Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Background

- 3. The flaw in the current formula

- 4. Our proposal

- 5. A realistic solution

- 6. Authors

- 7. Appendix

Summary

The ‘triple lock’ on state pension growth has become an important way of ensuring that pensioners, many of whom are in the lowest income brackets, continue to receive a fair income. However, the formula in its current form will accrue unsustainable anomalies over time. Fixing the formula is critically important to protect the triple lock from future suspensions.

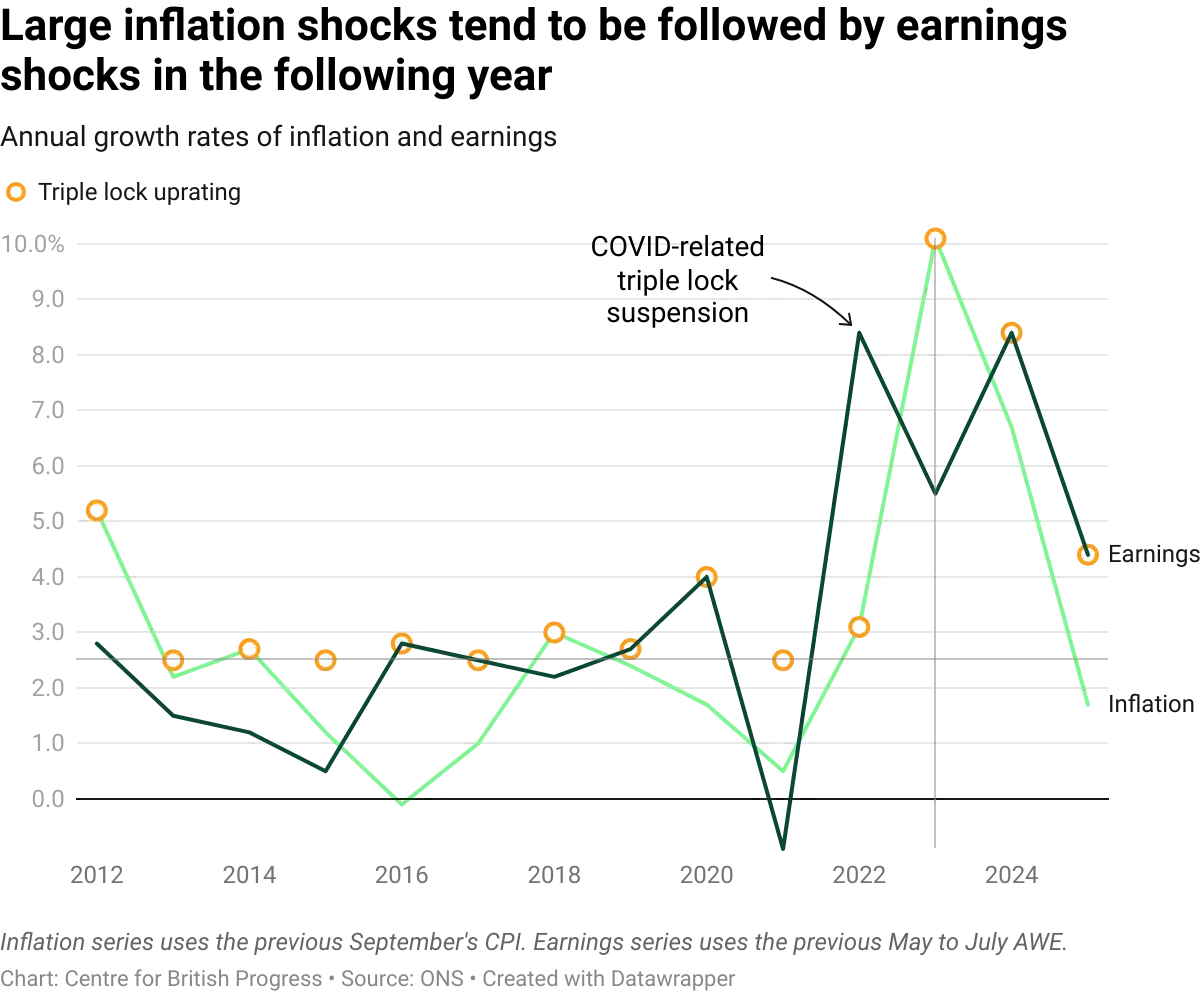

The current pensions uprating scheme, introduced by the Coalition government in 2010, requires that pensions annually increase in line with the highest of nominal earnings growth, inflation or 2.5%. This formula is fundamentally flawed. It is guaranteed to ‘double count’ price increases, because a spike in inflation one year is typically reflected in an increase in wages the next, an increase which is added to pensions twice over. This is unfair, unnecessary, and costly. Indeed, the previous Government had to suspend the formula after Covid for precisely these reasons.

Over time, the result of this broken formula is that pensions rise much faster than earnings, consuming an ever-escalating portion of the national economy and budget. Having cost around three times more than initially forecast, the OBR now estimates that the triple lock alone will push up state spending by around 1.6 percentage points of GDP over the next 50 years. In 2025, this proportion of GDP is equivalent to £46 billion in public spending. This is an enormous sum, roughly equal to the annual budgets for waste management, prisons, local roads, local public transport, school capital investment, fire protection, medical research and street lighting combined.

It is unsustainable for pensions to forever receive ‘double dip’ treatment every time earnings and inflation spike. On this trajectory, pensions would (hypothetically) eventually consume all of GDP – something which no government would allow to happen. Eventually, a government will have to reform or ditch the triple lock. The only question is how and when the policy will change. We argue that the formula should be fixed, which is strongly preferable to abandoning the triple lock.

The Government has committed to retaining the triple lock. To do so, it should fix the formula to make the policy more robust and sustainable, while keeping all three locks.

We propose changing the way the triple lock is calculated, so that two of the “locks” reflect changes over a ten year period, rather than just the last 12 months. The changes are summarised in the table below:

Current calculation | Our proposed calculation | |

1. Earnings lock | Earnings growth over last 12 months | Amount required to match earnings growth over last 10 years |

2. Inflation lock | Inflation over the last 12 months | Inflation over the last 12 months |

3. 2.5% lock | 2.5% | Amount required to match annual 2.5% growth over last 10 years |

Our modelling suggests that this will reduce the trajectory by £6.2 billion annually by 2030, and over £36 billion per annum by 2040, while ensuring that the triple lock is protected.

Background

The 2010 budget introducing the triple lock described the policy as follows: “In the last Parliament, the basic State Pension was uprated by the higher of prices or 2.5 per cent. This Government will uprate the basic State Pension by a triple guarantee of earnings, prices or 2.5 per cent, whichever is highest, from April 2011.” The budget did not set out any definition for earnings or specify the index that would be used for its measurement.

This agnostic approach to measuring earnings long predates the introduction of the triple lock. The Social Security Administration Act 1992 requires that “The Secretary of State shall in each tax year review [the basic state pension and other forms of social security]…in order to determine whether they have retained their value in relation to the general level of earnings obtaining in Great Britain”. In 2007, then-Pensions Minister James Purnell specifically explained that it was advantageous for the legislation not to specify which metrics would be used as “such measures change over time… and it is important to leave the Government of the day with flexibility in that regard.”

Sure enough, the standards used for measuring earnings and inflation have changed on multiple occasions, including over the lifetime of the triple lock. Three examples are of particular relevance:

1. When the coalition government introduced the triple lock, they announced from the outset that the measure of prices would not be consistent. The 2010 budget stated: “CPI will be used as the measure of prices in the triple guarantee, as for other benefits and tax credits. However, to ensure the value of a basic State Pension is at least as generous as under the previous uprating rules, the Government will increase the basic State Pension in April 2011 by at least the equivalent of RPI”. As RPI was higher than CPI at the time, the basic State Pension was increased by RPI in April 2011 but CPI has been used as the relevant metric in every year since.

2. Shortly before the introduction of the triple lock, there was minimal reaction when the measure of earnings was changed in January 2010 from the Average Earnings Index (AEI) to the Average Weekly Earnings (AWE). There are multiple significant differences between the two measures; for example, AEI makes no attempt to account for earnings changes in small businesses (<20 employees) whereas AWE does. This could produce marked differences in their results. For example, in 2010, AEI stood at 2% while AWE was only 1.3%.

3. Rather than fixing the measuring sticks, the Conservative government opted for a wholesale suspension of the triple lock in 2022-23. This effectively left in place a double lock of inflation and 2.5% for that year. That suspension of the triple lock is an important precedent, in part because it highlights how its future would be threatened if public finances worsen.

The flaw in the current formula

The fundamental flaw with the current method of measuring earnings growth is that the use of a single year metric injects extreme, expensive, and unfair volatility into the system, which leads to double counting. The years of 2023 and 2024 demonstrated this problem. In 2023, pensions were uprated in line with the 10.1% rise in CPI. In 2024, pensions were uprated by a further 8.5%, the recorded measure for annual earnings growth, although this increase in nominal earnings was largely reflective of the inflationary spike which had already been accounted for in the previous year.

This short-term emphasis is exacerbated by the specific way in which earnings are measured. By convention, earnings growth is calculated with reference to recorded earnings in the May-July period. By focusing on a specific period of the year, the volatility of earnings is only heightened. For example, the chronology of the pandemic meant that economic activity was particularly constrained in May-July 2020. In June 2020, the Resolution Foundation warned that as a result, they expected “more exaggerated fall-then-rise in earnings for triple lock purposes than implied by the Bank’s estimates for annual changes over the whole (calendar) year”. Sure enough, the recorded figures for earnings growth in 2020 and 2021 were -1% and 8.3%, a spike that ultimately led to the suspension of the triple lock.

By using a longer term metric, the state would smooth out volatility, reduce the double counting and make the future trajectory of State Pension spending more predictable, ameliorating or eliminating the problems detailed above.

Our proposal

We propose future-proofing the triple lock by increasing the period over which the earnings lock and the 2.5% per year floor are measured to avoid double counting. This will ensure that pensions always keep up with both inflation and earnings, but it will avoid the ‘twice over’ flaw in the current formula.

Current formula | Our proposed formula | |

1. Earnings lock | Earnings growth over last 12 months | Amount required to match earnings growth over last 10 years |

2. Inflation lock | Inflation over the last 12 months | Inflation over the last 12 months |

3. 2.5% lock | 2.5% | Amount required to match annual 2.5% growth over last 10 years |

Under the new system, pensions would be uprated by the greater of the rate of inflation in the previous year or a ‘keep up’ factor. This factor is the amount necessary to ensure that pensions have kept up over the preceding decade with (a) the growth in average earnings and (b) an increase of 2.5% a year, whichever is greater. There is also a fail-safe where if both the rate of inflation and the ‘keep up’ factor are negative, pensions do not nominally decrease. A worked example is detailed in the Appendix to this paper.

This change would reduce the extreme volatility in the formula and ensure that the growth in pensions remains sustainable over time, yet it would also retain all three components of the triple lock and ensure that pensions keep up with earnings growth.

The expectation in our modelling is that this would save £6.2bn a year in 2030, although the precise savings would of course depend on future inflation and earnings growth. The improved future fiscal profile should also reduce the Government’s borrowing costs, thereby ensuring additional savings for the Exchequer in the short and long term. This will allow the Government to make further critical investments in infrastructure to improve growth and raise earnings, feeding through into higher pensions.

A realistic solution

There will be those who argue that this proposal goes either too far or not far enough.

Turning first to the latter, some would do away with the triple lock entirely (or go even further by freezing the state pension for a period of time). However, the triple lock has more merit than many would argue. From the start of the state pension until the introduction of the triple lock, the uprating mechanism variously followed inflation, earnings or a combination of those factors. At other times, the amount was dependent on ad hoc changes, falling in real terms before undergoing a sharp correction. The triple lock ultimately developed as a means to provide pensioners with a stake in rising standards of living while also guarding against the possibility of a real decline in its value (with the 2.5% component ensuring that the rise was always substantive).

Crucially, any proposal for reform also has to account for the reality that the current government has made commitments to retain the triple lock. The approach outlined here is the most effective means for the government to protect that pledge by ensuring that it remains sustainable.

Then there are those who agitate against any reform to the triple lock formula. This group points out that, while pensioner poverty has receded to the point where it is less prevalent than in other age groups, it remains the case that around one in six pensioners are living in poverty. This is a vitally important point. But the best way to ensure that those pensioners are helped through the triple lock is to ensure that it will be sustained. Given the increasing pressures on public finances the best way of doing that would be to execute the reforms outlined in this paper, retaining the important principle of the triple lock while keeping pensions on a sustainable trajectory.

Appendix

Worked example

Hypothetical pension uprating in 2030:

- Inflation in 2029: 2.8%

- Earnings growth in 2029: 4%

- Pension growth 2020-29: 30%

- Earnings growth 2020-29: 34% (Roughly an average of 3% per year)

- Keep-up factor: max(10yr wage growth, 2.5%10)10 yr pension growth= max(134%, 128%)130%=3.1%

- In this case, because earnings have risen faster than 2.5% per year, it is earnings growth that is the binding factor for uprating.

- Pension growth: max(inflation, keep up)=max(2.8%,3.1%)=3.1%

- Original triple lock pension growth: max(inflation, earnings growth, 2.5%)=4%

Modelling detail

To model the impact of our proposed reform we used a Monte Carlo simulation with inflation and earnings growth as independent, AR(1) processes. These were fitted to the historical inflation and earnings growth the UK has seen since 2000. We conducted a number of statistical tests to validate that this was a reasonable model of inflation and wage growth. In each simulation run we compared the pension increase that would have resulted under the triple lock with the increase that our proposed reform would deliver. The £6.2bn annual saving reported above is the nominal average saving across all of these runs in 2030.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]