Table of Contents

- 1. Replace stamp duty with an annual property tax

- 2. Reformulate the triple lock on state pensions

- 3. Fix incentives to support founders & scale-ups

- 4. Remove Carbon Price Support to reduce energy bills

- 5. Ten small but easy fixes

- 6. Authors

The Chancellor finds herself in an unenviable position. Weak growth and high borrowing costs mean that, to meet her fiscal rules, she must find at least £20 billion of savings, either through cutting spending or raising taxes.

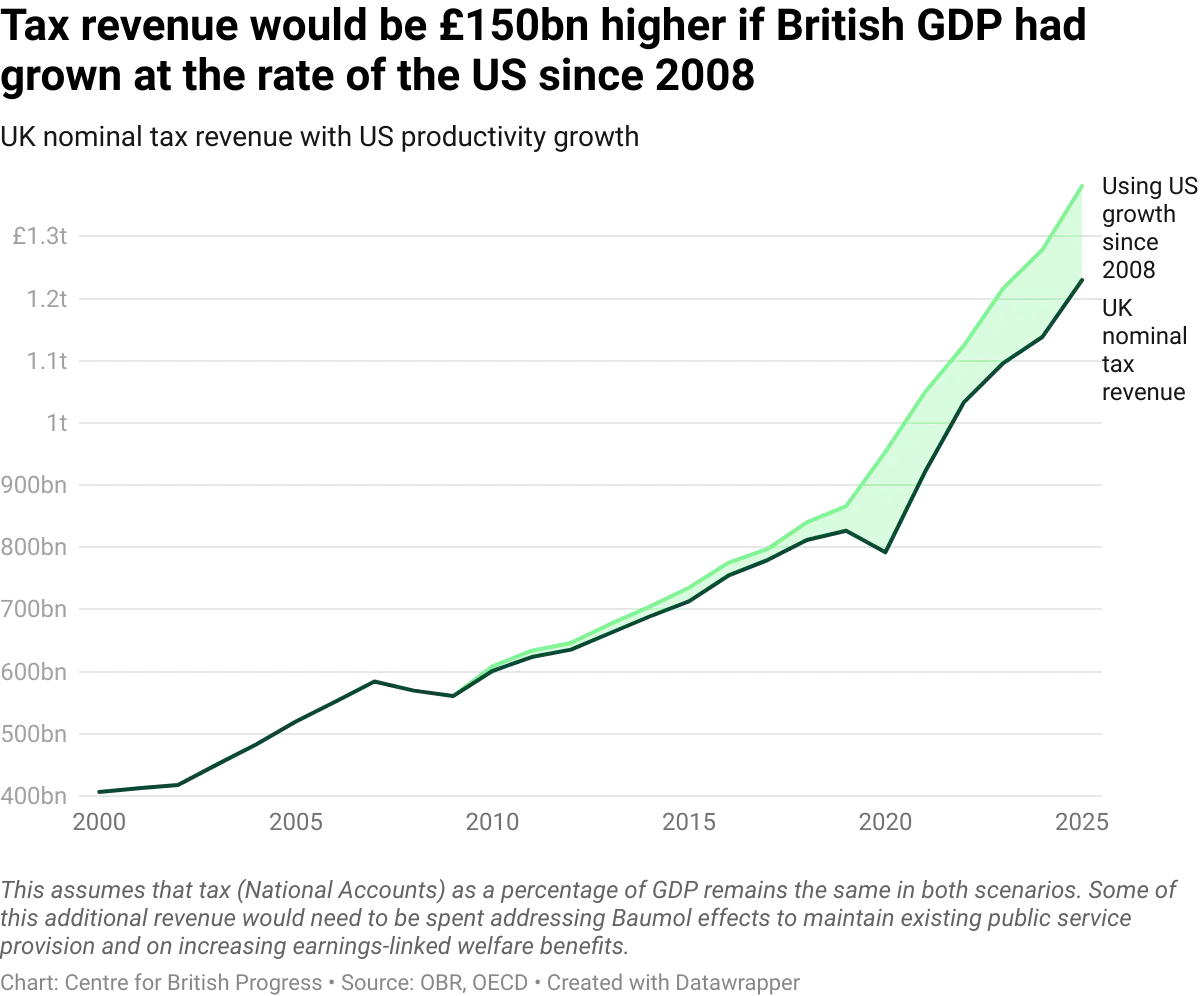

The good news is that there is one clear route out of this predicament: growth. If we had grown at the same rate as the US since 2008, the Chancellor would have an extra £150 billion to fund government spending with. That’s enough to fill the fiscal hole five times, or indeed to reverse cuts on winter fuel, foreign aid and welfare spending, and have enough left over to upgrade our schools and hospitals, pay for families to replace boilers with heat pumps, build thousands of new council homes per year, and make sure no child goes hungry. Government spending would have undoubtedly increased if our productivity had increased as much as in the US, but that would have meant much better public services.

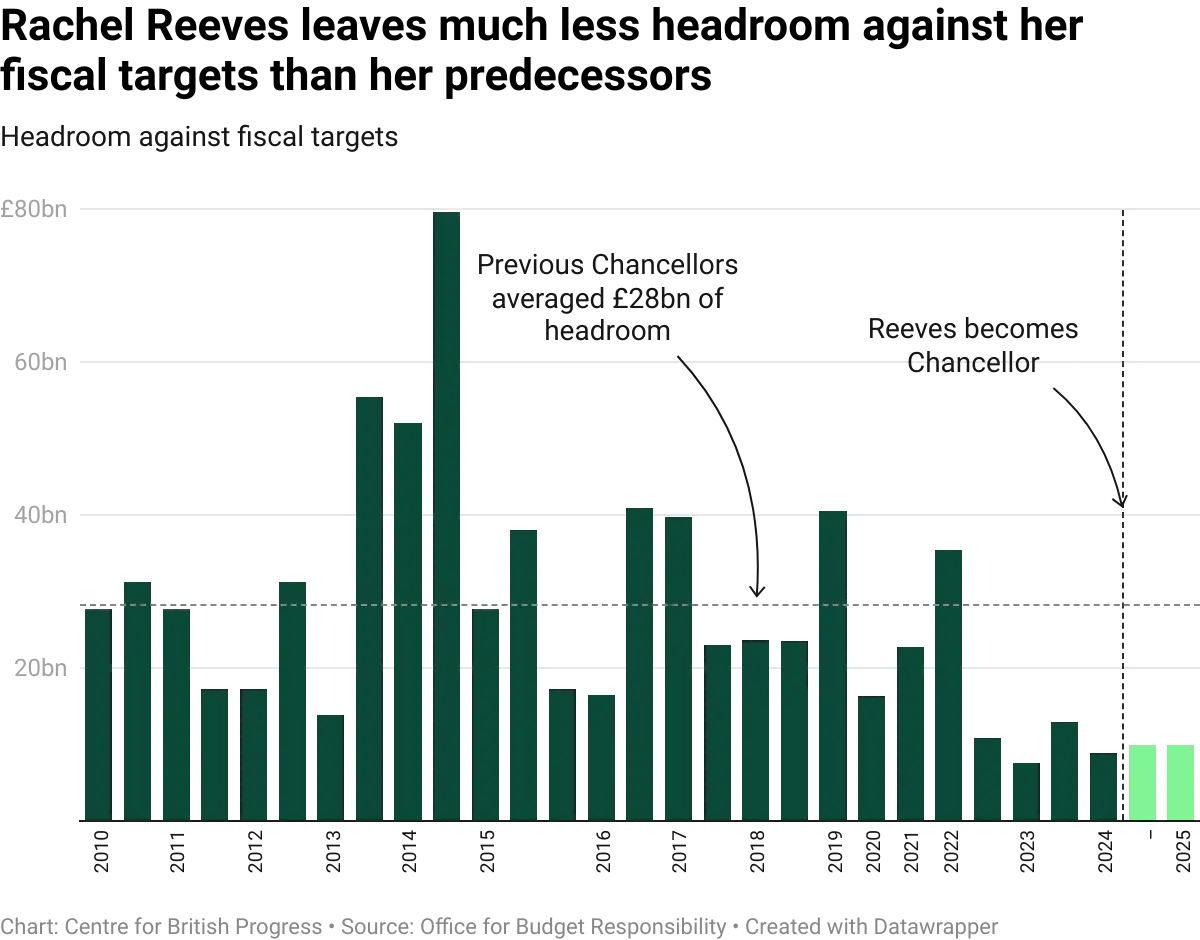

Growth is the answer to a politics defined by zero sum battles and unpopular austerity. Policies for growth pay twice: not only do they generate taxation income, they also allow the Chancellor to borrow more, as per our fiscal rules, reducing the need for tax rises or spending cuts. On her own fiscal rules, the Chancellor has far less headroom than that of other chancellors since 2010.

This situation has deteriorated since the Spring Statement. We have combined data from the IFS with recent downgrades in productivity growth, as well as changes in policies, gilt yields and wider economic factors, to estimate that the Chancellor has lost almost £30 billion in fiscal headroom since March.

UK Government bonds now have a higher yield than those of Italy and France. This reflects differences in inflation and risk premiums between the countries.

And, to make things even harder, the Government is constrained by its promises not to increase the taxes that make up the majority of its revenue.

Growth offers a positive flywheel: growing economic activity boosts revenues, which can then be used for investment and tax cuts, further fueling growth. Without growth we risk a negative spiral of stagnation, requiring more tax rises and spending cuts, which in turn fuel further stagnation.

The Government is therefore right to prioritise growth as its “number one mission”, but our harsh fiscal constraints mean that Budget will be a test of resolve: there are better and worse ways to raise money, and indeed to spend it, if we are to get onto that positive flywheel of growth.

In this article, we bring together 14 Centre for British Progress proposals on fiscal policy for this Budget. Together, these proposals would increase fiscal headroom by over £10 billion, significantly reducing the fiscal black hole.

Replace stamp duty with an annual property tax

... but let people choose it when they next buy a house

Treasury revenue (per year) | Growth impact | |

|---|---|---|

Short run (by 2030) | c.£1-2 billion | Substantial: increased volume of transactions due to removal of tax wedge |

Long run (by 2050) | c.£8 billion | Substantial: dynamic productivity benefits from workers being able to move closer to higher paid jobs. |

Everyone hates stamp duty. Everyone, especially economists, knows an annual property tax would be better. The experts in our growth survey backed replacing the tax as one of the best things the Chancellor could do for growth because stamp duty gums up the property market and makes it costly to move house. As a result, people stay in the wrong place for longer: workers pay a penalty for moving to new job opportunities, empty-nesters are effectively fined for downsizing, and new parents can’t afford homes large enough for their families.

The challenge, however, is in designing a tax system that simultaneously:

- Fully removes stamp duty

- Leaves no one worse off than on the current system

- Raises money for the Treasury from day one

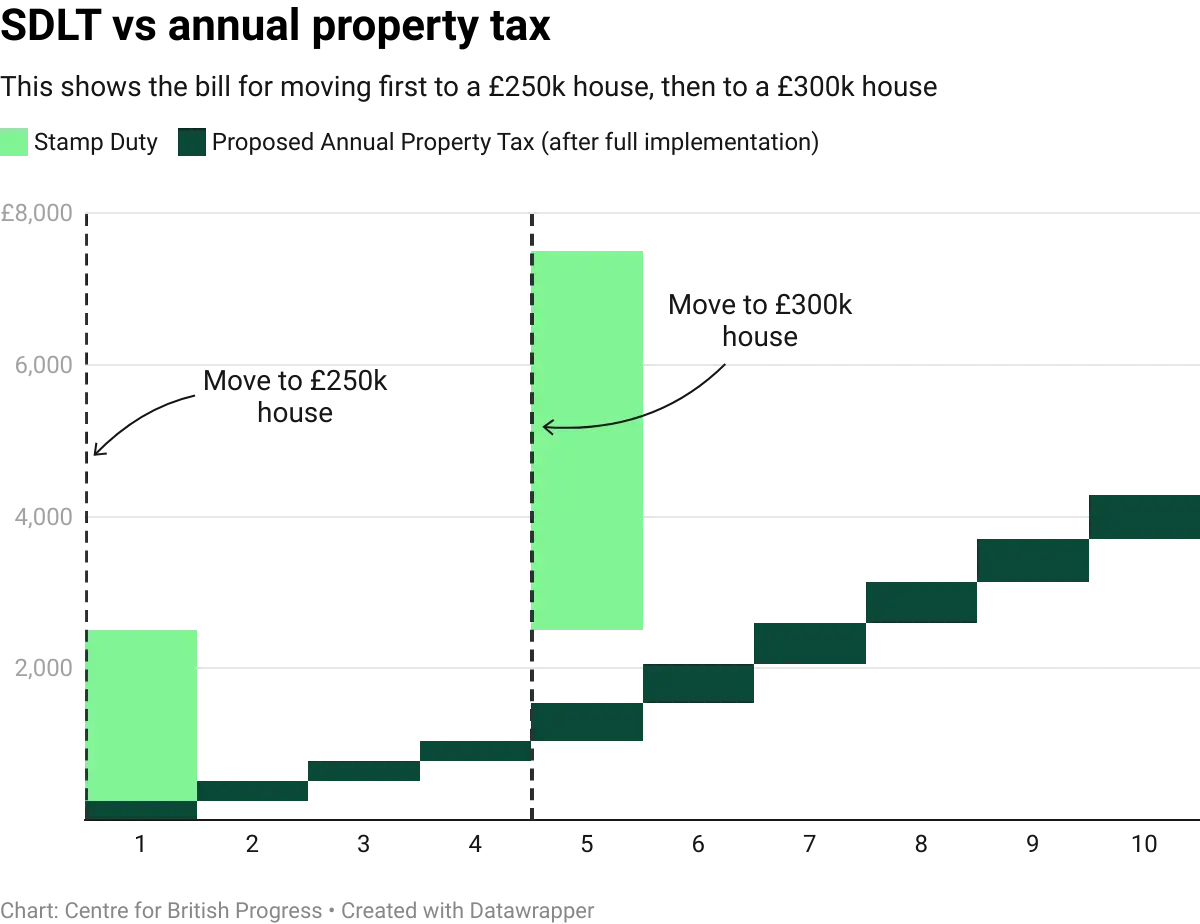

We believe we have a solution. We propose a scheme to give buyers a choice, so that when you next buy a house, you can either pay stamp duty on the current system, or you commit to paying an annual property tax - 0.16% for an average property worth £300,000 (which works out at £480 a year). For someone who moves house twice in 10 years, this will be a huge saving on the current system, as shown in the graph.

Our proposal would be revenue positive from day one. The ten-year phase in and additional revenue-raising measures (including an additional 0.5% on properties over £2m) mean that, unlike alternative proposals, our reform both helps the Chancellor meet the fiscal rules and leaves the vast majority of homeowners no worse off.

Together, our proposals would:

- Raise around £1.7 billion above the current SDLT baseline in year one of implementation, rising to around £8bn annually above baseline by 2050.

- Reduce long-term borrowing costs due to forecast future revenue.

- Create more stable and predictable revenue for HMT.

- Increase productivity, GDP and tax revenue resulting from new economic activity. This includes new property transactions (which otherwise would have been made impossible due to the SDLT wedge), and dynamic effects resulting from workers moving to higher-paying jobs.

- Have no effect on the vast majority of homeowners – there are between 140k and 170k properties worth more than £2 million in England and Wales, representing between 0.55% and 0.65% of the housing stock.

- Create substantial savings for buyers, who no longer have to pay SDLT (or a reduced proportion, during the transition) on their purchases.

Reformulate the triple lock on state pensions

Treasury savings (per year) | Growth impact | |

|---|---|---|

Short run (by 2030) | c.£6 billion | Medium: savings can be spent on infrastructure or cutting taxes |

Long run (by 2050) | c.£45 billion | Medium: even more savings can be spent on infrastructure or cutting taxes |

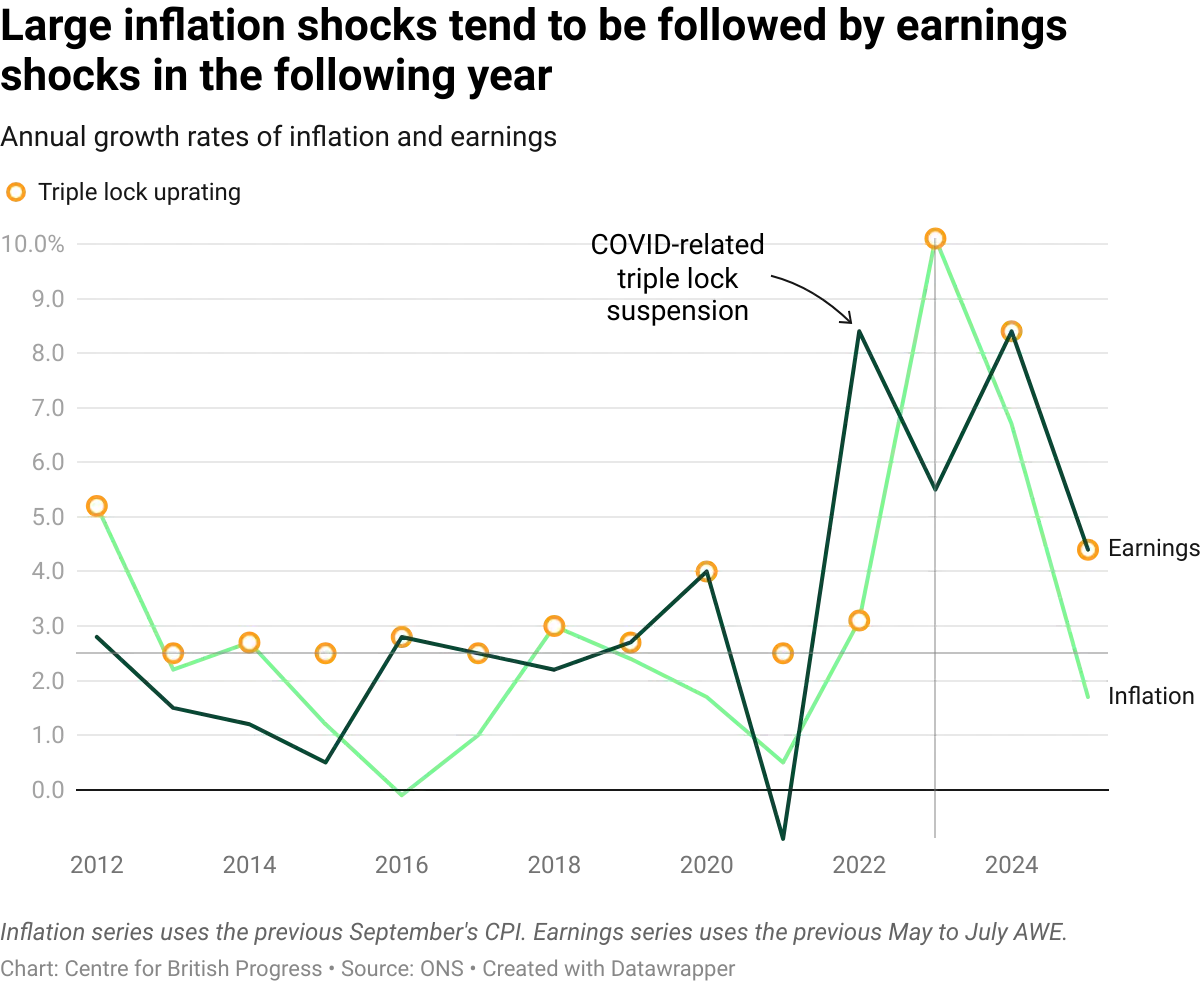

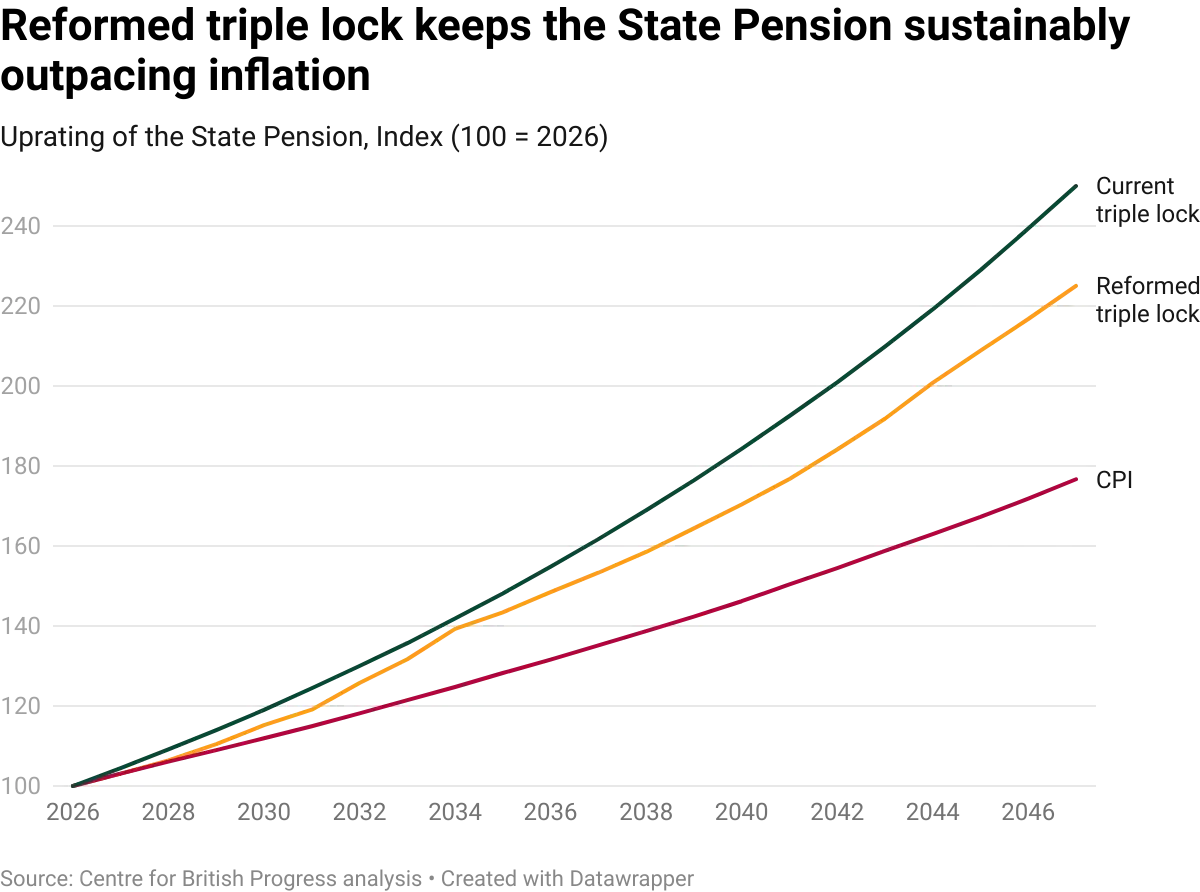

The ‘triple lock’ on state pension growth has become an important way of ensuring that pensioners, many of whom are in the lowest income brackets, continue to receive a fair income. However, the formula in its current form is unsustainable. In particular, the triple lock ‘double counts’ the same rise in earnings, because of the one year lag between earnings and inflation (as shown by the graph below).

We propose a tweak which would protect the core of the triple lock while addressing this anomaly. Namely, the Government should change the calculation so that two of the “locks” reflect changes over a ten year period, rather than just the last 12 months. The changes are summarised in the table below:

Current calculation | Our proposed calculation | |

|---|---|---|

1. Earnings lock | Earnings growth over last 12 months | Amount required to match earnings growth over last 10 years |

2. Inflation lock | Inflation over the last 12 months | Inflation over the last 12 months |

3. 2.5% lock | 2.5% | Amount required to match annual 2.5% growth over last 10 years |

We forecast that this could raise £6 billion annually by 2030, and over £45 billion by 2050, while retaining the core of the triple lock. As the graph below shows, this still allows the state pension to sustainably outpace inflation, and ensures the Government’s commitment to the triple lock.

Fix incentives to support founders & scale-ups

Treasury revenue (per year) | Growth impact | |

|---|---|---|

Removal of EIS & VCT | c.£1 billion | Probably neutral – we do not think these incentives make much difference to growth |

Expand EMI | -c.£1 billion | Huge potential in the medium term: more firms choose to build and scale in the UK. |

Founders are the engines of growth. The UK should aspire to be the best place in the world to invest and scale in ambitious companies, and our fiscal incentives should reflect that. The Government is right to rule out an exit tax, which would make the UK a less attractive place to build, but there is more that can be done to attract investment in Britain – including some measures that can save the Treasury money.

Some of our investment incentives, especially the Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) and the Venture Capital Trust (VCT), have outlived their purpose and are now poor value for the taxpayer. EIS and VCTs were introduced in the 1990s to stimulate a fledgling venture ecosystem. But today, Britain is Europe’s leading startup ecosystem by far, and these schemes have nonetheless been extended and expanded multiple times since their inception, costing approximately £1 billion every year.

The Government should consider scrapping EIS and VCT, and instead expand Enterprise Management Incentives (EMI). Under EMI, companies can award employees up to £250k in share options. In most cases, employees only pay capital gains tax, while gains are de facto exempt from income tax and national insurance. In principle this is a highly attractive scheme which helps early-stage, cash-poor companies to compete for exceptional talent and increase their odds of success.

EMI is a much better incentive to support growth and domestic value capture, but its cliff-edges need updating. The limits of £30 million in assets and 250 FTE employees, unchanged since 2002 – now penalise success, excluding both new companies that launch with major funding rounds and established firms as they begin to scale.

Crucially, EMI is remarkably fiscally-efficient: the government can encourage far more employers and employees to locate, hire, and scale in Britain than it ever ‘pays out’ to, because most technology companies do not reach a liquidity event and therefore don’t trigger EMI relief.

Redirecting up to £1 billion spent on EIS/VCTs towards expanding EMI (and resourcing British Sovereign Capital) would ensure the benefits of companies’ success are more widely felt by the full labour force and also incentivise companies to deepen their economic commitment to the UK by building and scaling their operations here, at a key inflection point for the business.

Remove Carbon Price Support to reduce energy bills

Treasury revenue (per year) | Growth impact | |

|---|---|---|

Removal of CPS | -£440m | £1.3 billion reduction in bills; downstream benefits from attracting investment, especially in AI. |

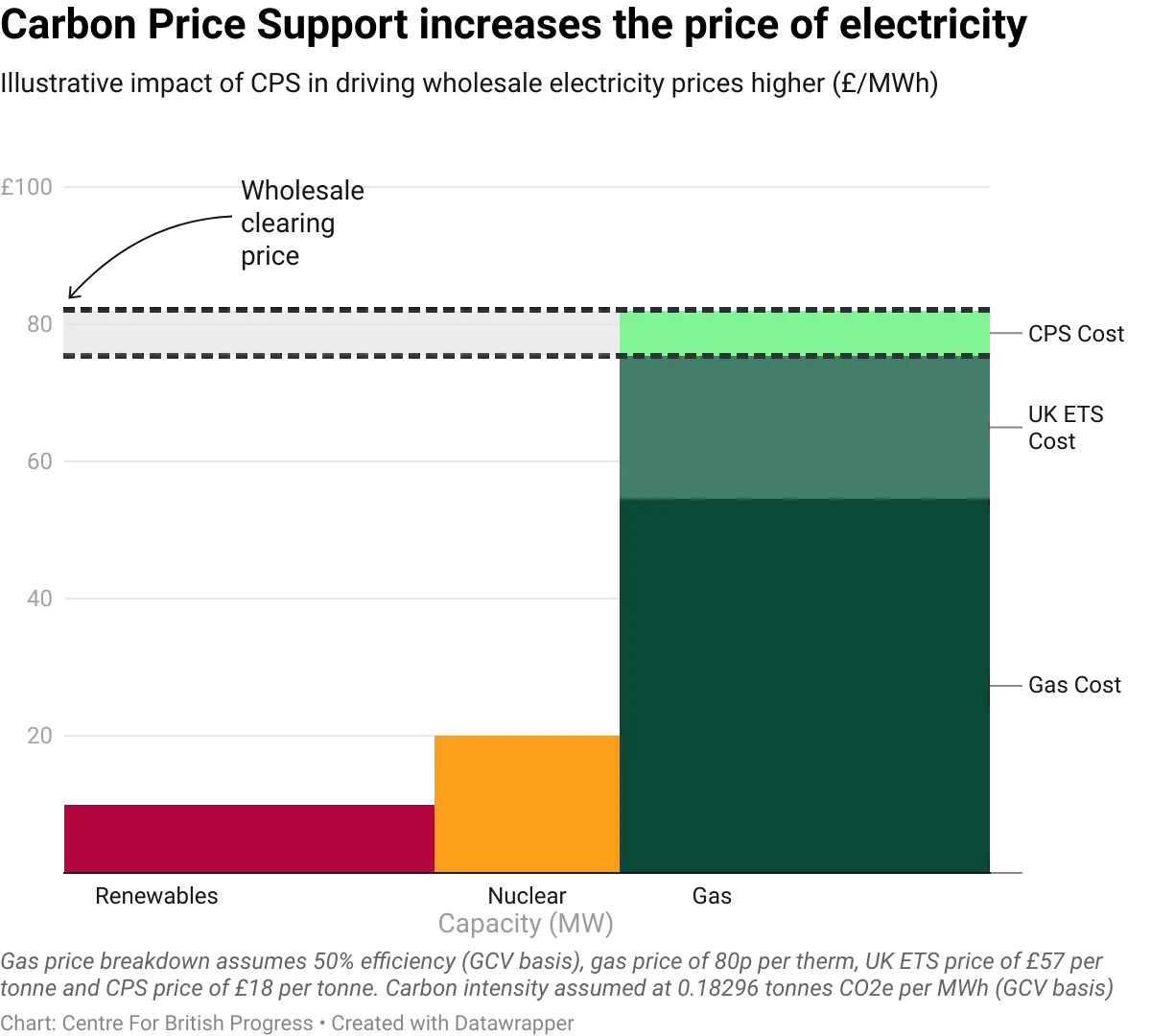

Energy costs are a major drag on UK growth. Not only do they comprise a large proportion of ordinary households' budgets, but they also hamper British industry, which faces some of the world’s highest electricity costs. Getting energy costs down is particularly important for attracting AI investment, which could be the backbone of the next industrial revolution.

There are few levers the Government can pull to reduce energy costs in the short run, besides direct subsidy or the removal of levies. Most subsidies or levy suspensions are zero-sum. That is, they benefit energy consumers only as much as they cost the taxpayer.

One exception to this is the carbon price support (CPS), which disproportionately hits energy consumers compared to how much it raises for the Treasury. In 2024, CPS increased electricity costs by more than £3.50 for every £1 it generated for the Exchequer in 2024. Since CPS is levied on gas used to produce electricity, when gas sets the price, this price gets inflated by CPS. Nuclear and renewables providers (excluding those on contracts-for-difference) then charge the same price, but without accruing any further revenue to the Treasury.

CPS also probably does more harm than good for the climate. It was designed to help the grid transition away from coal, which has now happened. The big challenge now is electrifying wider parts of the economy, for which CPS is actively unhelpful, as it pushes up the cost of electricity. Abolishing or zero-rating CPS would reduce bills by £1.3 billion for households, businesses and the NHS, while supporting the switch towards greener, electrified heating and transport.

Ten small but easy fixes

We have found ten niche, but politically low-cost, ways for the Treasury to raise £4.75 billion per year by 2030. We have been careful to ensure that they have limited, if any, negative impact on growth – some would indeed be positive. In the context of a broad consensus that the UK’s tax system is overly complicated, these proposals also represent a realistic first step towards simplifying the system in ways that are acceptable to backbenchers and bond markets alike.

The proposals are summarised in the table below, and you can read the full paper here.

Policy Type | Policy | Treasury revenue (annual, 2030) |

|---|---|---|

Removal of tax reliefs | 1. Remove the Vehicle Excise Duty exemption for vehicles manufactured at least 40 years ago | £230m |

2. Abolish the empty rates exemption for listed buildings | £510m | |

3. Eliminate the starting rate for savings | £440m | |

4. Remove the tax free lump sum entitlement from new pension contributions and accumulation | £70m (significantly more in future years) | |

5. Abolish the Patent Box | £1.6bn | |

Reducing the generosity of reliefs | 6. Reduce the effective tax relief rate for audio-visual expenditure credits | £420m |

7. Place sensible limits on employee share schemes | £440m | |

8. Reduce the Capital Gains Tax allowance | £140m | |

Anti-corruption and tax evasion | 9. Ban large cash transactions | £850m |

10. Enforce foreign companies’ disclosure of beneficial ownership | £50m | |

Total £4.75 bn |

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]