Table of Contents

- 1. Foreword

- 2. Toplines

- 3. The need for speed

- 4. Planning reform

- 5. Environmental regulation

- 6. Power

- 7. Authors

Foreword

By Matt Clifford

Britain is the birthplace of the first industrial revolution. It made Britain the richest country in the world and left some of our grandest and most beautiful infrastructure - from town halls to railway stations - as its physical legacy. But we have forgotten how to build, and this amnesia is the root of our economic malaise. We do not build enough housing, transport or energy infrastructure to support good jobs and good lives and to fulfil our national potential.

The next industrial revolution, powered by advances in artificial intelligence (AI), is being built elsewhere. Before the end of the decade, the consequences of Britain’s failure to build could become acute. ‘Who builds wins’ will be the mantra that secures economic and geostrategic advantage in the 21st century. Other countries, from the UAE to France, and of course the United States, are building at scale to secure AI investment and the infrastructure of the future. Unless we act quickly, Britain will fall behind.

This report rightly starts from the position that AI will be transformative and that Britain cannot afford to miss out on it. And we need not miss out: we have the talent, ingenuity and expertise to fully harness AI. But until we fix our restrictive planning system, Britain will be a difficult place to build and scale the AI infrastructure and the AI companies that will drive improvements in our wealth and health.

The Government has understood this challenge. In embracing my AI Opportunities Action Plan, the Government placed AI at the heart of its economic strategy and physical data centres – situated in ‘AI Growth Zones’ (AIGZs) – at the heart of its AI strategy. The recently announced schemes, totalling £30bn in private investment, show that this is the right approach. But without reform, Britain risks delaying or losing these opportunities if vital physical infrastructure gets mired in planning.

This report from the Centre for British Progress is therefore crucial and timely. It outlines the legal and regulatory frameworks that, if adopted, could accelerate AI Growth Zones, and release them from the fate of recent British infrastructure projects – cost overrun, inefficiency and delay. This will require new legislation, such as a new AI bill or critical infrastructure bill, to fast-track all planning-related approvals for AIGZs.

The Government has many options, but the most ambitious, and promising, proposed here is that Britain should learn from Canada, whose Liberal Government recently introduced the Building Canada Act. Once a project is designated as in the national interest, all necessary federal approvals are deemed granted, shifting the debate from ‘whether’ to build to ‘how’, with conditions set by a single minister. The aim is to allow programmes that might take decades to be completed in just two years. The Act streamlines regulatory approval for infrastructure projects that are critical for economic growth, security and autonomy. AI infrastructure, located within sovereign territory, can underpin all three.

We cannot know today exactly how AI will reshape Britain’s economy. However, we do know that Britain cannot afford to be missing in action as this technology develops. Our people deserve a stake in this technology and Britain must have a seat at the table.

AI infrastructure gives us optionality for different AI futures and enables technological sovereignty, which reduces dependence on assets and capabilities outside of our control. Moreover, AI infrastructure has an immediate economic dividend - the trillions of dollars being invested in training and serving new AI models today - as well as huge potential future economic dividend through gains in worker productivity and the creation of new applications and companies.

The first industrial revolution was built in Britain and if we make the right choices, such as those proposed in this report, the next one could be built here too.

Matt Clifford is the chair of the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) and founder of Entrepreneurs First. He was recently the Prime Minister’s AI adviser and authored the AI Opportunities Action Plan.

Toplines

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) will reshape the global economy. The Government is rightly prioritising building AI Growth Zones – based around data centres – to ensure the UK can benefit from this technological revolution.

- However, Britain’s slow planning system and badly-designed regulation threatens to delay or even block AI Growth Zones (AIGZs). As with our failure to build other physical infrastructure, Britain cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the last 50 years.

- The UK has secured the promise of billions of pounds of investment from AI companies and hyperscalers to build data centres. However, delivering on this, and doing so quickly, will require legislation to reform our planning system.

- Mark Carney’s Liberal Government in Canada has successfully passed a new act that will massively accelerate infrastructure approvals. The UK should learn from this and pass a Building Britain Act to enable AI Growth Zones to be approved quickly.

- This builds on our recent recommendations for how a new runway at Heathrow could be delivered using a public bill.

- We also set out a raft of other improvements the Government can make that could speed up planning for AIGZs and other infrastructure including a new delivery authority and reform to judicial review.

- On environmental and habitats regulations, we propose that the Government look to schemes that are effectively delivering growth and a high level of environmental protection in Europe.

- Finally, we set out an energy scheme to help Britain compete internationally for AI investment whilst also making long term contributions towards decarbonising our electricity supply

The need for speed

Britain is in a global race for AI investment. This year the largest AI firms and data centre developers are expected to deploy $375bn in capital expenditure, rising to $1.2tn in 2029. OpenAI has plans for a Stargate facility in Norway, which could reach 520MW, one in the UAE which has a stretch goal of up to 5GW, and that’s not to mention their plans for huge developments in the US. The UAE and France have also signed an agreement to deliver a 1GW data centre in the heart of Europe.

Britain is extremely well placed to benefit from this investment: we have a deep pool of expert AI talent, a mature existing data centre industry and a strong location between Europe and America. Britain’s entry into the global race—with recent investments announced at the recent UK-US summit—is a promising start, but its success will depend on faster delivery than has been possible under the current system.

These investments are all about speed: the huge capital costs of data centres mean that projects are extremely sensitive to delays, which can incur billions in extra spending; and AI labs are all rushing to develop and deploy larger and larger models, they simply cannot wait for slow approvals. OpenAI announced in the last few weeks that two of their Stargate sites will scale to 1.5GW within the next 18 months. xAI’s new Colossus 2 cluster in Memphis has gone ‘from zero to 200MW’ in six months. By comparison, National Highways claim to have run 375 days of active public consultation on the Lower Thames Crossing, a scheme, with the current (second) planning application taking 28 months from submission to decision.

If data centres cannot be built in Britain far more quickly than is possible under current law and policy, they will be built elsewhere. Unless we speed up delivery, projects will go abroad, and we will miss out on the economic growth that the AI revolution offers.

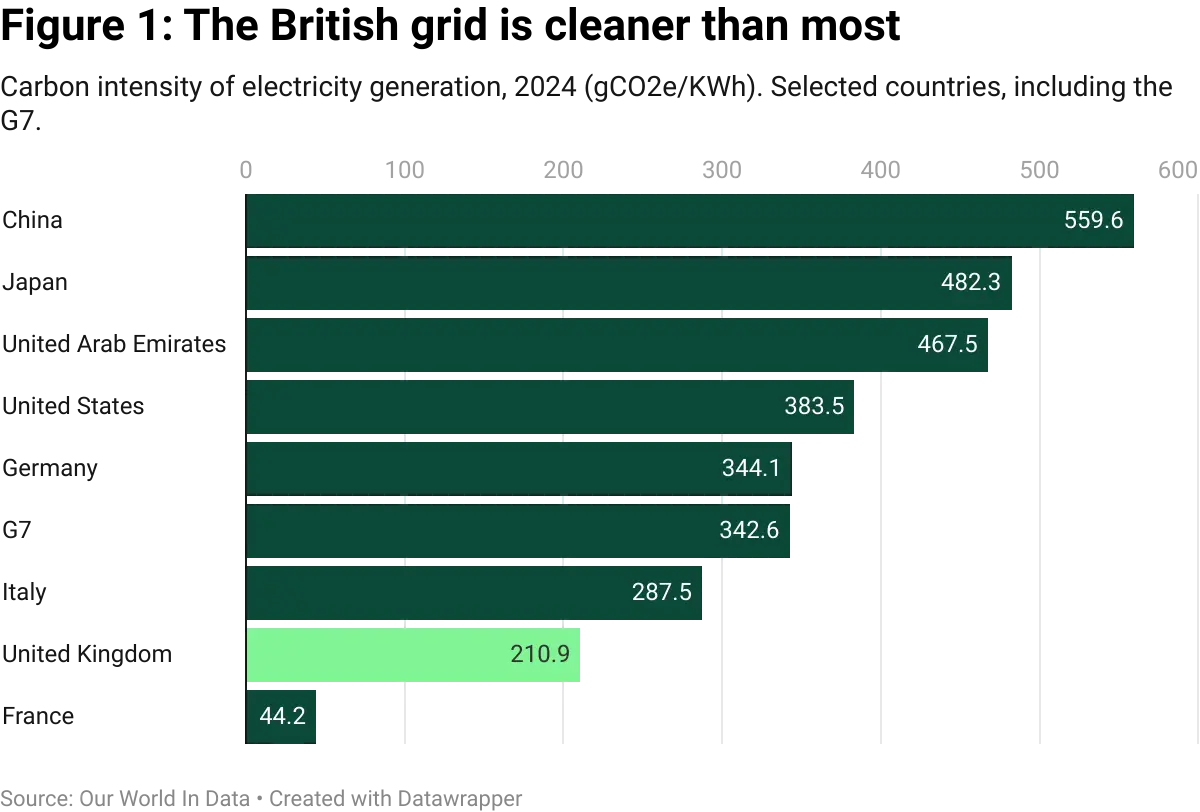

Enabling this investment is not just good for Britain, but good for the world. Britain has, by international standards, a very low carbon grid as well as plans to decarbonise it further. Data centres connected in Britain will be by default better for the environment. From an AI security perspective, it is better for data centres not to be concentrated in the US and China, but for AI capacity to be shared among liberal democracies.

The Government has made great strides on getting the economy ready for AI fueled growth. In this paper we outline how they can unblock AI Growth Zones— which are central to the strategy—and ensure that the deals they have struck and investment they have attracted will not go to waste.

Planning reform

Britain’s difficulty with building infrastructure projects is no secret, and recent experience suggests performance is deteriorating rather than improving. The Development Consent Order for the Lower Thames Crossing took two tries over five years. The proposed A303 tunnel under Stonehenge was under consideration from 2018, with two judicial reviews delaying its progress before its final cancellation in 2024. These delays apply as much to private projects as they do to Government-sponsored ones. Not all of the delays are in planning - environmental and habitats regulations, the threat of judicial review and slow grid connection timelines will all need to be fixed for Britain to compete in the global AI race. But fixing the delay and uncertainty systemic to the British planning system needs to be the Government’s first priority.

The Government correctly sees building data centres in Britain as critical to both economic growth and national security. However, without ambitious improvement this will be jeopardised by our planning system, which now incorporates a legal mess built up by successive governments. Those rules neither deliver on their environmental ambitions, nor on their ambitions to deliver higher welfare for the people of Britain.

Depending on the Prime Minister’s ambition, he has a wide range of options for fixing planning and environmental approvals. Some of the issues faced by projects in the UK can be solved, or at least ameliorated, through changes to secondary legislation and policy. Others will need only small tweaks to primary legislation. But to fundamentally fix Britain’s competitiveness, the Government needs to revolutionise how it approves major projects in the UK.

A Building Britain Act

The most powerful way to unblock AIGZs in the UK would be to pass primary legislation, a Building Britain Act, modelled on the Canadian Liberal Party's successful recent reforms. This would be limited to areas where development will be most socially beneficial, and will have four major advantages:

- Reducing costs and speeding up development by doing a single Strategic Environmental Assessment, rather than individual assessments for each application

- Ensuring overall environmental improvement, not immense sums wasted on litigation and delays

- Encouraging investment with speed and certainty

- Reducing the risk of judicial review and the need to re-decide applications for narrow technical reasons, which creates costs that could instead be spent on environmental improvement and causes delays and uncertainty that lead to jobs and investment going abroad

The cumulative effect of years of statute and case law now forces major projects through multiple, sequential veto points with overlapping mandates. There is no clear place for elected government ministers to plan strategically for the benefit of society and the environment. This means that radical reform will need primary legislation to enable the Government to make decisions again.

This problem is not new. In 2008, the then Labour Government recognised that the existing patchwork of consenting processes, under the Town and Country Planning Act, Transport and Works Act, and others, was unwieldy. They created the Development Consent Order (DCO) and the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP) regimes to approve them.

The DCO was meant to be a ‘one-stop shop’ that rolled planning permission up with all the other consents required for a project. That meant that, for example, the Secretary of State could disapply, say, the requirement for an environmental permit issued by the Environment Agency, instead dealing with those issues all at once. But section 150 of the 2008 Planning Act frustrates that by requiring signoff from the normal regulator, who can delay by months. The time taken to decide an NSIP application has also lengthened since application, with rounds of consultation, process gold-plating to avoid the risk of judicial review (JR) and slow political decision making. DCOs have been getting slower, with the average time for consent rising from 2.6 years in 2012 to 4.2 in 2021.

Later in this paper, we set out ways in which the NSIP process could be reformed and many of these issues ameliorated so that the regime can achieve its original objectives. However, given the opportunity for hundreds of billions of pounds of inward investment that AI potentially offers, combined with the risk of missing the boat on AI and the associated fierce global competition, there is a case for going further and introducing a new, more radical process for a clearly limited set of sites.

This growth offers a profound opportunity to reduce the cost of living for the British people; to invest more in the NHS; to fund and deliver better public transport in our regions. But we will lose that opportunity if we do not grasp it firmly and quickly.

The UK should learn from its fellow centre-left, Commonwealth Government, Mark Carney’s Liberal Party in Canada, and seize the chance to fix planning for this critical infrastructure of the AI revolution.

Following Canada’s example

Faced with the threat of President Donald Trump’s tariffs, recently elected Prime Minister Mark Carney passed the One Canadian Economy Act. Whilst half of the act focuses on liberalising trade restriction between federal provinces, part two, known as the Building Canada Act, allows the Canadian Cabinet to declare an infrastructure project to be in the national interest.

Such projects are subject to a significantly less onerous approval procedure:

- Automatic granting of specified federal regulatory approvals

When a project is added to the national interest schedule, the Minister has the power to issue a single authorisation document, replacing a raft of federal regulatory approvals that would normally need to be granted individually. - Projects have a single point of contact through designated minister and Major Projects Office

Once a project is listed as being in the national interest, it benefits from streamlined coordination through the Major Projects Office, which serves as a single point of contact with various federal departments. A designated minister ultimately issues one binding set of conditions that constitutes authorization under all applicable federal statutes, eliminating the need for multiple separate approvals. - Focus shifts from 'whether' to 'how' to build

The regulatory review process is reframed around implementation rather than fundamental approval. Projects still undergo environmental and other reviews, but these focus on establishing appropriate conditions for proceeding rather than determining whether the project should proceed at all, providing much greater certainty to developers. - Streamlined timeline from five years to two years

The Act aims to compress the typical federal approval process from five years down to a two year target through coordinated reviews and single-point decision-making. - Reduced judicial review risk

The Act significantly reduces the 'attack surface' for legal challenges by collapsing multiple federal approvals into a single ministerial authorisation document. This reduces opportunities for serial litigation that can otherwise delay projects for years. By specifying that neither Cabinet designation orders nor ministerial authorisation documents are statutory instruments, the Act removes common procedural challenge points.

The upshot is that the act will make the process of consenting projects that have political will behind them significantly easier and, crucially, faster. It shows what a centre-left, liberal democracy can do when faced with the challenge of boosting economic growth.

Britain faces a different set of legal constraints that mean that a Building Britain Act could not be copied wholesale from Canada. But the principle of parliamentary sovereignty provides the UK with huge flexibility to streamline approvals, provided the Government is willing to use primary legislation decisively.

Britain remains bound by international obligations that constrain options for reform. The UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement includes non-regression clauses on environmental standards, while the Aarhus Convention limits how far judicial review can be restricted. EU-derived environmental assessment requirements, though now a matter for domestic law, carry significant legal and political weight. These constraints are real, but they are comparable to the constitutional and federal limitations that Canada navigated successfully.

Like Canada, Britain can work within these constraints through smart legislative design. Canada managed to maintain environmental protections and Indigenous consultation while dramatically accelerating timelines. Similarly, a British Act could preserve environmental standards and public participation rights while eliminating duplicative processes, serial litigation opportunities, and bureaucratic coordination failures that add years without improving outcomes.

How a public bill would work

For AI infrastructure, the UK should follow Carney’s example: a new process that blasts through decades of accreted process. The best way to do this within the British legal system is to grant automatic permission for specified types of development within AI Growth Zones (to be designated by the Government), subject to a power for the Secretary of State to block inappropriate projects where needed.

The bill would set out the following process:

- The Government prepares a Strategic Environmental Assessment (‘SEA’) covering the areas it intends to designate as possible AI Growth Zones and the types of development and conditions that it intends to specify within that designation.

- The Secretary of State designates the zones using powers created in the bill. That designation provides for automatic permission, within the zones, for the types and extent of development specified in the designation (i.e. an ambitious zonal permission system), subject to subject to the conditions set out in the designation to ensure overall environmental improvement, and subject to non-objection by the Secretary of State.

We also propose that this power be open to the mayors of city-regions, and potentially to local governments not included within a city-region. These mayors should be empowered to designate zones and prepare the SEA just as the SoS, with the permissions granted being cumulative if both levels of Government designate the same area. Locally designated zones should come with a revenue raising power so that the mayoralty can recover the cost of the SEA and designation from the developers who ultimately build out the AIGZ. This locally-led option would enable development to come forward in areas that are a local priority for regeneration. - Developers can make an application to build AI infrastructure in the zones, and permission is automatically granted after a fixed time period unless the Secretary of State (or relevant mayor in the case of a locally designated zone) objects. The permission under the designation will include the necessary regulatory approvals that would otherwise need to be sought separately—a true one-stop-shop.

Crucially, the bill should:

- Require the zone designations to include bright-line rules for the types of site covered and permitted facilities

The Bill should require the designations should be specific, setting out clear, ‘bright-line’ rules for what is permitted. Leaving room for interpretation by the courts will give rise to judicial review and delay. The Bill should ensure that everyone has complete certainty and clarity regarding eligibility and approval, and that this can be established quickly and easily.

The designations should be clear on what is allowed on the site. This should be a wide and flexible envelope, within which the developer has latitude to optimise their design. The designation will of course need to include further rules, especially for environmental protection. The clearer and broader the rules, the lower the risk of judicial review. We should not seek to predict the future on the specifics of layout, technology choice, etc. The limits should be generous, and vary with clear aspects of the site. For example, the designation might permit buildings of up to a certain height or co-located power generation up to a certain megawattage. - Replace performative environment-related processes with clear substantive environmental improvement

Britain has some of the highest environmental standards in the world, as well as a rapidly decarbonising grid. This makes it one of the greenest places in the world to build new AI infrastructure. Our rules governing environmental review have, however, become too cumbersome and process driven, losing sight of the core goal of ensuring development can only improve the environment. The Government should make a number of tweaks to these regimes that would be a win-win for growth and nature, which we set out below.

For AI Growth Zones specifically, Britain will need to go further to ensure that data centres that meet the necessary environmental standards can be brought forward quickly. The bill should give the Secretary of State and city-region mayor each the power to complete a Strategic Environmental Assessment for all or some of the AIGZs at once, and for this to replace the requirement for EIA for every project within the zones if that project was covered by the SEA. As in Germany, the bill will need to provide for the applicant to apply to SoS, the city-region mayor or (in other areas) local government to confirm that the project does not give rise to significant effects not foreseen by the SEA, with a statutory presumption that there are none. This approach is justified by the narrow range of sites that will be covered by the zones, by the exclusion of any environmentally sensitive land, and by the provision of funding for nature enhancement. In this, the UK would be following the approach of the EU’s latest Renewable Energy Directive, which adopted Germany’s approach.

The SEA would identify any features of the zones that would experience ‘likely significant effects’ from its development and would set out the high standards, clear rules and exclusions that the Government’s later designation will impose on any development in the zone. This will allow the SEA to assume a broad envelope of development so that it can cover and address any possible environmental impact up front, without reducing flexibility for projects. The SEA would help determine an Environmental Improvement Levy that developers would pay, set at a rate that ensures overall environmental benefit. Developers within the zone who meet the required standards would then not be required to complete bespoke environmental assessments. We set this idea out in more detail below.

Such plan-level assessments are already standard practice across Europe. The European Union created an explicit route for member states to designate 'acceleration areas' for renewable energy: zones assessed once at plan level where compliant projects are fast-tracked and, in many cases, spared individual EIAs because an umbrella assessment has been performed. Germany, France, Spain, and Denmark have all implemented versions of this. Most of these countries also have pooled, or national, mitigation schemes to ensure that development delivers environmental improvement, as we suggest below.

Only primary legislation like this proposed bill can allow the Government to follow the German, Spanish and other EU practice of doing a single SEA that replaces the need for individual EIAs for each project within AIGZs. The legislation would deem that the presence of the SEA disapplies the requirements for EIAs for subsequent development within the zones. This will accelerate the process and reduce costs. Without primary legislation, the power does not exist. - Enable a template Environmental Delivery Plan

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill gives Natural England the power to create Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs), area-based plans that combine mitigations and a levy to handle habitats and protected-species issues strategically. The Bill should direct Natural England to create a common template for AIGZ EDPs, and that Natural England should create an EDP for each AIGZ on designation, with a strict deadline. Where a project is within the EDP’s scope and the levy is committed, specified Habitats Regulations/protected-species effects are treated as addressed. This complements the SEA approach to environmental assessment. - Provide for local benefits

The bill should seek to retain the goal of the current planning system to ensure that new construction also benefits local residents. The bill should provide that zone designation can include conditions for payment of funds that the local authority can spend, for example on a new doctor’s surgery or school building.

An ambitious bill like this has significant advantages:

- Speed and certainty

The bill would create a standing, rules-based route with a hard statutory clock: consent is deemed unless the Secretary of State objects within a fixed window. Unlike a Development Consent Order, the timelines would be shorter and more streamlined, and avoid pre-application and examination procedures which take significant time. This would also contrast with the Local Development Order (LDO) route which takes too long to compete globally for AI investment. The Ratcliffe-on-Soar industrial park took 19 months whilst the Didcot Technology Park LDO took well over two years for initial approval. Even once approved, these conventional planning routes often require a large number of expensive, slow and crucially uncertain other approvals.

Unlike the Special Development Order, LDO or conventional route, this new regime should be capable of approving co-located power generation above 50MW. Currently this is only possible through a full DCO.

Another alternative would be for SoS simply to call in applications. However, this does not give investors sufficient confidence to invest large sums in developing a full application, given that the relevant ministers may change before the application is decided. The existing routes simply do not respond to the demand, and need, for speed and certainty. - Limited scope encourages appropriate development

This bill would not grant the Secretary of State power to designate every location across the country: the areas of immediate application should be limited to certain classes of brownfield land such as former industrial sites, quarries and ports. This could be supplemented with a power for the Secretary of State to designate additional areas, subject to parliamentary approval. By limiting the bill's scope, development would naturally be directed towards the most environmentally appropriate sites. - Reduced JR risk

While the bill (once an act) itself would be primary legislation and therefore not subject to judicial review, the courts would be able to review the process for deciding whether to reject applications. The bill should include a strong statutory presumption in favour of development, which would make a court less likely to strike down any decision. This, combined with the reduced number of separate consents needed, and the JR reforms we propose below, would result in a process significantly more robust to challenge than a DCO, LDO, SDO or call-in. The courts will also be less likely to compel a minister to do something (i.e. to object to a development) than they would be to quash an active decision. - Avoidance of hybrid bill procedure

Another option to leverage the power of Parliament to approve AI Growth Zones would be to use a hybrid (or private) bill. Traditionally, large, privately promoted construction schemes in Britain were approved by Parliament as private bills, with an ad-hoc committee of MPs tasked with considering petitions from those who would be affected. HS2, which went through as a hybrid bill, demonstrated how, today, this procedure is slow and unwieldy. For the first HS2 Bill, the committee received over 2,500 petitions, 1,600 of which were heard in person, taking years. Whilst an AI Growth Zone is unlikely to affect as many people as HS2, designing a consenting route that is passed as a public bill will avoid these issues. - Smaller fixes

Many of the other fixes and improvements we have set out in this paper require primary legislation. The Building Britain Act should also include other powers that can be in force straight away, speeding up smaller projects before full implementation. We set out many of these below. - Industrial strategy

Our proposed bill would allow the state to play a key role in driving our industrial strategy to deliver prosperity, regional growth and wider social outcomes. This is because it solves a key coordination problem: many AIGZs will have multiple developers, each of whom will have different financing and development programmes (e.g., an electricity developer may be able to move more quickly than a hyperscaler).

The existing routes, including DCOs and LDOs, are not well-structured to deal with this scenario, with no single delivery authority likely to take on the burden of financing the planning application for the zone as a whole. In addition, there is a specific environmental assessment risk for these zones under existing regimes whereby the absence of information for different developments may pose a risk in each, particularly the first, application.

The new bill would de-risk this scenario: the Government would be empowered to plan across multiple AIGZs at once, making sure that Britain’s AI infrastructure aligns with our industrial strategy and meets the country’s needs, all while leveraging private capital to boost economic growth.

Beyond AI Growth Zones

An act like this could be expanded to have applications for infrastructure well beyond data centres and AI Growth Zones. In our recent paper with Labour Together, we proposed such a bill to break through the planning and political quagmire holding back the construction of a third runway at Heathrow. It could also be applied to reservoirs, nuclear power, battery storage, and more. However, the Government should consider moving quickly with an AIGZ-focused bill, as a test case for wider infrastructure projects, particularly given the urgency of attracting current AI opportunities.

A new Building Britain Act represents the most ambitious approach for AI Growth Zones, but it is not the Government’s only option. Below we set out a number of possibilities that would speed up AIGZs and other data centre projects. The proposed environmental regime would ensure that these schemes could benefit our nature across the country.

Crucially, without a new consenting procedure, AIGZs will have to be approved under existing planning rules, and burdensome EIAs will have to be performed for every application, adding substantial time, legal risks and costs. That means that some of these recommendations are interlinked: using either an AIGZ Authority with planning powers or an improved NSIP regime (both discussed below) would struggle without a National Policy Statement or National Development Management Policy setting out the Government’s policy encouraging new data centres.

A new delivery body for AI Growth Zones

A major challenge for the development of AI Growth Zones is that, under existing rules, they would be required to secure planning approval from Local Planning Authorities. In many parts of the country, Local Authorities have become increasingly resistant to data centres, citing concerns ranging from their energy and water demands, to trade-offs with wider land uses, strains on local infrastructure, and noise and design issues.

The government has sought to tilt the balance of local decisions in favour of data centres through its December 2024 updates to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). These changes make clear that Local Authorities should 'pay particular regard to facilitating development to meet the needs of a modern economy, including by identifying suitable locations for uses such as… data centres'.

However, in practice, the rules around when data centres should be approved are not always clear cut and Local Authorities can be vulnerable to the objections of noisy but unrepresentative small groups locally, rather than the national interest. This creates a particular challenge for data centres, where some of the impacts - such as on energy and water demands - are felt locally but the benefits, in terms of supporting technological innovation and driving productivity and growth, are spread across the country. This could be partly mitigated by a better regime for local authorities to retain the business rates of new development. In other countries, including France, similar measures have been very successful in motivating local governments to want major projects.

Local Authorities are also resource constrained, meaning they are unlikely to have access to expertise on data centres and AI. If the government hopes to secure swift approval for AI Growth Zones once they are designated and to ensure permissions are built out quickly, one option for achieving this would be to establish a body which has a specific focus on delivering these zones and the necessary expertise.

The Tony Blair Institute suggested this could be done through a new AI Growth Zone Authority, with the power to oversee and coordinate planning and infrastructure delivery across AI Growth Zones.

We support the idea for this new Authority, especially if the Government continues to approve data centres via the regular planning system. In that case—in tandem with the suggested National Policy Statement or National Development Management Policy explained in more detail in the section below—it could be designed to overcome the challenges that are preventing the most nationally critical data centres being approved quickly through the current system, through having clarity of purpose, the right expertise and effectively balancing valid concerns about the designs of projects with the scale of their value to the UK economy.

Granting the Authority these powers would be a significant improvement over the status quo but would miss out on many of the advantages of the Building Britain Act. Those advantages include reduction in judicial review risk, a firm, cost effective and fast statutory basis and replacing individual EIAs for each project with a single, faster and more cost-effective SEA.

The design of the AI Growth Zone Authority should be modelled on the combined scope and roles of the Olympic Delivery Authority - which effectively developed several sites across London at pace for the 2012 London Olympics - and the London Legacy Development Corporation - which developed the Olympic Park after the games. For instance, it should have:

- A single mission to drive up the UK’s data centre capacity and ensure AI Growth Zones are delivered at pace, so the UK’s AI and technology sectors remain internationally competitive. This is vital as it means that the AI Growth Zone Authority could focus its resources on one core priority and wouldn’t need to balance competing objectives.

- Sufficient consenting, land assembly and financing powers to deliver the necessary infrastructure on site. Similar to the powers of development corporations, the Authority should assume the role of local planning authority for sites designated as AI Growth Zones. These powers should include the ability to compulsorily purchase land as necessary to remove barriers to development on the site and enter into financing arrangements with investors and developers to ensure sites can be built out quickly.

- Powers to work across multiple sites. Unlike development corporations, which tend to focus on one site, the Olympic Delivery Authority covered several sites across London, drawing on the same pool of expertise. Similarly, the AI Growth Zone Authority should act across all AI Growth Zones and as the planning authority for all new data centres. This would be much faster than having to establish governance structures for each individual AI Growth Zone.

- Clear accountability to Cabinet. Like the Olympic Delivery Authority, the Chair of the AI Growth Zone Authority should report directly to the relevant Secretary of State (likely at the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology). It should be staffed by a mixture of experts in planning, infrastructure delivery, project finance.

- A time limited life. The government is right to be concerned about the large numbers of various regulators and non-departmental public bodies with overlapping interests and scopes. This Authority should not add to that list but instead be a short-lived structure focused on supporting sufficient numbers of data centres to be approved and developed over the coming decade.

To implement this approach, the government would need to use primary legislation to define and create the AI Growth Zone Authority, in line with the suggested scope above. To ensure it could have maximum impact to speed up the delivery of AI Growth Zones the legislation should make the Authority the relevant planning authority for any area designated an AI Growth Zone.The legislation should make clear that the designation of an area as an AI Growth Zone automatically confers powers for planning consent, land assembly, infrastructure delivery and charging of developer contributions to the AI Growth Zone Authority.

Streamlining planning for AI investment

Planning approvals have to be made in line with planning policy, much of which is set directly by the Government. The Government has already announced that it will bring forward a National Policy Statement (NPS) for data centres. This is a positive step and will help large data centres navigate the NSIP regime. The National Policy Statement would, however, only be a ‘material consideration’ for data centres that are consented under the existing planning framework. The Government should also affirm its policy support for AI infrastructure in a National Development Management Policy (NDMP).

If the Government passed a Building Britain Act, also making an NDMP would help both smaller schemes and those that might not be eligible because they are outside designated zones. If the Government instead kept AIGZs within the regular planning systems—within the TCPA system, NSIP regime or with an AI Growth Zone Authority), robust policy encouraging their approval will be vital.

Critical national priority

The NPS and NDMP for data centres should declare that AI infrastructure are a ‘critical national priority’. EN-1, the Overarching National Policy Statement for Energy, applies this designation to ‘low carbon infrastructure’. This means that the Government considers that the country’s need for clean power ‘in general outweigh[s] any other residual impacts’ that can’t be mitigated. That is, planners should weigh the importance clean power has for beating climate change very highly when considering such planning applications. The Government should not include the ‘in general’ qualifier for data centres, strengthening the policy’s application.

National landscapes

In the Levelling-up and Regeneration Act 2023, the last Government strengthened the duty on planning decision makers when it comes to National Landscapes (formerly Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty) and National Parks. Previously they only needed to ‘have regard to’ the purposes of the protected areas, now they must ‘seek to further’. This is a significantly higher bar and the new duty has invited significant dispute over how much compensation is enough. In some cases, projects miles from any protected area have been asked to pay millions of pounds, making development more expensive and legally fraught. This duty would also apply to data centres.

There was no need for this. As Mustafa Latif-Aramesh has explained, planning policy already confers the 'highest status of protection' to these areas and permits consent only in exceptional circumstances. The new rules, brought in under the previous government, have led to substantial uncertainty and numerous judicial reviews. Adding a poorly defined statutory duty mainly increases process risk rather than improving environmental outcomes.

The Government has a few options to fix this small but disruptive issue, including:

- A carve out for AIGZs

In an AI focused bill the Government could vary the duty solely for AIGZs or data centres. - Policy mitigations

The Government should issue new planning policy that brings the duty in line with the Government’s pro-growth priorities. This could direct decision makers to consider measures and adaptations that further the purposes of the protected areas without imposing additional costs. Policy should make clear that additional costs should only be imposed where wholly exceptional circumstances apply.

Use a reformed NSIP regime

The NSIP regime is not ideal for data centres—or frankly for UK infrastructure writ large. The Government recognizes that planning for large infrastructure needs to be streamlined. Currently data centres are dealt with under the Town and Country Planning Act regime, but the Secretary of State can direct projects to proceed through the NSIP process under section 35. The government has announced data centres will, in due course, be capable of such a direction and we understand the Government is planning to use the NSIP regime for the largest data centre projects.

We believe that the Building Britain Act would be an extremely powerful route, and an improvement over NSIP. If the Government cannot make a new consenting route for AIGZs, it should consider significant reforms to the NSIP regime to ensure it delivers quicker decisions. This would be particularly effective if the Government issued a strong National Policy Statement for data centres and growth zones as suggested above.

The Government should reduce the burden of pre-application consultation and tighten timelines for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) to speed up decision-making. Though flawed, the NSIP process is still preferable to the regular planning system for large projects. It is already making progress on improving the process with the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, which will reduce the burden of statutory consultation. However to make it truly fit for purpose the Government will need to go further. The Government should restore the one-stop shop that was the original promise of a DCO. The best way to do this would be to remove section 150, which currently allows a DCO to disapply prescribed consents only with the agreement of the relevant consenting body—giving external regulators an effective veto over rolling their permits into the order. Failing primary legislation, or in the meantime to make progress this Parliament, the Government should tighten its guidance to force the regulators to consider issues concurrency with the DCO process: one list of issues agreed between regulators and PINS, joint hearings, model conditions, and a presumption against duplicate consultations.

An NPS, discussed above, could codify the national 'need' and set out standard mitigation so the residual approvals are largely mechanical. An NPS cannot, however, itself impose binding statutory clocks, fold those permits into the DCO, or guarantee a single JR window.

The Government should also tighten the timelines and expectations for the decision making process once an NSIP has been submitted:

- Introduce time limits for the pre-examination period

Primary legislation could amend section 88 to require the preliminary meeting within four weeks of the applicant’s certification. Without primary legislation, guidance could be updated to reduce the presumed 5–8 week pre-examination period. The guidance should also be amended so that the examining authority can issue advice on applications it would otherwise refuse on how to rectify any issues. This would let applicants fix problems early rather than be refused and forced to start again, saving months. - Reduce the examination period

Primary legislation could amend section 98 of the Planning Act 2008 to shorten the statutory examination from six months. Guidance could be used to direct Examining Authorities to plan for a shorter timeline by default, using the full six months only in wholly exceptional cases. - Require SoS to issue questions earlier

When deciding an application, the Secretary of State can respond to an applicant with questions. Currently these are often released right up to the decision deadline. The Government should instead require these at the two month point. This can be done with secondary legislation. - Require a 'minded-to' letter on decision delay

Currently, the Secretary of State has three months to decide a DCO, but can extend that by making a statement to Parliament. The Government should require that, when delaying a decision, the SoS issue a ‘minded to’ letter, effectively setting out which way they are leaning. This would reduce uncertainty, signal the remaining issues to fix, and curb open-ended extensions by committing the SoS to a clear direction and next steps. - Give the PM oversight of approvals

Number 10 should actively coordinate all NSIP applications and decisions. A dedicated team should track every scheme end-to-end, enforce statutory clocks, and broker cross-regulator issues. Where a department seeks to extend a deadline or impose novel requirements, the case should be escalated to a PM-chaired approvals committee with authority to direct regulators and settle disputes within two weeks.

These reforms would also benefit all major infrastructure projects in the UK, many of which (e.g. clean power and water infrastructure) are vital for data centres in the long run.

Environmental regulation

A slow planning system is not the only issue holding back new data centres in Britain. The distinct legal system of environmental and habitats rules require extremely long assessments, running to thousands of pages and years of work, and can then require extremely costly mitigations. The well-known HS2 bat tunnel and Hinkley fish disco were not results of planning, but of environmental and habitats dysfunction.

Our rules surrounding environmental and habitats protection have become burdensome and overly process-driven without ensuring that overall environmental outcomes are improved. Even before an assessment is begun, a screening opinion can often take months, and EIA regulations lack specific thresholds for data centres. The Environmental Impact Assessments themselves involve long seasons of baseline survey work, iterative scoping and re-scoping, and ever-wider expectations around cumulative and downstream effects. Full Habitats Regulations Assessments can be triggered for even modest works where the regulator can point to a potential, and often spurious, route for endangered species to get from a protected site to the project.

The mitigations demanded by these rules are often worse for nature overall than cheaper schemes to deliver stronger and more cost effective benefits nationally. Our proposals learn from effective examples across Europe, as well as lessons from effective British protections for newts. The Government needs to reform our rules, putting the environment and speed as priorities over endless meaningless and costly process that does not deliver good outcomes for the environment or for the nation as a whole.

For large data centres, where investment is mobile and delivery windows are tight, the delay and uncertainty can be catastrophic. Developers cannot know in advance what evidence will be 'enough', when the critical surveys can be completed, or how many cycles of consultation and further information will be required. The case for reform is not to lower standards, but to make them proportionate, outcome-focused, science-based, and time-certain, with more certainty that they will deliver overall environmental and social benefits.

In the next two sections, we set out our proposal for a new way of approaching EIA for the largest growth zones, which should be included in the Building Britain Act, and a standard template to accelerate Environmental Delivery Plans to ensure a good deal for protected species. We also set out other fixes that will help smaller data centres, and will work quickly before a whole new regime is in force.

Unlike the broader proposals in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, these suggestions only apply to a very limited number of sites, which will only be brownfield unless the Secretary of State determines otherwise in a specific case. Given this very limited application of our proposals, we believe that a more efficient approach is appropriate and necessary, particularly where contributions can help to improve nature across the country.

A strategic approach to environmental protection

Development in AI Growth Zones will be fastest, while ensuring environmental improvement, if the Government completes a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the area. This single assessment front-loads the work of understanding likely significant effects once, up-front, instead of re-litigating the same issues scheme by scheme. This approach requires primary legislation to deem that the completed SEA disapplies the requirements for individual EIAs for subsequent development, and is one of the major advantages of the Building Britain Act. Under the Act, the Government or city-region mayor should prepare an SEA before it designates AIGZs. The environmental rules and mitigations can then be incorporated into the designation to create a pro-nature set of bright line rules for the zones. The work of producing the SEA should be done in advance of designation

The SEA sets the groundwork for the designation. The assessment would be higher level than an EIA, considering the proposed zones as a whole. The Government can set out clear rules for developments within the zone to ensure overall benefit for nature. These might include:

- Limits on heights or total footprint

- Limits on the power draw of a data centre

- Excluded areas, for example if parts of the site are extremely sensitive

- Required mitigation measures for the effects that can most effectively be dealt with on site

Crucially the plan must also require developers to pay an Environmental Improvement Levy to ensure the scheme results in an overall environmental benefit. This would be calculated based on the scale of development and would be paid into a dedicated fund used to mitigate the environmental impacts, including off-site mitigation where that is most effective. This then means development within the zones would simply need to comply with the bright-line rules, including payment of the levy, not go through a slow and uncertain EIA process.

This process creates a win-win for the environment and for society. Schemes are still required to deliver on-site mitigation where it is identified as most appropriate under the SEA, but pooled and off-site schemes are available to ensure outcomes for nature are improved without slowing down projects. There are a number of international examples of such a model being effective:

- Evaluation of Britain’s District Level Licensing scheme for great crested newts has shown that it has created habitats that become thriving homes for newts more often than on-site schemes.

- Denmark has a pooled, national marine nature fund that will finance large-scale, strategic habitats restoration which smaller, scheme level mitigations would be unable to cover.

- In 2020, France accredited a 357ha steppe restoration project at the La Crau steppe near Arles. This allows developers to purchase ‘compensation units’, offsetting local harms by improving the environment in a very sensitive area which has seen target species return. The accreditation requires CDC Biodiversité to show sufficient land control and finances to manage the site for at least 30 years.

We are confident that this plan would not be considered a ‘regression’ under either the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement or the Environment Act 2021. Many countries in Europe have schemes that mirror our proposals here, none of which have raised regression issues under the TCA:

- The EU has granted member states the ability to ‘introduce exemptions from certain assessment obligations set in Union environmental legislation for renewable energy projects and for energy storage projects and electricity grid projects that are necessary for the integration of renewable energy into the electricity system.’ subject to two conditions: ‘that the project is located in a dedicated renewable or grid area and that such area should have been subject to a strategic environmental assessment.’ This was initially introduced in regulation 2022/2577 in response to the Ukraine War, but made permanent and binding on states in 2023 with the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED III).

- Germany transposed EU regulation 2022/2577 by amending its Spatial Planning Act. This allowed states to designate ‘wind energy areas’, subject to an SEA. In these areas developers are not required to conduct specific EIAs or species protection assessments, so long as they comply with certain conditions. Germany’s rules also include provisions for developers to pay a fixed levy where the environmental authorities are not otherwise able to secure suitable and proportionate mitigation measures. This levy is calculated based on the megawattage of the scheme.

- Spain created a simplified regime to authorise renewable energy projects that streamlined environmental assessment outside of specifically protected sites.

The reasons why the EU’s approach does not constitute a regression are the same reasons why a similar approach by the UK would not:

- The proposal is inherently limited in application

- Environmentally sensitive sites are excluded

- There will be funding to ensure an overall enhancement in nature

The SEA would apply the precautionary principle: ministers and mayors would consider what the ‘likely significant impacts’ of a data centre would be on the site. This means that the assessment assumes significant effects where there is material doubt, and tests reasonable alternatives for how the zone is planned. The assessment would include public consultation and sets the evidence base for the later designation, ensuring decisions are grounded in best scientific evidence and that mitigation is designed at the right scale from the outset.

The bill would also provide for a screening mechanism, modelled on the German system, to ensure that proposed development is compliant with the assumptions of the SEA and rules of the designation. As with the German process, the bill should include a statutory presumption that there are not significant effects that were not foreseen by the SEA, i.e. that the development should not also require an EIA . This will ensure the screening process moves quickly. The screening opinion should be given by the Secretary of State, or by the relevant mayor who designated the zone.

A template EDP

The Strategic Environmental Assessment associated with a designation would mean that developers would be discharged of their EIA requirements, but they would still be required to complete and comply with full habitats assessments. The Planning and Infrastructure Bill gives Natural England the power to create Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs): area-based plans that identify the features likely to be affected, set out a conservation programme, and include charging schedules for a nature-restoration levy. An EDP can lawfully use off-site measures where these deliver greater benefit to the same feature than on-site actions, must include contingency measures to be triggered by monitoring, and is consulted on (but does not itself require SEA).

For AIGZs, the Government should direct Natural England to produce a template EDP that can be quickly tailored to each zone. This would include a mandatory levy, with the size calculated to deliver an overall improvement given the scale of development. Once a developer commits to pay the levy, the specified habitat and protected-species effects covered by the EDP are legally disregarded and the developer is treated as licensed. This removes the need for project-by-project licensing within the zones.

Other changes to environmental regulation

Take back the power to amend EIA regulations

In the Levelling-up and Regeneration Act, (LURA) the last Government removed the power it had to amend the Environmental Impact Assessment regulations. Other European countries often update their own rules. Though the Government still plans to replace EIA with a new system—Environmental Outcomes Reports—this is a slow process. In the meantime, the Government is stuck, unable to fix any issues.

We propose several reforms that the Government could make to EIA below which, taken together, could significantly improve the speed of delivery both for AIGZs and other major projects. As a first step, however, the Government will need to use primary legislation to restore the lost power to update the rules to reflect changes in technology and the economy.

Change the thresholds for data centre EIA

At present, uncertainty over whether a data centre project requires an Environmental Impact Assessment drives local authorities into default screening. This chews up months only to conclude either that no EIA is needed (after needless delay) or that one is, with scopes that are often disproportionate.

Regulations set out a list of project types, with thresholds for what is considered ‘EIA development’. For example, housing developments of over 150 homes or 5ha require an EIA. But the current rules do not explicitly set out the Government’s expectations for data centres. Instead they are lumped under ‘Industrial Estate Development Projects’ meaning the thresholds do not map neatly onto AI projects.

The Government should review and set specific EIA thresholds for data centres on brownfield sites, taking into account their lack of emissions.

After using an Act to restore the power to update the rules, the cleanest mechanism to do the above is a short amendment to the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 to add a bespoke Schedule 2 category: 'Data centre development projects.' This new line would carry clear, objective, and high thresholds. These might be based on megawattage or floor area. Outside sensitive areas, proposals below those thresholds would not require EIA. Within sensitive areas, screening would still be undertaken, but it would be measured against guidance that recognises the characteristic risk profile of data centres rather than forcing them into ill-fitting industrial estate tests.

Policy should then anchor proportionate practice. In our proposed new National Policy Statement, ministers should specify the limited set of impact topics that typically matter for data centres (e.g., noise, water use and discharge, energy supply and resilience, and townscape/visual where relevant), and make clear that Scope 3 emissions are out of scope for EIA purposes. The same policy should direct substantial weight to the sector’s digital and economic benefits, and provide a streamlined Environmental Statement template for the minority of schemes that still require EIA, with standard mitigations set out in policy.

The Government should also give the Secretary of State a narrow power to quash or vary screening opinions that clearly misapply the policy (with a rapid timetable), publish a standard screening checklist for planning authorities, and require statutory consultees to respond within tight timeframes.

Clarify the effects of the Finch judgment

The Supreme Court’s decision in R (Finch) v Surrey County Council [2024] held that an EIA for an onshore oil extraction project must assess the greenhouse-gas emissions from the foreseeable combustion of the oil ultimately produced (described as an ‘indirect effect’ of the extraction). That is, decision-makers must assess the pollution released when the oil is later burned by end-users. In the case in question the council had not done so and thus their decision to accept the assessment was found to be unlawful. AI Growth Zones do not produce fossil fuels and data centres connected to the UK grid are likely to be significantly cleaner than a counterfactual project elsewhere in the world. The Finch judgment does however create legal uncertainty for developers.

The Government could remove this uncertainty by clarifying planning guidance for new data centres in AI Growth Zones. Guidance should say explicitly new digital infrastructure projects do not need to consider any downstream Scope 3 emissions when completing an EIA or SEA. This would not reduce the level of environmental protection—any project assessment would still need to assess the full Scope 2 emissions of the data centre’s electricity consumption—but would provide certainty for developers and the Government. This will, overall, be better for the climate: the UK’s rules on emissions are among the strictest in the world. Any data centre not built in the UK is likely to instead be built in a country relying on fossil fuels. The data will still travel across boundaries, as will the climate effects.

Habitats Regulations for AI Growth Zones

Habitats Regulations are currently extremely poorly implemented, and the effects are felt keenly on projects like AI Growth Zones. They completely fail to ensure either that the environment is improved as much as possible or that beneficial development can proceed efficiently, which would generate more jobs and Government revenues with which to improve public services. This is, in part, because the Regulations’ interpretation gives primacy to hypothetical risks without scientific backing. Commentators have written in detail about various examples of this, arguing that we should deliver better outcomes for nature with a better-structured regime. We endorse the proposals from Catherine Howard on this, as well as further measures. Each of them would make marginal but appreciable improvements to the regime, while still maintaining an exacting and science-based set of natural protections. These include:

- Requiring that Statutory Nature Conservation Bodies (such as Natural England) adopt a science-based approach

In making their assessments of development proposals, these bodies should be required in law to draw on scientific evidence and scientific justification to determine what risks proposals could create. Currently, many of the conditions and requirements for evidence gathering are based on hypothetical risks, which add substantial time and costs to projects without reflecting any genuine risk to nature. - Removing the requirement to prove a negative

Under current regulations, authorities may only approve a scheme plan ‘only after having ascertained that it will not adversely affect the integrity of the European site’. This means that even where there is no positive evidence of a risk at all, lengthy surveys and expensive mitigations may be required to attempt to robustly show that it is not possible that there could be any risk (which is challenging scientifically). The Government should amend the regulations to remove this, allowing schemes unless there is scientific evidence of a risk to nature. This would align with the usual burden of proof under law. - Letting secured mitigations count during screening

The Government should reverse the outcome of the ‘People Over Wind’ case in 2018 by allowing screening to take account of secured mitigation. This would mean that when deciding whether a full assessment for a project is needed, the judgment on the impact of the project would take into account the proposed mitigation measures. - Clarifying that de minimis impacts can be acceptable

Currently, a single, potential fish or snail death could be considered an unacceptable adverse effect to the integrity of the site even if there is substantial uncertainty in the assessment. The Government should introduce legislation to clarify that de minimis impacts can be acceptable, based on the overall benefits of the project, so that resources can be focused on the most important issues for nature. - Removing the need to re-do habitats assessments for approval of conditions

After consent, projects still need small sign-offs (e.g., construction methods or seabed cable-repair plans). These routine approvals shouldn’t trigger a fresh, full Habitats Assessment if the original consent already covered the effects. The Government should remove this duplication to ensure resources can be directed to where there are genuine risks to nature. - Defining key terms such as 'alternative solutions', and 'imperative reasons of overriding public interest'

Many projects, where they cannot show there is no adverse impact, will have to show there are no alternative solutions, and also that there are imperative reasons of public interest for the development. Tweaks to make clear that AIGZs are sufficiently important that other AI infrastructure in other locations shall not constitute an alternative, and that AI infrastructure will always constitute an 'overriding' interest should be legislated, or if that is not possible, clearly spelt out in any National Policy Statement (as is the case for low-carbon infrastructure in the Energy National Policy Statements).

Our proposed bill would allow the government to follow the more powerful German approach on Habitats Regulations.

JR reform for AI Growth Zones

Judicial review (JR) is vital to ensuring that Government decisions follow the rules set out by Parliament, but for major infrastructure projects it often functions as a process multiplier and delay magnifier. Every civil servant working on a scheme is acutely aware of The Judge Over Your Shoulder: the official guide to avoiding JR risk. This means that, even before a claim is lodged, officials gold plate processes to guard against challenge. Once a complaint reaches the court, all of this has to be meticulously, and slowly, checked.

This applies for every large scheme, but for an AI Growth Zone, delay and risk could come with massive costs. The global race for capital, and for equipment, means investors have international options. A single late-stage challenge can push a scheme past procurement windows or investment committee cycles and send it abroad. The Government needs to reform Judicial Review to keep a clear route for genuine failures to be challenged in court while ensuring that challenges are brought once, heard quickly, and resolved finally.

Government thinking has moved in the right direction. Following Lord Banner KC’s review, ministers have consulted on fewer 'bites' at permission, a specialist Planning Court listing, earlier case-management, and published performance data, alongside measures in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill. These steps should be taken forward for all NSIPs.

But these reforms do not go far enough. Given the speed required, and the cost of delays, the Government should strengthen its proposed reforms for AI Growth Zones specifically to ensure that only legitimate claims are heard.

- One-window, one-shot challenges

Require all public-law challenges to an AIGZ designation (or an AIGZ-relevant DCO decision if the Government uses the NSIP route) to be brought in a single claim within a short window, with later implementing steps only challengeable on narrow ultra vires grounds. - Guaranteed fast track

Create an AIGZ/JR track with permission decided swiftly, rolled-up hearings listed within weeks, and judgments delivered to a fixed timetable, enforced through listing priorities and issue-narrowing directions. - Proportionate remedies by default

Make suspended or conditional quashing orders the norm so curable defects are fixed without collapsing the consent, with relief refused where errors made no substantial difference. - Controls on repetition and interventions

Bar repeat claims by the same actors on issues already determined absent genuinely new evidence or law, and allow interventions only where they add distinct value on a costs-neutral basis.

These reforms would leave judicial review intact but make it quick, concentrated and decisive for AIGZ-critical decisions, improving delivery for data centres immediately while raising the standard for other nationally significant infrastructure.

Power

Data centres already represent a sizable proportion of UK power consumption. The National Energy System Operator (NESO) estimates current electricity consumption from data centres to be 5 TWh p.a. (or c. 2% of UK electricity consumption). They expect this to rise more than fourfold, to 22 TWh p.a., by 2030. This may be an underestimate given it was based on planning and grid connection applications when the Clean Power 2030 report was delivered in 2024.

It is not just the quantity of electricity demand that matters, but also the profile of that demand. Data centres require extremely reliable power: 'five nines' of reliability is the industry standard, meaning 99.999% up time, or just 5 minutes per year of interruption. In the case of AI driven demand, inference is likely to peak during the working day and is unlikely to have a major seasonal bias. Training AI models is likely to be even more demanding for the UK grid - SemiAnalysis has described the potential risks and demands that large scale AI data centres place on the grid via rapid and sizeable power demand fluctuations.

Data centres are also capital intensive - 2024 estimates from Turner & Townsend suggest construction costs of around $11m per MW for data centres in London and Cardiff. The capital costs of AI data centres, with expensive GPUs, higher power densities and advanced cooling techniques are likely to be higher. Given the £bn+ costs required to construct these sites, owners are incentivised to run them at high utilisation rates, limiting the scope for dramatic electricity demand reductions based on fluctuations in renewable generation and wholesale electricity prices.

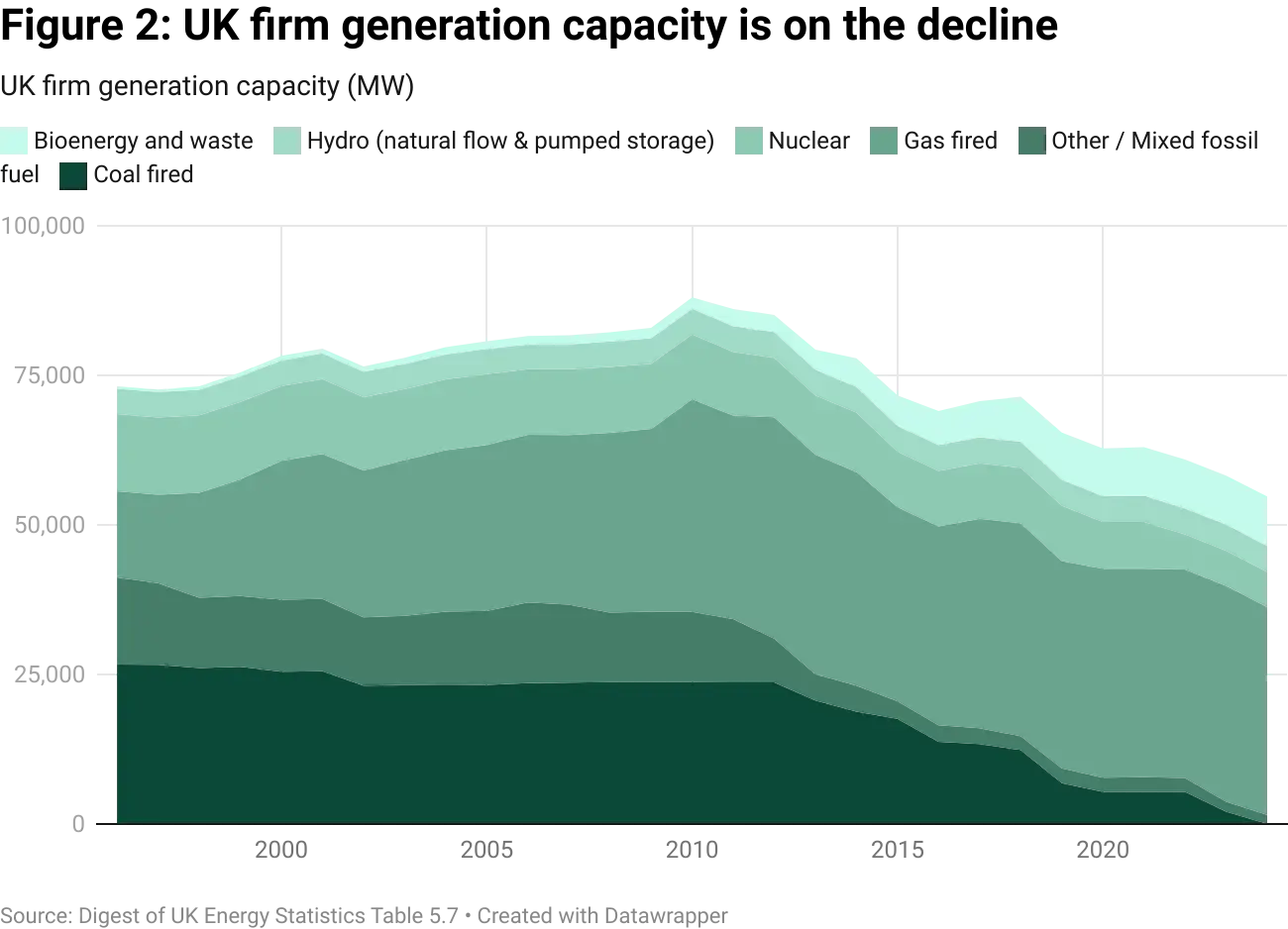

The UK is poorly positioned from a firm power perspective. The chart below shows the capacity of firm and dispatchable generation in the UK since 1996.

Looking forward, the picture isn't reassuring, particularly for low carbon firm power sources. UK nuclear capacity is likely to fall by about 40% from current levels by 2029 as older, gas-cooled reactors go offline. New pumped hydro projects, such as Coire Glas, are highly unlikely to appear before 2030, leaving expensive options such as gas CCUS. NESO does anticipate substantial growth in data centre power consumption, but faster than anticipated demand will place the grid under pressure without additional supply.

Additional firm electricity generation must go alongside any significant build out of data centre demand. Failing to do so risks driving up wholesale electricity prices and capacity market costs, creating political friction between data centre investment and hard pressed residential electricity consumers.

Grid connections

Lack of low-carbon firm generation capacity is not the only barrier to building AI infrastructure. Large data centres will ultimately require a physical grid connection, even if built with colocated power generation. A grid connection provides increased power reliability, and the ability to participate in the balancing mechanism. Very large data centres and AI Growth Zones will need to connect into the high voltage transmission network rather than the lower voltage distribution system.

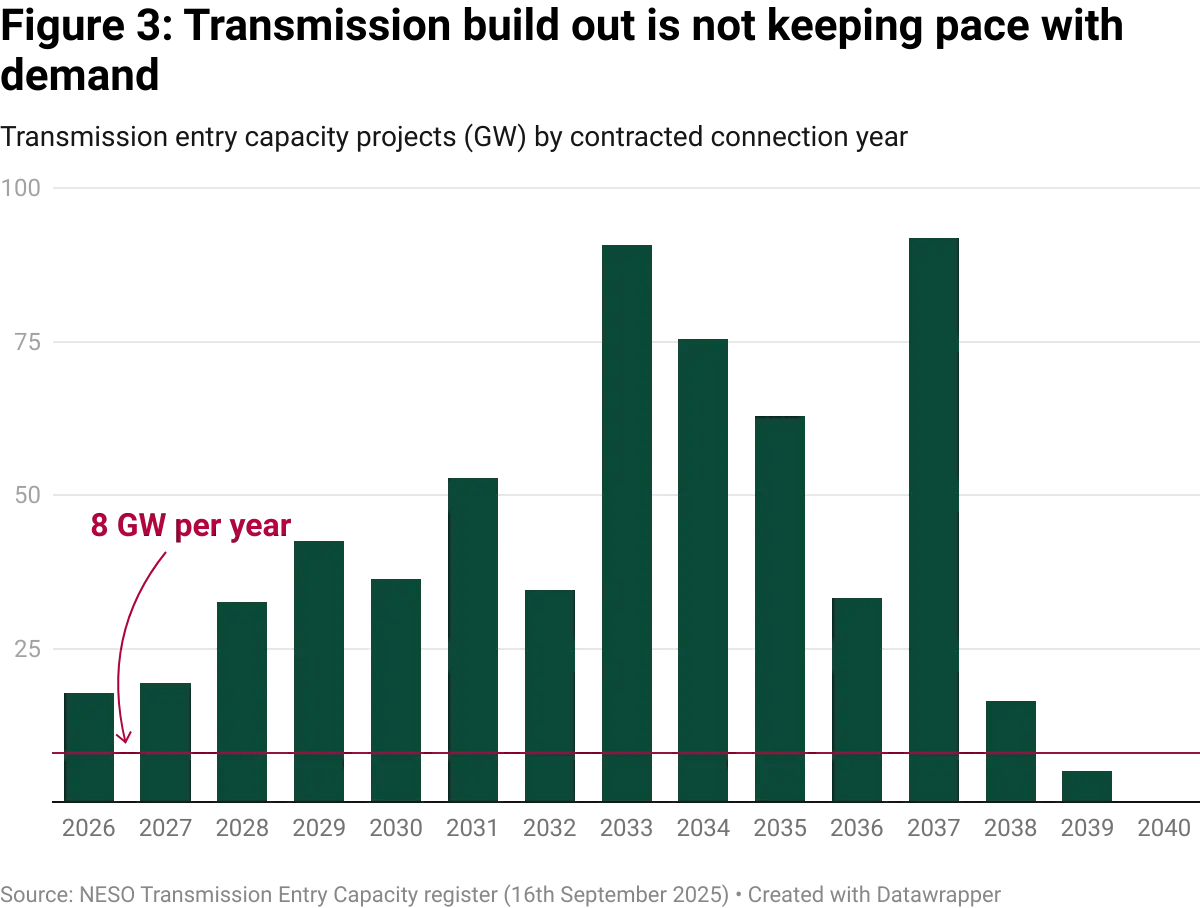

The UK has a major bottleneck with respect to grid connection - over 800 GW of potential projects sit in a queue, which until recently was delivered on a ‘first come, first served’ basis, giving no weight to the plausibility of each project. The chart below shows when transmission operators have agreed to connect generation and storage projects to the grid. The plans already extend into the late 2030s, but even this understates the problem. The historic rate of connection delivery has been just 8 GW per year, meaning that, on current trend, even these slow grid connection agreements are unlikely to be delivered.

In April 2025, Ofgem approved a series of connection reforms known as TM04+. These changes will help streamline the connection queue by prioritising projects that can demonstrate readiness and need.

Whilst these connection reforms are welcome, they are unlikely to remove the friction associated with grid connection. Ofgem anticipates a gate 2 (prioritised) connections queue of 296 GW following the reform package. Fundamentally this will still be a queue based system, taking no account of the economic value of different projects that might be revealed by a price or auction based system.

Speeding up deployment: Recognising the constraints

The Government’s technical criteria for AI Growth Zone applications recognises these constraints: sites must demonstrate not just sufficient land control, water access, digital connectivity and planning feasibility but also access to at least 500 MW of power capacity by 2030. This can be via a sufficiently large grid connection or behind the meter power.

Culham, in Oxfordshire was chosen as the UK’s first AI Growth Zone thanks to its unusual grid connection status. It benefits from an existing connection left over after the recent decommissioning of an experimental fusion reactor. This unique circumstance is not a scalable solution for the UK’s broader AI infrastructure build out.

We believe that a successful AI deployment strategy needs to address three key concerns from a power supply perspective. Firstly, it must speed up the deployment process, by either alleviating or removing the grid connection bottleneck. Secondly, it should bring additional power supply to the UK generation mix, so that UK capacity margins remain robust and thirdly it should have a pathway to clean power generation.

Increasing competition in transmission connection

The government has already promised to deliver a Connections Accelerator Service to streamline grid access for major investment projects. Whilst this may help deliver major data centre investment by 2030, increasing competition in transmission connection should help increase capacity in the long term.

Competition in the lower voltage distribution network has meaningfully improved in the last 20 years. 2004 marked the issuance of the first Independent Distribution Network Operator (IDNO) licences and they are now thought to be adopting 70-80% of new connections. IDNOs are licensed to develop, operate and maintain connections to the distribution network, providing an alternative to contracting with the regional distribution monopoly.

There are a number of benefits for project developers. Firstly incentives for connection are well aligned: independents can only grow their revenues by adding new connections. Secondly, many independents have the licences to bundle multiple utility connections—e.g. gas, water, electricity and fibre connectivity—acting as a ‘one stop shop’ for their customers.

Narrow elements of competition have been introduced to the higher voltage transmission network - for example:

- Offshore transmission assets are built and financed by offshore wind developers under a ‘generator build’ model, before being transferred to a licensed offshore transmission owner (OFTO) to maintain and operate the asset.

- A Competitively Appointed Transmission Owner (CATO) is an attempt at an onshore equivalent and has been consulted on for over a decade. Requests for tender must be initiated by NESO and are subject to qualifying criteria - projects must be wholly new, separable, have network need and show consumer benefit. In April 2025 Ofgem was unable to confirm the needs case for the first CATO pilot project.

- User Self Build agreements allow customers to build their own connection assets up to 2km in length. The agreements are bilateral between the customer and the transmission owner, with the assets passing to the transmission owner post construction. Code modifications are being considered which could remove the 2km limit.

The UK should make three changes to improve competition in transmission connection:

- The User Self Build distance limit should be increased or removed, to increase the number of sites that would be feasible for new infrastructure.

- The UK should also legislate to introduce a new class of onshore transmission licence - the Independent Transmission Network Operator (ITNO) to mirror the role of the IDNO in the distribution system. This would improve the rate of connection delivery by introducing new actors that are better incentivised to build new transmission infrastructure.

- Leverage private capital to build new Grid Supply Points to enable transmission connected private wire networks. This idea, the Growth Zone Transmission Interface (GZTI), is explained below.

Further acceleration: The Growth Zone Transmission Interface

Section 4 of the Electricity Act 1989 prohibits the generation, transmission, distribution and supply of electricity without a licence. Constructing and operating onshore substations that connect to the 275/400kV transmission network is currently restricted to monopoly transmission operators.

Section 5 of the 1989 Act concerns the process of exemptions from licence requirements.

The Electricity (Class Exemptions from the Requirement for a Licence) Order 2001 is the secondary legislation that details the exemptions from licence requirements for generation, distribution, supply and transmission. Only one exemption for transmission exists, under Schedule 5 (1) Array Transmission, which creates an exemption for offshore wind transmission arrays.