Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Background

- 3. Carbon Price Support is no longer fit for purpose

- 4. Britain needs to electrify

- 5. How cutting CPS reduces bills

- 6. The impact of removing CPS

- 7. Authors

Summary

- Carbon Price Support (CPS) was introduced by the Coalition Government with the aim of encouraging the green transition, and removing coal power from the grid, by taxing fossil fuels used to generate electricity.

- In reality, CPS makes the transition harder: by making electricity more expensive, households are less likely to move away from gas (for heating) and petroleum fuels (for cars).

- Meanwhile, CPS offers a poor deal for the taxpayer. CPS increased electricity costs by more than £3.50 for every £1 it generated for the Exchequer in 2024.

- This means that households and businesses experience a lot of pain without obvious benefit for decarbonisation, and very little revenue generation for the Treasury.

- Abolishing or zero-rating CPS would reduce bills by £1.3 billion for households, businesses and the NHS, while supporting the switch towards greener, electrified heating and transport.

Background

The UK (excluding Northern Ireland, which has a different regime) is highly unusual in having two different carbon costs for electricity generation, a legacy of decisions made by the Coalition Government:

- UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS): a cap and trade scheme, where participating sectors must acquire carbon allowances to cover their carbon emissions. Electricity generators participate alongside aviation and energy intensive industries, buying allowances in Government auctions or secondary markets. The UK ETS took effect from 1st of January 2021, replacing the EU ETS following the UK’s departure from the European Union . The current carbon price of the UK ETS is around £57 per tonne vs. around £69 per tonne for the EU ETS. As per Article 392 of the Trade and Cooperation agreement, the UK must have in place an effective system of carbon pricing.

- Carbon Price Support (CPS): This is an additional tax on fossil fuels used for electricity generation. It was introduced in 2013 to help increase the level and certainty of carbon prices in the UK (as the ETS price can be volatile). It is applied at the point that fossil fuels are delivered to a generating station. The current CPS rate is £18 per tonne, and has been frozen since April 2016.

Carbon Price Support is no longer fit for purpose

CPS has outlived its original intended purpose. Its designers hoped that higher carbon prices would lead to a substitution of coal generation with less carbon-intensive gas-fired electricity. This has been successful, and the UK has closed its last coal-fired power station.

The original impact assessment for CPS is from December 2010. Carbon prices under the EU ETS had been volatile in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, peaking at around £26 per tonne in 2008, then falling to below £9 per tonne in the first quarter of 2009. Adding an extra carbon tax (CPS), the Treasury argued, would provide greater predictability and stability to the cost of carbon. Higher and more consistent carbon costs would in turn increase the incentives for investment in low-carbon generation, such as renewables and nuclear power.

The facts have changed substantially since the original policy was introduced. We argue that now is the time for the Government to consider removing CPS, or setting the rate to zero for the remainder of the Parliament—to cut bills and encourage electrification.

Britain recently closed its last coal power station

30th September 2024 marked the end of coal’s use for electricity generation in the UK, with the closure of Ratcliffe-on-Soar. There is no longer any risk of coal being burned due to the removal of CPS.

Electricity generated from a coal power station is about twice as carbon intensive as electricity from a combined cycle gas turbine. Increasing carbon costs for electricity generators helped make coal more expensive relative to gas, driving it out of the market. Now that that job is complete, and there is no current large-scale alternative to gas for dispatchable power, CPS serves only to drive up bills.

New generation assets have support mechanisms other than carbon prices

At the time of consultation in 2010, new large scale renewable energy projects were supported by the Renewable Obligation (RO) scheme. The scheme awards generators a number of certificates per MWh of generation, which have an RPI linked buyout price. In addition to the value of Renewable Obligation Certificates (ROCs), generators could sell their electricity on the wholesale market or via a power purchase agreement. Higher carbon prices increased the wholesale price, adding extra financial support to renewable generators.

Since the RO scheme closed to new entrants in 2017, new renewables projects have been built under the Contracts for Difference (CfD) model, which effectively gives generators an (inflation linked) fixed ‘strike price’ for the first 15 years of their operations. If the market reference price is above the CfD strike price, then the generator pays back the difference and vice versa. This means that CfD generators are largely insulated from wholesale prices.

The duration of CfD contracts has recently been extended to 20 years for the upcoming allocation round, and onshore wind projects are now eligible to bid for repowering under a CfD at the end of their operative lives. This means that wholesale market prices have become even less relevant for the economics of CfD generators and removing CPS will not impact the delivery of future renewable power.

New nuclear projects are also insulated from the wholesale market and thus CPS. Hinkley C is being built under a 35 year CfD and Sizewell C is incentivised by the Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model, where investors will receive a regulated rate of return.

New generation projects now have greater predictability of returns via CfDs and RABs. The UK ETS would continue to provide support to generators in the post CfD portion of their lifespan.

Britain needs to electrify

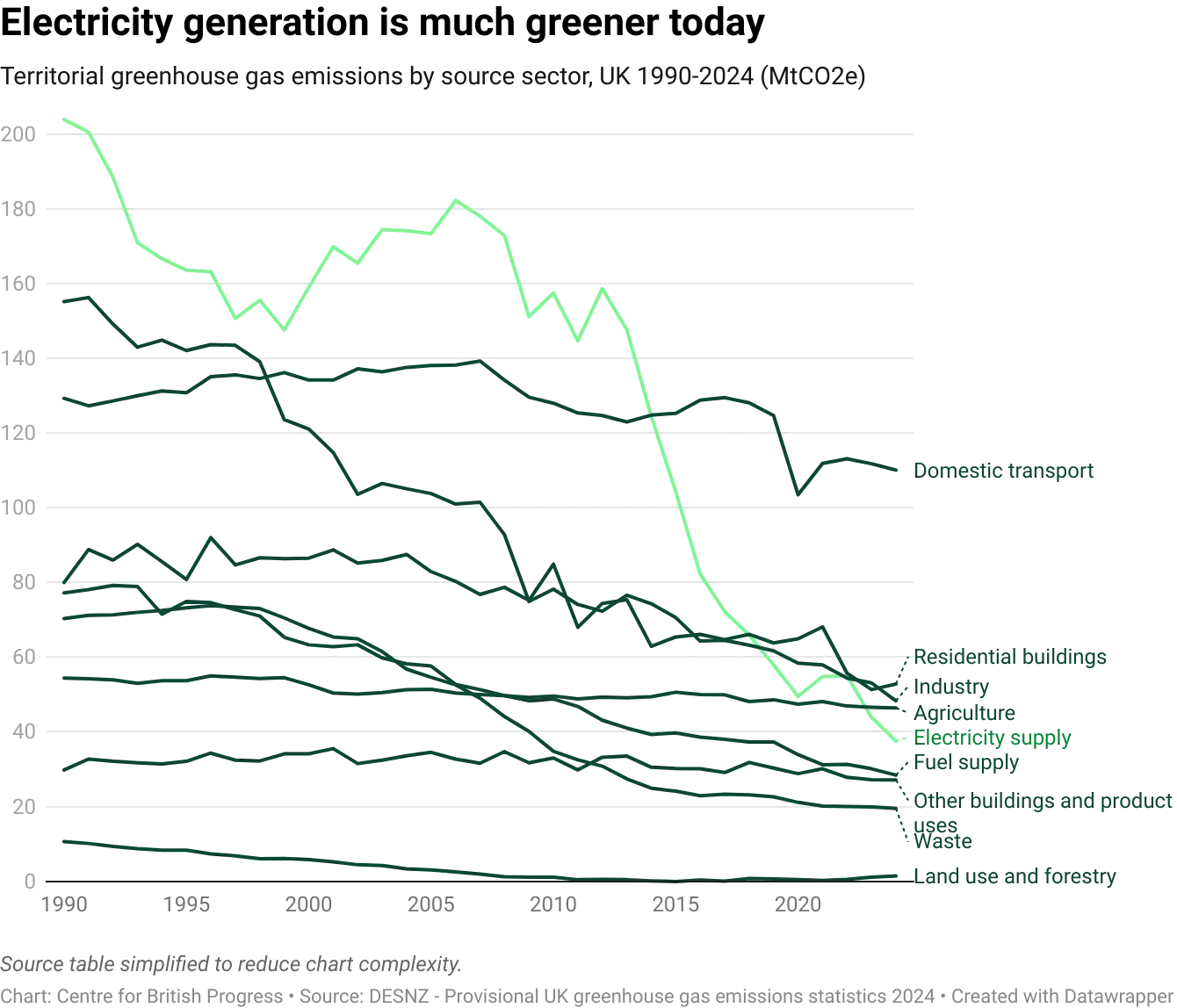

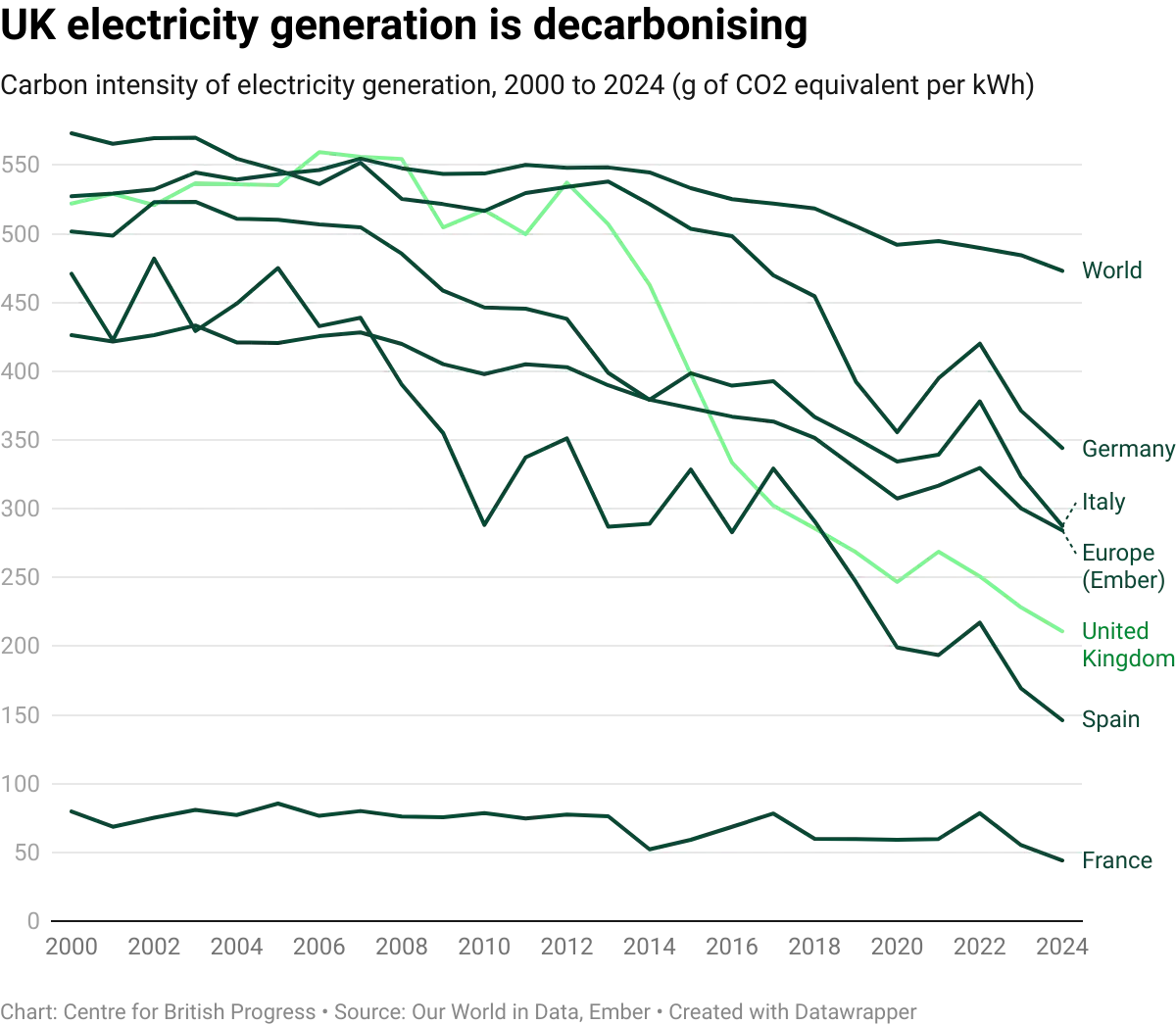

In 2004, the electricity supply sector was the largest source of UK territorial greenhouse gas emissions, comprising 24.6% of the total. By 2024, emissions from electricity supply had fallen by 78% and now comprise just 10% of UK territorial emissions.

To make further progress towards Net Zero, we must decarbonise much more than just electricity generation. Activities such as heating and cooking in residential buildings (14% of territorial emissions) and domestic transportation (30% of territorial emissions) will need to be electrified, via technologies such as heat pumps and electric vehicles.

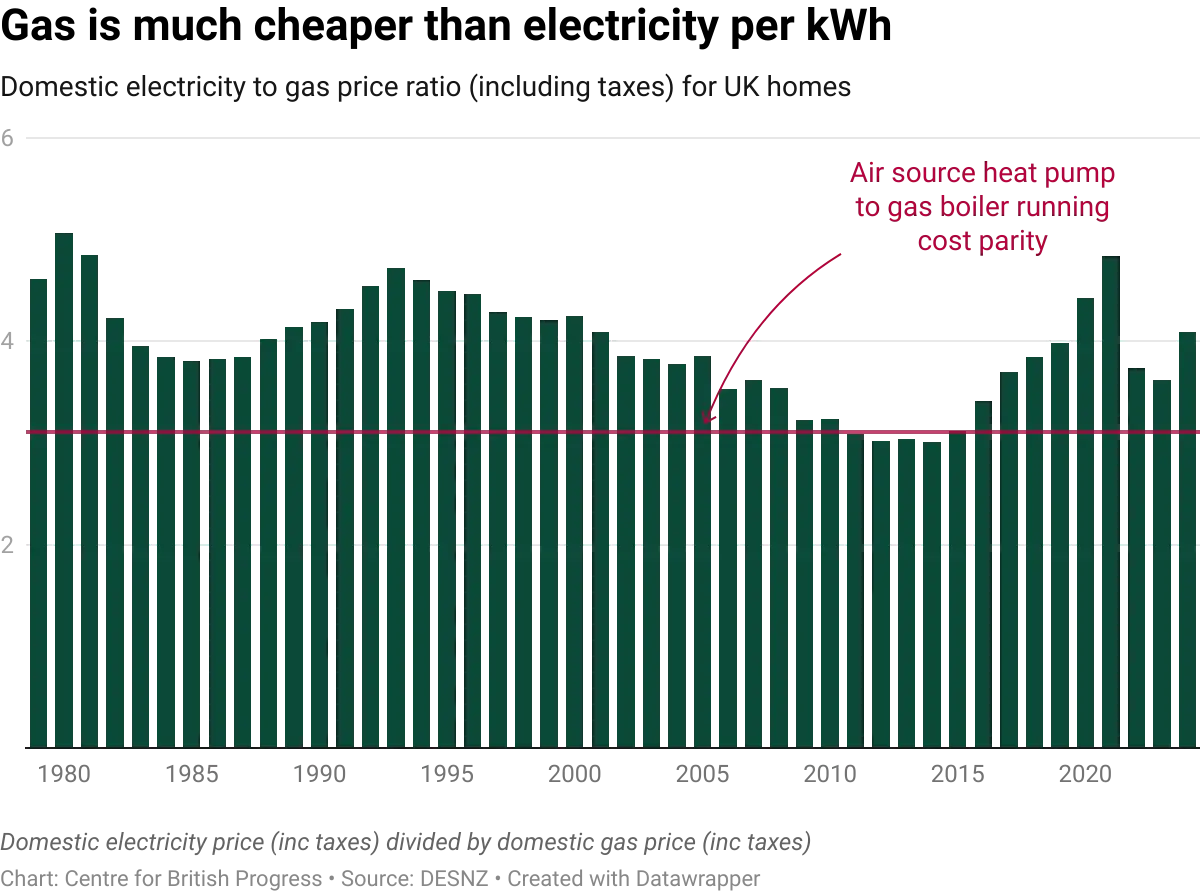

High electricity prices hamper this electrification ambition. For example, a domestic heat pump might use one third the purchased energy to heat a home as a gas boiler. But in 2024 domestic consumers paid about four times more per kWh for electricity than gas. This means that green, electrified heating in Britain is, currently, more expensive than using fossil fuels. High electricity bills mean that consumers can’t make the swap to greener heating economically.

Air source heat pump to gas boiler running cost parity indicator assumes a seasonal performance factor of 2.8 for air source heat pumps and 90% efficiency for a gas boiler.

Removing CPS would reduce consumer electricity bills, helping shift the balance towards electrification.

Clean Power 2030

As well as the Government’s ambitious electrification targets, and binding net-zero mandate, it must also meet its Clean Power 2030 ambitions. This means that by 2030 the UK must, in a typical weather year:

- Produce at least 95% of all GB generation using clean sources;

- Produce at least as much electricity as GB consumes in total from clean sources; and

- Ensure that the carbon intensity of GB electricity generation is well below 50g CO2 equivalent per KWh.

Almost all of the ‘non-clean’ generation on the UK grid is gas. Achieving Clean Power 2030 requires rapid deployment of new generation and transmission infrastructure. Building this infrastructure does not hinge on the wholesale price of electricity: electricity producers are offered a contract-for-difference (CfD) or regulated asset base (RAB), and transmission developers are paid a regulated return on investment. This means that removing CPS will not impact the Government’s ability to deliver the infrastructure needed for Clean Power 2030.

Given the short run marginal costs of gas power stations are materially above those of clean technologies such as wind, solar, hydro and nuclear, we don’t believe that reducing the marginal costs of gas generation by c. £6.60 per MWh (the impact of CPS) will result in significantly higher gas dispatch volumes to service British electricity demand.

One area that will require careful consideration is periods of net export. Britain is connected to the continent by a series of interconnectors, meaning that, in times of low wind and solar output, it is possible for gas to be burned in Britain to supply consumers in, say, Denmark. Modelling from the National Energy System Operator (NESO) assumes that British carbon prices will be significantly higher than those on the continent in 2030, meaning that British gas generators would never be cost competitive with European power plants. This is relevant for meeting the first pillar of Clean Power 2030: keeping gas under 5% of total GB generation.

Whilst NESO’s work makes clear that ‘other options [than CPS] could achieve similar ends’, the Government could preserve its optionality by ‘zero rating’ CPS rather than abolishing it. This would provide immediate relief to bill payers now but leave open the possibility of reapplying CPS in 2029/30 to help meet CP2030.

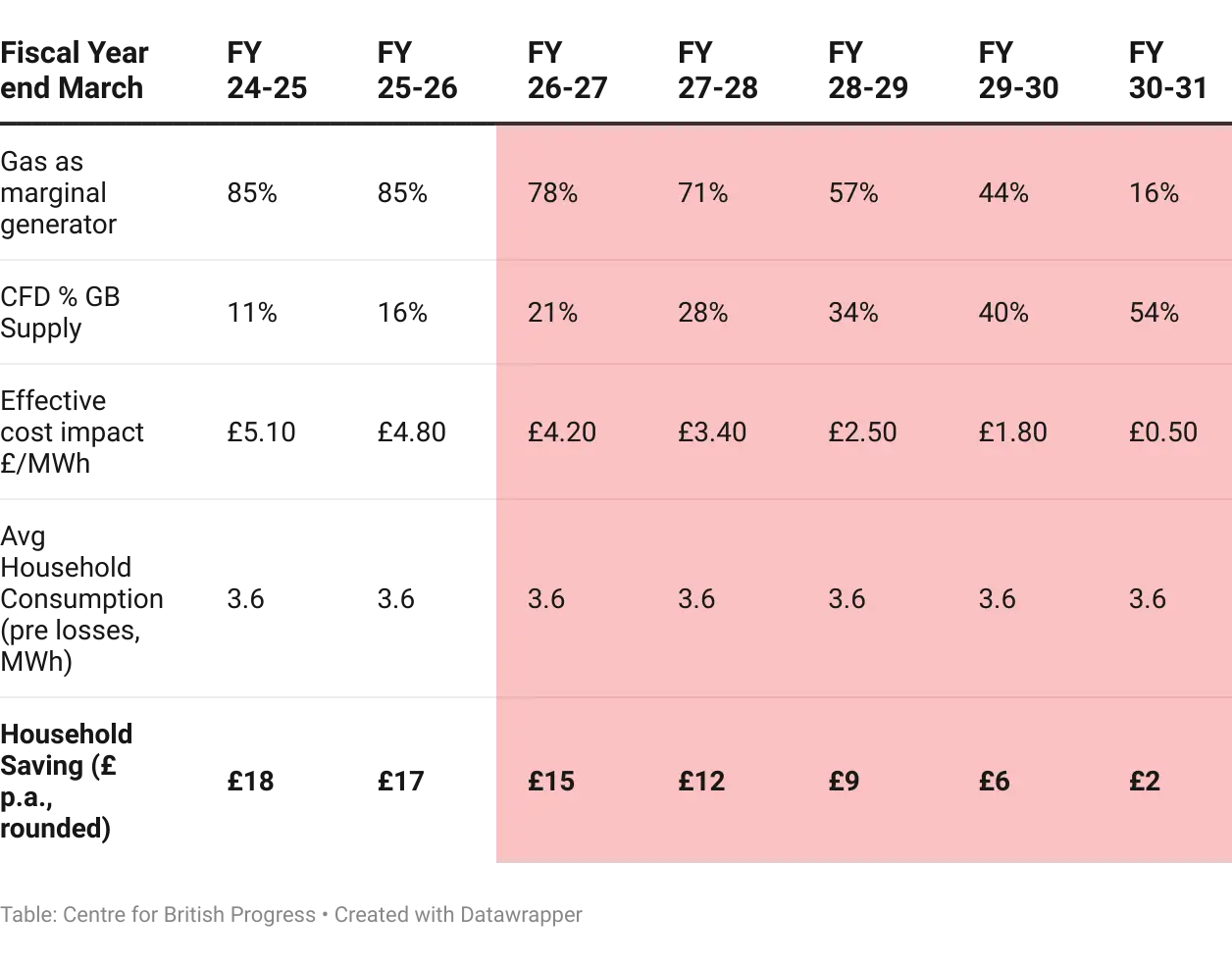

Our modelling suggests that the percentage of electricity supplied by CfD supported assets will continue to rise, with such generators providing over 50% of GB supply by 2030. This means that, crucially, the bill impact of removing CPS is highest now. Re-introducing CPS later (if necessary) would not be felt by consumers as much as its relief would today.

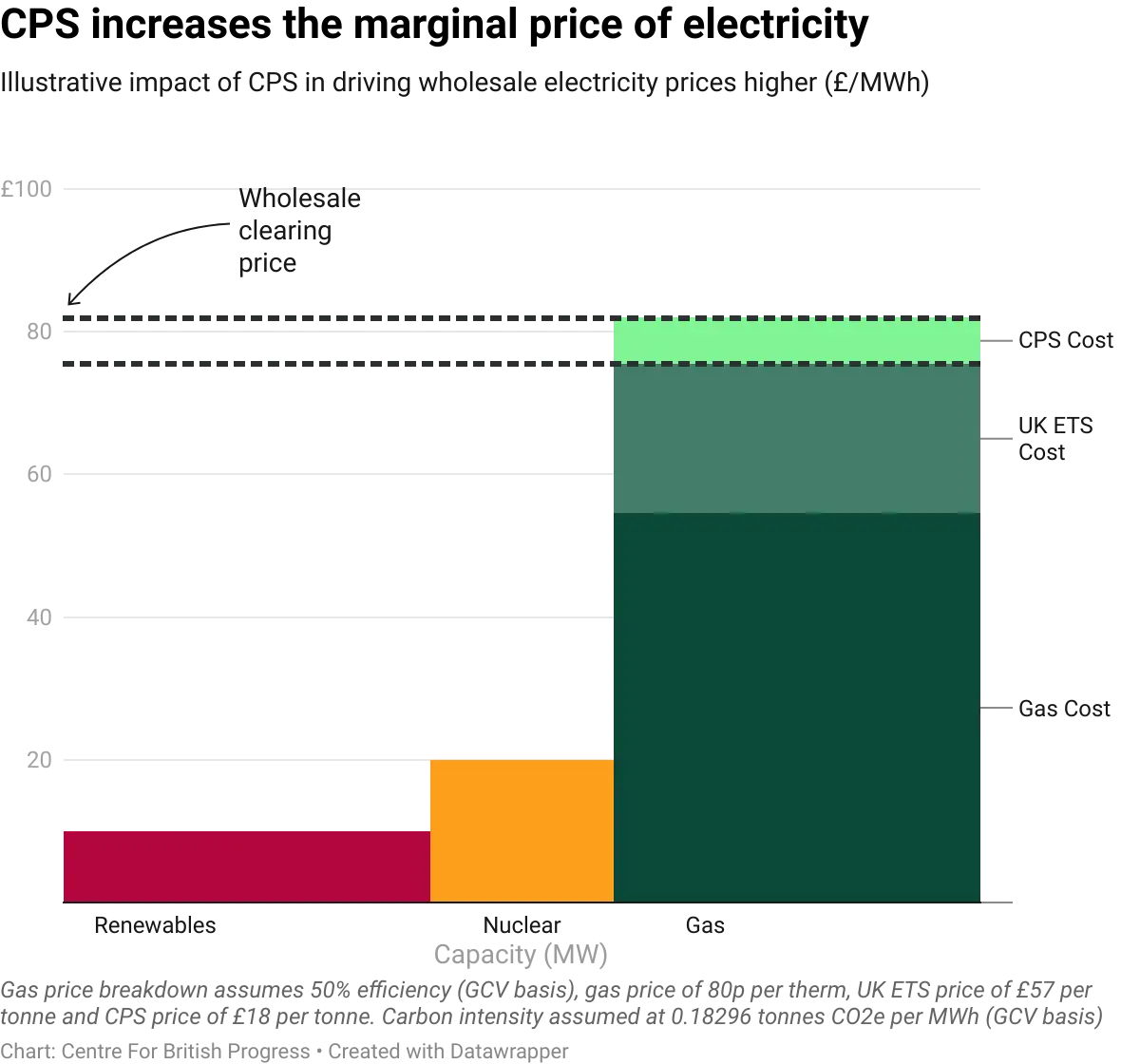

How cutting CPS reduces bills

The day ahead electricity market in Great Britain is based on a marginal pricing system. In each half hour settlement period, the market clearing price is set by the most expensive source of electricity required to meet demand. In the UK, the vast majority of the time, this is a gas power station. CPS increases the marginal generation costs of a gas power station, and thus drives up the wholesale price.

We estimate that CPS cost of £18 per tonne adds around £6.60 of carbon costs per MWh of electricity that is generated by a typical gas power plant in Britain. Whenever gas acts as the most expensive marginal generator, the clearing price in the market will be driven up by this £6.60 per MWh cost increase.

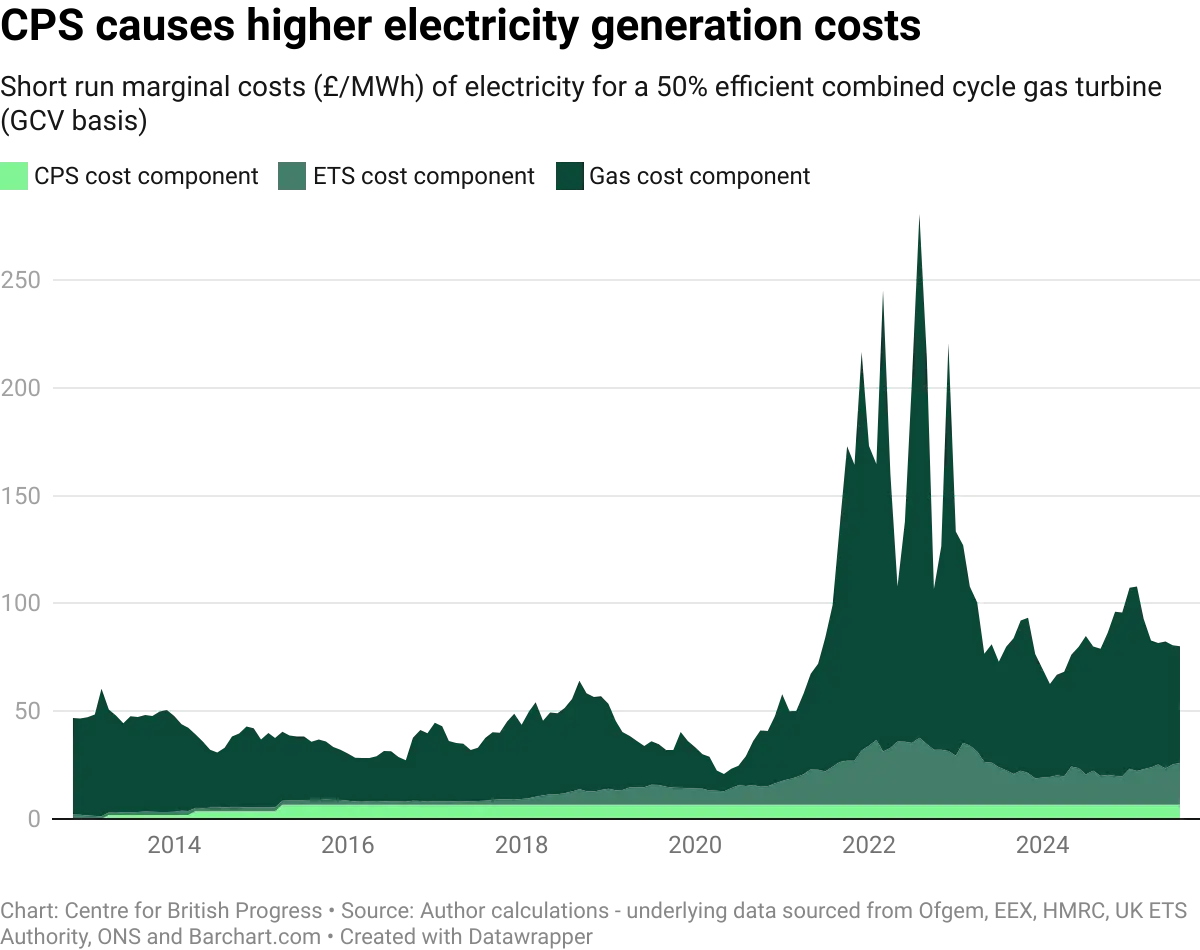

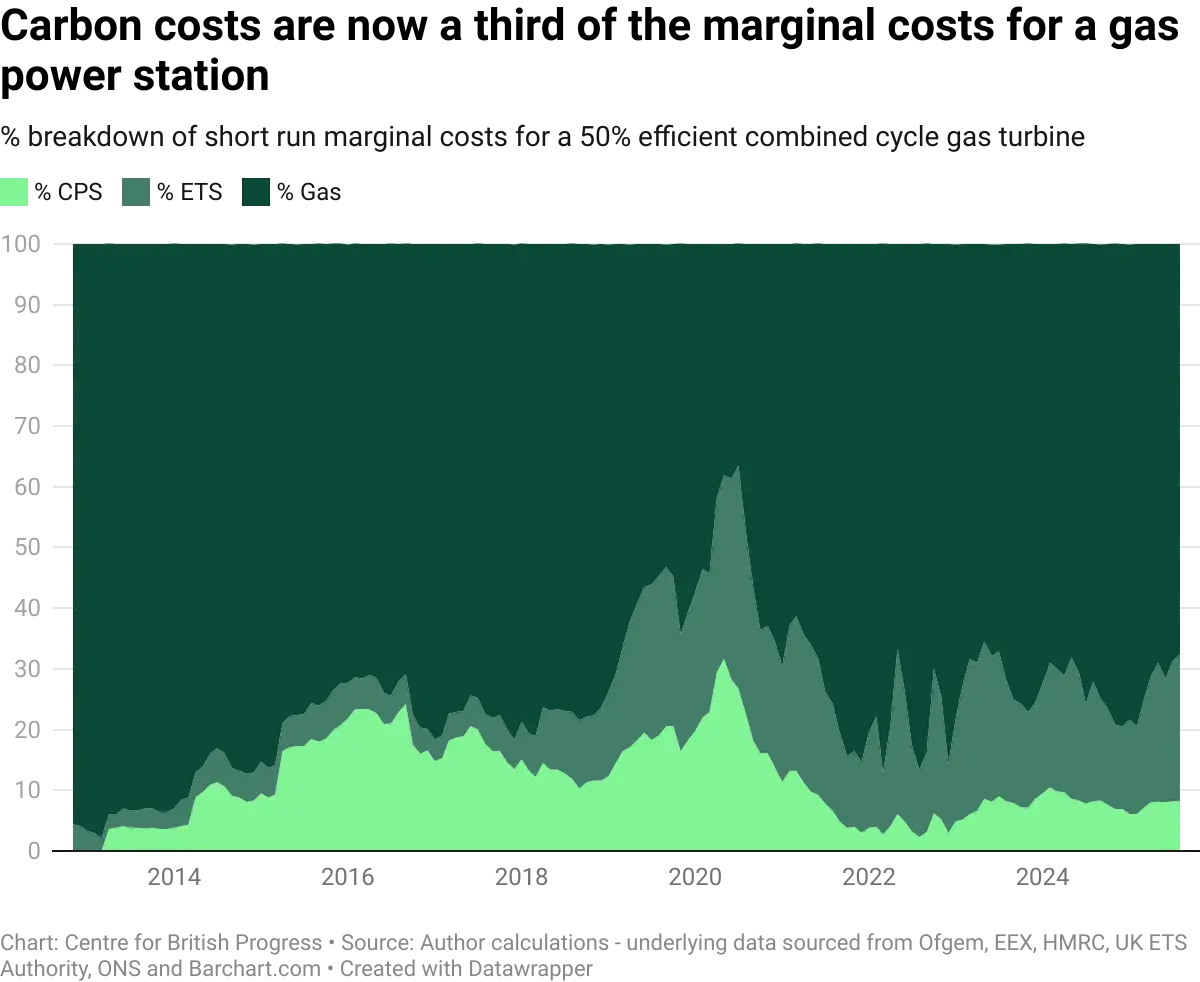

At current gas and carbon prices, carbon costs represent 33% of short run marginal costs. CPS costs make up around 8% of the total.

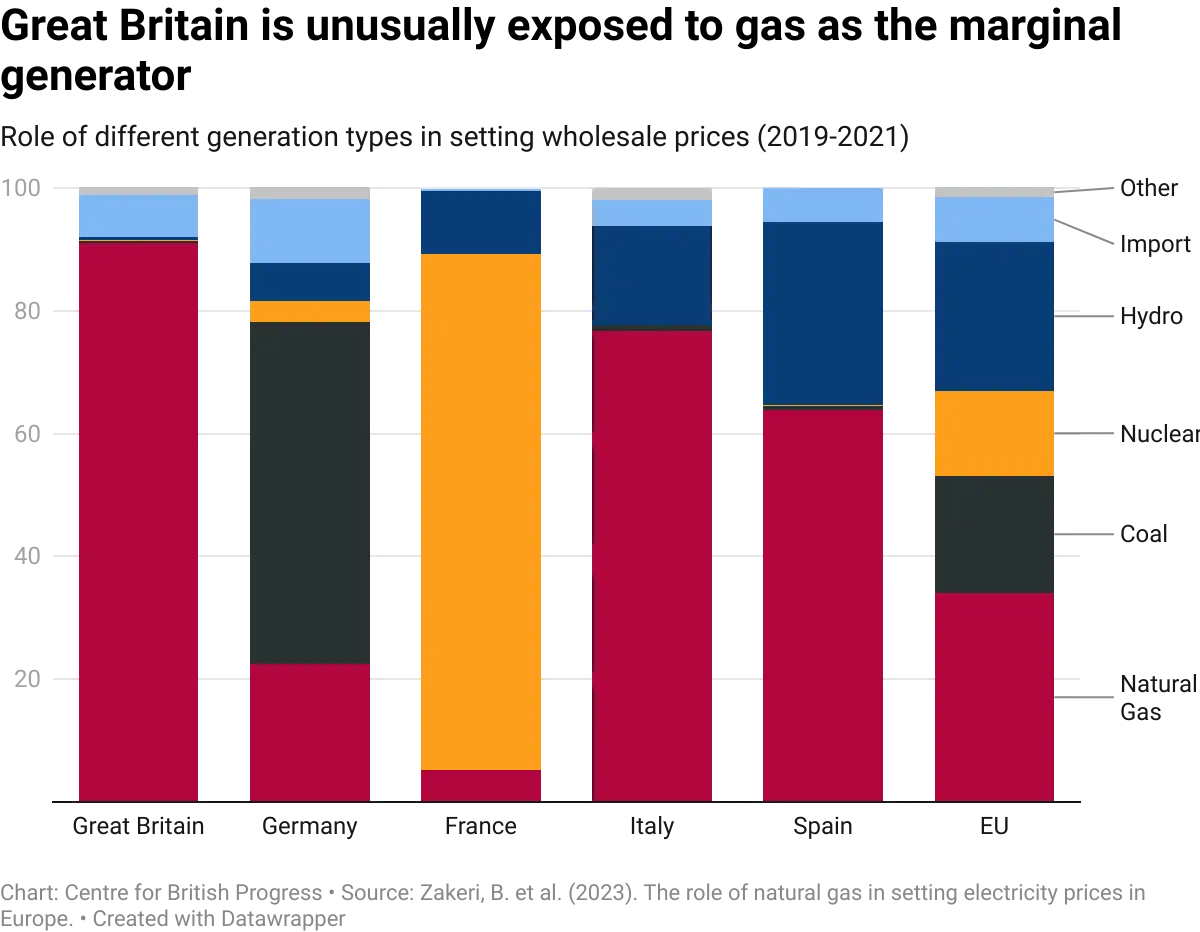

The UK is particularly exposed to this gas generator marginal pricing problem, which drove the massive escalation in UK wholesale electricity prices in 2021 and 2022. Research by Zakeri et al estimates that gas was the marginal price setting technology about 91% of the time from 2019-2021. This degree of single generation type sensitivity is unusual compared to other European countries, which have a more diversified supply of firm generation capacity - particularly in the form of nuclear and hydroelectric power, or in Germany’s case, coal.

Although Britain has made impressive progress in decarbonising its electricity generation, gas remains the country’s backup for the electricity grid. Well into the 2030s, on cloudy, still days, gas will remain the marginal electricity producer.

UK Government policy already recognises that carbon taxes (CPS and UK ETS) drive up electricity costs in the wholesale market. Electricity intensive industries that operate in competitive international markets and are vulnerable to ‘offshoring’ can apply for compensation for the indirect costs of CPS and UK ETS.

Companies operating in 14 different industries, ranging from the ‘manufacture of leather clothes’ to ‘aluminium production’, are eligible for this compensation scheme. The indirect cost is calculated at £25.55 per MWh and is based on the marginal emissions factor associated with fossil fuel generation multiplied by the sum of CPS and UK ETS price. These indirect costs are expected to continue in the “short to medium term”.

Fiscal inefficiency: CPS is a bad tax

CPS is an inefficient tax: it costs consumers significantly more than it raises for the Treasury. Our research indicates that this is getting worse—in 2019 we estimate electricity consumers paid £1.7bn in extra electricity costs, with CPS raising £820m. In 2024 consumers paid £1.6bn whilst the tax raised just £440m. The tax now raises less than 30% of its total financial impact on consumers.

The rest of this cost largely accrues to the owners of legacy renewables (who receive payments under the Renewables Obligation) and to the owners of our existing nuclear fleet. This is because:

- CPS is paid in proportion to the volume of fuel (gas or coal) used by fossil fuel powered electricity generators. Now that coal has closed and gas generation is reducing, tax receipts are falling.

- The cost impact for domestic and industrial consumers is proportional to how often a fossil fuel generator sets the marginal price of electricity in the wholesale market (adjusted for CfD penetration). That is, whenever gas sets the marginal price, all non-CfD generators get paid extra because of CPS.

Improving over time, but not imminently

In the long term, the impact of carbon taxes on the price of electricity, both wholesale and retail, should reduce as:

- Increased deployment of renewables and nuclear will mean gas serves as the marginal generator less of the time.

- Increased deployment of battery storage will act as another source of wholesale market competition, particularly around peak demand periods where today we most rely on gas.

- The proportion of GB generation that is covered by CfDs will rise over time. This will further decouple the link between wholesale and retail electricity prices.

Many of these drivers will take a number of years, and others have direct headwinds. For instance, the UK is currently set to close 4.8 GW of nuclear capacity by March 2030. Further delays at Hinkley C (3.2 GW) would leave the UK with an extended nuclear gap, increasing the price setting influence of natural gas in the medium term. In the meantime, CPS will remain a driver of costs for consumers.

The impact of removing CPS

Removing CPS would save the average household £15 in the fiscal year ending March 2027, a total of around £420m across all households, alongside a further £850m saving for businesses and the public sector. We estimate that this would cost just £400m of lost tax revenue for the Exchequer.

We assumed average household consumption of 3.3 MWh per year, grossed up to c. 3.6 MWh to account for transmission and distribution losses. Savings for a typical (median) household would be around £12 per year in FY26-27, assuming median consumption of 2.7 MWh per year post transmission and distribution losses. Gas power station efficiency is assumed to be 48.9% (GCV basis) as per DUKES 5.10.C in 2024

We estimated the cost savings for an average household if CPS had been removed by estimating the proportion of the time that gas will act as the marginal generator, and the proportion of GB generation that will come from CfDs.

Both of these variables are unknowns. For the proportion of the time that unabated gas sets the wholesale price, we assumed a starting point of 85% in FY24-25 and FY25-26, declining to 16% in FY30-31. 16% is based on the percentage of annual operating hours where gas is expected to be in use under the National Energy System Operator’s Clean Power 2030 New Dispatch scenario.

For the proportion of generation from CfDs, we modelled wind and solar build out based on historic construction times and capacity in line with the lower end of the ‘Clean Power Capacity Range’ within the 2030 Clean Power 2030 Action Plan. Capacity factors assumptions were in line with the AR7 contract allocation framework.

We adjusted for CfD generation within the supply mix because the benefit from lower wholesale prices should be directly offset by higher CfD top up payments.

We assume that the fiscal year ending March 2027 would be the first year of cost savings, based on a November budget announcement and implementation from the 1st of April 2026. In reality it would take longer for anyone on a fixed price tariff to feel the benefit.

Tax system simplification

It is unclear why the UK requires two separate carbon taxes on electricity generators, rather than just making use of the UK ETS. Moving to a single carbon tax would simplify life for both the electricity generation industry and HMRC.

The complexities extend further than just the administrative process of paying and collecting CPS. Another distortion could be removed.

Combined Heat and Power (CHP) refers to the conversion of fuel into electricity whilst also making use of otherwise wasted heat. The UK has a voluntary certification regime called the Combined Heat and Power Quality Assurance Programme (CHPQA) that ensures the quality of CHP schemes in the UK.

Since April 2015, CHP generators that are deemed 'Good Quality' are exempt from CPS with respect to fuel used to generate electricity that is used on-site. Differential tax rates may have made sense ten years ago, when the UK electricity generation mix was substantially more carbon intensive, as onsite generation would have bypassed transmission and distribution losses. It is unclear that this tax advantage should still exist in the context of a much cleaner grid.

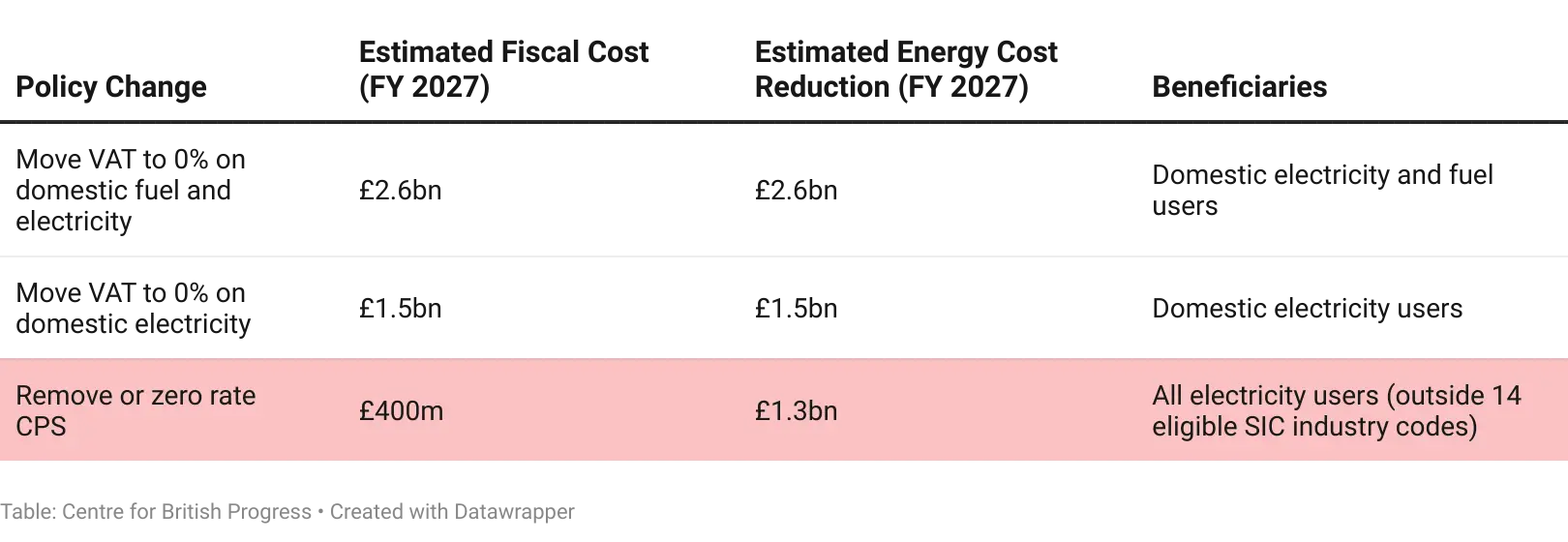

Alternatives to removing CPS

Household electricity bills incorporate a myriad of different policy costs: Renewables Obligation, Feed in Tariffs, Contracts for Difference, Capacity Market, Energy Company Obligation and the Warm Home Discount to name a few.

The Resolution Foundation have also called for the removal of Carbon Price Support as part of a wider package of measures to reduce electricity costs for households.

There is a strong case for moving schemes such as the Warm Home Discount and Energy Company Obligation on to general taxation, as they are more akin to social policy than electricity system costs. Equally, reducing the 5% VAT rate on domestic energy bills to 0% has been covered in the press.

Whilst many of these measures would be welcome, only removing CPS has a ‘multiplier effect’. All of the other options represent a direct transfer - £1 of bill reduction is £1 of extra government spending that would need to be offset by borrowing, taxation or spending cuts.

Whilst removing VAT from domestic electricity bills would focus all of the benefits on households, removing CPS has a much more efficient impact relative to its fiscal cost and spreads the benefits over a broader array of consumers.

If the Government has the fiscal space and is looking to encourage electrification, a combination of removing CPS and reducing the VAT rate on domestic electricity to from 5% to 0% could reduce household electricity bills by c. 6% (c. £65 p.a.) at a fiscal cost of c. £1.9bn in FY27. However, this would be more costly to the Exchequer, and introduce yet another VAT exemption at a time when the Treasury may want to raise broad-based revenue-generators. Removing CPS is a cheaper and less distortive measure which has a disproportionately positive impact on bills for households and businesses.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]