Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Recommendations

- 3. Split up the BBB and establish British Sovereign Capital

- 4. Replace EIS and VCTs with expansions to EMI

- 5. Acknowledgements

- 6. Authors

Summary

Britain’s capital allocation institutions and incentives are designed for a bygone era. Infrastructure once built to stimulate a nascent ecosystem must now be re-engineered for a world of geopolitical and economic upheaval.

We face three inflection points:

- British founders and companies are increasingly considering relocating or growing overseas, so we are set to miss out on compounding gains of scale while growth stagnates.

- Other countries increasingly treat firms in key industries as key strategic assets. We must scale capabilities and companies that give us equivalent leverage.

- Britain’s services-based economy may be highly exposed to advances in AI, which may put current sources of fiscal revenues under pressure.

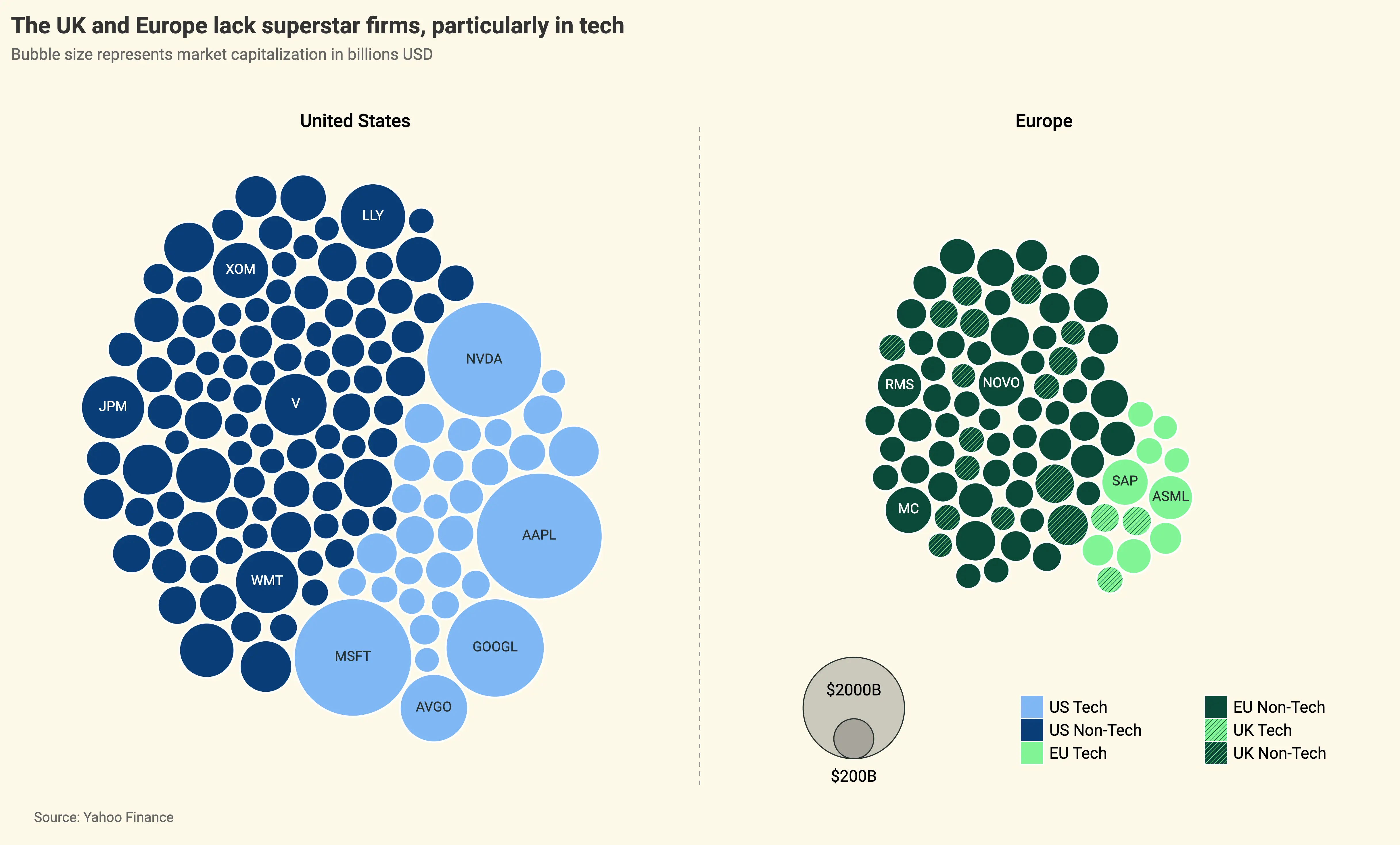

These trends coalesce into a problematic lack of superstar technology firms. As set out in our founding essay, the US now boasts eight companies valued at above $1 trillion, of which seven were founded in the last half-century and most in technology. Europe’s largest, Novo Nordisk, is worth less than half of that, while Britain’s largest, AztraZeneca, is worth about half again.

While equity value is not a direct measure of economic benefit to the country, it is a reasonable proxy to target because these companies have enormous spillover effects as major employers, R&D investors, tax contributors and developers of critical national capabilities that provide outsized geopolitical leverage.

In 2024, the US was nearly three times more VC-intensive per capita than the UK, with $215.4bn invested in the US compared with $16.3bn in the UK. While this gap may partly be a function of supply-side issues limiting the pipeline of investable opportunities, there are clearly demand-side issues – institutional funds in the UK allocate less to private markets in general than international comparators – while today’s ecosystem is also a lagging indicator. Looking ahead, we may need to unlock much more capital so founders and funds can tackle more capital-intensive problems in low-productivity, critical industries.

Yet we are getting a poor return from our investment incentives and institutions, which are still geared towards stimulating the ecosystem rather than building enduring, global winners from Britain. What may once have been generative is now value-destructive. Early-stage incentives frequently turn companies into zombies, slowing the re-allocation of talent and capital towards more productive ends without meaningfully improving the pipeline of companies. Meanwhile the state’s investor, now the largest LP in UK venture, is actively avoided by the best founders, companies and funds due to both substantive and signalling issues.

To fix this, we must reorient our tax incentives and create a new sovereign capital institution. A new body would provide a clean break from the BBB’s current reputation, which not only limits its ability to unlock institutional capital but also to partner with the best venture funds allocating it. Its mission should be to be the world’s best LP, while direct investing should be reserved only for exceptional cases where the state must lead, such as national security or AI sovereignty, and only if exceptional investors can be hired and empowered to deliver.

Recommendations

We propose two complementary reforms: first, rebuild Britain’s sovereign capital allocator, and second, refocus fiscal incentives on domestic scale and value capture.

A: Split up the BBB and establish British Sovereign Capital

In Part A, we argue that the British Business Bank, now one of the most powerful allocators of public capital, is underpowered for what Britain needs today. The BBB is slow-moving and constrained by its mandate, pay structures, culture and incentives – making it an unattractive LP for the best funds, both for substantive and signalling reasons. While not established as a sovereign wealth fund, it is increasingly being asked to play a similar role as a systemic, strategic capital allocator as it manages a ~£10bn venture capital portfolio and takes on an expanded role in unlocking major institutional capital. Yet despite the expanding remit, little attention has been paid to how the BBB operates, including its capability to invest directly. SovAI is another critical organisation which is both reliant on the BBB and similarly constrained by civil service pay scales.

The lesson from ARIA and AISI is clear: exceptional state capacity for exponential technologies is possible, but requires new, autonomous entities with distinct missions and pioneering leaders, rather than slow, incremental reform of existing bureaucracies. We should apply this lesson to both the BBB and SovAI.

- Split up the BBB – separating its risk-seeking, strategic venture investing from other Investment and Banking programmes – to create British Sovereign Capital (BSC), a fully independent, risk-seeking institutional and strategic investor to fully separate this from non-commercial, linear, small-business-focused guarantee and lending programmes

- At minimum, bring the following BBB programmes into BSC: Venture/Growth programmes managed by the BBB’s British Patient Capital arm, Enterprise Capital Funds (ECF), Long-term Investment for Technology and Science (LIFTS), and the National Security Strategic Investment Fund (NSSIF)

- Spin out SovAI to ensure autonomy and velocity, rather than being constrained by the BBB and DSIT, or integrate into British Sovereign Capital

- Make the BSC a best-in-class Limited Partner, focusing on crowding in institutional capital and backing funds and fund-of-funds to fix the structural issue of large institutions being unable to allocate to small funds, of which there are many in the UK. Consider using ECF-style gearing or temporary fee support to crowd in private capital and to accelerate these institutions’ in-house capability to be a long-term allocator to venture. In turn, reserve direct investing only for exceptional strategic cases (e.g. SovAI, NSSIF), to prevent wider adverse selection and market distortion.

- Undo recent BBB restrictions on deal geographies and sizes, so that BSC and its partner funds can once again invest not only in UK-HQ’d companies but also UK-founded companies who create a US holding company

- Enable global value capture alongside domestic support by allowing BSC/BBB-backed VC funds to invest abroad, while requiring UK investment in line with the BBB’s LP share

- Appoint a new Chair to the BSC/BBB to deliver on a new mandate that would deliver both financial returns and strategic sovereignty, delivering a UK venture ecosystem that is as attractive, capable and deep as the US (on a per capita basis). This would require giving the Chair full autonomy to reform talent, pay, incentives and structures so that BSC is a globally credible partner.

- Leverage BBB/BSC portfolio data across government to match startups with procurement, regulatory and strategic opportunities, turning quarterly investment data into a real-time intelligence capability for industrial strategy

B: Replace EIS and VCTs with expansions to EMI, to focus on scale and domestic value capture

In Part B, we argue that the UK’s flagship tax incentives – the Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) and Venture Capital Trusts (VCTs) – now cost ~£1 billion a year but deliver poor value, not only rewarding tax-relief arbitrage but disincentivising genuine risk-seeking and talent re-allocation.

We propose replacing EIS funds and VCTs with expansions to Enterprise Management Incentives (EMI). This is a highly fiscally-efficient way to target domestic value capture – encouraging far more employers and employees to build, employ and scale in Britain than the Exchequer ever has to ‘pay out’ to – because most do not ultimately claim tax relief.

- Abolish EIS and VCT funds, saving up to £1 billion a year and ending the cottage industry of tax shelter funds optimised for reliefs rather than returns

- Retain the Seed Enterprise Scheme (SEIS), which remains useful and low-cost, and keep EIS for individual angels, who are more likely to provide genuine mentorship and be focused on investment upside

- Expand EMI’s current cliff-edges to capture the compounding gains of scale, by:

- Raising the outdated £30m and 250 employee limits to £120m and 500 respectively. We estimate that, for every £1 of foregone tax, the current scheme delivers £2.65 in economic benefit and this expansion would generate an additional £1.84.

- Consider creating an additional ‘EMI Plus’ tier for larger scale-ups with much higher thresholds (e.g. no asset limit, 2500 FTEs), offset by higher rate of CGT (32%, in line with carried interest). This expansion could still deliver a £1.46 return for every £1 of foregone tax, while keeping incentives aligned with scale.

- Alternatively, shift to a US-style Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) scheme, exempting the first £5-10 million of gains from CGT entirely.

Split up the BBB and establish British Sovereign Capital

Here is how three of the world’s leading sovereign investment funds describe themselves:

- Temasek (Singapore): “a global investment company headquartered in Singapore”

- Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund): “We work to safeguard and build financial wealth for future generations”

- Public Investment Fund (PIF, Saudi Arabia): “PIF continues to drive the economic transformation of Saudi Arabia while shaping global economies”

Now here is how the British Business Bank describes itself: “a government-owned economic bank specialised in helping businesses in the UK access financial support.”

In many ways this comparison is unfair – the BBB was not created to be a sovereign wealth fund – but that’s the point: Britain has a parochial economic development bank focused on job creation and fixing ‘access to finance’ market failures, rather than a capital allocator with the capability, culture and velocity to build wealth, double down on winners and advance our strategic interests.

This matters because, whether or not you think the UK should have such an institution, the BBB is increasingly being tasked with allocating capital as if it were such an institution. Since 2014, the BBB’s remit has ballooned from an initial £1bn commitment to more than £25bn in investments, loans and guarantees, yet there has been almost no attention on reforming the institution itself and making sure it is equipped to allocate this level of capital well.

Additionally, as AI shifts value from labour to capital, governments may need to diversify their fiscal base. Consumption, corporation and capital gains taxes will become more important, though intense jurisdictional competition for investors’ and AI companies’ tax residency may keep effective rates low. Building equity stakes might introduce challenges, but may ultimately be part of the necessary toolkit. For Britain, this means moving on from the BBB’s current mandate (domestic market failures) to focusing on capturing value globally via domestic funds.

Yet Britain’s major capital allocation institution is underpowered to meet the moment. While this is partly due to the mandate it has been set, if NBIM is focused on returns, Temasek secures strategic stakes in key value chains, and PIF does both, then the BBB does neither.

The BBB now plays an enormous role in UK science and technology policy

More than ten years since its founding, the British Business Bank is now an enormous organisation, managing everything from small business loans and regional development funds alongside major, high-growth venture funds. Under one roof, the BBB provides lending facilities for small businesses across the country, makes investments into national security tech via NSSIF, and operates the largest LP fund in UK venture.

Table 1: The government now manages £25.5bn of funds and commitments via the BBB (source: Spending Review 2025)

BBB Financial Capacity | Pre Spending Review 2025 | Post Spending Review 2025 |

|---|---|---|

Loans & Equity | £10.4bn | £17.5bn |

Guarantees | £4.8bn | £8.0bn |

Total | £15.2bn | £25.5bn |

While a full breakdown of the BBB’s £17.5bn loans and equity programme is not currently available, at least ~£10 billion of public money is now allocated to risk-seeking investments in high-growth technology businesses and strategic industries, with a number of these programmes expected to growth further:

Table 2: The BBB now manages at least £10bn in ‘sovereign capital’ (sources: BBB, SovAI)

Programme name | Description | BBB funding (£ billion) |

|---|---|---|

Industrial Strategy Growth Capital | New investment to back companies across the IS8 sectors. | £4 billion |

BPC Venture / Venture Growth | Invests in venture and growth-stage funds to scale UK high-growth firms. | £2.5 billion |

NSSIF – National Security Strategic Investment Fund | Government fund and fund-of-funds for dual-use and defence-adjacent technologies, managed by BBB for DBT. | £0.33 billion |

LIFTS – Long-Term Investment for Technology and Science | Aims to catalyse pension and institutional investment into UK science & technology by co-investing in VC funds. | £0.25 billion |

UKIIF – UK Innovation Investment Fund | Fund-of-funds established in 2009 to invest in technology businesses with high growth potential. | £0.15 billion |

Future Fund: Breakthrough | Co-investment vehicle to crowd private investors into growth stage technology companies. | £0.425 billion |

LSIP – Life Sciences Investment Programme | LP vehicle for late stage VC funds focused on life sciences. | £0.2 billion |

ECF – Enterprise Capital Funds | LP vehicle for early-stage VC funds, with geared return mechanism for private investors. | £1 billion |

SovAI – Sovereign AI Unit | Blended vehicle to invest in companies, create UK AI assets and partner with frontier AI companies, managed by BBB for DSIT. | £0.5 billion |

£9.4 billion |

In effect, the BBB is operating what amounts to a ~£10bn investment portfolio that is sub-optimally fragmented and restricted to a series of overlapping, government-directed programmes, rather than being constructed and managed like a comparable, well-designed investment portfolio. This undermines strategic aims too: when funds are ringfenced to particular programmes, there is no thought given to the overall mix – such as the allocation to ECFs versus BPC, or the overall weighting of funds to industrial strategy priorities.

The BBB is not built for scale or speed. A new entity is needed to create best LP in UK venture

Interviews with leading UK fund managers, angel investors, founders and former BBB staff suggest it is unable to become a best-in-class partner to the best funds and companies:

- The BBB’s slow, risk-averse processes and non-commercial terms deter the best funds and talent, and prevent it from seizing windows of strategic opportunity: Both fund and direct investments are notoriously slow, creating adverse selection for both investments and staff. Most funds avoid raising from the BBB by default while many others choose not to return, citing administrative overheads, restrictive investing criteria and the signalling risk that accepting ‘money with strings attached’ sends to other founders and investors.

- Restrictive investing criteria create a self-defeating cycle: Funds backed by the BBB’s Enterprise Capital Funds programme must invest only in rounds capped at £5 million, even though the BBB’s own research shows AI rounds now routinely exceed that. Companies must also now be headquartered in the UK, with two-thirds of executives tax resident here (see Form Ventures’ breakdown). These rules prevent funds from backing even UK-founded firms that set up US holding companies to raise global capital, including most companies now founded at Entrepreneurs First, a leading UK accelerator. Similarly the only UK fund to back Eleven Labs at pre-seed was an ECF, well before it was worth $6.6bn, but they would no longer be able to do that deal because of its Delaware topco. A similarly perverse case is the Future Fund: Breakthrough scheme, whereby the BBB can force the sale of its stake if an investee ceases to meet certain ‘UK-located’ criteria, a provision that not only discourages global expansion but creates reputational and operational distractions.

- GP eligibility is also constrained: Solo GPs are de facto excluded from ECFs, despite former founders or operators often being among the most capable emerging managers. The BBB’s larger, later stage venture LP programme is less restrictive, but still tends to prefer funds investing in the UK rather than Europe – with the inverse also being true of the EU’s European Investment Fund – despite the best funds wanting to be free to invest across the continent. The result is a doom loop: by narrowing eligibility, the BBB excludes top-performing funds and startups and reinforces its own reputation as slow, parochial and risk-averse.

- Civil service pay structures prevent the BBB from hiring the investing talent required for it to make direct investments: Junior roles at the BBB start from £30k, at least half the salary for a junior investor at even a small fund (often £60-90k) let alone at large, leading firms (easily £100k+ plus bonus). Nor does the BBB offer any carry or performance-linked compensation. However capable its staff, these pay constraints make it implausible that the BBB can attract or retain the calibre of investors needed especially for direct investing, but also for LP investing.

- The BBB’s strategic position as the largest LP in UK VC is under-leveraged: The BBB receives unparalleled, quarterly data on a large swathe of British startups’ progress via funds’ reports. Yet this is only used for internal compliance instead of industrial strategy intelligence. This data should be leveraged to connect startups to procurement, regulation and export opportunities – where officials also often struggle to find startups – much like the role In-Q-Tel (a US government fund founded by the CIA) plays in US national security by screening technologies and connecting firms to the right end users and buyers. The OneWeb case illustrates the missed opportunity in the UK: while the state investing may have been defensible to keep a UK company in play in a strategic market, without the demand-side pull of an anchor product to drive product development it amounted to a capital injection to keep the company alive rather than a strategy to make it competitive.

Ultimately, these constraints are the result of a public institution historically focused more on downside protection and slow, deliberative, custody of taxpayer funds, rather than investment upside. But true stewardship of public money would be to build a reputable institution that can drive both returns and strategic outcomes. The BBB should be on the front foot, developing a compelling offer to compete for access in the very best UK funds, rather than simply reacting to the applications it receives.

To its credit, HMT and the BBB have recognised some of these shortcomings and have taken several steps towards reform. The BBB has been restructured into two distinct divisions – Banking (guarantees, funding, small business lending) and Investment (fund of funds, funds, direct- and co-investment, portfolio management) – in effect separating its linear, non-commercial high-street lending from its risk-seeking LP, venture and startup investing.

HMT has also issued a new financial transactions framework – which now accounts for government assets as well as liabilities – allowing it to establish a £16bn permanent capital base at the BBB. This step means that the BBB no longer has to return annual gains back to HMT, and allows it to shift away from ringfenced, government-directed ‘programmes’ into a more flexible, long-term, portfolio-based investment fund – as any large, serious, global investor focused on building wealth over time should operate.

Ultimately, these are necessary yet insufficient steps to turn the BBB into an effective capital allocator. Its mandate, pay structures and, most importantly, reputation all remain the same. Even DBT’s recent statement of strategic priorities, which does seek to evolve the BBB’s structures and focus, does not tackle these issues. It makes no diagnosis of the different capabilities, talent or cultures required for multiple programmes with different risk profiles to thrive, while still encouraging the BBB to invest directly.

Only a clean break and a new entity can overcome these challenges. We need British Sovereign Capital (BSC), a new institution focused on being the best possible LP to the very best, ‘access-constrained’ funds, while reserving direct investing only to those cases where the BBB is managing funds on others’ behalf, such as NSSIF and SovAI.

This successor institution should require funds it backs to invest in the UK in proportion with the BSC’s LP stake, thereby encouraging both domestic investment and exposure to global opportunities. Portfolio data should at minimum underpin a basic CRM for use across the state, if not a real-time intelligence service for national procurement, regulatory and industrial strategy.

Finally, fixing pay and autonomy will be a key litmus test of intent: if the state does not seriously compete for talent, any attempt to build a sovereign capital allocator will remain entirely rhetorical.

British Sovereign Capital should focus on being an LP, while only investing directly in exceptional cases

There has never been a strong case for extensive BBB direct investing, which is usually a recipe for adverse selection, especially when the best investors and former operators can’t be attracted into a slow-moving, low-paying bureaucratic body (as it is seen). Direct investing also magnifies many of the challenges that HMT will be most worried about, such as investment risk, moral hazard and market distortion.

Instead, as well as avoiding these problems, focusing on a portfolio of proven, specialist fund managers to invest on BSC’s behalf would:

- bring leading funds and startups into scope, improving BSC's ability to capture value and accelerate strategic innovations in critical sectors;

- strengthen venture firms themselves, compounding the value of their network and experience to companies – including signalling startups’ quality and conferring their funds’ brand and legitimacy on them, in a way that the BBB could never do itself; and

- diversify risk and create a clean feedback mechanism: the BBB commits to funds, monitors their returns and whether they stayed on-thesis, and then decides whether to re-up or not for the next fund. (This will require a more ruthless approach than that for which the BBB is currently known.)

As we and others have set out elsewhere, concerns about a market failure in today’s venture ecosystem – whereby today’s funds and startups merit greater funding than institutions are providing – may be overstated. But today’s startup ecosystem is a lagging indicator. Looking ahead, we may need to unlock much more capital to take on new, more capital-intensive problems in sectors such as defence, energy, manufacturing, bio, supply chains, and more. Even without that, it’s also clear that institutional funds in the UK allocate less to private markets in general than their international comparators do, both due to structural fragmentation and cultural risk-aversion. The BBB can and should play a role in fixing this, which would help to tackle the UK’s incredibly shallow LP base: a 2021 report from Collective Equity found that only 17% of LPs are repeat investors into funds, while only 4% invested in more than one fund. As a result, it’s no surprise that the British Business Bank remains the largest LP in UK VC, providing nearly a fifth of all capital invested across UK VC between 2022-2024:

Table 3: The BBB is the largest LP in UK venture

BBB market share (2022-2024) | % of deals | % of investment value |

|---|---|---|

Seed | 16% | 25% |

Venture | 14% | 17% |

Growth | 9% | 14% |

Total | 14% | 17% |

As such, efforts to unlock more institutional funding are worthwhile, especially if the objective is to help pensions and other institutions to better understand the asset class and to build the capability to step in as long term allocators. But two years after the Mansion House Compact, most pensions still lack the capability or conviction to invest in venture, illustrated by many building in-house teams to avoid fees rather than partnering with proven funds. This focus on cost-minimisation demonstrates a lack of understanding or confidence in venture: when the power law is so strong, the game is about getting into winners and capturing the upside, not cost-minimising on fees or focusing on downside risk. When you can only lose 1x your investment but can gain 1000x, institutions shouldn’t focus on shaving 1% off fees, but on allocating to venture funds that have shown they can consistently capture outlier returns.

If UK institutions cannot be won round on this argument just yet – despite the most sophisticated endowments in the US and Canada having benefitted from investing in venture funds for decades – then there may be benefit in the government, via the BBB, being a pioneer. The government is already exploring crowding in pension capital through the British Growth Partnership, which involves a cornerstone government investment, but incredibly this is mostly focused on helping pension funds to make direct investments – a capability in which neither the BBB or pension funds excel.

Instead, focusing primarily on building a best-in-class fund of funds would suit BBB’s capability and skillset, align with a new mandate focused on value capture and strengthening UK funds, and fix a real gap in the market: to ‘put money to work’, large institutions need to deploy large sums into funds, but they also generally prefer not to be the largest investor in the fund. Necessarily, this means that £25m-£50m tickets often only ‘fit’ into much larger funds (e.g. £250m+). Given that most UK venture funds are much smaller than this, there is just a major structural barrier to major institutions investing in UK venture funds. As such, a larger fund-of-funds, which can pool larger tickets from institutional investors, is a solid way to absorb institutional capital and allocate to smaller funds from there.

One useful precedent could be the BBB’s early stage fund-of-funds scheme, Enterprise Capital Funds (ECF), which has proven effective at both crowding in private investors and creating an on-ramp for new fund managers. Under this model, the BBB crowds in private capital by capping its own returns, effectively giving other investors a form of leverage. For example, the BBB might cornerstone 60% of an emerging manager’s fund but only take 20% of the profit (effectively just claiming back its investment principal, in real terms). So after the fund managers’ own carry (typically 20%), private investors contributing just 40% of the investment principal would receive 60% of the profit.

While this gearing mechanism is currently only used for smaller, early stage funds, it could be extended to later stage funds. Doing so would shift the market signal: instead of BBB involvement implying that a fund couldn’t attract ‘better’ private investors, it would be adding significant value – by crowding in more private capital at scale – that would attract top-tier funds who ordinarily would avoid the BBB.

An alternative and/or additional solution could be to temporarily cover the VC funds’ management fees that pension funds would otherwise pay, at least for an initial fund cycle and in exchange for an adjusted split of carried interest returns. This would test the argument that fees are a barrier to deployment, while accelerating institutions’ familiarity, confidence and capability to invest in venture, before being removed for future fund cycles.

SovAI must be built for velocity. Full autonomy may be the only way

SovAI, the government’s new £500m vehicle to ‘build and harness the AI capabilities’, is a test case for the state’s ability to invest both strategically and directly into companies (rather than funds). It will fail if a) it is run simply as a DSIT policy unit, b) it remains reliant on a slow-moving BBB to manage the back-end administration, and c) it cannot attract and empower a respected investor to build the rest of the team.

In effect, DSIT should apply the lessons of two of the most successful experiments in state capacity of the last few years: the AI Security Institute (AISI) and the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) showed that institutions focused on exponential, asymmetric outcomes can be built within government, but to succeed they require extraordinary autonomy, exceptional leadership and unique, distinct cultures with a high tolerance for risk.

To that end, SovAI must be clearly structured as a fund, just with the government as sole LP. Some of the £500m could be put aside into a non-commercial grants programme, but the fund structure is important for the rest because it introduces clear incentives, feedback loops and discipline around value creation, rather than SovAI operating as just another policy unit with a funding pot where it risks pursuing a loose collection of projects which may be more distortive than productive.

Yet today there is ambiguity over its autonomy, mandate, investing criteria (stage, sectors, geography) and how it achieves (or trades off) its economic growth and national security objectives. To hit the ground running, this must all be resolved well in advance of April 2026, when it receives its initial £500m capital.

As Lawrence Lundy-Bryan describes, SovAI is an initiative that only works if it truly has velocity and autonomy, because windows to create and capture value open and close rapidly as AI accelerates:

A Specific Theory of Sovereign AI, Lawrence Lundy-BryanThe Sovereign AI Unit or any other institution must make decisions in 2 weeks (why not 1 week?) and deploy capital in 2-4 weeks. This isn’t about efficiency. It’s about whether investments arrive in time to go out and win fast-moving markets. But operating at this speed with taxpayer money inverts every normal government instinct.

But this moment is different…the theory of failure isn’t investing in the wrong things and losing money. It’s being too slow to invest in the right things and missing the window where those investments create value.

If SovAI’s mandate is to make investments both to secure Britain’s strategic interests and to capture value, it needs to be able to move quickly to find and partner with the early movers who may end up setting global standards. If it wants to take equity stakes in companies or funds, it not only needs to move quickly to keep up with other investors’ speed, but also to overcome many founders’ and investors’ (reasonable) suspicion of public money and have a compelling offer to invest in competitive deals. The government cannot simply turn up and expect to be able to invest when it wants to.

Instead, SovAI’s offer likely may need to include genuine influence over compute, procurement and regulatory levers, even if they are not under its direct control. It must be empowered to operate globally and build stakes in key AI companies wherever they are, not only UK companies; it needs a reliably quick process for deal execution and fund management to keep up with others’ speed; and it needs to be able to attract and employ investors with compensation packages far outside the usual civil service pay bands.

Britain’s need to build its stake in the AI value chain has never been clearer. A strategic venture investor is potentially a major part of the toolkit. But to succeed, the government must empower SovAI to fulfil its potential.

Replace EIS and VCTs with expansions to EMI

Investment incentives, especially EIS and VCT, have outlived their purpose and are now poor value

EIS and VCTs were introduced in the 1990s to stimulate a fledgling venture ecosystem. Now, Britain is Europe’s leading startup ecosystem by far, yet these schemes have been extended and expanded multiple times since their inception, costing approximately £1 billion every year:

Table 4: EIS, VCT and SEIS now cost ~£1 billion a year (sources: Non-structural tax reliefs, Employee Share Scheme Statistics)

EIS (Enterprise Investment Scheme) | VCT (Venture Capital Trust) | SEIS (Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Created | 1994 | 1995 | 2012 |

Income tax relief on initial investment | 30% | 30% | 50% |

Annual investment ceiling | £2,000,000 | £200,000 | £200,000 |

Tax relief on partial or total losses | Yes | No | Yes |

Tax-free dividends | No | Yes | No |

Gains exempt from CGT | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Holding period required | 3 | 5 | 3 |

Average annual cost of Income Tax relief | £558,000,000 | £413,000,000 | £100,000,000 |

Average annual cost of CGT relief | £74,000,000 | n/a | £1,000,000 |

Average annual cost | £632,000,000 | £413,000,000 | £101,000,000 |

Total annual cost | £1,146,000,000 | ||

What may once have been a reasonable policy to derisk a fledgling sector has now effectively become a direct transfer of wealth from everyday taxpayers to fund managers who mostly sell tax relief, not investment upside. This is not VC. It’s a waste of scarce government support.

In theory, (S)EIS and VCT are designed to channel private wealth into early-stage startups by offering generous tax incentives. SEIS (and EIS for individual angels) is still likely worthwhile, without being a major cost to the taxpayer. But as Alex Chalmers analyses in A Parody of Venture, the EIS and VCT schemes in particular have spawned an industry of funds who effectively operate as intermediaries packaging tax relief to investors, often charging high fees while backing modest-return firms that allow investors to bank the tax relief up front and then get their money back later. This is a farce of financial engineering that slows talent reallocation and creates an ecosystem of ‘zombie firms’ who are unable to scale, yet are kept alive by subsidy rather than innovation.

Policy support should now shift from stimulating startups to scaling global winners and compounding their value in Britain. At a time when firms and talent can relocate freely and AI is reshaping value chains, fiscal incentives must reward scaling and domestic value capture, not tax arbitrage.

EMI is a much better incentive to support growth and domestic value capture, but its cliff-edges need updating

One way that the government does incentivise genuinely high-risk, high-reward companies to be founded and scaled in the UK is via Enterprise Management Incentives (EMI). Under EMI, companies can award employees up to £250k in share options. In most cases, employees only pay capital gains tax, while gains are de facto exempt from income tax and national insurance. In principle this is a highly attractive scheme which helps early-stage, cash-poor companies to compete for exceptional talent and increase their odds of success.

But outdated limits – £30 million in assets and 250 FTE employees, unchanged since 2002 – now penalise success, excluding both new companies that launch with major funding rounds and established firms as they begin to scale. In effect, UK startups can quickly go from having a very attractive employment offer at the start of their journey, to having very little to compete. This is increasingly an issue, not only for scale-ups who are seeing real commercial traction and keen to grow their workforce in the UK, but also for the increasing number of early-stage companies now being founded with major early funding rounds over £30m, reflecting the growth of the global venture market.

Redirecting up to £1 billion spent on EIS/VCTs towards expanding EMI (and resourcing British Sovereign Capital) would ensure the benefits of companies’ success are more widely felt by the full labour force and also incentivise companies to deepen their economic commitment to the UK by building and scaling their operations here, at a key inflection point for the business.

Crucially, EMI is remarkably fiscally-efficient: the government can encourage far more employers and employees to locate, hire, and scale in Britain than it ever ‘pays out’ to, because most technology companies do not reach a liquidity event and therefore don’t trigger EMI relief.

Table 5: Most employees granted options don't exercise them

For every £1bn: | Companies | Employees |

|---|---|---|

Redeeming participants | 4,666 | 23,256 |

No-cost participants | 6,049 | 77,907 |

Total | 10,715 | 101,163 |

While the thresholds were a reasonable way to focus EMI on startups when first introduced, significant time has since passed and – in line with a renewed focus on supporting scale and domestic value capture as primary objectives of government support for venture – these should be updated. Notably, while any change made today would immediately support companies making hiring decisions and granting options, HMT would not have to ‘pay’ for this until at least 5-7 years when these additional options are exercised.

Three illustrative ways to expand EMI

The easiest option would be to increase the current thresholds, reflecting the significant growth of the venture ecosystem and company fundraises – particularly at the highest end of this power law-defined market – since the thresholds were last updated in 2002.

Additionally, HMT could introduce a new scheme focused specifically on scale-ups which removes the asset limit entirely (which is, ultimately, priced into share options) and expands the employee threshold significantly. Given that options for later stage companies are more likely to be exercised, this could be offset by taxing gains at a higher rate of CGT, e.g. 32%, in line with the planned increase to tax on carried interest for investment funds. Alternatively, and more ambitiously, HMT could bring EMI in line with the US equivalent, QSBS (Qualified Small Business Stock), which exempts employees from capital gains tax on the first $15 million of gains.

Table 6: Three options to expand EMI

EMI Options (Illustrative) | Current | Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

EMI | EMI Expansion | "EMI Plus" | QSBS-style CGT exemption | |

Company asset limit | £30,000,000 | £120,000,000 | n/a | n/a |

Company FTEs limit | <250 | 250-500 | 500-2500 | 250-500 |

Company share option pool value % | 10% | 10% | n/a | n/a |

Company share option pool value limit | £3,000,000 | £12,000,000 | £20,000,000 | £20,000,000 |

Employee share option grant limit | £250,000 | £250,000 | £250,000 | £250,000 |

Capital gains tax rate | 24% | 24% | 32% | 32% |

Employee CGT-exempt gains limit | n/a | n/a | n/a | £5,000,000 |

Modelled RoI | 2.65x | 1.84x | 1.46x | - |

Acknowledgements

Thanks in particular to Ezra Cohen, Pedro Serôdio and Matthew Stubbs for their analytical support, and to many, many others for their invaluable input and insight. All views, errors, and omissions are the sole responsibility of the author.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]