Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction: When Britain Built the Future

- 2. Conservatism versus Dynamism

- 3. Borrowing versus Building

- 4. Impotence versus Courage

- 5. Why We Set Up the Centre for British Progress

- 6. Authors

- 7. Acknowledgements

In 1870, a humble piece of paper measuring just a few inches across quietly revolutionised Britain. The introduction of the prepaid, standard-issue British postcard, priced at a mere halfpenny, slashed the cost of communication and expanded the boundaries of people’s lives.

Suddenly, anyone could cheaply and reliably send a message to anyone else, anywhere in the British Isles. A forge in Sheffield could order coal from Welsh valleys. Shipbuilders in Belfast could invoice clients in London, and expect a reply by the end of the week. Artists in Stoke could take commissions from patrons in Dundee.

.png)

.png)

First British halfpenny postcard, 1870 | “First issued British Postcard, 1870, PC.01.02b”, public domain via The Postal Museum; Penny Black postage stamps for letters, 1840 | “Penny Black Block of six” by General Post Office, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Before this postcard, communication had been costly and complicated – a luxury largely beyond the reach of ordinary families and small businesses. Sending letters was unpredictable and expensive. While the General Post Office's invention of prepaid stamps reduced fraud and friction, it was the halfpenny postcard – cheaper than a stamp and requiring no envelope – that truly delivered communication to the masses.

The postcard’s success was the culmination of decades of technological innovation. New and better printing methods, particularly the steam-powered press, drastically reduced the cost of production. The rapid expansion of the railways, driven by advances in steam power, surveying, and engineering, allowed swift, reliable, nationwide distribution. These industrial advances were vital preconditions.

But it was the machinery of the state that gave the postcard its true power. Beyond the introduction of stamps and postcards, a national postal system ensured that every corner of the British Isles could be reached. The postcard was the first step towards rapid communication networks, such as the state-backed telegraph system, that catalysed Britain’s industrialisation and shaped today’s world.

For ordinary people, the postcard meant more than cheaper communication. Families could move with greater confidence to cities and towns for work, secure in the knowledge that relatives were always just half a penny away. Traders found new customers, and households’ choices were expanded — a single scribbled line could bring soap from Liverpool or salmon from Scotland directly to one's door. Lovers separated by distance could now maintain a daily dialogue, secrets carried faithfully by these slips of card.

.png)

Women’s suffrage campaigns used postcards and cheap printing to spread their message | “Votes for Women poster”, public domain via Rawpixel Ltd.

But perhaps the postcard’s greatest legacy was as an instrument of political awakening. The social movements that defined the late 19th and early 20th centuries were mobilised around this modest innovation. Trade unions rapidly organised workers across cities and towns. Campaigners for women's suffrage embraced postcards as tools for conveying messages, instructions, and solidarity. By the dawn of the twentieth century, Members of Parliament were receiving thousands of postcards from their constituents demanding housing reform, workers' rights, and the protection of children.

Each postcard was a voice – a voice previously unheard – that collectively laid the groundwork for the defining social reforms of the modern age.

Through the confluence of technological progress, institutional ambition, and human ingenuity, this small, state-backed invention transformed the fabric of everyday life in ways unimaginable just a generation earlier.

The arc of human progress is marked by moon landings and soaring skyscrapers. But also by quieter revolutions, like that of the halfpenny postcard.

Introduction: When Britain Built the Future

Human progress depends upon material advancement – the development of new technologies, infrastructure and products that expand human capability. Material advancement, in turn, depends upon economic growth. Growth is not an end in itself: it matters because it expands our capacity for true human progress – lifting living standards, broadening opportunities, and giving people the freedom to build better futures.

Britain, at its best, has not only understood this, but embraced it more wholly than any other nation. With industrialisation, the people of these isles were the first to be freed from the iron grip of scarcity. It was here that the first sparks of industry fanned into flames of progress – forging an entirely new path not just for Britain, but for the world.

Humanity’s first experience of widespread material abundance spurred something even more precious: social and moral progress. From political liberalism and the extension of the franchise to improved education and healthcare, a cascade of human betterment flowed from the prosperity of industrialisation. Surplus time and energy gave many ordinary British people the capacity to create, to imagine, and to discover, enabling ever larger swathes of the population to lift their sights higher and see beyond the horizon of mere survival, towards lives of meaning, purpose, and possibility.

Every great British achievement – from the NHS to the defeat of fascism, from Brunel's bridges to the eradication of smallpox – emerged from our capacity to marshal material resources towards ambitious common purposes.

This ability allowed Britain to build the world we live in today. The theoretical foundations of electricity, computing, antibiotics, and the jet engine were all laid here. IVF, the World Wide Web and fibre optic cables were pioneered by British ingenuity. British scientists split the atom, discovered evolution, and unlocked the secrets of DNA. Our creators, engineers, and inventors defined the modern age.

.png)

Material progress delivers social progress: A map of London’s sewage system (1882) | “Hering lon-sewer-det02 1882”, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; “Anenurin Bevan, Minister of Health, on the first day of the National Health Service, 5 July 1948 at Park Hospital, Davyhulme, near Manchester (14465908720)”, by University of Liverpool Faculty of Health & Life Sciences, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

British ingenuity and economic prosperity have always gone hand in hand. Technological advances radically reduce the cost of production, creating material abundance and unlocking fresh capital for further innovation – a virtuous cycle of growth and invention. Newfound wealth creates choice for households, which in turn fuels demand for new products and services. Cheaper transportation opens up export markets, and facilitates the mobility of talent and investment. Sustained economic expansion propelled Britain into the ranks of the world's wealthiest nations, powered by those extraordinary inventions and discoveries that defined us.

But in recent decades Britain has stagnated. Economic growth has drastically slowed, investment is low, and wages and productivity have flatlined. For the first time in living memory, our children are expected to be worse off than their parents.

Our failure to grow has a human cost. Stagnation matters because it is ordinary families who suffer most, robbed not only of economic means but of confidence in the future. Britain's decline isn't just charted on graphs of GDP. It is etched onto the damp walls of neglected rental flats, shuttered shop fronts on bleak high streets, and the crumbling concrete faces of our schools. It can be felt in the stomachs of the four million children who go without enough food each morning; in the long, anxious wait – now averaging 14.4 weeks – just to start NHS treatment; and in the hollowed-out lives of 326,000 people in temporary accommodation—most of them families with children, caught in limbo with nowhere to settle and no place to grow.

There can be no compelling account of British renewal that does not place material progress and economic growth at its heart. Growth creates the fiscal space governments need to act decisively, allows citizens to look forward with ambition, and equips society with the resources to tackle big problems. Growth is the bulwark against society turning on itself – fighting over diminishing returns, rather than building toward a shared and expansive future.

But growth and progress will not return without effort. They must be chosen, championed, and purposefully prioritised. Above all, we must rediscover our national instinct to imagine beautifully, and act boldly.

The Cost of Choosing Decline

Britain’s stagnation is a break from historic and international trajectories. We are not just growing slowly, but falling behind. Since the global financial crisis, the country has experienced one of the weakest periods of economic growth in over two centuries. On key measures, we have diverged not only from our own past trajectory, but from other advanced economies.

The average British family is getting by with 19% less than if our growth trajectory had continued on the same path as before 2008 - equivalent to just under £7,000 per household. We are also just under 19% poorer than if we had kept pace with the US. Instead, we have seen a prolonged stagnation that predates the pandemic and Brexit, and has proved more severe than in most of our European peers. This is not just a temporary blip, but a structural failure of our political economy.

The British people are no strangers to hard times. In our finest hours we've reinvented ourselves in response to global upheaval. But reinvention and renewal are never guaranteed. Today, tectonic plates are shifting, carried by powerful technological and geopolitical forces – from the return of great power competition to artificial intelligence. These global trends are reshaping not only markets, but also the way we work, create, and find meaning.

Britain was once the master of these trends, harnessing them for prosperity and social advancement. But today, it feels like the future is being built elsewhere. Our nation, which once piloted the craft of progress, is adrift, carried in the slipstream of twenty-first-century superpowers. The technological and economic might of such nations not only sets the global agenda, but steadily exports their values, priorities, and visions of society.

The challenge is therefore not simply economic – it strikes at something deeper: Britain’s place in the world and our national sovereignty. We need a strong voice in the decisions that shape humanity’s future. Growth, above all, grants us that power. Our strategic choices, our diplomatic influence, and our national security are downstream of our prosperity. To defend our interests, we must first build an economy strong enough to sustain them.

Today, Europe finds itself increasingly isolated, its share of global economic output smaller than at any time since the Second World War. Though our economic malaise has its own unique characteristics, stagnation is shared by many European countries. The US, in contrast, has seen impressive economic growth, but is charting a path that subverts many liberal democratic ideals. Europe's economic stagnation presents a fundamental challenge: if the only way of being liberal and democratic is being European and poor, it is no wonder that faith in our shared values has eroded. We must prove that liberal democratic societies are capable of thriving in the 21st century.

For those who cherish freedom, justice, and social democracy – values which still largely unite the people of Britain – the stakes are high. Between European stagnation, America-first belligerence, and Chinese techno-authoritarianism, we must find an alternative path. It is incumbent upon us to demonstrate to future generations and the world at large that such ideals are not relics of a different era, inconsistent with today’s technologies and threats. Instead these values should drive, and find full fruition in, our shared prosperity.

What Went Wrong?

Had families across Britain woken up one day to find themselves 19% poorer, we would speak of a historical calamity. The full focus of our leaders, and all of us, would be marshalled – as though we were a country at war. Instead, successive governments have allowed a tepid decline to happen on their watch. Britain’s economic decline is not the result of a single crisis or policy failure. It is the product of repeated political choices on both sides of the political spectrum.

The modern right has claimed to champion growth, but failed to advance this aim with a coherent vision for social progress. Their playbook, by accident or design, encourages extraction: promoting rent-seeking, capitalising on division, and failing to invest in our foundational infrastructure, leaving Britain ill-equipped for the shocks of the past decade. Austerity brought public services to their knees on the eve of the pandemic. The unforgivable inability to build – particularly housing, transport, and energy infrastructure – will be felt for generations. But most importantly, this approach has failed even by its own standard: growth has not materialised. Instead, the economic model pursued by the modern right has consistently favoured existing owners of assets, dampening dynamism and extinguishing those sparks of creative productivity that Britain needs.

Meanwhile the left of recent times has often treated growth and the pursuit of material abundance with suspicion. Legitimate concerns about inequality, environmental damage, and corporate excess have given rise to a politics more comfortable with redistribution of dwindling resources and regulation than prosperity and progress. Redistribution remains an essential lever of politics – growth alone will not guarantee prosperity for all, especially if its pursuit is not married with active choices to deliver social improvement. But a country’s freedom to redistribute is downstream of its ability to grow. The ultimate effect of neglecting growth has been to harm the very people whose interests the left claims to protect, limiting their opportunities and their capacity to build better lives.

It may be true that in times of prosperity and favourable economic headwinds, as we enjoyed from 1997 to 2007, relying solely on the levers of redistribution and regulation can sustain social advancement. But in an era defined by stagnation, we need a new approach. Our theory of change must now encompass a theory of growth.

Because growth, at its core, is a progressive agenda. It is not the wealthy who most need growth, but the poor. The privileged quarters of society are insulated from the harsh realities of scarcity: they do not struggle with overcrowded classrooms, ration heating through the winter, or depend on unreliable buses. They are not left vulnerable by overstretched public services or waiting desperately on hold for support that does not arrive. When growth stalls, it is those with the least who suffer most.

Without growth, the state struggles even to fulfill its basic responsibilities, and public services become sites of triage that manage scarcity by rationing care. Politics degenerates into a fractious contest among interest groups, squabbling over meagre rations, and creating fertile ground for charlatans and populists. Our social institutions are choked, our collective horizons shrink, and our communities are impoverished.

Without growth, progressives can aspire only to soften the blows dealt by a broken economic model – one incapable of creating the meaningful, productive work upon which dignity depends. Challenges such as climate change become bleak, zero-sum trade-offs between present and future, dividing communities rather than uniting them around shared purpose. Businesses lose both the incentive and capacity to invest in our future productivity, while workers and families are constrained by the daily calculus of survival, unable to glimpse – let alone grasp – the possibilities of abundance.

This failure carries consequences that extend far beyond the material. It corrodes our civic life and weakens Britain’s place in the world. When politics cannot deliver prosperity, or even adequately perform its most basic tasks, the legitimacy of the entire political system begins to erode. Trust frays, and the democratic fabric becomes vulnerable to grievance, apathy, and division.

To truly understand what went wrong, we must look beyond the surface and confront the deeper structural decisions that have brought us to this place. We believe that three broad choices, embedded in our public institutions and reinforced by entrenched incentives, have constrained Britain's potential – and propose three alternative choices to reclaim progress.

- The choice between conservatism and dynamism

- The choice between borrowing and building

- The choice between impotence and courage

The work of choosing a different path – of moving from drift to direction – should be the defining political and cultural project of our time. The challenges are deep, but so too is our capacity for renewal. If we can summon the will to act, and rise decisively to this moment, the future could once again be imagined and created on these islands.

Conservatism versus Dynamism

British institutions have become quietly addicted to caution. This is not a partisan impulse, but a deeper reflex embedded in our public life, our boardrooms, our research institutions, and even our collective imagination. The conservatism we describe is not characterised by the vigorous preservation of what is best in our traditions, but a passive, default preference for the status quo – the reflexive defence of the established way of doing things, a suspicion of change, and an aversion to risk. This cautious impulse is a comforting fiction: it pretends that avoiding risk means avoiding decline, when in reality it all but guarantees it.

The opposite of this conservatism is dynamism. Dynamism demands precisely what many British institutions now lack: the courage to take risks, the confidence to discard practices that no longer serve us, and the energy to shape our future, rather than clinging anxiously to our past.

Where conservative systems reward stability, dynamic ones reward creativity, experimentation, and renewal. Dynamic businesses embrace originality and make big bets. Dynamic governments welcome new ideas, swiftly adopt better methods, and abandon failing processes. A dynamic society is one where the weak can challenge the powerful, where people rise or fall on their own merit, and where those from ordinary backgrounds are empowered by the knowledge that their lives – and their country’s destiny – remain open-ended projects, waiting to be realised.

The Cautious Economy

Britain is too beholden to a pervasive conservatism that runs through the veins of public institutions. It shapes what we study, where we work, how we save, and what we build.

British graduates are significantly less likely to start companies than their American counterparts, gravitating instead towards the relative safety of professions such as law, accountancy, and consultancy. British households save more of their money in bank accounts, rather than invest. When we do invest, our pension funds prefer safer bets, leaving us poorer.

At the firm level, the pattern persists. British companies invest less in capital, R&D and innovation than comparable firms in other advanced economies. Far from deploying new technologies to gain competitive advantage, many firms remain locked into low-productivity models, and face few consequences for doing so. In these ways, Britain exemplifies a general rule observed by British historian Donald Cardwell: societies that once led in innovation often become cautious and resistant to new technologies, ultimately ceding technological leadership to more dynamic competitors.

These patterns do not reflect any shortage of ambition or creativity among the British people. Choices are shaped by and interact with institutions and incentives, and Britain’s economy institutionally encourages conservatism over dynamism.

The design of Britain’s economic institutions has tended to favour stability over experimentation, size over growth, and incumbents over challengers. The result is a business environment that discourages dynamism, holding us back from the frontiers of technological innovation and economic productivity.

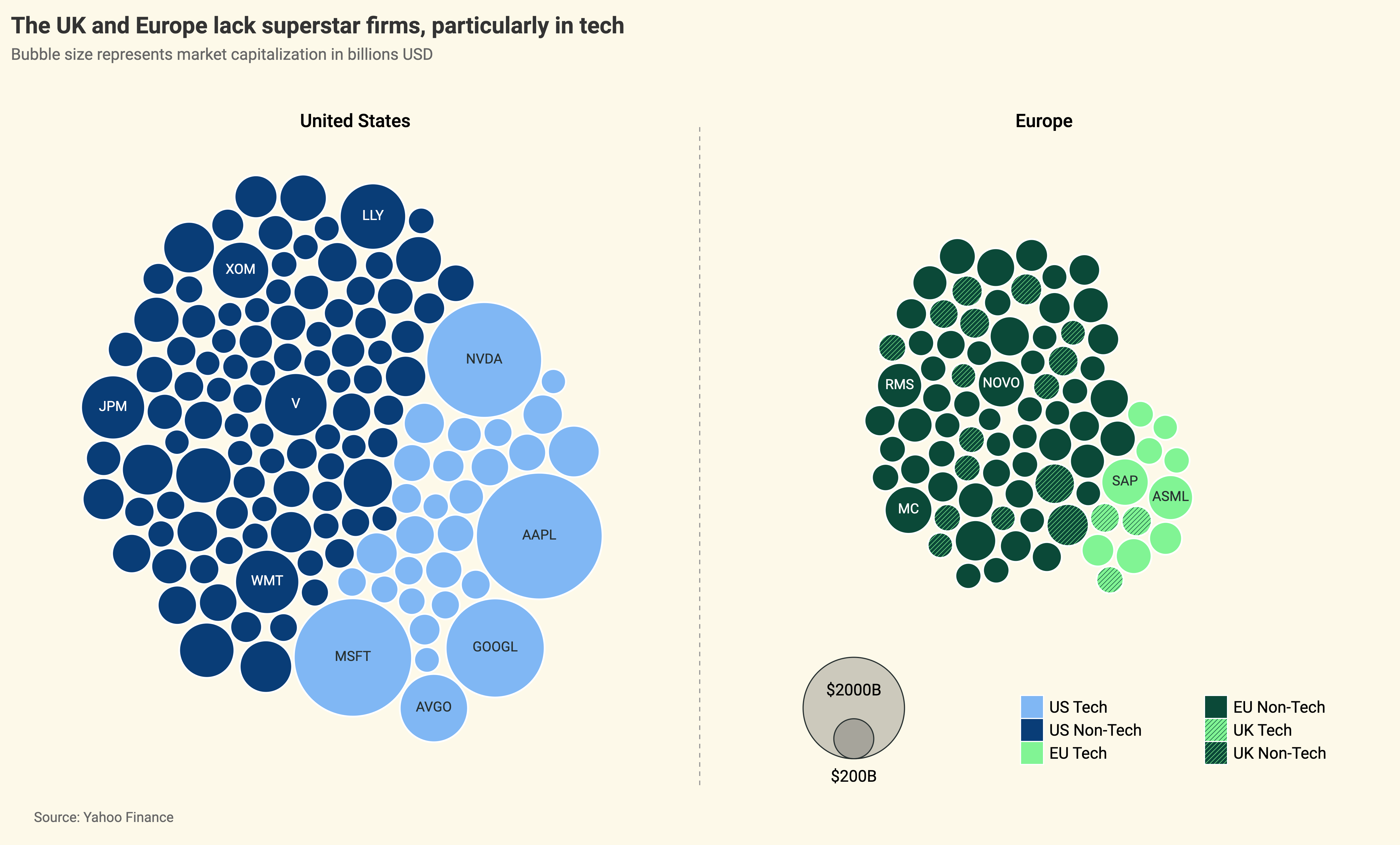

This institutional caution is demonstrated clearly in Britain and Europe's striking lack of ‘superstar’ firms. While the United States boasts eight companies valued at over a trillion dollars, – seven of them founded in the last half-century, and most in technology – Europe's most valuable company, Novo Nordisk, is worth less than half that. Britain's largest, AstraZeneca, is worth about half that again. America's corporate landscape is dominated by dynamic young companies unafraid to disrupt established industries, with new entrants able to take on incumbents and push the frontier of scientific and technological discovery.

In Britain, by contrast, new firms struggle to break through. Few grow quickly. Fewer still go global. Structural factors – such as fragmented domestic markets and higher expansion costs – have naturally limited the scale of UK businesses. British and European competition policies, which should empower challengers to take on incumbents, have often focussed too narrowly on stopping firms from getting big, rather than ensuring the conditions exist for new ones to grow.

Regulatory authorities often block mergers and acquisitions based on indirect and static metrics, such as the number of companies in a market and their market share, overlooking a more dynamic understanding of competition that includes a focus on removing barriers to entry. While size undoubtedly matters, regulators have often given it undue prominence – arguably this was the case with the 2019 £12 billion Sainsbury’s-Asda merger, or Meta’s $315 million acquisition of Giphy.

The presence of very large companies in an ecosystem is not only consistent with innovation, but can actively drive it. Their scale grants them the latitude to absorb risks, fund ambitious R&D, and invest at scale, and recent economic history shows that they can play a positive role in funding future cycles of discovery. But this potential depends on a deeper condition: that they remain exposed to the threat of competition. The incentive to innovate depends on the threat of usurpation. The truest measure of economic dynamism, therefore, is how easily and how often challengers can enter the market: contesting incumbency, and ultimately displacing the old guard, if they are better.

Yet too often in the UK, this competitive pressure fails to materialise. Institutional barriers to entry are real, and growing. Regulatory burdens are often designed with large, established firms in mind, and so disproportionately impact smaller, younger competitors.

The consequences are most clear in sectors where innovation collides with outdated or overly restrictive regulatory frameworks. Policies like GDPR have constrained profits for small European tech firms by up to 12%. Archaic legislation, like the Highways Act 1835, prevents productivity-enhancing technologies such as delivery robots from even entering the market. British bankruptcy laws remain punitive by international standards, discouraging healthy risk-taking and dampening the incentives to build. Copyright regimes protect incumbents rather than encouraging development and creation. In short, we have created conditions under which ambitious, talented individuals avoid building altogether – or build elsewhere. The UK ranks fifth globally in producing founders of US-based unicorns. The talent is there. The platform is not.

.png)

Starship delivery robots in Milton Keynes, which has an exemption from the nationwide ban on delivery robots | “Starships at Kingston 15.2.19” by Sludge G, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This is not an argument against regulation itself, which, when well crafted, can greatly benefit both consumers and markets. The state has a critical responsibility to uphold standards, ensure fair play, and protect the public good. But it also carries a complementary duty: fostering conditions that encourage innovation and economic progress. For far too long, British institutions have weighted the scales, tipping the balance towards caution and continuity, rather than dynamism and renewal.

The result is a stagnant economy in which rent-seeking is often more profitable than risk-taking. Incumbents have every incentive to defend their position – and will fight hard to retain their advantage and erect barriers to market entry. Investors will always prefer subsidy and government-backed guarantees to internalising the costs when bets don’t pay off. And policymakers are routinely lobbied to shield the old rather than build the new. It is precisely this entrenched resistance that makes dynamism a bold political choice; one that must be made if Britain is to reverse its decline and reclaim its potential.

Positive Pressure: The Force of Dynamism

Where competition is dulled and incumbency protected, even good ideas struggle to take root. A prominent manifestation of this inertia is the sluggish uptake of new technologies. In a dynamic economy, companies must modernise or die. But in Britain, the cost of doing nothing is often low. British firms are considerably slower to adopt new technologies than their peers in Europe and the US, and many firms continue to survive – even profit – while using outdated systems, unproductive tools, and obsolete workflows.

These self-imposed inefficiencies are a product of incentives that flow from an undynamic market. If barriers to entry are high, and competition is weak, then there is little pressure on incumbents to improve. Technological adoption becomes discretionary. In such environments, investing in innovation looks like an optional cost – one that can be safely avoided in favour of short-term returns or defensive consolidation. Business investment at the end of 2024 was at its lowest this century, under 8.7% of GDP, around half of what it was at the start of the millennium.

The result is what economists term allocative inefficiency: where resources – including talent and capital – stay locked inside ossified and underperforming firms and sectors. Meanwhile, new entrants that might use those resources more effectively find themselves starved of oxygen and struggle to grow. Productivity stagnates. Wages plateau. The economy drifts.

This challenge is not confined to the private sector. In the public realm, where there is no immediate external force or direct competition to compel improvement, the problem can be even worse. Technology adoption is patchy – if it occurs at all. Government departments continue to rely on systems that are decades old, while local authorities struggle to operate with minimal digital infrastructure. Basic services – from procurement to data management – remain analogue by default. Where appetite for change does exist (and there are many such places) swift action is nearly impossible. Promising innovations struggle to scale, even where they deliver better outcomes. Best practice goes unshared. Risk-averse procurement rules often favour the known over the new.

Adoption is the mechanism by which innovation delivers value – to consumers, to workers, to the wider economy. In Britain, that mechanism is broken. And until it is fixed, our innovation ambitions, however well-funded or well intentioned, will continue to flounder.

Rediscovering Britain’s Dynamic Energy

But the problem goes deeper than the adoption of new inventions. It is structural.

The British state was once a driver of innovation. In the 19th century, it took on vested interests to allow the building of railway infrastructure, nationalised the postal system, and helped lay the foundations for mass electrification and communications. In the 20th, it pioneered radar, developed early computing, and co-created Concorde. These were not reactive efforts – they were anticipatory: state-led bets on future possibilities.

.png)

The ‘All Red Line’ - a Victorian system of electrical telegraphs that connected much of the British Empire, completed in 1902, just 25 years after the technology was invented | “All Red Line” by George Johnson (1836-1911), public domain via Wikimedia Commons

.png)

.png)

The Colossus computer at Bletchley Park (1943) | "Colossus" public domain via The National Archives; Concorde’s first flight (1969) | “1er vol de Concorde (1969)”, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

A dynamic state is not just efficient: it is enabling. It builds platforms for innovation. It lowers the cost of doing new things, and actively derisks projects for the public benefit. It recognises that failing to adapt is, in itself, a risk – not just to public services, but to national prosperity.

The same state that helped lay the railways in anticipation of an age of steam must rediscover its dynamism.

Perhaps the greatest opportunity for Britain to anticipate future possibilities can be found in the nuclear energy sector. The next chapter in Britain’s nuclear history is about to be written, and the decisions we make now will determine whether we steer the ship of a global revolution in clean energy, or miss the boat entirely.

We once led the world in nuclear innovation. Calder Hall, opened in 1956, was the world’s first commercial nuclear power station. By the mid-1960s, Britain had constructed more nuclear reactors than the rest of the world combined. But since then, leadership has drifted abroad – to the US, China, France, and South Korea. The last nuclear power station Britain connected to the grid was Sizewell B, almost three decades ago.

The obstacles Britain faces here are not technological – they are institutional. Our approach is hampered by overlapping regulatory burdens, bespoke project requirements, and an aversion to standardisation. Projects lose years to protracted planning disputes and exhaustive environmental assessments. Safety regulations now impose standards far stricter than international norms – in some cases, mandating protection from levels of radiation lower than that occur naturally in parts of Cornwall. The result is astronomical costs and perpetual delays. Hinkley Point C will be one of the most expensive nuclear power plants ever built.

Britain’s current nuclear policy is a self-inflicted wound, damaging our prospects for economic growth, undermining energy security, and stalling progress towards Net Zero. Our failure to build nuclear power effectively is one of the main reasons for why the UK has the highest industrial electricity prices in the world. Meanwhile in other countries, the same reactors have been built faster, more cheaply, and just as safely.

These systems now face a critical test. A new generation of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) offers Britain an opportunity to reinvent nuclear power with standardised designs, factory-based assembly, lower capital costs, and rapid deployment. British firms are well placed to lead. Simultaneously, surging energy demands from AI infrastructure providers ensures a ready market. The opportunity awaits – if we choose to seize it.

In 2035, British workers could be building SMRs in factories across the UK and exporting them all over the world, reaping the rewards of an early bet on the next generation of nuclear power. This would be a quadruple win for the UK: nuclear provides energy security, cheaper bills, decarbonisation, and skilled jobs in deprived areas. But to get there, we must embrace dynamism, and let go of institutional habits that no longer serve us. That means streamlining regulation, accelerating planning approvals, modernising the grid, and opening the door to private investment. Above all, it means shifting from a mindset of eliminating risk to one of anticipating opportunity.

The Cost of Conservatism

A stagnant economy does more than slow growth – it narrows horizons. It denies people the chance to rise, to contribute, to flourish. In protecting the status quo, we entrench inequality, and in doing so erode our collective hope that tomorrow can be different from today.

In a society starved of dynamism, life begins later. People take fewer risks. The space to rise or reinvent oneself begins to narrow. Housing, a foundation of opportunity, becomes a gatekeeper. Education, designed as a great leveller, too often reinforces the inequalities it was meant to dismantle. Career progression hinges less on demonstrating capability than on the ability to navigate opaque systems. Advantage is reproduced, not disrupted. And as churn declines, so does belief in the possibility of change. Merit becomes mythology, which breeds resentment. The conditions for renewal slip away.

A dynamic economy is not just more productive – it is more just. It loosens the grip of inherited advantage. It spreads opportunity across regions and sectors, and revives the basic promise that talent, effort, and ideas still count, and can still change lives. Dynamism means laying the foundations of a country that can adapt and prosper in a world of constant change. A country that invests in its people, rewards effort and enterprise, and trusts itself to build great things.

Borrowing versus Building

Choosing the future also means choosing what to carry forward from the past – what to protect, what to build upon, and what to leave behind.

Britain is the cradle of industrialism and romanticism, and the tension between them runs deep in our relationship with the land. The coal that fuelled the industrial revolution lay beneath our feet; its extraction blackened the skies and scarred the hillsides. We raised great cities and the air became smoke. But Britain is also a land of quiet pastoralism and rugged coasts, of hedgerows, highlands, stone churches, and cliff paths. We want to build Jerusalem – but we also want our green and pleasant land.

.png)

J.M.W. Turner’s ‘Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway’ (1844), which captures both the awe and anxiety about industrial progress at the time | public domain via The National Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

This tension is not a weakness – it is part of our inheritance. It is not unBritish to build, but we are also right to value our heritage and preserve the unique beauty of these small islands.

Out of this friction we forged a precious skill. We are a nation that once knew how to build, not just quickly or cheaply, but beautifully. The same country that laid down 6,000 miles of railway track in a single generation also raised glass-and-iron railway stations that still crown its cities today. Victorian engineers made pumping stations with pride; postwar governments built civic cathedrals in concrete and brick. To build was not simply to solve a problem, but to project confidence – to believe that the future was worth investing in, and that public works could express public hope.

True progress enables building that is beautiful. When the Victorians built railway stations, they were making a big bet on a technology of the future: this required enormous capital investment and rapid scaling. Railway stations were in some ways the data centres or SMRs of today. And yet, Victorian railway stations were not just functional but also beautiful. An ambition for speed and scale was matched by an ambition for beauty and local pride. Even today, these Victorian cathedrals are the architectural centrepiece of many British towns.

-1.png)

-1.png)

.png)

.png)

These stations opened within 41 years of each other: (1) Paddington (1838), (2) Bristol Temple Meads (1840), (3) St Pancras (1868), (4) Glasgow Central (1879) | (1) licensed from Getty Images; (2) courtesy of Network Rail; (3) courtesy of London St. Pancras Highspeed (photo by Sam Lane); (4) licensed from iStock

Today, that spirit has faded. Consecutive droughts see reservoirs unbuilt. Energy grids creak under demand. Housing costs soar while new homes stall in endless delay. This is not for lack of land, capital, or need. It is because we have collectively chosen not to build, and forgotten how to build beautifully.

Instead, we borrow from the past: living off infrastructure, institutions and housing stock inherited from more ambitious generations. We borrow from the future: drawing down public goods without replenishment, leaving the costs to those who come after. And we borrow from each other: in a zero-sum contest over access and ownership, where wealth comes not from what we make, but from what we already hold.

The Country We Built

Some see Britain's national character as leaning more towards preservation than construction. But that is a selective reading of our past. The pastoral idyll has always existed alongside the workshop and the furnace. Ours is the country of Capability Brown and William Blake – but also of Thomas Telford, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and the vast physical inheritance they left behind.

The industrial revolution was not just a moment of economic transformation, but of civilisational ambition. We used to build things because we believed in what they stood for. Railways were not only arteries of commerce; they were a proud investment in a transformative technology. Manchester’s warehouses, London’s sewer systems, and Birmingham’s town halls were investments not just in functionality, but in the dignity of shared life. Even the Victorian brick terrace or the postwar semi spoke of a society prepared to house its people decently – and at scale.

That spirit carried into the postwar years. The New Towns of the 1950s and ’60s were designed with ambition and care, an effort to marry social need with architectural integrity. These projects were not perfect, but they were real attempts to shape the future. Today, that sensibility has eroded. When we do build, we build slowly, defensively, and joylessly. Infrastructure projects drag on for decades, their original purpose forgotten by the time they are completed, if they ever are. We no longer ask what our buildings say about who we are, or who we want to become. The result is a built environment that reflects our uncertainty – indistinct, cautious, and afraid to make a mark.

Borrowing from the Past

Much of what sustains British life today was built by previous generations. We still rely on the railways laid by Victorian engineers, the water systems they designed, the housing estates built after the Blitz, the schools and hospitals raised in the postwar social contract. These were the products of bold investment and collective will: visions of national life made solid in brick, steel and concrete.

But that legacy is aging, and it is not being renewed. Instead of building anew and investing in our future, we have opted to live off our inheritance. Our housing stock is among the oldest in the developed world: 20% built before 1920, 40% before the Second World War. And what has been built since is too little, too late. Young people today must navigate a housing market in which price and quality no longer correlate, and access is less about effort than timing.

Economic rewards no longer flow to those who make or build, but to those who own. Britain has become a place where productive effort is taxed, while the unearned gains from land and property are protected. The result is a distorted economy: one that hoards rather than creates, and that treats housing not as places to build lives, but as speculative assets.

This is not new. The economic historian Nicholas Crafts observed that Britain was able to industrialise and grow precisely because the industrial revolution shifted talent and capital away from the rent-seeking classes of church, law, and military, and into enterprise. But today, the tide is turning back. The modern rentiers are landlords, developers, and institutional investors, enriched not by creating value, but by an exclusionary system that forbids anyone from building.

When we fail to build, we create conditions in which rent-seeking thrives. Private interests gain not by creating value, but by adjusting the rules to entrench their advantage. Many landowners believe it more profitable to block development than to invest in new sources of prosperity. As the economy tilts toward rentierism, perverse incentives ripple through the system, distorting decisions for businesses and workers alike. Firms struggle to recruit, and global talent is repelled by the difficulty of settling here. Talent and resources are pulled away from the places they could be most productive, to the detriment of society.

But soaring prices and chronic undersupply are not merely economic concerns – they are barriers to mobility, independence, and aspiration. Workers are unable to move to take up job offers, or are forced to live further from their workplace, leading to opportunity costs from time spent commuting, and putting a strain on families. Young couples delay starting families. In cities across the country, record numbers of young adults live with their parents – not out of choice, but necessity. What we once built in abundance – decent housing, civic infrastructure, and a sense of possibility – we now ration, defer, and neglect.

In a society that builds, housing is a foundation for opportunity. In one that borrows, it becomes a gatekeeper.

Borrowing from the Future

A society that stops building doesn’t only live off its past – it borrows against its future. The costs of that debt aren’t always obvious in the present, but they are steadily accruing. Britain’s public services are fraying. Our schools, hospitals, power grids, and railways are stretched beyond their intended lifespan, and are asked to do more with less, decade after decade. Maintenance is deferred. Investment never arrives.

Meanwhile, the pressures intensify. The transition to net zero will require new energy infrastructure, grid capacity, public transport, and housing. A more volatile world will require a state that can act and build at pace. An ageing population will require more from health and care systems, while rising dependency ratio means that more will be borne by fewer. But instead of preparing for this future, we transfer the costs and risks to the next generation, in the form of underinvestment, degraded assets, and depleted institutional capacity.

In many ways, the social contract has been broken for Britain’s youth. Compared to their parents, young people today will transfer a far greater share of their income to landlords – and if they do manage to buy a home, they face larger mortgages paid off over longer spans of their working lives. Inheritance flows (the financial value of gifts after death) have surged in recent years, now approaching 10% of British national output – twice as much for those born in the 1980s as for the generation before. The old promise – that each generation might build a better life than the last –is receding.

None of this is inevitable. But it is the predictable result of a political economy that treats land as a store of private wealth rather than a platform for public value. A country that builds invests in its future; one that borrows merely defers the reckoning.

Choosing to Build Again

The case for building is, at its heart, a moral one. To build is to believe in, and provide for, the future – to act in the service of younger generations, and to make visible what we value as a society.

Choosing to build requires reforming the systems that block it. We will need radical reform to our planning system, but we could go even further by tapping the value locked in our land. Britain is, in many ways, a high wealth, middle income country. The median Brit is wealthier, in dollar terms, than the median member of any G7 country. This may look impressive on paper, but the median Brit does not feel any wealthier than their G7 peers. The wealth reflects inflated property values: our housing is worse than that in Germany or Canada, but it is much more expensive. Our median income is comparatively low among G7 countries.

The reason for this disparity is that the link between wealth and producing value to society (i.e. productivity) has broken down. In today’s Britain, the biggest determinant of someone’s wealth is not how much they have contributed to society through work, investment or industry, but when and where they (or their parents) bought a house. Britain’s inequality is not the result of entrepreneurs or big businesses reaping vast spoils from market success. It comes from pure, heritable luck. This system is protected by law, by making it hard to build new houses, and turning land into a speculative asset.

The UK is unusual in being a high wealth, middle income country

In addition to radical planning reform to build more homes, we must find ways of capturing the value of land and assets to invest in infrastructure for the future. Land value capture, used to help fund London’s Elizabeth Line, shows how rising land prices – driven by public investment – can be recycled into public benefit. Over £4.7 billion was raised through business levies and developer contributions to support a single project. Despite exceeding its budget and opening late, the line has transported over 350 million passengers within two years of opening, far exceeding projections of 100-130 million per year. But London shouldn’t be the only city that benefits from these mechanisms. We could use land value capture to help build a metro in Leeds, northern rail, or indeed new roads and utilities elsewhere in the country. Public investment should create public value, everywhere.

There are strong macroeconomic reasons to act. We want inventors to create new technologies, entrepreneurs to build companies, and workers to enjoy the fruits of their labour. What we do not want is rentierism – a system where wealth accumulates not through contribution, but through control. On this, socialists and free-market libertarians can agree: no one should grow rich by producing nothing of social value.

But our current system is largely geared towards taxing productive work, leaving passively accumulated wealth largely untouched. Those who care about equality and justice should recognise that in today’s economy, the most corrosive effects of vested interests are not found in the pursuit of profit, but in the consolidation of rentier power. Protected by law and reinforced by policy, this power suffocates productive investment, binding our national inheritance into inflated land values and rent-seeking industries that generate little benefit for wider society.

Yet no financial fix will matter without a shift in mindset. Britain can recover the sensibility that once defined our approach to building – not just as a technical act, but as a cultural one. We are a country where utility and beauty once went hand in hand. We can build things that work, that endure, and that express who we are. Cathedrals of modernity. Homes people can afford. Infrastructure scaled to our challenges.

Britain remains a wealthy country. The power to build lies not only in future innovations, but in the land beneath our feet.

Impotence versus Courage

If you ask what truly ails Britain’s institutions today, the simplest answer is neither incompetence nor malice – but impotence.

Britain lacks dynamism, and we need to build. But when our state tries to act, it often finds itself unable to deliver. This is not only frustrating for those trying to produce change, but also the British people, who deserve results. This continual disappointment can fester, breeding resentment and apathy, and eroding trust in the ability of government to deliver on its promises, or effect meaningful change in people’s lives.

The Everything Bagel

The American writer Ezra Klein, in diagnosing the strategic failings of progressives, coined the phrase “everything-bagel liberalism”. This phenomenon – sometimes called “everythingism” – is not confined to US politics. It is at least equally pervasive in British policymaking.

At its simplest, everythingism occurs when a straightforward policy goal becomes complicated by a laundry-list of secondary objectives, often without a sense of the trade-offs involved. A policy originally conceived to achieve one worthy objective, such as building more housing, becomes a vehicle for achieving a whole host of wider progressive objectives – such as unionised jobs, decarbonisation, reducing inequality, or ending car use – to the detriment of achieving any one of these goals well.

The use of government procurement to try to achieve disparate public policy objectives is a prime example of everythingism in action. On the face of it, the state should, like any other buyer, optimise primarily for cost and performance, then act decisively. There’s no intrinsic reason why the bulk of these transactions should be significantly more complicated than procurement in the private sector, where businesses also need to purchase things from suppliers.

Yet the reality is starkly different. Any government purchase over a modest threshold (around £140,000) triggers a lengthy and cumbersome public tendering process. Above £5 million this complexity multiplies further, requiring bidders to meet extensive requirements – social value contributions, climate commitments, anti-modern slavery declarations, security assurances, and diversity statements. Simplified processes exist, but in practice, they do little to ease the bureaucratic burden.

Individually, these requirements seem reasonable. Collectively, they become a straightjacket. Their combined effect is to drastically limit the pool of bidders, with the result that the government often ends up paying more for worse outcomes. Affordable and high-quality suppliers may count themselves out of public tendering, or find themselves excluded, because they do not know how to navigate the morass. Despite a stated aim to support small domestic companies, the beneficiaries of this procurement system are typically larger firms that can corner the market – not on the basis of service quality, but due to their ability to game the bureaucracy.

The lesson here is not that objectives such as sustainability, diversity, or local economic benefit should be discarded. Rather, policymakers must resist the temptation to address every desirable outcome through every mechanism at their disposal. Effective governance means identifying the right tools for each specific objective. When each lever of the state is used to address manifold problems simultaneously, the inevitable result is confusion, dissipation of resources, inefficiency, frustration, and waste.

At a deeper level, everythingism emerges from a political culture that uses coalition-building inside bureaucracies as a substitute for democratic legitimacy. Initiatives that are not clearly mandated through democratic processes (for instance, through clear public backing or inclusion in a manifesto) often seek legitimacy through the buy-in of internal stakeholders – particularly from parts of government that might otherwise compete for resources. Anxious to secure broad backing and have their ideas stand out amidst fierce internal competition, policymakers are incentivised to overstate the virtues of their proposals. Trade-offs between competing objectives are either ignored or implicitly wished away.

Coalition-building, then, becomes a necessary tool to bypass potential objections throughout the system. The more you broaden your initiative – bringing potential allies on board by assisting their goals – the greater your chance of success. But the price is ever increasing complexity, diluted focus, and endless compromise. Every stakeholder receives a consolation prize, and nobody achieves what they really need.

Once you notice it, everythingism is everywhere. Requiring pension funds to invest in British companies or environmental funds might sound like a good idea, but is this really the best way to deliver returns for pensioners, raise capital for UK firms, or protect the environment – or do you end up doing each of these less well? A (thankfully recently removed) duty for local authorities to consult Sports England before building new houses may have been well-intentioned, but was it the best way of supporting local sports facilities, and worth the cost of slowing down or preventing new house building?

Many seemingly intractable policy initiatives have in fact been kneecapped by everythingism at every level. The well-documented case of HS2’s bat tunnel – a proposed £120 million structure intended to shield bats from new high speed trains – is emblematic of this failure. Not only is the proposal exorbitantly costly as a piece of rail infrastructure, it’s also strikingly ineffective as a means of protecting biodiversity. This fiasco contributed to HS2 being delayed by four years, and costing billions more than planned, and having its northern leg cancelled.

Everythingism produces nothing. By insisting that every policy achieve many goals at once, we fail to deliver anything. The twisted irony is that we end up making everything much costlier than it should be, only to (sometimes) deliver things tangential to our primary goals, which may not have warranted anywhere near that level of intentional investment.

This mindset is in part a product of scarcity, where decision makers load more responsibility onto fixed resources. But economic growth can go a long way to solving the issue. With growth, many apparent trade-offs become softer than they first appear. Often, we do not, in fact, need to choose between two competing priorities, because growth itself creates flexibility. Prosperity and effective policy generate both the surplus resources – “headroom” – and the political latitude necessary to achieve multiple goals separately and successfully. Had we delivered HS2 efficiently and economically, the dividends could have been substantial enough to finance conservation initiatives far more ambitious – and impactful – than any single mitigation measure. Instead, we got neither HS2, nor the economic headroom to pursue other goals.

How can everythingism be avoided? To return to Klein:

Ezra KleinYou might assume that when faced with a problem of overriding public importance, government would use its awesome might to sweep away the obstacles that stand in its way. But too often, it does the opposite. It adds goals — many of them laudable — and in doing so, adds obstacles, expenses and delays.

The use of brute force is tempting. Sweeping aside obstacles that block policy implementation can be a viable option, provided the political capital spent on overcoming resistance costs less than getting people on side. But that's often not the case, as policymakers usually lack a strong political mandate for specific interventions, leaving them without the electoral legitimacy to bulldoze their way through institutional resistance. The public can grant leeway, but seldom unlimited licence to disregard legitimate stakeholder concern.

A more effective strategy is to identify concerns and potential blockers from the outset, and develop targeted ways to deal with them. For example, Natural England’s objections to HS2 stem from genuine environmental concerns. But by holding veto power without bearing direct responsibility for resolving the problems they raise, their objections become functionally unlimited in cost. Imagine instead that Natural England were granted a defined budget, and explicit responsibility for addressing environmental issues such as bat protection. They would then be incentivised to find truly cost-effective solutions, internalising the true consequences of their policy. Empowered and with real accountability, they could pursue a truly optimal solution, rather than wielding unchecked power that allows even a single objection to derail projects.

The path out of everythingism is somethingism – clarity of purpose. Policymakers should articulate clear priorities, design mechanisms and systems of accountability to address trade-offs, and create systems where responsibilities and incentives align. Rather than trying hopelessly to achieve everything at once, we should instead do one thing that is meaningful – then another, then another, until individual victories compound to build a better future.

Rediscovering Agency

If everythingism is a symptom of Britain’s institutional decay, a deeper malaise is a paralysis of agency. Over decades, the machinery of governance has been refined not for decisive action but for endless diffusion – where responsibility is everywhere yet nowhere, authority is separated from accountability, and the capacity to make decisions has become disconnected from the mandate to implement them. Politicians and civil servants alike find themselves disempowered, unable to take initiative or see policies through to successful outcomes.

This is because responsibility is too diffuse. Modern British governance is characterised by endless rounds of consultation, multiple layers of sign-off, and an expectation of broad consensus before action. What passes for thoroughness, fairness, or inclusion in theory manifests as paralysis in practice. Officials at every level find themselves trapped in webs of distributed responsibility, where the power to say “no” is widespread, but the authority to say "yes" – and make it stick – is vanishingly rare.

The diffusion of agency and responsibility creates “responsibility voids” – gaps that result when everyone has partial ownership of a problem, but no one has both the mandate and the means to solve it. The pursuit of real-world outcomes becomes secondary to the management of process.

Such responsibility voids can have dire consequences for the British people. The NHS’s outdated and fragmented IT infrastructure – split across local trusts, hospitals, and GP practices – is a case in point. This fragmentation makes data retention harder, heightens the risk of cyber attacks, inflates administrative costs, and wastes time for patients and staff alike. That our NHS IT system is so woefully inadequate and fails our healthcare workers is a truth universally acknowledged in Westminster, but attempts to fix it have failed catastrophically.

Part of the problem lies in the diffusion of accountability across the healthcare system. Though the NHS is formally a single unified national service, housed within a single government department, in practice it is a complex tangle of overlapping mandates and fragmented authority. Structural reform – particularly of something as complex as IT – requires central coordination. But in a system where responsibilities are diffuse and overlapping, where every part can resist and no part can compel, even well-designed plans unravel on contact with institutional reality.

As a result, no one was clearly responsible for delivering a transformational IT project at reasonable value for money. When the project failed, it did so without consequence for any of the individuals involved. No one at a senior level was held to account – because no one, in practice, was truly in charge.

The failure cost the taxpayer £10 billion, and was ultimately abandoned almost entirely. Patients remain stuck with an inadequate, fragmented IT system, and the money lost could have built new hospitals, or helped clear the NHS backlog.

Weak accountability and disempowerment increase the risk of disasters – from the Grenfell Tower fire (which exposed confusion over who was responsible for housing safety) to the unlawful deportations in the Windrush scandal. Inquiries into such events repeatedly find that no one felt empowered to raise concerns or take decisive action before things went wrong. And when things do go wrong, a lack of accountability and responsibility mean that it is hard to work out what happened, and how these disasters might be avoided in the future.

But when clear responsibility meets decisive authority and sufficient resourcing, we see very different outcomes. We catch rare but revealing glimpses of this in the most productive corners of science and technology – fields where, under pressure of urgency and consequence, some institutions have dared to radically experiment with organisational design. Such institutions are not the norm. Much of modern science is as constrained by risk-aversion and procedural excess as any government department. But in those cases where agency has been deliberately protected – where individuals are entrusted to lead, to decide, and to deliver – the outcomes speak for themselves.

Nowhere is this model better exemplified than in the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Since its founding in 1958, DARPA has produced a steady stream of foundational technological breakthroughs - from GPS, to the internet, to mRNA vaccines. Its genius lies not in scale but in structure: a simple but radical operating model in which small, mission-driven teams are led by empowered Program Managers. These individuals are not caretakers of consensus, but rather have end-to-end ownership of problems, with the resources to pursue solutions unencumbered by bureaucratic drag.

This model inspired the UK’s own bold institutional experiment – the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA). ARIA’s Programme Directors are charged with setting direction, deploying funds, and shepherding ideas from spark to delivery – all with minimal interference. Risk is not merely tolerated; it’s owned. Responsibility is not distributed; it’s borne. The structure insists on agency – and trusts people enough to wield it.

But to make a trial of this model feasible in Britain, ARIA had to be insulated from the rest of the government, in a way that DARPA is not. ARIA was granted wide-ranging exemptions from HM Treasury business case rules, procurement regulations, freedom of information requirements, and myriad Civil Service codes. In essence, creating ARIA required creating an ‘air gap’ from the British state - a rare, protected space where agency could thrive.

This was not reform – it was a workaround. And the need for such legislative acrobatics ought to trouble us. That ARIA had to be carved out and protected shows just how inhospitable the wider system has become for agents of empowered delivery.

How do we restore agency not in pockets, but across the British state itself? If we want individuals to act with energy, clarity, and conviction, we must grant them not just responsibilities, but the means to fulfil them. This begins with cultivating a culture of agency in our public institutions – one that rewards initiative, tolerates failure, and recognises delivery as a core public good.

But cultivating agency is not only a matter of culture, it is also a matter of architecture. Individuals cannot deliver if the system is built to restrain them. Empowering our political leaders requires confronting the institutional blockers that separate political mandates from implementation capacity.

First: too often, policymakers inherit responsibility without the resources, authority, or support to exercise it. Ministers nominally command vast departments, but they cannot hire or fire the officials running projects. The modern state has evolved layers of intermediary institutions – from arms-length bodies to international treaties, from judicial review to statutory consultations – that constrain executive action. Many of these constraints serve important democratic purposes. But their cumulative effect has been to separate the power to decide from the power to do.

Second, is the lopsided distribution of power. There are many actors throughout the system who can stop initiatives without consequence, but few who can give greenlights. Everyone holds a veto, but no one holds a mandate. The result is a system where accountability is separated from agency.

And third: in a healthy system, those with the power to act should also bear responsibility for outcomes. But in Britain today, those with the power to exert the most pressure often escape responsibility for bad outcomes, while those tasked with delivery lack the authority to make meaningful changes. Regulatory bodies have the power to impose requirements without having to deliver the outcomes those requirements are meant to secure. Civil servants can design policies that fail on contact with reality, yet face no consequences for the fallout.

What we get out of a system that disperses power, blurs responsibility, and blocks delivery, is a serious democratic deficit. When governments cannot deliver what they promised due to blockages in the system, public trust is eroded. Politics becomes increasingly performative - focused on gestures and announcements rather than tangible change.

Restoring agency in public life requires a reimagining of how decisions are made. For important decisions, it should be possible to identify who is in charge. Where possible, government should default to individual responsibility over collective process, with fewer decisions made by groups of policymakers, and fewer initiatives launched without clear ownership. Power cannot be held to account if it cannot be located.

We also need to reduce the number of veto players. Those who wield the power to block or delay critical projects should bear some of the costs when projects stall. Regulatory bodies should be evaluated not just on process compliance, but on outcomes. The Government has rightly watered down the duty for councils to consult a whole host of external agencies when planning new buildings, ranging from Sports England to Theatres Trust. Reducing the number of veto players helps concentrate power where it is most needed and most accountable.

Britain needs institutions that possess the agency to set clear direction and marshal resources to meet the moment.

.jpg)

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Salisbury’s 800-year-old cathedral was used as a vaccination centre (2021) | licensed from Alamy

We have seen recently how this can work in modern Britain. During the COVID pandemic, Kate Bingham, Chair of the Vaccines Taskforce, was given real authority, political backing, and the resources to move at speed. Veto players were successfully sidestepped. The result was life-saving, and Britain led Europe in procuring and deploying vaccines. But this was an exception born of national crisis: once Covid had passed, the system reverted to type – diffuse, over-cautious, and stuck.

The challenge of agency is not merely technical or organisational. It is fundamentally about courage - the courage to take responsibility, to make decisions under uncertainty, and to bear the consequences of both failure and success.

Rage Against the Machine

The machine of government is broken. For many, the experience of government is one of permanent dysfunction, where nothing works, and the system is unresponsive. Frustration is mounting across the country – and rightly so. Britain’s stagnation is a scandal that warrants deep dissatisfaction, and impatience with the status quo is a necessity for radical change. The need for disrupters has never been greater. But how should we drive these revolutionary reforms?

Since its emergence in the 19th and 20th centuries, the modern administrative state has time and again become the target of attacks from across the ideological spectrum. From wholesale condemnations of the “deep state” to populist insurgencies promising to return power directly to the people, bureaucratic institutions have continually faced fierce, often well-deserved scrutiny.

Across the Western world, there’s a growing hunger for a type of regime change defined by rapid, indiscriminate destruction – a ‘burn it down’ impulse that is most evident today in the United States, but is also beginning to find expression in Britain. It is often rooted in sound diagnoses of the many maladies ailing the public sector. But that frustration can fester into a politics of demolition that offers no true solutions: deepening social divisions, cutting allies loose, and dismantling, not reforming, the institutions of progress.

.png)

J.M.W. Turner’s “The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons” (1834) | public domain via Google Art Project, Wikimedia Commons

To reveal the hollow promise of such movements, we need only examine their theory of change. It is true that you can squeeze a burst of energy out of an ossified system by dismantling programmes, indiscriminately deregulating, or tearing down institutional guardrails. Smashing things up can briefly create room to manoeuvre.

But such an approach quickly reveals itself as empty. Behind the veil of state reform lurks vindictive nihilism – a burning desire not to build for the benefit of the country and its people, but to tear down, to humiliate, to exact revenge on the bureaucratic elite. It is far easier to destroy than to create. Destruction is easy; creation takes courage.

Champions of this style of politics on both sides of the Atlantic have proven unwilling or incapable of constructive engagement. Instead, they resort to ‘troll epistemology’ to malign opponents. They speak with condescension about those they perceive as hostile, dismissing them as ‘Non-Player Characters’ or mindless apparatchiks in thrall to the bureaucracy. Styling themselves as the new ‘cognitive elite’, they refuse the basic political responsibility of persuasion.

The result of all this hostility is to amplify broad resistance, and poison the project of reform. Rather than recognising that many within the state apparatus are equally dissatisfied with its processes and outcomes, and inviting them into the tent, potentially indispensable allies are deliberately antagonised. This politically reckless behaviour may satisfy an impulse, but achieves little beyond temporary disruption and long-term hostility.

Politics fuelled by resentment is inherently unsustainable. It is cathartic but not constructive. Its adherents loathe the managerial elite so intensely that they cannot distinguish between legitimate critique and crude caricature, conflating incompetence with conspiracy and institutional disempowerment with moral corruption. Such movements burn brightly, but briefly, leaving in their wake little more than bitterness, suspicion, and a legacy of political dysfunction that serves as a lasting gift to precisely the “elites” they despise.

When these campaigns collapse, their proponents will have exhausted the political capital and goodwill required for genuine reform. This can create counter reformation, to protect the status quo. Those who emerge to take the reins might seek to distance themselves from the spectacle of recklessness, installing even more safeguards and processes that threaten to further choke the engines of material well-being in this country.

The establishment may find it easy to paint reform itself as dangerous extremism. And it would be ordinary people who suffer, as the comprehensive restructuring (and its fruits: growth, and prosperity) that was promised fails to materialise. To fail in this way is to risk leaving the future of Britain in the hands of those who reject the project of progress entirely.

There is a better way – radical but disciplined, bold yet grounded. We must acknowledge the grand scale of the challenge without descending into nihilism or revelling in recriminations. True reform requires having the confidence to bring people along with you, identifying potential allies within the system, and offering people pathways out of dysfunction, not into resentment. It means strategically redistributing power to the people and institutions best placed to use it effectively, dismantling only what is genuinely obstructive or redundant, and finding creative new paths forward. It means distinguishing legitimate bottlenecks from vexatious complaints, engaging seriously with the former while confidently dismissing the latter.

We must inspire with visions of a better future, grounded in optimism, not grievance, and capable of building sustained support. This is the only way to create a lasting blueprint for systemic upheaval. The future of Britain should be shaped by those committed to delivering progress for all of its people. If this requires restraint and respect, it is not a compromise but a foundation – one that makes real reform not only possible, but enduring.

Our approach does not deliver the immediate catharsis of rage. But unlike rage, it is capable of delivering progress.

Why We Set Up the Centre for British Progress

The true power of progress lies in how we choose to shape it. Our history shows this. As Britain industrialised and grew wealthier, we used the fruits of that growth to build a system of universal education – freeing millions from illiteracy and opening the door to discovery, invention, and ambition. This was not an inevitable outcome of prosperity, but a conscious decision to turn economic power into social progress. Growth provided the means; politics provided the will. Today, new technologies offer glimpses of how the boundaries of learning can be pushed further.

Material progress can, if married to the right political choices, give time and space for humans to pursue new forms of creativity and quests for moral fulfilment. Our politics, constrained by the logic of zero-sum scarcity and managed decline, could become an ambitious project of collective action. The social and political reforms that defined the last centuries could find new expressions on these islands.

We are launching the Centre for British Progress because we want to build the future in Britain. A future where progress delivers abundant possibilities for our people. We imagine a future of technological advancements that liberate us to pursue lives of security and meaning: where diseases are cured, electricity is clean, cheap and reliable, where work is creative and meaningful. The halfpenny postcard transformed communication and catalysed progress. This same catalytic potential lies dormant in the technologies of our age: delivery drones could bring life-saving care to the furthest corners, water treatment systems could banish toxins like lead from every tap, and abundant, clean energy could make a warm home a universal right – not a privilege – for every British family.

For our economy to become more dynamic, we need a dynamic policy environment. It is easy to blame Britain’s leaders for its decline, but government policy can only be as good as the ecosystem on which it depends: the network of ideas, talent, and institutions that not only craft concrete policy proposals, but also define the boundaries of our policy ambition.

We launched UK Day One in 2024 as an election year project to help the new Government pursue implementation-ready policies for growth. ‘Day One’ describes not only the day after the election, but also a mindset and practice of constant reinvention and improvement. Over the past year, we have had the privilege of helping to shape the new Government’s policies – from Heathrow and planning reform to AI strategy and nuclear energy.

We quickly became convinced that there is a more fundamental gap in Britain’s policy ecosystem. Although there is a growing pro-growth coalition, and clear demand for pro-growth ideas from this Government, there remains no progressive organisation that is focused on policies for British growth; no organisation founded with an explicit understanding that economic growth must be harnessed for the material and social well being of the British people. The Centre for British Progress will occupy this space. Our aim is to understand the barriers to growth in the UK and find ways to overcome them. While this essay outlines some initial diagnoses and potential solutions, the real work begins now.

We care about growth not in spite of being progressives, but because we are progressives. In this regard, we stand in a long tradition of British social reform. In 1942, a pivotal year of the greatest war Britain has ever fought, William Beveridge declared war not on fascism or a foreign power, but on the “Five Giant Evils” of poverty, disease, ignorance, squalor and unemployment.

Today, as conflict and populist forces once again threaten the stability of the world Britain helped to build, Britain must draw on this reforming spirit. Instead of conservatism, we must choose dynamism. Instead of borrowing, building; and instead of impotence, courage. Growth allows us to expand our collective horizons and build a better society for all. Britain can be a place where anyone, whatever their background, is empowered to build their future on these islands, each generation more confident, creative and prosperous than that which went before.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Pedro Serôdio and Nick Garland for helping to develop many of the economic arguments that formed the basis of this essay, Freddie Poser for designing the graphs, Maxx Turing for keeping everything on track, Andrew Bennett for his taste, Tom Blake for research and fact-checking, and our many reviewers and feedbackers, particularly Hannah O’Rourke, Morgan Wild, Samuel Hughes, John Myers and Jack Wiseman.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]