Table of Contents

- 1. Foreword

- 2. Summary

- 3. Why a third runway matters

- 4. What would it take to build a third runway quickly?

- 5. Real constraints

- 6. Part 2: Radical reform to planning infrastructure delivery

- 7. Authors

Foreword

Britain used to build. Our country laid railways, raised cities, and carved out ports that powered the world. We built the first underground trains. We built new towns, bridges, and power stations. All things that made people’s lives better. Today, we struggle to lay a single stretch of tarmac.

The long drift toward this position has been quiet but steady. Well-intentioned rules and regulations were layered on top of each other. Timelines stretched. Permissions multiplied. Infrastructure projects are now a target for challenge, delay, and veto, not just for those who stand to lose out, but for those with no stake at all. We now have a system where doing nothing is safer than doing something, and where process has eclipsed purpose.

This is not sustainable. It is not fair. And it is not how you rebuild a country.

Heathrow is one case, perhaps the clearest case, of this problem in action. A growing economy needs growing infrastructure. More flights departing from and arriving at our biggest airport are good for our economy and a good thing for working people. Even those opposed to Heathrow expansion should reckon with the choice before us. Years of dithering and delay, or a decisive choice made as quickly as possible. It is only the latter which gives people certainty and clarity.

But this isn’t just about aviation. It’s about whether the British state can still make decisions and carry them through.

We all pay the price when the state avoids hard calls. In high rents, slow commutes, unaffordable energy, and missed opportunities. Communities see wealth, growth, and jobs lost, not in theory, but in practice, because projects that could change this country for the better never make it off a page.

We’ve created a system where getting approval for a mile of track or tarmac could take over half a decade. Where ambition shrinks to fit the size of the bureaucracy. And where previous Conservative governments seemed unable to say: “this is in the national interest and we’re going to make it happen.”

We must keep working to change this. A stronger, more confident state is not about centralisation or command and control. It is about leadership. It is about grip. It is about a government that sees its job as delivery, and one that earns back the belief that things can be better, because it proves it.

The report that follows offers one concrete example of how the state could act differently. It makes the case for cutting through delay, changing the process, and making a clear decision. You don’t have to agree with every detail to see the broader point: we must build more, and we must do it faster. And crucially, we can. Not recklessly. Not carelessly. But with urgency, confidence, and purpose.

There is a moral case for building. A fairer economy, with better jobs and more secure lives, depends on it. And in the face of growing global challenges, from energy security to climate change, we cannot afford to keep saying “no” by default. The cost of inaction is already being paid.

We need a politics that can choose. A state that can deliver. A government that does what it says.

If we want a future that works for everyday people, we have to build it. Literally. That starts by fixing the system that stops us.

- Dan Tomlinson

MP for Chipping Barnet and Labour Growth Mission Champion

Summary

A runway is a several kilometre length of reinforced pavement. Building Heathrow’s first runway took around a year. It is everything else that now takes time.

This paper tries to answer a simple question: could the government speed the construction of Heathrow’s third runway to such an extent that flights take off before the next election?

This is not just about building a third runway. The Public Bill and special development order mechanisms we outline here could give ‘decision in principle’ consent to an array of infrastructure projects, with environmental offsets and consultation settled afterwards by the relevant ministers and departments. Parliament could confer this conditional, fast-track consent on entire classes of nationally significant infrastructure - electricity transmission, floating offshore wind, reservoirs, rail - dramatically speeding up the building process.

Labour’s cost of living strategy starts with some basic truths. More clean energy means cheaper bills. New transport links mean more people can get to higher paying jobs. More houses means fewer people sleeping rough on the streets. More airport capacity means cheaper holidays. Reducing the cost of essentials and the cost of luxuries; that is what the British public have been instructing politicians to do since 2022. We have to rip out the process that delays their ambitions.

This paper demonstrates that this approach is feasible for a third runway, if three constraints are tackled head on:

1. Regulatory drag and risk aversion. The Development Consent Order (DCO) process can take six years or more, with billions in investment turning on single veto points, making it rational for developers to spend enormous amounts of time mitigating every potential risk ex ante. A bespoke Heathrow Expansion Public Bill can compress the process for all consents into a single Parliamentary instrument and effectively eliminate the legal risk of judicial review, replacing it with a politically accountable process.

2. Political time-tabling. Using the Public Bill route, programmed for seven months, could deliver Royal Assent by early 2026. If ministers are prepared to override Standing Orders as the government did with Scunthorpe steelworks, the Bill could be enacted even faster.

3. Construction challenges with a long runway. Relocating the M25 makes a long runway nearly impossible within one Parliament. A short-haul runway (for domestic and European destinations) is feasible without moving the M25 and would free long-haul capacity on the main runways.

The strongest constraints on building a third runway are the regulatory process and the construction challenge of moving junction 15 on the M25 without seriously disrupting London’s traffic flows. We believe both of these can be addressed.

Building a third runway by the next election would be a significant and tangible achievement for this Government. It would demonstrate that Britain can build things, at scale and efficiently, in a way that delivers for ordinary families. Perhaps most importantly at a time when the global economy is increasingly closed, hostile and stagnant, this and other schemes like it will spark economic growth and confidence in Britain.

Why a third runway matters

Building a third runway within this Parliament is a worthy challenge for this government. There are strong economic and political reasons to prioritise it.

1. Economic confidence and fiscal headroom: beating expectations on a high profile infrastructure project like the third runway would send a powerful signal that the UK has dealt with one of its major structural economic problems. This will spur investor confidence in the UK, with immediate benefits for OBR and Bank of England forecasts, and therefore the government’s fiscal headroom ahead of the next election.

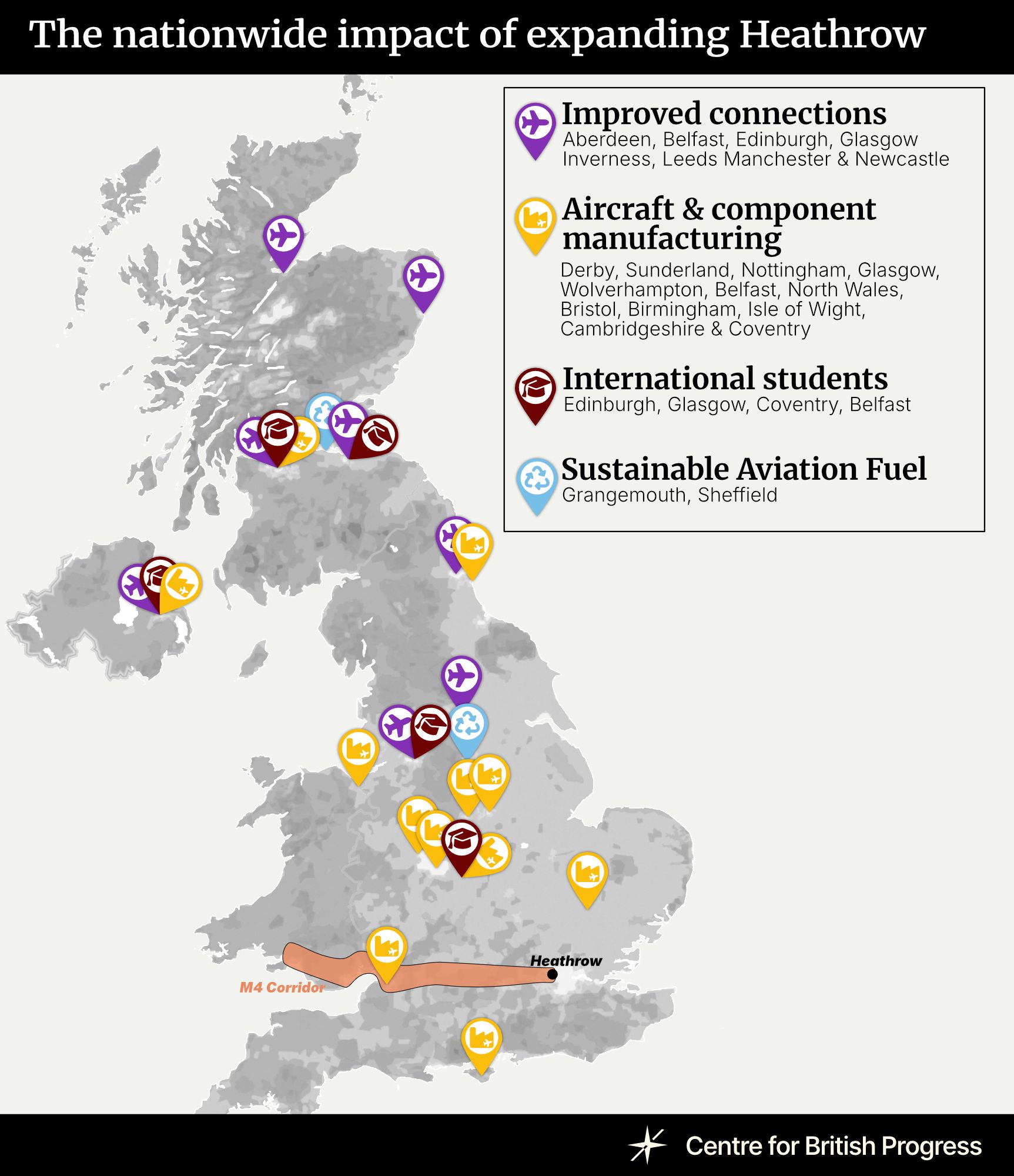

2. Nationwide growth and cost of living: all economic studies point to a positive impact from Heathrow expansion. Expansion (with a full length runway) would reduce air fares by £160 for an average family of four flying on holiday, increase tax revenues and business activity. We expect this to be similar for a shorter runway, as short haul flights could be diverted to this runway.

3. Planning reform: the government has rightly put planning reform at the centre of its growth strategy. Building a third runway offers proof of concept: it is an opportunity to test and reform Britain’s planning system to ensure it works for large national projects. While the mechanisms will be different, the approach we propose for Heathrow could be a template that this government could consider for (e.g.) the Ten-Year Infrastructure Plan, the Ox-Cam Arc and mass transit schemes such as the West Yorkshire Tram. Ideally, Parliament would give certainty on a pipeline of projects, fixing their scope and budgets over multiple financial years.

4. Leveraging central power to drive delivery: the government must demonstrate its political willingness to drive delivery. Projects like Heathrow are inherently political: they require politicians to make big decisions about priorities and trade-offs. We propose that the government grasp the levers at its disposal to compel delivery, and in particular, take advantage of Parliamentary sovereignty to reduce the likelihood of challenge further down the line.

5. Symbolism: Successive governments have failed to deliver a third runway for two decades. Breaking that doom loop would be an emblem that this is the government that got Britain unstuck by building again.

Monetised impacts under the DfT17 central, carbon traded forecasts and revised methodologies (present value, £bn, 2014 prices)

LHR Northwest runway | |

|---|---|

Passenger benefits | 67.6 |

Government revenue | 3.5 |

Wider economic impacts | 1.8 to 3.1 |

Total benefits to passengers and the economy | 72.8 to 74.2 |

Environmental disbenefits | -1.9 |

Airline profit loss | -55.0 |

Net social benefit | 15.8 to 17.2 |

Source: Data from the Airport Commission

Heathrow’s third runway is expected to generate between £15.8 and £17.2bn in net social benefit by reducing prices for consumers and businesses through increased capacity, with passenger welfare gains and reduced business costs substantially outweighing airline profit losses and prospective environmental damage.

Analysis by the Department for Transport projected that the expansion will create £67.6bn in passenger benefits as additional runway slots force airlines to compete more aggressively, cutting fares by an average of £160 for a family of four. More capacity also enables airlines to offer frequent departures and reduce delays that cost passengers time and money. Businesses are thought to gain between £1.8 to £3.1bn from lower input costs as improved freight connections and easier business travel reduce operational expenses. Finally, the government is expected to capture £3.5bn in additional tax revenue from increased economic activity driven by higher passenger volumes and business efficiency gains.

These large gains come at a cost to incumbent airlines and impose some environmental costs. Airlines lose £55bn in profits as intensified competition from new runway capacity forces them to slash prices and accept lower margins across their route networks, while it is thought additional carbon emissions and local air pollution from the increased flight operations represent a cost of £1.9bn.

Importantly, this analysis covers only the operational impacts of running more flights from expanded capacity, not the infrastructure investment itself. Construction and surface access costs are excluded because they represent one-off capital expenditure that creates jobs and transport improvements regardless of how many flights ultimately use the runway. The analysis also excludes agglomeration benefits and congestion costs, which are the productivity gains generated when better airport connections help businesses collaborate and access markets and the costs of greater use of limited public resources, respectively; these benefits could add billions more and can be precisely quantified, but congestion costs remain difficult to estimate.

The results show that operating additional flights from expanded Heathrow capacity creates substantial net economic value for society. Lower costs for passengers and businesses outweigh the combination of reduced airline profitability and environmental costs, justifying runway utilisation even before accounting for broader productivity spillovers from enhanced connectivity.

What would it take to build a third runway quickly?

Istanbul built and started operating an airport with a 1.4 million m2 terminal (four times the size of Heathrow’s Terminal 5), and two runways in just over four years. Beijing built a second international airport with four runways in less than five, with each runway taking around 18 months. A third runway at Incheon International Airport took around 30 months. The longest runway in the US, at Denver International, took under 2 years.

The most significant thing the Government could do to speed up the delivery of a new runway would be to grant permission as quickly as possible. This means overriding the regulatory sediment in the current Development Consent Order process. This can be done through bringing a Heathrow Expansion Public Bill, which would:

- Give a flexible and specific statutory basis for the expansion. This makes the grounds for judicial review extremely limited, because Parliament has made its will clear. It can specify the basis on which subsequent decisions can be made, extending this protection from judicial review to secondary decision-making.

- Serve as a one-stop consenting shop. Rather than navigating the National Policy Statement, DCO regime, EIAs, dozens of secondary licenses and consents from other regulators and judicial review, all consents for the project can be compressed into one regime.

The DCO process could take up to six years, though this government’s reforms should hasten this substantially. Our legislative options paper suggests ways that this could be reduced, but opportunities to judicially review the decisions inevitably add unpredictability and uncertainty. By way of comparison, Sizewell C’s application process took over eight years.

In contrast, we estimate that a Public Bill would take around eight months with a six month post-Bill process. This means that work could begin in 2026.

It is within the government’s gift to go even faster if it is willing to be creative with the legislative tools at its disposal. As demonstrated by emergency efforts to save Scunthorpe steelworks, legislation can be passed in a single day when Parliament decides to do it. Our legislative option section sets out these routes in more detail.

Real constraints

There are six main constraints to the approach which we outline here:

1. Designation as a Public Bill. Infrastructure Bills passed through Parliament are usually deemed Hybrid Bills, which allow an often lengthy petitioning process. Authorising Phase One of HS2 was taken through as a hybrid bill and took 4 years to pass. This is partly avoidable with a strong committee operation, but in our view involves too much risk of delay, hence the preference for a Public Bill.

There is precedent for considering Heathrow expansion a Public Bill. Historically, projects covering London were often found to be Public because of the sheer number of people they affect. It is impractical to hear petitions from millions of people who are affected by Heathrow expansion. There is therefore precedent for treating these Bills publicly.

2. Adverse amendment in the House of Lords. The ideal Bill would be specified with outline plans and allow for secondary consenting and detailed consideration directly by Ministers. Parliamentary discipline would carry this through the Commons, but may face amending pressures in the Lords. Ultimately, this can be resolved through the Parliament Act 1911 but, by constitutional convention, clarity that this is the will of the House of Commons should be sufficient.

3. Necessary regulatory barriers. Our current regulatory system prevents political judgement on priorities and trade-offs. One problem this Bill solves is that if the government wants to prioritise growth over other objectives like minimising noise pollution, it has no mechanism to do so.

Some regulations are not like this. Airspace rules will need to be updated to avoid catastrophic accidents. Some form of assessment will need to inform an Environmental Statement. The government has already committed to ensuring that expansion does not breach our Carbon Budget limits. However, many of these challenges can be considered concurrently and adaptively. For example, in the Luton decision an environmentally managed growth approach was endorsed, which allows thresholds to be set for factors like noise pollution where expansion cannot occur if those thresholds are breached.

4. The politics of expansion. Opponents of Heathrow don’t want it to be built full stop. There will be complaints about overriding existing processes. There are two responses to this.

One is that the existing processes have been poisonous to political progress or settlement. They have engaged proponents and opponents in a decades-long running battle. We should settle the debate democratically through Parliament. One of politicians’ main jobs is to resolve the thorniest issues we face.

A second is that to govern is to choose. Labour were elected on and have chosen growth because they believe it is the only realistic way of improving living standards. They are right about this. That will often mean prioritising growth over other things.

Source: BBC (2025)

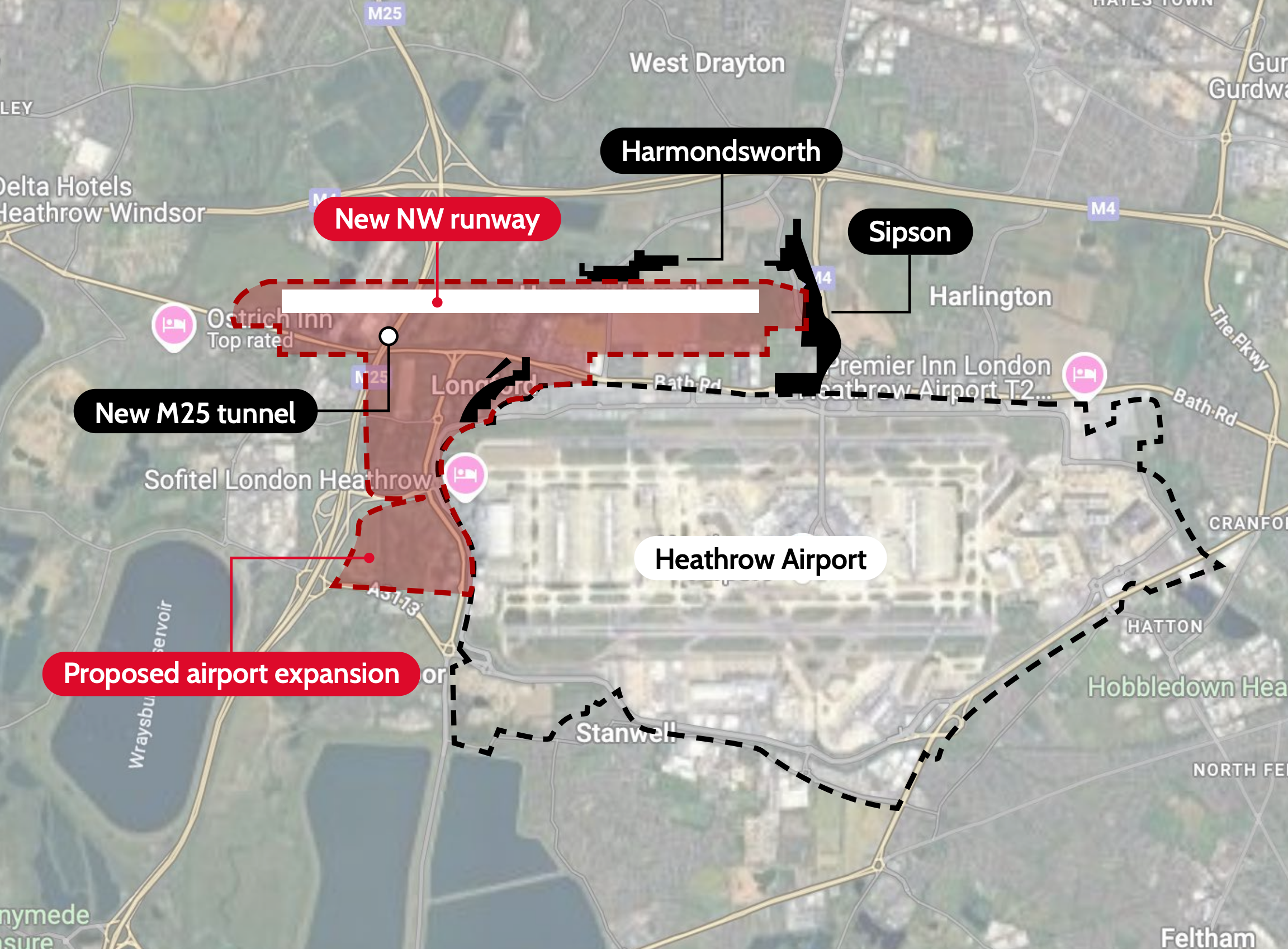

5. The M25 is hard to move. Heathrow’s expansion is physically constrained by the proximity of London’s major ring road to its west and the densely populated areas to its east. A full third runway requires moving the M25 (other options were considered by the Davies review, but discarded because they involve demolishing thousands of homes in Harlington).

This is a major constraining factor in building a third runway within a Parliamentary term, because it cannot be done concurrently alongside the runway extension. It is not necessarily impossible. However, a short runway (which has been considered by Heathrow) is plausible to build without moving the M25.

This means a smaller capacity increase because it would only be suitable for smaller planes on short haul flights. However, it would create longer haul capacity by being the main runway for short haul flights, freeing up capacity on the two main standard-length runways. The government may prefer a deliverable, shorter runway to a more uncertain longer runway. The government could explore the consenting of a short runway with consent to expand it to standard length.

6. Speedy delivery is expensive. Delivery in a shorter period increases the cost of capital that Heathrow will pay to finance the expansion. Construction orders will be more expensive if there is a premium on time. It may not be deliverable using the existing RAB model. Speeding up delivery, of course, brings the economic benefit forward as well.

There is an excellent case for considering alternative financing options, in any case. Airlines are concerned that the current model results in uncompetitive ongoing charges. On the other hand, the slot allocation model, whereby airlines are given take-off slots according to their existing market share for zero cost, is highly economically inefficient and concentrates too much economic value from expansion on incumbents. Selling slots should be considered as one of the main mechanisms for funding Heathrow expansion.

Part 2: Radical reform to planning infrastructure delivery

This section sets out a series of reforms the purpose of which would be to seek to facilitate rapid aviation infrastructure delivery within this Parliament, using the proposed Heathrow Expansion as a case study. This note does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon on that basis.

The current planning regime

The current planning regime applicable to large-scale airport expansion proposals requires an application to be made to the Planning Inspectorate for a Development Consent Order (DCO) under the Planning Act 2008. The decision to approve or refuse consent for a DCO is a matter for the relevant Secretary of State, a decision which is informed by a recommendation report made to the Secretary of State by an independent Examining Authority.

Timescales

Typically, to secure a consented DCO can take anywhere from 2.5 to 6 years inclusive of the pre-application period, during which public consultation and extensive environmental surveys and assessment need to be undertaken. By way of example, the period comprising pre-application consultation to application submission, to decision took well over 8 years for Sizewell C. Using the current regime is therefore likely to entail significant pre-application consultation requirements, and onerous environmental assessment. These issues have been documented extensively and so this paper does not rehearse them, but these requirements do present substantial delivery challenges. Key drivers for the protracted timescales are:

• Need for at least one round of statutory consultation which must also include consultation on a “Preliminary Environmental Information Report.” The government has gone a significant way towards addressing the need to undertake statutory consultation multiple times, but could go much further still (see below).

• Need for extensive environmental assessments which, in and of themselves, are used by objectors to identify potential avenues for judicial review. The wider institutional framework has fostered a culture of risk aversion and of assessment and inclusion of matters in environmental reporting on an excessively precautionary basis, resulting in delays and higher costs.

Policy position

Under the DCO regime, the primary planning policy document against which expansion projects fall to be considered is the Airports National Policy Statement (ANPS). The ANPS sets out that it has effect in relation to “schemes at Heathrow Airport that include a runway of at least 3,500m in length and that are capable of delivering additional capacity of at least 260,000 air transport movements per annum”. There is, therefore, an immediate issue that the existing ANPS may not apply to proposals which are phased to (1) be less than 260,000 ATM and (2) do not involve a new runway of at least 3.5km.

This is potentially a significant issue given that, where a National Policy Statement does not have “effect,” other local and national policies must also be considered and, in all probability, the “need” for the development will be scrutinised to a greater extent.

Judicial review

DCO projects are often the subject of judicial reviews. Most of these challenges fail, but because developers typically do not wish to proceed at risk against the backdrop of legal challenge, given the significant financial and reputational issues at play, projects are often left in limbo whilst the courts determine a challenge (and the appeals which may follow thereafter). The government has confirmed it is proceeding with proposals to limit the number of opportunities for challenge, but it is unlikely that this will fundamentally reduce the potential delay caused by these legal challenges where they are brought before the courts.

Routes to delivery: options

Considering the issues identified above, the current regime could not realistically be used to deliver expansion proposals within this Parliament. We suggest three potential routes below, all of which require significant political will and fundamental reform to the existing process:

- Route 1: Significant reforms to DCO regime.

- Route 2: A Public or Hybrid Bill.

- Route 3: A Special Development Order (likely to enable a more limited form of expansion)

The reforms required for each of these routes are set out in the subsequent sections of this note. The table below summarises the respective advantages and disadvantages of the routes as they currently stand. The timescales referred to in column 1 refer to the timescales assuming the reforms below are implemented.

Route | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

Development Consent Order(≈ 2.5 years, following reforms) | 1. High level of flexibility (but not as flexible as a Public Bill). Level of detail can be in outline and later amended during the consenting stage, with details settled post-consent. 2. Government decision-making reduces risk to developer from objecting local authorities. 3. Lower legal-risk profile than local planning applications (but see Disadvantages 1 & 7). 4. Enables compulsory acquisition of land and amendment of existing compensation rules. | 1. Only applies to expansions > 10 million passengers p.a. 2. Scale of associated development is limited by government guidance (though energy, business/commercial and related transport infrastructure can be included). 3. Protracted timings – likely > 3 years (without reform). 4. Statutory-consultation requirements and mandatory application documents add complexity. 5. Likely need for significant highways and public-transport works/commitments. 6. Must align with any relevant National Policy Statement, which imposes onerous environmental and surface-access requirements. 7. Higher risk of legal challenge than a Public Bill. |

Public Bill setting out a streamlined expansion process(≈ 8 months for Bill + 6 months post-Act) | 1. Very flexible – can legislate in any bespoke manner; detail can be in outline and amended during consenting with details settled post-consent. 2. Legal-challenge opportunities are extremely limited (Parliamentary-proceedings privilege). 3. With mitigation measures, overall timescale could be shortened substantially. 4. Unlimited scope: genuine “one-stop shop” for land acquisition, environmental consents, listed-building consent, etc. 5. Enables compulsory acquisition and amendment of compensation rules. 6. Gives Government high control over permission terms. 7. Could create a powerful, conditional blanket consent for certain site classes, subject to no local-authority/SoS objection within a defined notice period (e.g. six months). | 1. Later detail could be challenged when decisions are made. 2. Risk of being classed as a Hybrid Bill. 3. Adverse amendments in the House of Lords (mitigated by refusing amendments and using HMG majority). 4. Although the Bill itself is immune, post-Act steps remain challenge-prone unless judicial-review reforms (Option 1) are replicated. |

Special Development Order(Limited expansion; ≈ 8-12 months) | 1. Detail can be in outline and amended during consenting, with details settled post-consent. 2. Gives Government high control over permission terms (subject to Disadvantage 1). | 1. Must conform to existing planning policies, constraining what can be consented. 2. Greater legal-challenge risk than a Public Bill; also distinct pre-determination risk if the decision appears fait accompli. 3. Cannot be used for expansions > 10 million passengers p.a. under current rules. 4. Does not allow compulsory acquisition or amendment of compensation rules. |

1. Issue immediate Written Ministerial Statement which states that Government policy supports expansion. This should incorporate a stronger form of the “Critical National Priority” status which is given to low-carbon technology in the energy National Policy Statement (i.e., that there is a critical, and overriding need for the expansion, even where adverse impacts arise).

2. As far as environmental assessments are concerned, the Government should:

a. Use primary legislation to place environmental contributions at the heart of the planning system, whereby a developer agrees to pay into an environmental enhancement and protection fund. This would replace the existing burdensome approach which places undue emphasis on environmental assessment to the expense of an outcomes-focussed approach.

b. Use primary legislation to remove the requirement for Strategic Environmental Assessments for National Policy Statements (and secondary legislation) – as it stands, there is a “double” assessment requirement (i.e., a plan needs an SEA, and a project needs an EIA).

c. Use primary legislation to reverse the effect of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Finch (which leads to excessive requirements for assessment of climate change, and effectively “double counts” the effect of carbon emissions).

3. Introduce an amendment which would enable community benefit payments to be made as part of planning permissions. As it stands, it is unlawful to make payments to local communities for impacts associated with a project as part of a condition in a planning permission which is not related to planning. This rule could be reversed so that payments to locals are expressly endorsed and permitted.

4. Judicial review reforms would need to go further:

- Legislation to make it a ‘one bite of the cherry’ regime. This has been endorsed by the Government in general terms, but of the options shortlisted, the more ambitious legislative option which removes the ability for a challenge to be heard multiple times in the High Court should be adopted. In addition, the requirement for a case management hearing should be removed in the interests of expediting the process.

- Increased caps on the costs that losing litigants can be required to pay (either for failing litigants, or where there is a crowdfunded source for the litigation). There is a risk that the Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee (ACCC) will react negatively to this, but there is no enforcement mechanism in place for remedial action to be taken. This would need to be adopted via primary legislation, or an amendment to the Civil Procedure Rules by the Lord Chancellor. It should be noted that the ACCC has long considered the UK in breach of the Convention due to our ‘loser pays’ system of legal costs, which disincentivises litigants with weak cases. There have been no noticeable adverse consequences for the UK arising from that view.

- Requirement for lawyers/barristers to statutorily declare that a case is likely to succeed and does not cover ground previously dismissed where they seek costs protection. There is a repeated issue of claims being re-litigated even where the substance of the matter has been addressed. This step would require primary legislation.

- More radically, removing the ability to challenge a National Policy Statement or a DCO/planning decision based on an interpretation of a National Policy Statement/national policy. This would entail significant opposition but would reduce the scope for legal challenges in a fundamental way.

5. Set up a Government Department to ‘discharge’ conditions so that HS2-esque local authority approvals are not required. In the DCO regime, National Highways has a discharging unit which sits within the DfT that successfully discharges applications for many secondary consents within days, not weeks or months.

Route 1 (DCO application)

The following reforms would be required to make this a feasible route for delivery of expansion within the timescales of this Parliament:

1. Remove requirement for pre-application statutory consultation, and/or remove requirement for Preliminary Environmental Information Report. This would require primary legislation but would substantially reduce the burden on an application during the pre-application phase.

2. Update the National Policy Statement so that it applies more broadly in favour of the desired proposals. This should incorporate a stronger form of the “Critical National Priority” status which is given to low carbon technology in the energy National Policy Statement.

3. Update statutory guidance to specifically set out that:

a. Only one round of consultation is expected but not required by statute, and expressly cite case law that unless something has gone fundamentally wrong, consultation is not a reason for refusing an application to go through to examination.

b. Pre-examination period is presumed to be no longer than 4 months.

c. Amend the Planning Infrastructure Bill to remove the ability for the Planning Inspectorate to delay acceptance by requiring further information.

d. Remove requirements to have issues resolved, and agreements reached with statutory bodies, prior to an application being made.

4. Repeal all forms of consents prescribed for the purposes of section 150 of the Planning Act 2008 so that any decision to disapply a further consent requirement is left to the discretion of the Secretary of State.

Route 2 (Public Bill)

Hybrid Bills, in recent years, have taken a substantial amount of time to progress through Parliament. For example, HS2 Phase 1 took over 4 years. This is fundamentally driven by (1) programming relating to the need for Committee appearances and (2) the fact that the process involves the use of “Petitions” (i.e., objections from members of the public).

In truth, it is better to avoid a Hybrid Bill for those reasons, and a substantial number of amendments would be required to the Standing Orders of Parliament to enable an expedited Hybrid Bill process. This is not something that should be dismissed as an opportunity, however this paper focuses on a Public Bill route.

Would a Bill for the expansion of an airport be a Hybrid Bill?

A determination of whether a Bill is Public or Hybrid is made by the House Authorities. Importantly, “Owing to the large area, the vast population, and the variety of interests concerned, bills which affect the entire metropolis [i.e., London] used, as a rule, to be regarded as measures of public policy rather than of local interest, and were usually introduced and proceeded with throughout as public bills or were dealt with as hybrid bills.” There is mixed treatment of whether a Bill affecting London is always a Public Bill.

The test for whether a Bill is Hybrid is whether it affects some class of people in a distinct manner. To ensure this does not prevent the Bill proceeding as a Public Bill, a ruling from the Speaker re-stating the test of Hybridity should be applied. It could, for example, be limited to ruling out the hybrid route for airport expansions in the Southeast given the substantial number of people affected by the proposals. The Hybridity test that rules out this being considered as a Hybrid Bill. This could be strengthened by the Public Bill being clear that the existing CPO regime under the Acquisition of Land Act 1981 may be utilised in connection with the proposals, clearly giving landowners their compensation rights.

The other option to avoid Hybridity is to make the Bill “general” in how it functions (e.g., it would enable airport expansion anywhere subject to some other approval or consent). This, however, gives rise to its own political constraint. If the “test” on Hybridity is changed, that would provide a more preferable route to utilising this route.

What would the Bill authorise?

What is authorised by the Bill turns on how much information is available, and secondly what level of information Parliament considers necessary. The former is outside the control of the Government, whereas the latter is malleable. On one end of the spectrum, the full design parameters and construction details could be authorised by the Bill. Where this level of information is available, it is usually used to justify fewer controls post-enactment. On the other end, outline details could be authorised. Naturally, this is typically used to justify a greater number of controls and secondary approvals following the Bill being enacted (e.g., HS2 contains an authorisation for an outline set of plans which are then subject to further control).

With Parliamentary will, less detail is possible, but this requires significant party discipline. There is, nonetheless, a risk of adverse amendments in the House of Lords. This too is not insurmountable but would require the Government resisting a number of amendments, and potentially overriding the House of Lords (via the Parliament Act 1911).

How will environmental assessments be carried out?

For Hybrid Bills, there is a requirement to produce an Environmental Impact Assessment. This does not usually apply to Public Bills (on the basis that they are general). Standing Orders would need to be adapted to provide comfort that some form of assessment would be provided in connection with a Bill. However, this could seek to take a light touch approach. It is difficult to challenge the adequacy of an EIA in the context of Parliamentary proceedings on the basis that a court cannot trespass on Parliamentary proceedings.

Overcoming the issues relating to a Public Bill

Issue | Reform/Resolution |

|---|---|

How can the Government promote a scheme in respect of which it does not have the details? | Close co-operation with the airport operator is required. Note, the example of Universal Studios working with Government is a useful starting point. |

Isn’t there an issue of Parliamentary time being available for a Bill? What about adverse amendments from the House of Lords? | Potentially. This is a matter for the Whips Office; they can prioritise passage and the order of business. Though it may seem trite, the various Bills passed in 2–3 days during the Brexit negotiations show how Parliamentary will can overcome usual challenges. |

All the detail cannot be provided quickly – how do we resolve this? | This could be resolved through a system of “environmentally managed growth,” recently endorsed in the Luton Airport decision. In practice, thresholds are set for areas such as noise, carbon, public transport, and air quality; growth cannot proceed where thresholds are breached. This requires adaptive monitoring and mitigation. Establishing thresholds takes time, but reduces objection risk and shows due consideration. As far as further details are required, these could be dealt with as “conditions” or subsequent approvals which are required (see directly below). |

Can subsequent (post-enactment) approvals delay and be challenged? | Yes. Delays can be minimised by avoiding Bill amendments that add excessive secondary approvals and by ensuring a central discharging team (see above). Wider judicial-review reforms would also help minimise JR risks. |

Route 3 (Special Development Order)

As it currently stands, a Special Development Order cannot be granted for a proposal of a scale which is above the DCO thresholds. It would be possible to amend the threshold (using secondary legislation) to enable a wider use of this route. It should be noted that the Government is currently considering the use of an SDO for the Universal Studios theme park proposals in Bedford, and SDOs were used historically for

substantial regeneration, including in connection with New Towns.

There is likely to be significant pushback to:

- Bringing substantial airport expansion outside of the DCO regime so another option here is for the Government to grant an “opt-out” of the DCO regime (something enabled by the Planning Infrastructure Bill), and then utilise this route; and

- Using the SDO route given there are no consultation requirements.

The other limiting factor is that an SDO is made by the Government, and it may not have all the necessary information to ensure, for example, compliance with national policies relating to traffic and wider transport impacts. Even if compliant, there is a further risk that a number of local plans (e.g. the London Plan) would reduce the prospect of a safe consent. Whilst the new national policies (see above) would assist with reducing the scope for legal challenge in that context, it is likely that the greater in scope the expansion, the more likely a successful challenge. It is for this reason that, unless Heathrow can provide evidence of compliance, this route should only be used for a more limited expansion.

Limitations

The above recommendations are subject to further consideration on:

1. Non-regression: we consider the Government needs clear advice on the scope of the level playing field requirements arising from the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, and other international obligations. It could be argued that the systems/processes suggested above do not lead to an overall reduction in environmental outcomes, but strong legal advice is required on this issue.

2. Availability of information: the amount of information about the proposals will help determine the precise route which is the most expeditious. It is not clear exactly how Heathrow proposes to phase its proposals.

3. Slots: we consider there is a useful exercise of instructing lawyers on the process to use slots and other charges to help fund infrastructure development. This is a highly complex issue but could unlock the ability for private financing options to come forward more quickly, thereby enabling construction during the term of this Parliament.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]