integrators or technical polymaths, with broad knowledge across defence technology domains. These Technical Directors would rapidly identify priority capability gaps and subsequently shape detailed role profiles to closely match programme requirements. All Technical Directors should also be recruited based on their ability to manage multidisciplinary R&D programmes and work effectively with the UK supply chain (they will not be recruited using the Civil Service ‘behaviours’ or ‘strengths’).

- These individuals will be rare, but UKDI will be designed to find and empower them. Active talent scouting, international secondments, and exceptional hiring flexibilities will be essential to attracting candidates with the systems-level mindset and technical breadth required.

- Technical Directors will then have the flexibility to hire expert, multidisciplinary teams as necessary to run their programmes.

- UKDI will need access to facilities with appropriate classification capabilities.

Figure 1: A high-level organisational structure for UKDI

Step 3: Undertake military capability needs assessment

During the MVP phase, UKDI’s priorities will be strongly informed by a top-down capability needs assessment (with bottom-up technology scanning to be integrated as it scales):

- UKDI will work with MOD to identify an initial list of target military capability gaps, based on prioritisation criteria such as urgency of military need, potential to provide asymmetric advantage, and technical feasibility within a 24-month time frame.

- UKDI will then establish formal connections with military operational commands and user communities to test ‘on the ground’ views of the identified capability gaps.

- The target capability gaps will be iterated with Technical Directors and informed by their understanding of the technical landscape.

- This will ensure that UKDI addresses operational needs from day one.

Step 4: Launch focussed programmes and engage industry

Technical Directors will be required to:

- Launch their programmes within 6-9 month timeframes

- Implement the "Scan → Do → Review" operating model with clear Go/No-Go points and metrics

- Build an industrial engagement pipeline in the UK and coalitions with domestic primes, SMEs and non-traditional suppliers.

- The Chair will have operating space to leverage industry funding and involvement

- Target: a network of high-performing contractors which combines frontier research capabilities with practical engineering implementation

- Leverage innovation intermediaries (Catapults, National Labs) as needed

- Establish translation mechanisms to break down classified requirements into unclassified problem statements

Step 5: Evaluate, scale and embed impact

The Chair of UKDI will establish and report to the Defence Secretary and Prime Minister on clear success metrics at 12, 24, and 36-month intervals. Metrics could include:

At 12 months:

- At least 3-5 high-priority programmes launched with clear capability targets

- Establishment of streamlined contracting mechanisms with 80% reduction in time-to-contract compared to traditional MOD procurement

- Development of at least one operational prototype addressing a critical capability gap

At 24 months:

- Successful transition of at least 2 technologies to TRL 7+ with concrete plans for operational testing

- Demonstration of at least one capability that provides asymmetric advantage in a relevant operational environment

- Establishment of a network of at least 20 non-traditional suppliers actively engaged in UKDI programmes

At 36 months:

- At least one UKDI-developed technology in active operational use or formal procurement

- Documented evidence of 50% reduction in time-to-field compared to traditional acquisition pathways

- Economic impact assessment showing ROI through dual-use commercialisation and UK supply chain activation

The Chair will also be accountable for:

- Introducing and implementing a full technology and industry scanning function as a counterpart to the military capabilities needs assessment(s).

- Setting out a transition plan from pilot to enduring capability based on proven results.

- Establishing a long-term funding model and governance structure.

- Mapping UKDI’s alignment with broader industrial strategy goals, including a plan for capturing economic spillovers, mechanisms to retain UK IP ownership, license emerging capabilities, and seed commercial spinouts where appropriate. This may include contractual mechanisms to retain UK benefit capture, such as IP provisions or equity models, following the precedent set by the Vaccines Taskforce.

After the initial MVP phase, UKDI will benefit from being established as an arm’s-length body (ALB) to facilitate its further scaling into an enduring capability. Constituting UKDI as an ALB will provide several ongoing benefits:

- Persistence – a lasting institutional form and corporate memory that can withstand the structural and political changes to which Whitehall departments are more exposed

- Capability – end-to-end and right-sized corporate capabilities that are geared to UKDI operations (for instance, specialist IP lawyers and a strong commercial function)

- Freedoms – UKDI’s initially high level of autonomy can be taken forward in a partitioned way without difficult precedence for Cabinet Office

A sensible pre-existing model for establishing UKDI as an ALB can be found in the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) Act. ARIA has freedoms and powers which would be enabling for UKDI, though UKDI should retain a closer model of sponsorship than ARIA to ensure ongoing alignment with defence objectives/intelligence.

Budget

The Spring Statement 2025 ringfenced £400m for UKDI, which will increase in future years. It is recommended that a fully operational UKDI have an annual budget of 1-2% of the overall MOD budget, amounting to c.£600 million-£1.2 billion. For comparison, DARPA’s budget is c.0.5 to 0.8% of the DoD’s overall budget. However, 1-2% of the MOD’s budget is a modest sum in actual terms (MOD’s budget is c.9% of the DoD’s).

With UKDI’s budget directly delegated to Technical Directors (apart from the initial staffing and setup costs delegated to the Chair), this would minimise overhead and administrative costs.

Summary of expected benefits and impact

- Military capability advantages

- Faster fielding of disruptive technologies

- More responsive adaptation to emerging threats

- Enhanced interoperability with allies

- Greater operational flexibility through technological diversity

- Industrial and economic benefits

- Strengthened domestic defence-industrial base

- Creation of high-value jobs in advanced technology sectors

- Potential dual-use applications and commercial spillovers

- Enhanced UK technology sovereignty in strategic domains

- Greater economic return on defence R&D through planned dual-use and commercialisation pathways

- Innovation system benefits

- Improved connectivity between defence and commercial innovation

- New paths for academic research to transition to operational use

- Cultural change in defence technology development approach

- Model for other areas of government innovation

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following for generously providing their input and insights: Mark Spearing, Alex Chalmers, JP Chretien, Sam Currie, Joshua Elliott, Helen Ewles, Matt Clifford, Jamie Mackintosh, Graham Wren, Gabriel Elefteriu, Nitarshan Rajkumar, and numerous unnamed civil and public servants. All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Annex A: International examples

DARPA (US)

- Autonomous programme directors with significant discretion and minimal oversight

- High-risk, high-reward research portfolio focussed on technological breakthroughs

- Fixed-term appointments for programme directors (3-5 years)

- No permanent research staff, relying on external performers

- Key Lessons: Technical Director autonomy and accountability, time-limited appointments, risk tolerance

Strategic Capabilities Office (US)

- Focussed on repurposing existing technologies for new military applications

- Rapid technology maturation (18-36 months)

- Strong operational connections to military end users

- Emphasis on "the art of the possible" rather than perfect solutions

- Key Lessons: Speed of execution, operational focus, pragmatic approach to technology maturation

Vaccines Taskforce (UK)

- Direct government taskforce with extraordinary authorities during crisis

- Cut through bureaucracy to deliver results at unprecedented speed

- Clear mission focus with Prime Minister-level backing

- Empowered leadership with discretionary decision-making authority

- Key Lessons: Bureaucratic bypass mechanisms, empowered leadership, clear mission focus, risk tolerance

ARIA (UK)

- UK's Advanced Research and Invention Agency established to fund high-risk, high-reward research

- Designed with programme director autonomy inspired by DARPA

- Freedom from traditional bureaucratic constraints and procurement rules

- Focus on breakthrough science and technology

- Key Lessons: Regulatory independence, flexible funding mechanisms, tolerance for failure in pursuit of breakthroughs

SpaceX

- Rapid iteration and testing philosophy ("Test, fly, fail, fix, fly")

- Vertical integration of design, manufacturing, and operations

- Clear mission focus with defined technical milestones

- Emphasis on in-house capabilities and talent concentration

- Key Lessons: Speed of development cycles, tolerance for calculated risk, integration of design and manufacturing

Google DeepMind

- High concentration of top technical talent

- Mission-driven focus on AI breakthroughs

- Balance of fundamental research with practical applications

- Technical leadership with decision-making authority

- Key Lessons: Multidisciplinary talent density as competitive advantage, long-term technical vision combined with practical capabilities

OpenAI

- Start-up speed and culture within a mission-driven organisation

- Iterative approach to technology development

- Technical leadership empowered to make rapid decisions

- Balance of research progress with operational deployment

- Key Lessons: Rapid product development cycles, scaling approaches, public-private interface management

Skunk Works (Lockheed Martin)

- Highly autonomous, classified advanced development projects

- Small, elite teams with minimal management layers

- Rapid prototyping and testing culture

- Strong end-user engagement throughout development

- Key Lessons: Elite team structure, minimal bureaucracy, rapid iteration

BBN (Bolt, Beranek & Newman)

- Early contractor for DARPA that became the "third university of Cambridge"

- Successfully bridged academic research and practical engineering implementation

- Combined top technical talent with professional contract management capabilities

- Structured to tackle projects requiring both cutting-edge academic knowledge and rigorous engineering

- Delivered the first nodes of ARPANET on time and on budget, building on years of related work

- Key Lessons: Building innovation ecosystems requires not just programme directors but exceptional performers; technical vision can be pursued through strategic contract work; creating "translation functions" between classified requirements and industry solutions

Annex B: How this model differs from existing structures

Existing institution | Role | Limitations | Complementarity with DITF |

DASA | Open innovation funnel | Identifies innovation opportunities through open calls and competitions. Not set up to address specific capability gaps. | Works with DASA to identify promising early-stage technologies for acceleration |

DSTL | Long-range defence S&T research | Focussed on fundamental or exploratory research rather than structured technology acceleration. Research often doesn't transition into deployable capability at pace | Leverages DSTL research outputs and expertise while adding acceleration capabilities |

UKRI / Innovate UK | Broad research and innovation support | Primarily supports broad-based, systemic R&D and innovation outcomes, not defence-specific requirements. Posture aligned with civilian R&D priorities | Provides a pathway for dual-use technologies developed with UKRI funding to find defence applications. Catapult network useful for industrial activation |

ARIA | High-risk research | Designed for high-risk research rather than defence mission-driven innovation. Lacks classified access, operational focus, and military integration pathways | Complementary focus on different parts of the innovation pipeline, with potential to transition ARIA discoveries into defence use cases |

Defence primes | Major system integration | Focus on large platforms and long development cycles, less agile for rapid technology insertion | Provides a pathway for innovative technologies to be integrated into prime contractor platforms |

MOD R&D budgets (outwith agencies) | Scattered innovation funding | Fragmented across various commands, lacks concentrated effort on strategic technology acceleration | Consolidates strategic technology acceleration under expert leadership with clear mission focus |

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]