Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Context and challenges

- 3. Solutions

- 4. Authors

- 5. Acknowledgements

Summary

Britain doesn’t need a bonfire of its quangos. It needs a controlled explosion.

Today, our two types of regulators face crippling challenges hindering growth and progress:

- Economic regulators, in sectors like energy and water, are failing to enable growth: we face regulatory bloat without improved outcomes, delayed investment, ineffective competition enforcement, eroded state capacity, and zombified private operators as they and regulators alike creak under the weight of ever-growing duties and regulations.

- Safety regulators, in sectors like nuclear or medical devices, are failing to accelerate breakthrough innovations: creaking regulatory capacity is constraining economic and startup growth, slowing innovation in the markets that need it most, and limiting the highest-productivity sectors of Britain’s economy.

The government has recognised that things need to change. Yet initial, tempting fixes are flawed:

- A ‘bonfire of quangos’ risks being indiscriminate and chaotic, while creating an awkward precedent for any new public bodies that do need to be created.

- ‘Red tape challenges’ of old have been ineffective, focusing solely on erratic deregulation instead of fixing structural challenges with incentives and capacity.

- There is limited space to raise infrastructure investment by passing the cost onto consumers, when bills are already high.

- Reversing the scope creep of regulatory objectives is the right instinct, but the constant ratchet of duties and expectations reflects real societal goals that can’t just be abandoned. Sectoral regulators will always have an incentive to prioritise consumer protection.

For some, the original sin was the privatisation of utilities. This created the need for regulation because the state was no longer internalising economic and social trade-offs via nationalised operators accountable to democracy. While major successes under nationalisation are often underrated – nuclear, the grid, hydro and gas networks – this model also gave us British Telecom and British Rail. Meanwhile, despite the challenges of privatised utilities, drinking water quality has improved, power cuts have decreased, and it is startups – the delivery units of progress – inventing small modular reactors, energy flexibility and satellite internet.

Focusing exclusively on ownership is a red herring. Instead, we must fix the regulatory state to support agency and delivery at scale by unblocking our most innovative organisations – engines of abundance both public and private – and reigniting economic dynamism.

To that end, we propose two major institutional reforms to solve each of our economic and safety regulator challenges:

- Begin scrapping sectoral economic regulators, splitting their policy, regulatory and delivery functions between re-empowered departments, a newly expanded CMA, and new/existing System Operators: starting with Ofgem and Ofwat, repatriate policymaking to DESNZ/Defra and merge economic regulatory functions into an expanded, politically-independent CMA to enforce competition and consumer rights across the economy (with appeals processes moving to the Competition Appeal Tribunal). Eliminate or split any remaining functions between specialist, technical safety agencies, e.g. the Drinking Water Inspectorate, and delivery-focused ‘system operator’ bodies, akin to NESO in energy. The government should also use its ongoing quango review to assess if the economic functions of other ‘economic regulators’ – Ofcom, Office for Road and Rail, the Financial Conduct Authority, and the Civil Aviation Authority – should also be merged into the CMA.

- Establish an Accelerated Innovation Agency (AIA) on a statutory footing — a new, cross-sectoral, ‘n+1’ innovation regulator — to inject pace and urgency into bringing critical innovation to market: Sectoral safety regulators have become a blocker on frontier technologies that could bring critical competition and innovation to sclerotic markets, such as nuclear energy, drones and healthcare. A new cross-sectoral agency would have a different incentive structure, pooling the risk appetite across sectors with a singular focus on accelerating innovation. Unfortunately, the Regulatory Innovation Office already appears dead on arrival, with no authority, money, or power to influence departments or regulators. Either it needs a turnaround, or the government must cut its losses and start again.

The net effect of these changes would be enormous.

Abolishing prescriptive sectoral economic regulation and ‘just one moreism’ – where politicians and sectoral regulators are incentivised to add new duties and rules, undermining predictability and investor certainty – in favour of ex post competition and consumer rights enforcement will support competition, business dynamism, and investment. This would also provide less of a ready-made vehicle for ad hoc political interventions, reducing the flow of new regulations, while re-empowering the consumer voice against highly organised sectoral incumbents.

A new Accelerated Innovation Agency would expedite the route to market for breakthrough innovations, boosting startup and economic growth in the UK, and provide a competitive check on existing, sclerotic safety authorities.

Moving to this structure would be radical for Britain, but not internationally, with similar models existing in the Netherlands, Australia, Spain, and elsewhere. The government’s current regulatory action plan was a start, and its Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce is even more promising. But marginal tweaks won’t lead to a step-change in outcomes. The monumental decision to scrap NHS England – in that case returning its functions to DHSC, although here the independence of economic regulatory functions must remain paramount – proves it has the courage required for bold reforms.

Sectoral regulators and some anti-innovation, incumbent private operators who are content with regulatory capture and rent-seeking will likely resist these changes. The main objections will centre on the risk of political interference and the uncertainty from institutional disruption. Both can be dealt with:

- A strong commitment to regulatory independence in the new landscape is critical to assuage concerns of political interference: The government must clarify that while the policymaking functions of sectoral regulators should return to Minister-led departments, economic regulatory functions should remain independent in the CMA. Independent decision-making could also be empowered with greater transparency, for example by moving from our current governance model based on a Chair and Non-Executive Directors to a 5-person Commission that makes decisions. This change would make it harder for any single actor, political or private, to exert undue influence.

- These reforms will simplify a broken status quo hindering investment, despite short term disruption: As the NAO has documented in water, the current sectoral pricing model is complex for investors and leads to cyclical spending with delayed infrastructure delivery. The status quo is already failing: claims that re-organisation will hinder, not help, investment should not be taken at face value. Meanwhile, the new structures should be set up quickly to be in place and trusted well ahead of the next pricing reviews.

Finally, to make this work, several additional steps will be required:

- Both the CMA and sectoral system operators must become truly digital organisations to fulfil their expanded new consumer-facing and system-orchestrating roles: as the founders of the Government Digital Service once defined, this means “applying the culture, processes, business models and technologies of the internet-era to respond to people’s raised expectations.” The CMA should organise itself around consumer needs and build services to support rights enforcement. Similarly, NESO and other system operators should have deeper data capabilities both to model the energy network in real-time and deliver consumer-facing smart data infrastructure, potentially paving the way for auto-switching tariffs and the dissolution of retail price caps.

- Refocus system operators on accelerating infrastructure delivery by promoting contestability, not central planning: The system operator model offers a great opportunity for the government to show it can rebuild state capacity in critical sectors, but early signs from NESO suggest it still needs work. Despite NESO’s ‘control room’ roots, system operators must not assume the role of central planners and gatekeepers. Instead, they must focus on contestability and encourage competitive pressure throughout the infrastructure stack. It should support third parties to construct new transmission projects, and to originate, finance and operate entire projects to accelerate new network capacity without adding pressure to consumer bills.

- After institutional rationalisation, improve regulatory pay, incentives, and accountability structures: Consolidating expertise in a combined competition and consumer regulator should allow for fewer but higher quality and better-paid staff. This would attract private sector experience into regulators, which is critical to discriminate between, for example, when regulated utilities achieve genuine efficiencies or underperform. Similarly, a unified economic regulator could be sponsored by a single department – HMT, to match the CMA’s expanded power – providing stronger strategic oversight than today’s variable, duplicative and uncoordinated multi-departmental model.

- Establish a zero-based, ten-year review cycle of every regulator and rulebook: Rather than bemoaning the constant ratchet of regulators and regulations, we must accept it is an emergent constant in a democracy. We must instead build in regular correction mechanisms and a durable capability to prune regulatory creep, instead of relying on erratic, ad-hoc campaigns.

Context and challenges

Regulatory bloat without improved outcomes

After privatisation, regulators started with minimal duties. Over time, these have grown and become a straightjacket.

Take Ofwat: It now has 6 primary statutory duties, 6 secondary duties, 4 ‘strategic priorities’ and, according to the 2022 strategic priority statement, at least 53 formal ‘expectations’ set by Defra.

In 2024, Ofwat, Ofgem, and Ofcom took on a new duty focused on economic growth. This may have some marginal impact, by now encouraging these regulators to consider growth, but is easily abused: existing work can be rebadged and bad proposals can be revived by making them look good under the BCR microscope. In practice, the net effect is little change in behaviour beyond further administrative burden and the constraints of ever-growing regulatory duties simply being transmitted onto regulated entities, who then have little surface area over which to differentiate and compete.

We have hollowed-out state capacity and zombified privatisation, instead of high-capacity states and high-agency, dynamic market operators.

Price controls incentivise capex underspend over abundant supply

In our core utilities markets, pricing models have focused on keeping consumer bills down, prioritising efficiency savings and asset-sweating over capital expenditure.

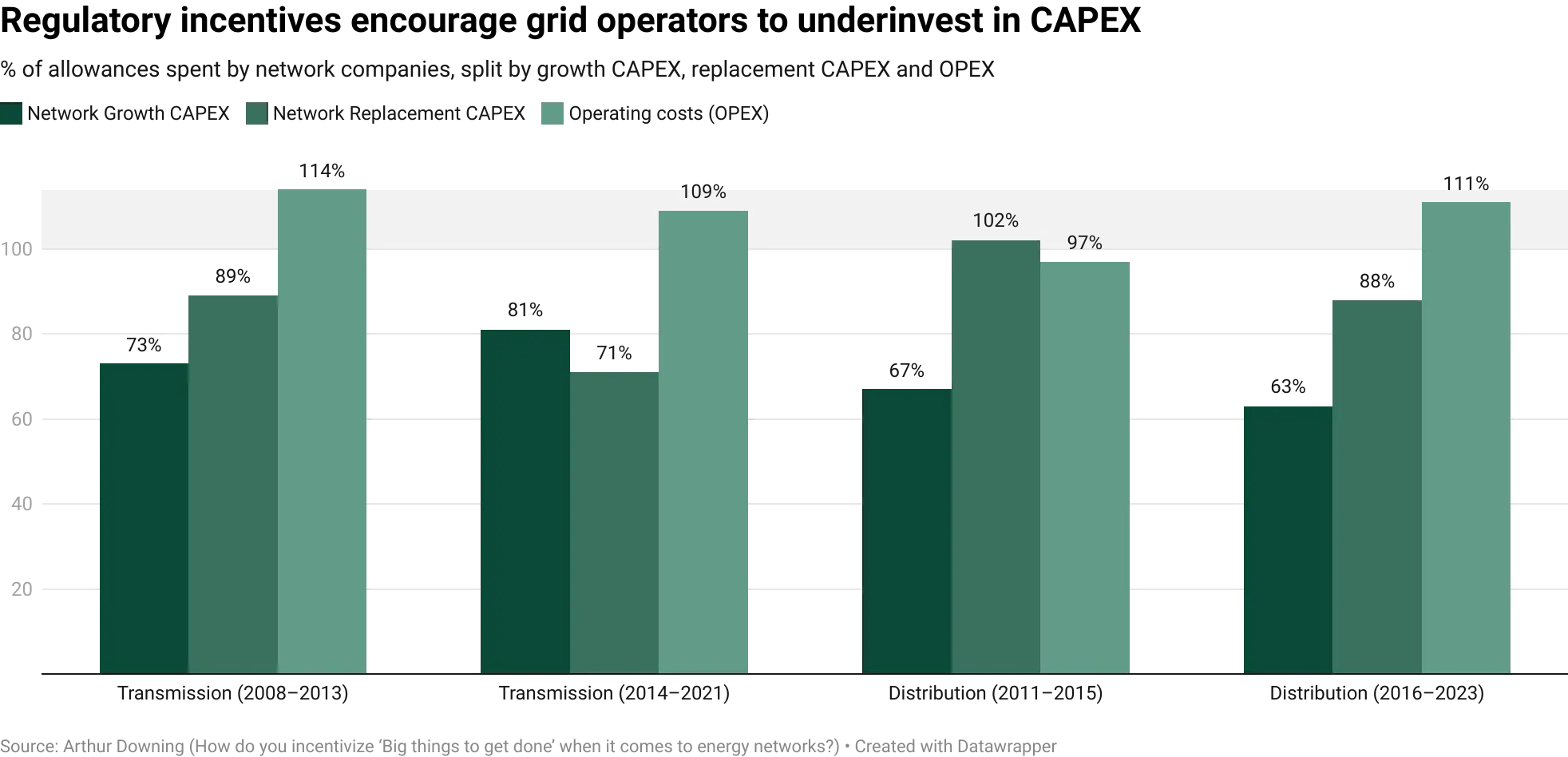

In energy, the RIIO (Revenue = Incentives + Innovation + Outputs) model works by companies estimating investment needs for outcomes (e.g. replacing assets or upgrading capacity), with Ofgem scrutinising and agreeing a (usually lower) level of ‘baseline allowances’. To incentivise efficiency, RIIO contains a mechanism whereby networks that spend less than the allowance can keep some of the difference, to mitigate against overcapitalisation and building useless assets. But in practice, as Arthur Downing shows, RIIO has consistently incentivised underspending on capex.

This doesn’t mean networks haven’t achieved their outcomes – which may be achieved by other means (e.g. efficiencies, innovation, customer deferrals or revised requirements).

But it illustrates our lack of ambition. The mechanism misframes the question, asking “for a low return, how much investment can you make?” Efficiency matters so consumers don’t overpay. But amid huge infrastructure need we currently don’t need to worry about overcapitalisation. A pricing framework that incentivises under-investment of capex – asset sweating instead of asset building – falls short of what we need to support growth.

A similar model exists in water, with similar results. Only recently, the NAO stated:

“Defra and the water sector’s regulators have not encouraged water companies to spend what they need to deliver the performance expected. The sector now faces significant environmental and supply challenges. To meet these challenges, it will need to attract investment and spend at a rate not seen before.”

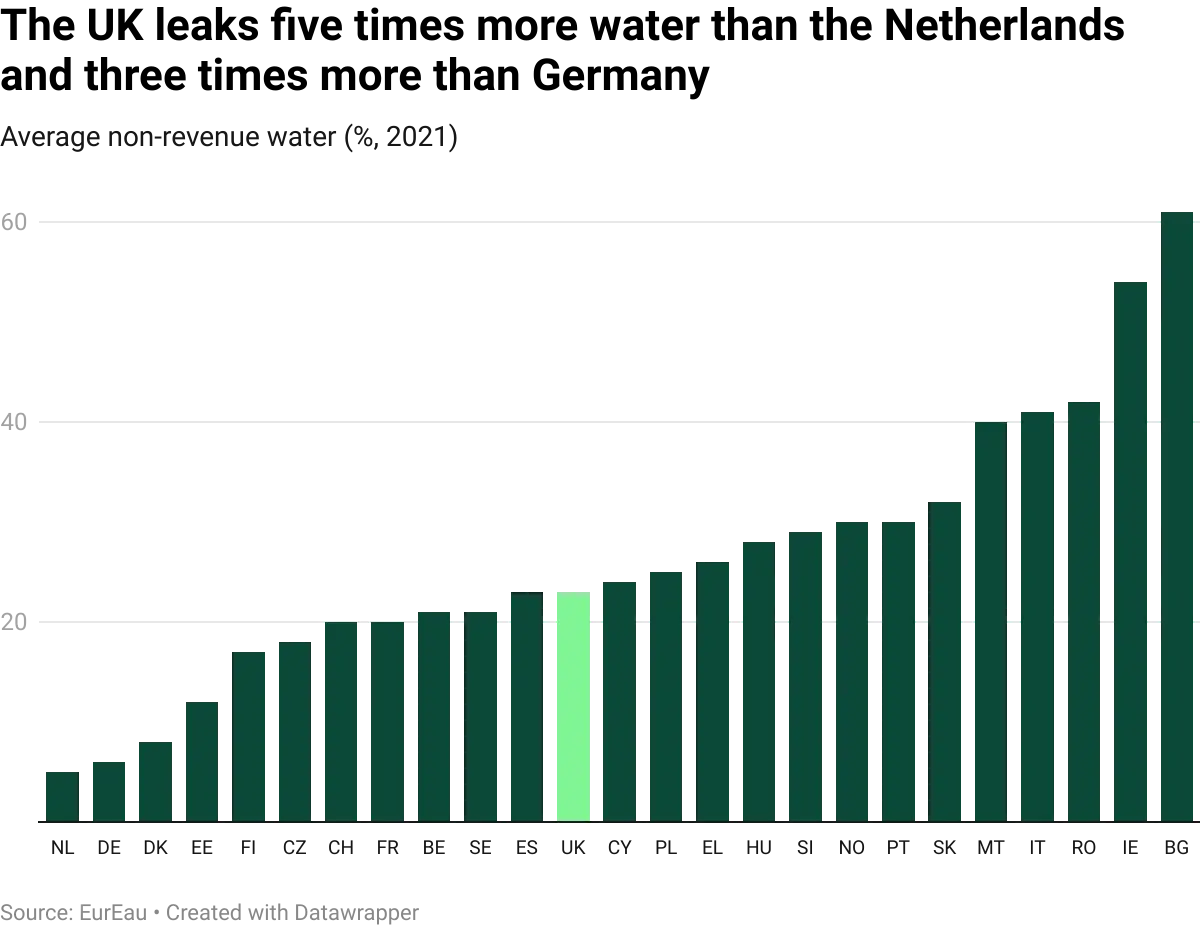

Despite our regulatory model promoting asset-sweating, there’s still enormous inefficiency in water. Around 21% of our supply – 3 billion litres – is wasted daily due to leakage. This is partly because companies don’t even know where all the pipes are, let alone which are leaking – an environmental issue as much as an infrastructural one. Although leakage reduction improved post-privatisation, it has remained flat over the last 25 years. Water has near-zero marginal costs, but the cost of leakage adds up. Shortfalls are a major bottleneck on an abundant future: while reservoirs are necessary they are slow and expensive to build, so leakage reduction is important for meeting rising demand quickly.

Reducing leakage to Dutch levels (about 5%) would save 839.5 billion litres of water yearly. This is equivalent to building nearly 6 more Abingdon reservoirs, each holding 150 billion litres, and would meet nearly half of the NAO’s projected 2050 shortfall. In practice, we’re unlikely to reach that threshold because places with leaks won’t perfectly overlap with places with water shortages. But we don’t know, because we don’t know where the leaks are.

This isn’t about reducing demand, but capturing maximum throughput of existing supply. And it is solvable: companies like Xylem, Pipebots, and Datatecnics are bringing solutions to market.

Yet procurement from water companies remains a huge barrier. Regulated operators lack the capability or incentive to invest in core ‘capital maintenance’ or breakthrough technologies. Despite a recent shift towards longer time horizons, Ofwat’s pricing reviews have focused on 5-year Asset Management Periods (AMPs) misaligned with the decades-long lifecycles of critical infrastructure like pipelines, pumps, and treatment plants. Coupled with slow meter adoption and a regulatory focus on cost efficiency – where regulators approve investment plans and effectively decide which solutions can be procured – there is little incentive to make long-term commitments to find and fix leaks. Although Ofwat has established a £200 million Innovation Fund, this is subscale to shift water company incentives and stimulate a market for water-tech companies – dampening outside investment – and is negligible relative to the £290 billion of infrastructure investment required over the next 25 years. Ofwat and water companies rely on external consultants, lacking in-house digital and technical capability to explore novel solutions. Collectively, this is a recipe for stagnation.

Instead of fixing this broken system, Defra’s recent water management resource plans rely on demand reduction to “address over 65% of the supply demand balance deficit across England.” There’s a case for some demand management – 40% of households still don’t have meters, so feel no billing incentive to manage usage – but focusing so strongly on it is a degrowth premise. To grow, we need more housing, datacentres, and other major developments – all requiring water and energy. Focusing on demand reduction bottlenecks these projects. We must break free of assumptions which embed stagnation.

Regulatory structures and incentives encourage risk-aversion and delivery failure

In water, Ofwat, the Drinking Water Inspectorate, the Environment Agency, and Natural England have conflicting responsibilities. Yet, the NAO states: “None...have a duty to ensure there is a coherent national plan for the water sector. Despite increasing pressures on supply and unprecedented investment in new infrastructure, there is no coherent national system where integrated decision making can take place”. So although the sector doesn’t have to deal with a single, national grid queue, planning is still a problem. In 2011, the Environment Agency blocked Abingdon reservoir citing “no immediate need”. Now, the NAO estimates a “shortfall of nearly 5 billion litres of water per day is expected by 2050, based on current usage rates. This is more than a third of the 14 billion litres currently used daily.”

Similarly, nuclear projects require 6 points of expensive, time-consuming approval (local planning, ONR, Environment Agency, Defra, DESNZ, and ultimately Treasury). There is no “positive force in the system to push back against time delays and cost increases,” as Jack Wiseman describes. Nuclear regulation is also based on the principle of reducing risk to “as low as reasonably achievable/practicable” (ALARA/ALARP). While sensible in theory, in practice it creates a one-way ratchet: any improvement that could make nuclear cheaper – like better technology or efficiencies – gives regulators space to demand stricter measures beyond scientific necessity, like driving radiation limits to levels orders of magnitude below safe thresholds. Instead of making nuclear more competitive – generating enormous climate and safety spillovers – innovation just resets the bar, keeping costs high. As such, while the world has built 176 reactors since 1990, the UK has decommissioned 30 but built only 1.

The same is true in other sectors. As John Fingleton highlights:

If you’re the Civil Aviation Authority and you’re thinking about drones, you have one job – keep airplane passengers safe and keep cost down. Against those objectives, banning drones makes a lot of sense – or at least banning drones out of line-of-sight, or anywhere near an airport – because while the wider benefits accrue to others, the risks are very much owned by the regulator.

Drones are crucial in the AI economy: we need a reliable regulatory pathway for flying ‘beyond visual line of sight’ (BVLOS) as soon as possible. Similarly, the Financial Conduct Authority is overly focused on short-term harm reduction, responding to issues with new conduct regulations and duties that raise barriers for innovative firms likely to improve consumer outcomes in the long run.

Across the board, the cost of foregone innovation is externalised by regulators, but socialised by us all. The status quo is curtailing our stake in the future, so we must change it.

Individual authorities bear responsibility, but the deeper problem is structural. The institutional landscape naturally produces sclerosis and vetocracy, rather than high-speed, at-scale delivery. Caution is compounded by resource constraints: for regulators, it’s easier to delay or deny progress if you have limited technical capability or manpower. When startups seek guidance or permission, public bodies often lack the authority, incentive, or accountability to do anything but pass the buck.

We need to remove the institutional blockers and ensure any remaining or new bodies operate in a different, proactive mode. Different results are impossible within this same structural arrangement.

Shared competition enforcement between the CMA and sector regulators is failing

Under the ‘concurrency’ model, the CMA and other sector regulators share competition enforcement powers. By norm, the CMA defers to sector regulators, trusting their industry expertise to decide when intervention is needed.

In reality, the original sin of concurrency is that sector regulators are competition judges, policymakers, and gatekeepers for new entrants all at once. This combination creates perverse incentives and flawed judgments.

Take the Financial Conduct Authority. After taking more than 4.5 years, the FCA eventually concluded a market study into the credit information market, finding it highly concentrated among the three major credit rating agencies (Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion). It also recognised this concentration as a barrier to broader regulatory goals, such as achieving real-time insight into consumer vulnerability. At present, lenders rely on the CRAs’ decades-old, COBOL-based infrastructure so can only work with 30+ day old data to make decisions.

Instead of encouraging new firm entry to modernise the market, the FCA introduced a new ‘designation’ scheme imposing new requirements on the big three and their customers. Many challengers warned that ‘designation’ may create a higher regulatory threshold, entrenching incumbents and stratifying the market beyond the existing requirements for new firms. Yet the FCA replied: “We are not convinced that a designation scheme would entrench the position of the 3 large CRAs. Their position, in our view, is already established, and competitors currently seek to complement the services provided by them rather than compete against them.”

This reveals remarkable fatalism. The FCA’s resignation to concentration is circular at best and self-fulfilling at worst, as it is both the arbiter of new firm entry and the judge of market competition. It is also inappropriate for the FCA to speculate on competitor strategy: in many markets, but especially where there is concentration, new entrants typically offer ‘wedge’ products to win early customers before moving onto core products. Regulators should be enabling that growth, rather than assuming that challengers who are not yet competing head-on don’t plan to and never will.

The CMA did recently review concurrency and argued it should continue, but there were several limitations:

- The review only focused on how the CMA and sectoral regulators share competition powers specifically, not how sector regulation is working in general.

- To that end, although it was beyond the review scope, the CMA did say it had “become concerned about too artificial a separation between competition concurrency and how [it shares] responsibility with sector regulators for consumer protection. There is a critical interdependence between effective consumer protection and effective competition.”

- It should “dial-up [its] cooperation with sector regulators when looking at competition and consumer issues…especially in the context of the new Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act (DMCCA) which will make major reforms to how consumer protection laws are enforced across the economy.”

In effect, the CMA review focused on a narrow question and gave a narrow conclusion. The government should take a broader view. Stuart Hudson, former CMA Senior Director of Strategy, argued the CMA’s stronger consumer protection powers under the DMCCA may now obviate the need for sectoral regulation. He argued that “a review should be conducted of how far it really remains necessary for each sector regulator to impose its own additional sets of rules and licences on those companies in its sector that are competing in a market”.

Hollowed out state capacity and Ministerial accountability

The FCA example illustrates the challenge for Ministers who often lack the powers to respond to public concern. As HMT officials work to regulate Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) firms, they rely on the FCA to deliver reforms to modernise the credit information market: the lack of real-time data hinders lenders from spotting vulnerable consumers who may stack up multiple loans quickly.

It’s an example of three failure modes of sectoral regulation hollowing out state capacity:

- Cases where Ministers are accountable but impotent: As with BNPL, Ministers are routinely held responsible for sewage spills, train delays, and other visible issues yet have limited scope for impact beyond asking the Environment Agency or Office for Rail to act.

- Regulators straying into political territory: Ofgem’s proposal to charge higher-income households more for electricity – when the principle and methodology for any redistribution should be subject to democratic accountability – illustrated this recently.

- Ministers outsourcing political decisions to regulators: Successive governments have created new regulatory regimes and arms-length bodies to ‘do something’ about a visible issue, crystallising a political discussion at one point in time into an everlasting enforcement regime. Sometimes the rationale is understandable: in online safety, Ministers wanted to avoid the charge of political interference in online speech. But outsourcing the framework to unelected Ofcom officials is no better solution. Controversial political decisions may be defensible, but they should be reversible. This is the core feature of democracy.

The government’s quango review aims to bring “ministerial, elected scrutiny back to major decisions that affect the public.” This is laudable and should bring clarity and accountability to decision-making. But it will also require courage.

Creaking capacity at innovation regulators has become a rate limiter on growth

Today, when it comes to innovation, nearly every safety regulator is struggling with one or more of the following issues:

- Resource (e.g. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, Food Standards Agency): Many regulators are now creaking under the weight of both increased responsibilities post Brexit (without commensurate funding increases), as well as the steeper learning curve presented by the very frontier, emerging technologies that could enable breakthrough social and economic progress.

- Rules (e.g. Office for Nuclear Regulation, Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority): Other regulators are constrained by the rules they operate within, waiting on investment of scarce ministerial and parliamentary time to update archaic rulebooks for the modern day or to design entirely new frameworks for novel issues.

- Risk appetite (e.g. Financial Conduct Authority, Civil Aviation Authority, Office for Nuclear Regulation): These regulators lack the appetite, ambition, culture and incentive to enable new products, frequently relegating their ‘competitiveness’ and/or ‘growth’ objective as secondary to that of consumer protection. Delaying and denying innovation becomes the path of least resistance, in order to ‘protect consumers’. But this binary, trade-off framing is flawed: short-term conservatism ultimately leaves consumers worse off, curtailing the competition and innovation required to unseat inefficient, legacy incumbents.

Regulated markets are markets that matter. So fixing these issues is essential to enable innovation where it most improves people’s lives. Startups are not arms of the state, but they are, in effect, the delivery units of progress: small, tightly coordinated teams that can have an outsized impact on the world. Unlocking this breakthrough potential must be a priority for the government. While we cannot compete on market size or government subsidy, Britain can be the best place in the world to build, test and bring products to market. For all the appropriate focus on other inputs to innovation – such as capital, talent, and spinouts – creaking regulatory capacity has now become a bottleneck on the entire innovation ecosystem.

Solutions

Move away from sectoral economic regulation: split policy, regulatory, and delivery functions between departments, the CMA, and system operators

This report shows that the sectoral regulatory model incentivises ‘just one moreism’: when a new issue arises, regulators add more rules to licensing conditions and politicians add more objectives to regulators. In turn, growing regulation increases barriers to new firms entering the market, resulting in weak competition, minimal business dynamism, and delivery sclerosis. This model cannot be saved.

The government should kickstart the move away from sectoral regulation and focus on cross-sectoral competition and consumer rights enforcement. John Fingleton, the government’s newly appointed lead for the Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce, has argued:

The trend towards sector-specific rules is understandable, but the more we go down this path the more we get incumbent capture, with regulations only understood by experts. Instead, stronger and more consistent consumer rights would support people but also make it simpler for companies bundling multiple regulatory permissions or moving across different markets.

This simplification is necessary. The NAO highlighted in its recent report on water that the complexity of sectoral regulation has become a barrier to investors and delays project delivery:

Investors told us they found the complexity makes the process hard to understand, and they focus their attention on financial performance metrics. Some companies wait until the planning process and the price review are finished to finalise their funding or operational plans. As a result, company capital expenditure has tended to follow a cyclical pattern within each price review of first increasing and then decreasing, with knock-on effects for delivery of work.

The NAO report found “a perceived decline in the stability and predictability of the [sectoral] regulatory framework.” Yet stability is the linchpin of privatised utilities: predictability is essential for companies to raise large sums of private capital at low cost. Otherwise, creditworthiness drops, the cost of debt rises, and the higher costs are passed on to consumer bills. While a significant overhaul of regulatory institutions would inevitably cause some short-term disruption, the sectoral model has reached its limits and is already failing to deliver the stability needed for long-term investment.

A streamlined, consolidated framework based on economy-wide competition and consumer rights enforcement is now warranted. Today, regulators’ default response to issues is to add extra conditions to ex ante, prescriptive sectoral licences. These licences continue to expand, leaving little room for private companies – especially lower down the infrastructure stack – to differentiate or focus on profiting by improving customer outcomes rather than rent-seeking.

Instead, a regulatory model focusing on ex post competitiveness and consumer rights enforcement would be less prone to sectoral regulatory capture, yet protects consumers while enabling differentiation and dynamism. This model isn’t dogmatically ‘deregulatory’ – it’s already the default for other issues with clear public impact like petrol prices – but can provide a simpler, more consistent framework across sectors for consumers, operators, and investors. Moving to a cross-sectoral competition and consumer approach would rebalance the interests of consumers over highly organised producers who can easily capture sectoral regulators, delivering visible, tangible benefits to everyday people.

This shift might be radical for Britain, but there are many international precedents. In 2013, the Netherlands dissolved its sector-specific regulators for energy, telecoms and consumer affairs and merged them into the Autoriteit Consument & Markt (ACM). The ACM became the sole authority for competition and consumer protection across the economy, eliminating duplication between agencies. Policymaking reverted to the relevant ministries, while independent system operators like TenneT (electricity) and Gasunie (gas) managed critical networks. Australia, Estonia, New Zealand and Spain have also integrated their competition authorities with sectoral regulators or located regulatory responsibilities within the competition agency for consistent enforcement.

The government should start this restructure by scrapping Ofgem and Ofwat and splitting their policy, regulatory and delivery functions between DESNZ/Defra, the CMA and NESO/a new water system operator respectively (see below). Ministers should also use the ‘quango review’ to consider consolidating other economic regulatory functions of the other ‘concurrency’ regulators — Ofcom, the Office of Rail and Road, the Financial Conduct Authority and the Civil Aviation Authority – within this newly empowered cross-economy competition and consumer enforcement body.

Regulatory responsibility | Typical activities today | Future vision | |

|---|---|---|---|

Ofgem | Ofwat | ||

A. Policy making | Drafting or updating rulebooks and setting sector strategies, but outside departmental accountability | → Return to DESNZ / HMT | → Return to Defra / HMT |

B. Competition enforcement | Market studies, antitrust cases, merger control | → Merged CMA, which expands to take on energy expertise | → Merged CMA, which expands to take on water expertise |

C. Consumer protection & conduct | Fair-trading rules, retail licensing, redress schemes, price-cap policing | → Merged CMA | → Merged CMA |

D. Price controls | Price controls (RIIO, PR24), cost-of-capital reviews, licence conditions | → Merged CMA consolidates expertise for pricing reviews; aim to dissolve retail price caps over time via tariffs based on smart data | → Merged CMA, consolidated expertise for pricing reviews |

E. System operation & infrastructure delivery | - Balancing the grid, running settlement systems, maintaining open technical specs/APIs - Network development plans, tendering new connections, contestability regimes (IDNO/CATO) | → NESO, promoting contestability to speed up infrastructure delivery and operate energy smart data scheme | → Create new water system operator focused on long-term national resource plan & infrastructure delivery |

Establish an Accelerated Innovation Agency on a statutory footing as a new, 'n+1' innovation regulator

Innovation often cuts across traditional sector boundaries, but sector-specific regulators focus narrowly on their industries and are structurally risk-averse. Instead, the government should establish a new, independent, Accelerated Innovation Agency (sometimes called an ‘n+1 innovation regulator’) to inject pace, urgency and competition into the regulatory ecosystem itself, with a clear mission to unlock innovation across the economy.

It should have a dual mandate: to accelerate enabling pathways in mature, regulated sectors like energy or financial services, and for novel, frontier, disruptive technologies without an existing regulatory pathway.

Initially, this should be set up as a new shadow unit in No. 10 — with authority and influence from the start — focused on moving onto a statutory footing and scoping its necessary powers. This will include issuing temporary licenses to firms in both novel and mature markets, stepping in where sectoral safety regulators have failed. This matters because new innovations often have a different risk profile than mature technologies, so authorities struggle to prioritise the work required to authorise these new entrants.

A new body with an explicit focus on helping innovations to get to market would effectively pool subscale innovation appetite from sectoral regulators – akin to pension fund consolidation – into a singular, focused entity. If resourced to move quickly, the Accelerated Innovation Agency would fill a critical gap in Britain’s institutional architecture, ending the pattern of promising technologies being stranded by outdated regulatory models and supporting a more dynamic, innovative economy. It would support the continued success of the most capable, high-agency parts of the state: for example, some of ARIA’s work in geoengineering and neuroscience will require novel regulatory permissions, and failure to reform innovation regulation risks constraining a recent state capacity success.

Unfortunately, while this could and should have been the model for the Regulatory Innovation Office (RIO), early structural choices have hobbled its potential:

- Post-election, HMT/DBT’s apathy towards innovation and DSIT’s apathy towards wider regulated sectors meant the RIO was initially housed in DSIT and narrowly scoped on a handful of novel technologies, rather than having a dual mandate.

- Instead of getting funding and authority upfront, it must ‘prove the model’ to the Treasury before the Spending Review, with limited power to achieve results.

- The RIO’s lack of upfront funding is compounded by having no financial influence over regulators, as it is housed in DSIT which doesn’t sponsor any.

- The RIO has started slowly, taking months to appoint a Chair and staff a team. The new team also decided to start from scratch by contracting generalist consultants to re-interview experts about the RIO’s focuses, despite detail having already been drawn up pre-election.

This is a recipe for institutional inertia. While in pre-statutory phase, the RIO should always have been a joint unit between DSIT and the centre (No10 or Treasury). Without a major change in pace and strategy, it will fall short of its potential and the country’s needs. The government should likely cut its losses and start again.

Focus sectoral attention on ‘System Operators’ built for accelerating infrastructure delivery, not central planning

After the merger, the remaining sectoral functions could be split between specialist, technical, product safety agencies (e.g. the Drinking Water Inspectorate), and an existing or new public body focused on infrastructure investment, planning, and construction. In energy, this exists as the National Energy System Operator (NESO). In water, while the NAO highlighted that no regulator has a coherent national plan, they might reasonably argue that this isn’t their main role. Therefore, a national water system operator should be established for integrated planning capability.

However, early signs from NESO suggest the model still needs refinement. To succeed, system operators must:

- Focus on enabling rapid network build-out by encouraging contestability, not acting as central planners – this means behaving mostly as an orchestrator, not necessarily always an operator

- Build and organise around strong data capabilities to deliver consumer-facing smart data schemes and whole-system network modelling

Contestability is critical to accelerating infrastructure abundance. It means allowing qualified third parties to design, finance, and build new assets and provide competitive incentives in the system. This approach is emerging in electricity distribution, where Independent Distribution Network Operators (IDNOs) are handling much of the last mile network build. However, monopoly DNOs are still responsible for reinforcing upstream infrastructure and can be reluctant to do this in advance of downstream need. But the contestability principle should also underpin transmission, as Adam Bell explains:

“IDNOs cannot solve the connections problem for us, because they build networks that essentially plug into existing networks and do not increase the capacity of those networks for those within them. What they do represent, however, is an important break with the idea of networks as a monopoly: they are a rejection of the idea of a monopoly of origination of new network projects…

New transmission projects can essentially only be proposed by the National Energy System Operator (NESO) or by the operators of the old nationalised network, the Transmission Operators (TOs)…They will build out infrastructure in response to demand at their own pace…Companies that want a transmission connection have to apply to one of these TOs for one, and again, there is a queue.

If we want to unlock growth in the UK, at the heart of it has to be the idea that anyone who wants a network connection can have one in a timely fashion. We cannot achieve this with the current total monopoly at the transmission level and the partial monopoly at the distribution level.”

An alternative to NESO’s ‘build the grid first’ default, suggested by Alex Chalmers, is to permit faster connections for new generation projects, with the condition that they shut off when the grid is at maximum capacity. This 'connect and manage' model exists in Texas, which has delivered a phenomenal renewables buildout. This is partly because faster grid connections mean the demand signals for upstream network expansion arrive earlier, accelerating transmission and distribution upgrades.

Large electricity users like data-centre developers, who are often more sensitive to speed than cost, should be allowed to finance and operate their own private networks with on-site generation. These systems require 99.999% power reliability, so they will still need a grid connection to sync to a stable external current frequency, but the energy is generated on-site. The result is new capacity where the costs are internalised by energy-intensive business users, not passed onto consumers.

The government has a huge opportunity to build effective sectoral state capacity via system operators. Alongside contestability, system operators should also integrate and be organised around deep data capabilities to fulfil their role effectively.

This is critical for accelerating physical infrastructure build-out and the software and data infrastructure required for orchestrating the network and enabling differentiated consumer experiences. In energy, the market is shifting from commodity retail to disaggregated services — like EV charging and heating — while smart data infrastructure could support a new, virtual ‘social tariff’ based on auto-switching rather than direct political price-setting. Retail price caps are not going away overnight – and they have encouraged energy companies to compete on customer outcomes and by driving down costs – but we must start dissolving their role to allow for greater investment while keeping consumer bills competitive.

This relies on better data. While the government is legislating to expand smart data schemes beyond Open Banking, there’s an underhang due to the lack of institutional capability. In energy, NESO is the obvious candidate, but despite only being established in 2024, it lacks deep data capabilities. This is a basic requirement for a modern, AI-era network coordination body and is critical to operate the smart data scheme and wider network orchestration. One solution is to integrate some or all energy data bodies like Elexon, the Data Communications Company, or Electralink into NESO.

Similar lessons apply elsewhere, with the Corry Review finding that water regulators equally lack critical digital capabilities. New bodies like GB Railways and the ‘future entity’ for Open Banking – perhaps combined with the FCA’s delivery functions after restructuring its policy and regulatory divisions – should also play this role in their sectors.

Finally, sectoral system operators should also work closely with the government’s new National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority (NISTA). NISTA should similarly embed a different way of working from day one, building – and being built on – core data infrastructure to speed up project delivery. This should include tracking project consents across bodies and speeding up handover processes, to tighten the sequence between design, procurement, planning, and construction. Government could also leverage this data capability to tackle its challenge of having no real-time insight into materials, supplier, or labour availability. This lack of insight limits its ability to deliver major projects on time and budget across transport, water, energy, housing, and other sectors, as Raoul Ruparel and BCG show.

Reset regulatory pay, incentives, and accountability structures

Rationalising economic regulators would also pave the way for many wider improvements in regulatory quality, pay, incentives, and governance, as Stuart Hudson, former Senior Director of Strategy at the CMA, recently argued.

Consolidation would free up resources, allowing fewer staff to be paid higher salaries. For example, instead of Ofgem and Ofwat independently assessing the cost of capital for their sectors, it would be more efficient to consolidate this activity into a single body rather than having multiple regulators compete – while constrained by civil service salary schemes – for scarce expertise. This step would make regulatory posts more attractive to the private sector talent that is often missing particularly at senior levels.

A single cross-economy competition and consumer body would also be less vulnerable to rent-seeking behaviour and regulatory capture from incumbents. It would provide less of a vehicle for politicians to demand ‘doing something’, limiting the flow of new regulations. We cannot halt demands to ‘do something’ – the constant ratchet and scope creep of regulation is a fact of democracy – but we can design institutions and mechanisms that channel this feeling constructively rather than adding to unproductive regulatory bloat.

As such, the government should also simplify and reset the relationship between Ministers and regulators. This should entail returning policymaking to sovereign departments, not only from Ofwat and Ofgem but also other sectoral regulators like the FCA. In exchange, Ministers must resist both outsourcing and meddling. For example, ad hoc requests outside pricing reviews could be channeled into more frequent, constructive correction mechanisms (such as 6-monthly performance reviews) to deliver structured feedback instead of relying on media-driven interventions.

Institutional rationalisation also presents the opportunity to simplify departmental sponsorship: a unified economic regulator should be overseen by a single department such as HMT. The same principle could apply to regulators who are highly strategic, yet would not be part of this merger and are currently sponsored by departments with very different priorities. For example, in the UK, the Office for Nuclear Regulation is sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions. In South Korea, which has approved 19 reactors since 1990, the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission is "established directly under the Prime Minister".

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Adam Bell, Matt Bevington, Robert Boswall, Arthur Downing, Mark Holmes, Ben James, Tom Loosemore, Eleanor Mack, John Myers, Guy Newey, Dan Nicholls, Tom Parker McClean, Freddie Poser, Pedro Serôdio, Marissa Sterling, Jack Wiseman, Julia Willemyns and Suhayl Zulfiquar for their input and insight. All views, errors, and omissions are the sole responsibility of the author.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]