Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. The responses

- 3. Conclusions

- 4. Authors

- 5. Methodology

Summary

In 2024, with a new Government elected, we conducted our first UK Growth Survey. This was specifically commissioned to help support the growth mission, which underpins the Government’s wider priorities. One year on, as the UK continues to struggle with low growth and a looming fiscal gap, we polled over 100 economists, researchers and policymakers to identify what the Government needs to do now to drive growth. Our results show some key themes:

- Build, build, build: Britain’s economic stagnation is a crisis of building. This has its roots in our planning system, which does not enable enough development, whether it’s houses in London, nuclear energy in Wales, or a metro in Leeds.

- A tale of two countries: Britain has two parallel economies. London (& the Southeast) has high productivity but lacks housing, meaning workers cannot move near jobs. The rest of the country suffers from crumbling transport infrastructure, expensive energy (hampering investment in manufacturing and AI) and decades of underinvestment.

- Energy is underrated but also difficult: Britain’s energy costs – among the highest in the world – reduce real household incomes, hamper industry and mean we’re losing out on AI investment. But there are few easy, short term fixes to reduce bills: instead the Government should take medium-term bets on new nuclear technologies, through fixing regulation, as well as expansion of grid connections and transmission.

- Fiscal constraints are real, but not insurmountable: our responders were clear-headed about the lack of room for extra spending, and the need to raise revenue. They also pointed to various ways to do this: the most preferred options were property taxes and fuel duties.

- There are free lunches out there: many of Britain’s ills are self-imposed. Building more houses and infrastructure, attracting investment and improving market dynamism can be achieved through regulatory and legislative reforms, rather than state spending. The UK’s potential for catch-up growth is enormous. Allowing the South to build more, funded by locally generated value, would free more resources for investing in other regions.

The responses

1. Political priorities

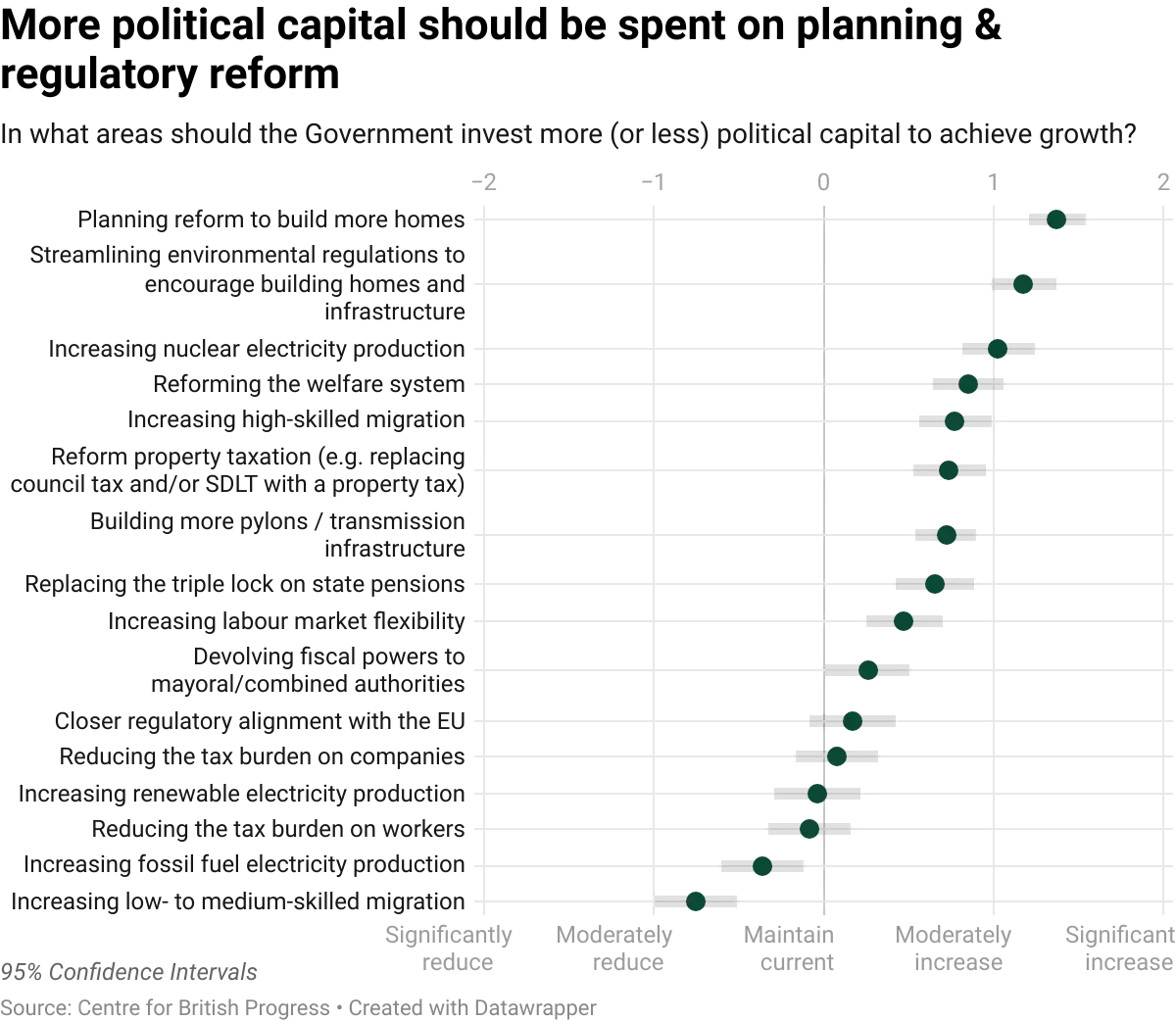

We asked responders what the Government’s political priorities should be. This was defined as being willing to take on special interest groups, internal or external political factions or even voter groups for the sake of achieving growth. We asked respondents not to answer in terms of spending priorities.

The two highest ranked political capital priorities related to building more: planning reform for homes, and streamlining environmental regulations for both homes and infrastructure.

Respondents were also generally keen on the Government spending political capital on increasing nuclear electricity production and high skilled migration, reforming welfare and property taxation, and replacing the triple lock on state pensions. They were less keen on spending political capital on increasing non-high skilled migration or increasing fossil fuel electricity production.

One respondent advocated nuclear investments despite the time and cost of building new capacity, saying: “[Energy] prices are going to bite… you may as well make long-term gains if you're going to take the hit anyway.”

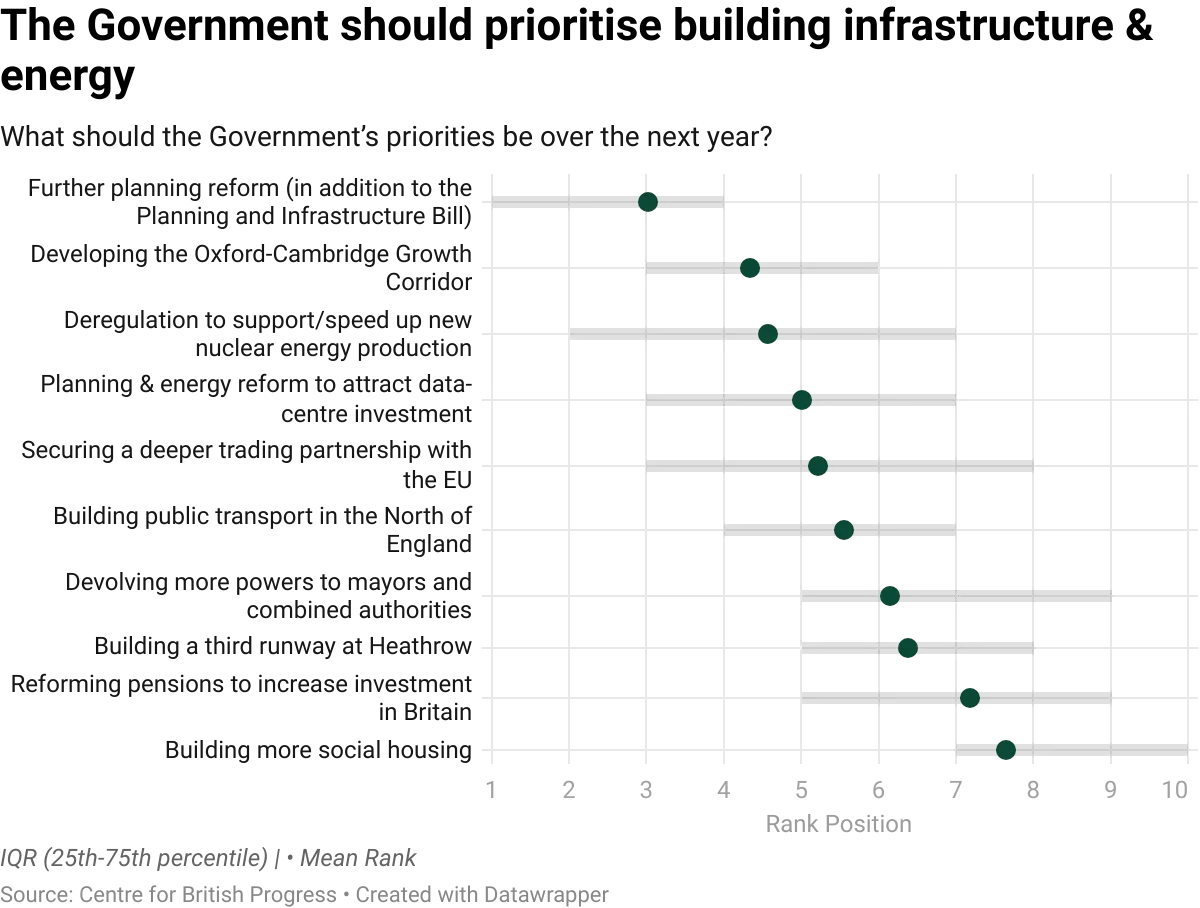

We asked respondents for more specific thoughts on what the Government should prioritise over the next year. Further planning reform was by far the top priority, followed by regulatory reform to encourage nuclear energy and data centres. Respondents were generally keen on the Oxford-Cambridge growth corridor proposal, but less sure about the growth benefits of prioritising building social housing, or of reforming pensions to encourage investment in the UK (though there was notable disagreement on this final point).

In freeform answers, responders emphasised the priority of building more homes and infrastructure, and using planning and regulatory reform to unlock investment in these areas. Others highlighted NHS and tax reform as top priorities. In general, there was suspicion about the benefits to growth from extra government spending, and more optimism about the potential from regulatory and planning reform. In the context of constrained public finances, this is welcome news.

2. Fiscal priorities

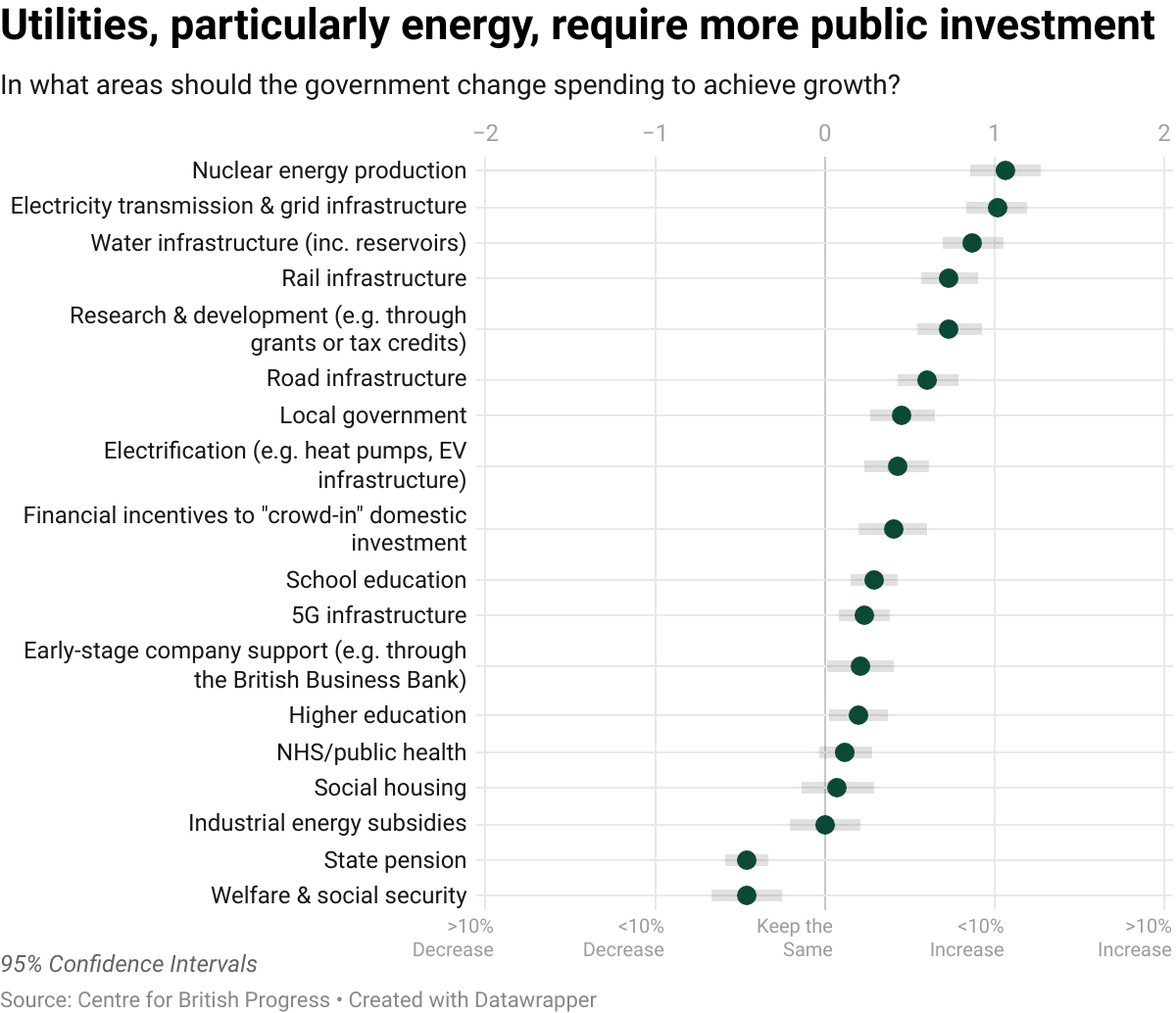

In terms of Government spending , respondents were generally in favour of spending more on utilities; particularly nuclear investments, transmission and grid infrastructure, and water infrastructure. After that came transport, R&D and road infrastructure. Respondents broadly favoured reducing spending on the state pension and social security.

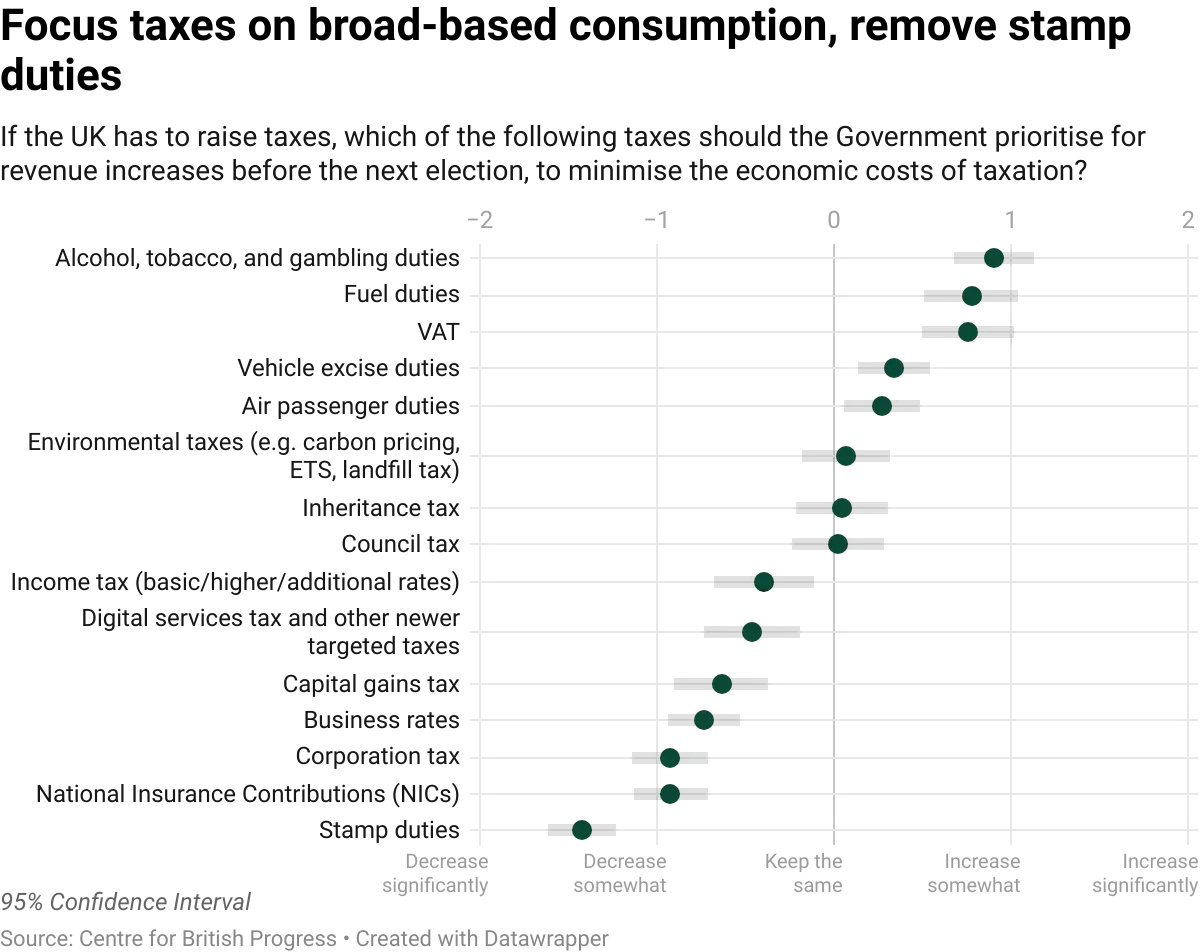

The Government faces a fiscal gap of £20-40 billion, and must therefore find ways to raise revenue in this year’s Budget. We asked responders which tax levers would be least costly (or most beneficial) from a growth perspective. Note that we did not ask them to include redistributive or political considerations.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, our responders preferred increasing consumption taxes over other taxes. In particular, those which have negative externalities (such as alcohol, tobacco, gambling, driving and flying), and Value Added Tax (VAT), which has a broad base on all sorts of consumption. Several respondents proposed some form of road tax to improve traffic and fund public transportation.

Meanwhile, responders were least keen on using stamp duties (such as Stamp Duty Land Tax), National Insurance Contributions (NICs) and taxes on businesses or capital gains to raise revenue.

In freeform answers, several responders mentioned removing VAT exemptions to improve revenue from this broad base. A number of responders highlighted the need to replace Stamp Duty Land Tax with a proportionate property tax, to improve long run revenue and reduce housing market inefficiencies. Others similarly highlighted the economic rationale of taxing land, which not only helps incentivise productive land use, but is also hard to avoid (as land is immovable). Lastly, several people mentioned that our tax system is too complex, too burdensome, and includes too many cliff-edges, which can lead to distortionary behaviour and less revenue for the Exchequer.

3. Strengths and weaknesses

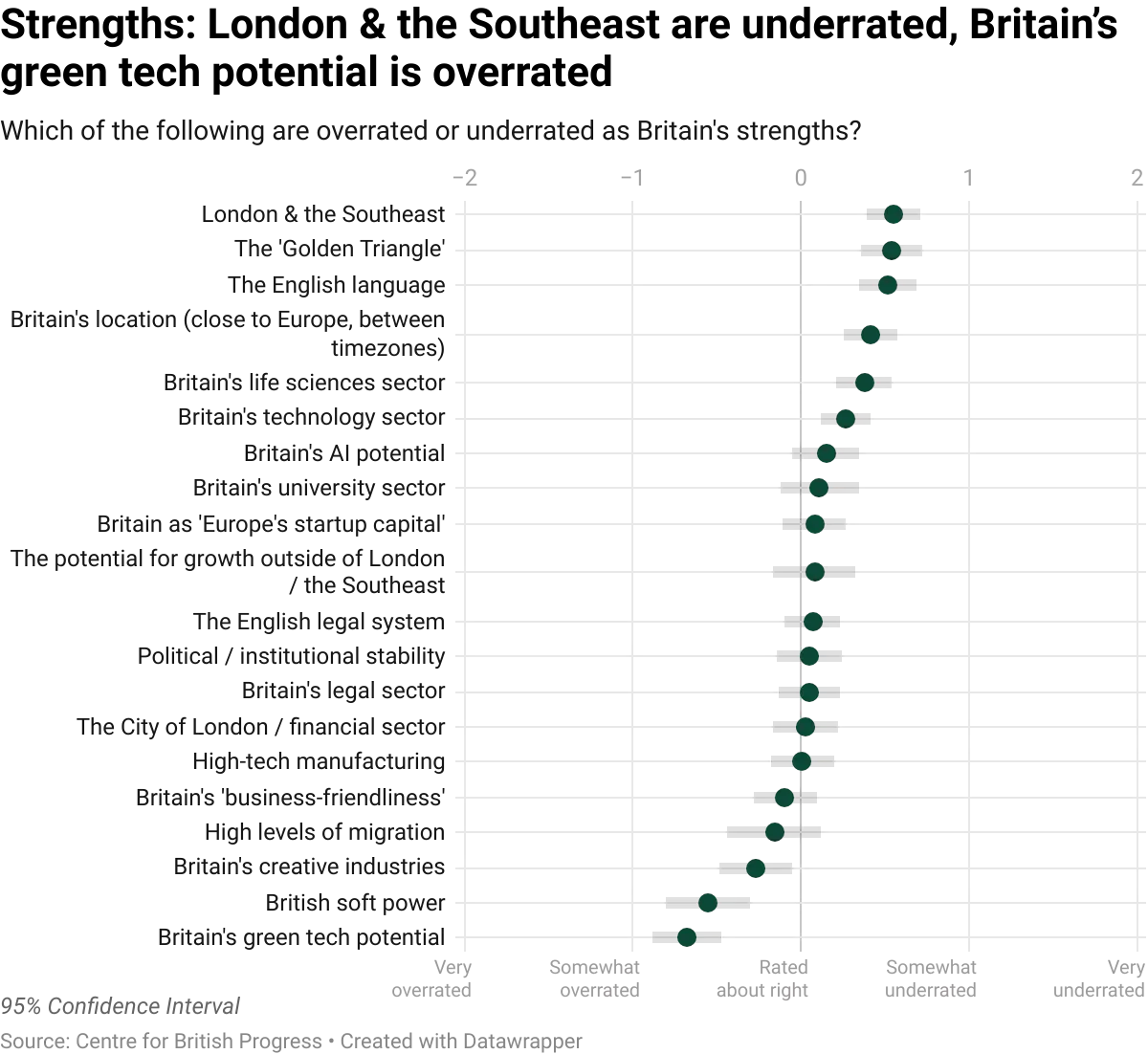

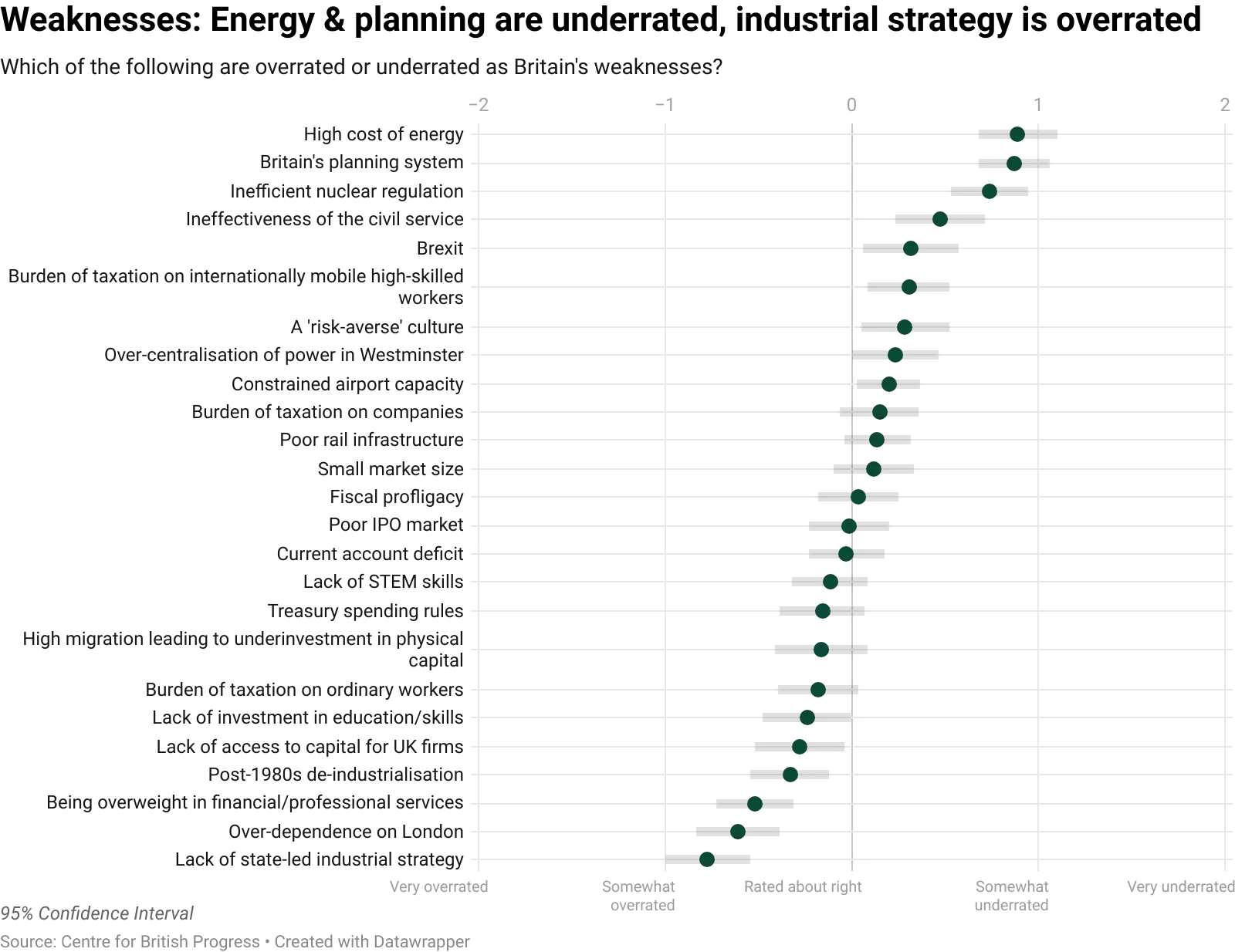

We asked responders to assess Britain’s economic strengths and weaknesses. We did this by asking which of Britain’s strengths and weaknesses are most “overrated” or “underrated”, relative to “most policymakers or pundits seem to think”. The aim is to get a clearer sense of where our responders differ from general received opinion.

On strengths, our responders thought that London & the Southeast, the English language, the ‘Golden Triangle’ (of London-Oxford-Cambridge) and Britain’s geographical location were particularly underrated. This means that they thought these factors are greater strengths than is commonly thought.

Meanwhile, responders generally thought that the economic benefits of Britain’s green technology potential, soft power and creative industries were typically overrated. They thought that factors like Britain’s university, legal sector and the City of London were rated about right (though there were disagreements about each of these).

When it comes to weaknesses, responders highlighted our planning system, energy costs, civil service ineffectiveness and Brexit as underrated as weaknesses. Indeed, the importance of state capacity was frequently highlighted in freeform responses. This means that they viewed these problems as even bigger than is typically thought.

Meanwhile, the average respondent was relatively sceptical of the view that Britain is overweight in financial and professional services, overdependent on London, or lacking state-led industrial strategy.

4. Specific policy areas

We wanted to get respondents’ thoughts on some specific policy options in planning, energy, AI and tax, given some of the choices facing the Government in the upcoming Budget and over the next year.

Housing & infrastructure

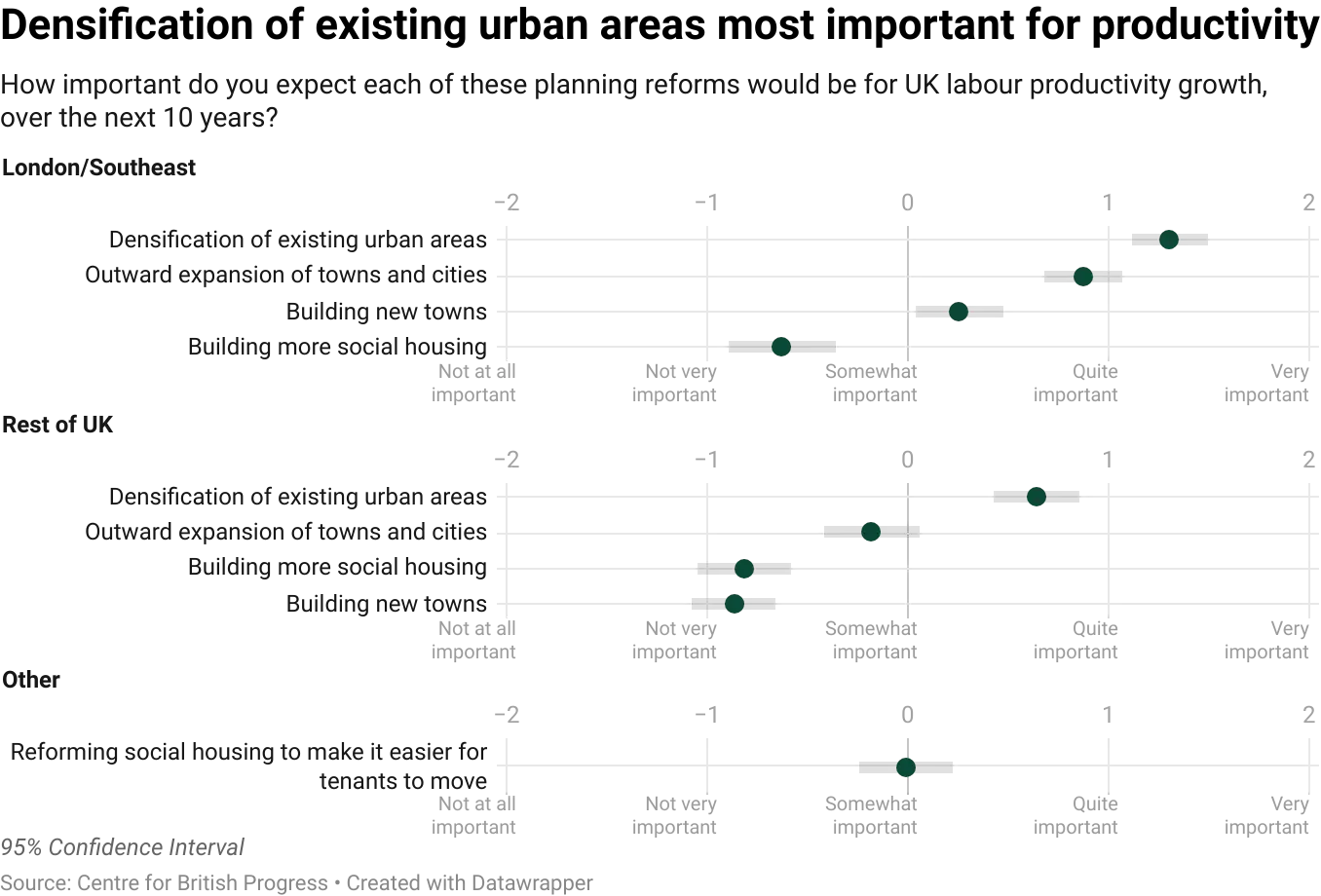

Given the clear prioritisation of building housing and infrastructure, we presented some more specific options for how and where planning reform takes place, and asked responders which are most important for productivity growth.

Responders generally preferred (1) improving density of urban areas, rather than building new towns, and (2) building homes in or near London, rather than in other parts of the UK, for productivity growth. As would be expected, this broadly tracks house price data – the needs are greatest in urban areas, particularly in London and the Southeast.

Energy

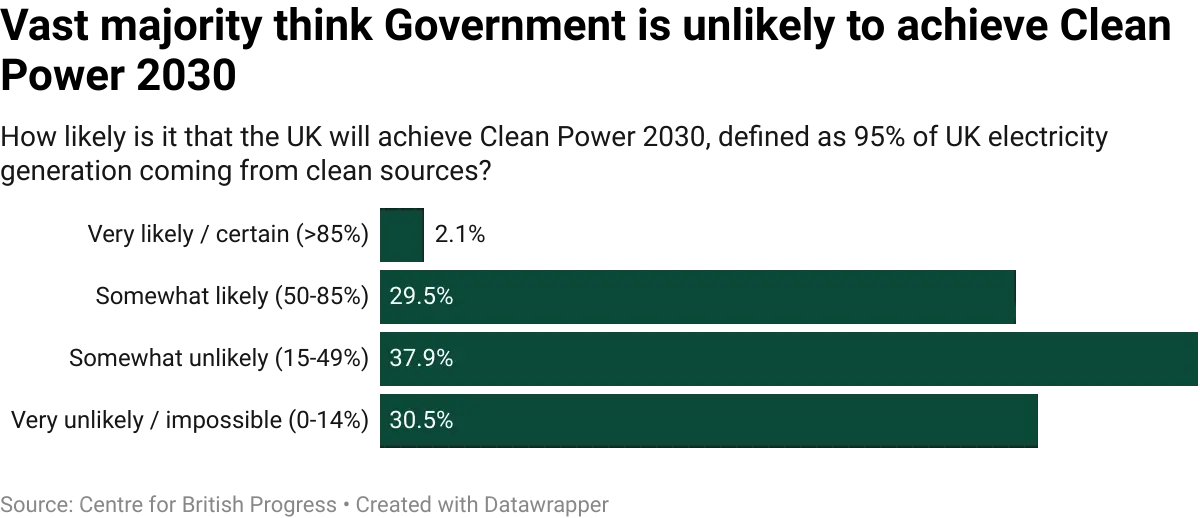

We asked responders several more specific questions on energy policy, including the likelihood of Britain achieving the Government’s goal of 95% of the UK electricity grid being powered by non-fossil fuel energy sources.

Responders were generally pessimistic about us hitting that goal – only 2% thought that it was very likely or certain, while 31% thought it was very unlikely or even impossible.

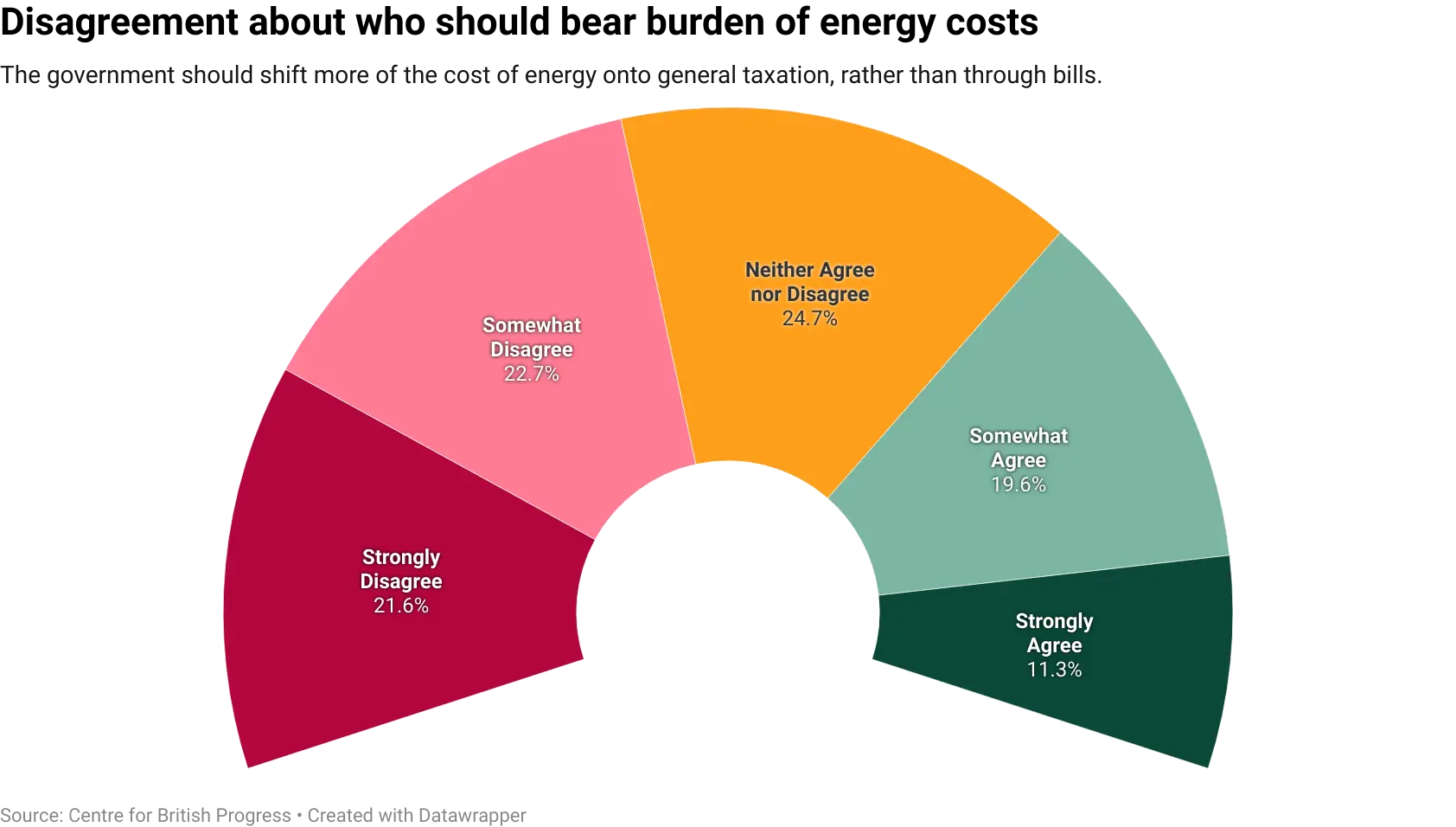

The average responder slightly disapproved of the idea of shifting some of energy bills onto general taxation, even though it was clarified that the aim would be to ensure that the government bodies that make energy allocation decisions are the ones who bear the financial cost of these decisions.

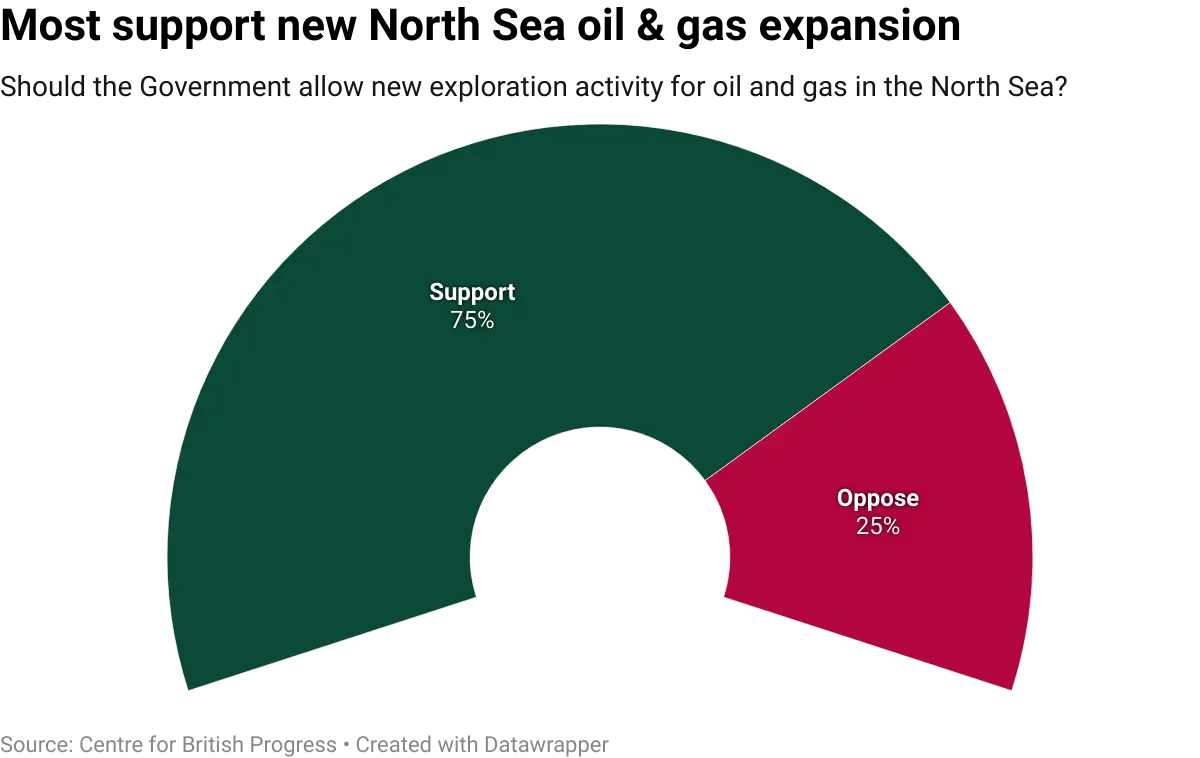

The majority of responders (75%) favoured allowing new oil and gas exploration in the North Sea.

In freeform answers, some responders also mentioned the importance of investing in grid and transmission infrastructure, the benefits of zonal pricing, ending “generous” Contracts-for-Difference (CfDs) for renewable energy sources, and using demand management technology to balance the grid.

Investment

We asked responders to identify the key barriers to business investment in the UK, which has declined over time, and is lower than many comparable economies. This could explain a large part of Britain’s poor productivity.

We distinguished between firms expanding activity to new sites and locations in the UK, and firms making additional investments in existing activities.

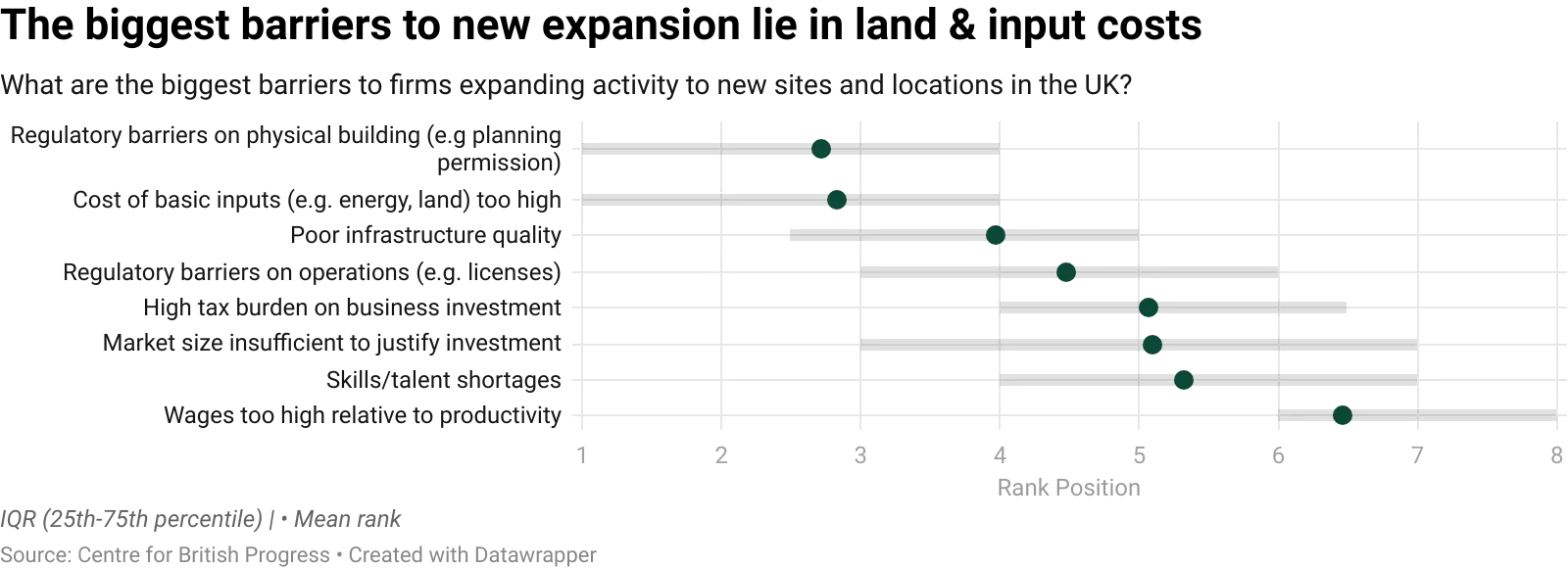

In both instances, responders ranked the cost of inputs such as energy and land (but not labour) as more significant than other factors, followed by regulatory barriers. Wages ranked lowest, meaning that responders did not think that wages are too high for investment compared to the other factors listed.

We also asked responders about the main barriers to technology adoption. Here there was less consistency, with responders disagreeing about whether the biggest barriers are regulation, cultural conservatism, access to capital, skills or other costs. Given that slow technology adoption is likely to be a key barrier to productivity improvements, and could become even more important with the arrival of AI, it will be important for the Government to identify which of these barriers are of highest priority.

AI

We asked responders to predict how AI will impact productivity over the next decade. Specifically, how much of the increase in productivity in the year 2030 will be attributable to improvements in AI.

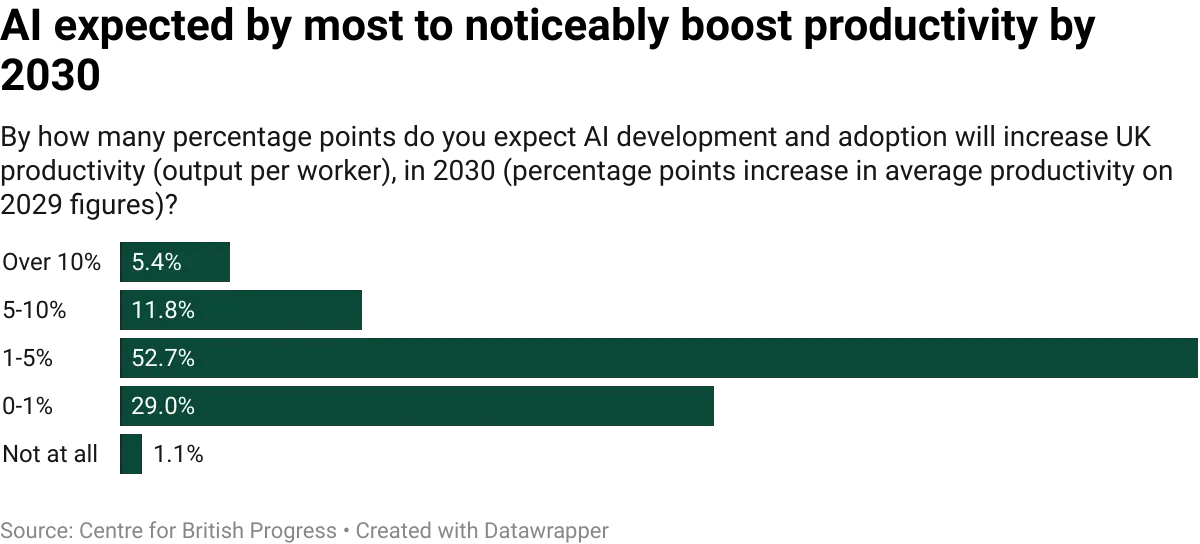

Most responders were optimistic about AI, believing it will have a positive impact, but the majority of these responders clustered towards the more modest end of the spectrum of 1-5 percentage points increase in productivity. That said, 5% is still a significant gain, and on reflection we ought to have distinguished further between different ranges. The fact that 5% of respondents believe that there will be a >10% increase in productivity in 2030, resulting from AI, is notable.

In written responses, several people highlighted that the benefits from AI lie more in adoption rather than in building new AI infrastructure. Though there was also significant support for attracting data centre investment, to support industry and create demand for next-generation nuclear technologies.

Conclusions

1. Build, Build, Build

The most obvious conclusion from our survey results is the overwhelming need to build both housing and infrastructure in Britain. This is seen as relatively costless – at least economically, if not politically – since the policy levers lie in planning reform and environmental regulations, rather than increased state spending. One respondent even went as far as to say that “spending is mostly irrelevant… We need to change institutions.”

In last year’s survey, we observed similar results. The Government went on to introduce the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, which aims to streamline many of our planning blockages. The Bill is particularly ambitious on streamlining processes for greenfield sites, and simplifies many of the environmental processes (though some of these have since been watered down in amendments to the Bill).

However, our results imply that the Government needs to go further and faster. The government could use its Parliamentary majority to fast-track projects of national importance, such as Heathrow expansion, Northern Powerhouse Rail, AI Growth Zones and the Oxford-Cambridge Growth Corridor.

The Government could also use a broad range of levers other than primary legislation to increase housing supply. We could fix the obstructions to housing (such as London Plan rules on ‘dual aspect’, limits on homes per floor, and the effective prohibition on building homes in the distant background of landmarks or near the Old Oak Common HS2 station). We could encourage tenant-led renewal of existing lower density estates, delivering better lives for the current residents along with homes. Similarly, we could make it far easier for people to extend their homes, build upwards, build a small ‘granny bungalow’ in their rear curtilage, or set a more ambitious plan for their own street. International examples show that this would substantially and rapidly improve delivery in areas with the highest housing demand.

2. A tale of two countries

A more detailed look at the responses reveals, broadly, a tale of two countries. London and the surrounding area enjoy strong agglomeration effects, broadly decent public transport and less reliance on energy supply for its services-based economy. However, they are severely constrained by a lack of affordable homes (and even better transport wouldn’t do any harm).

Meanwhile, many other parts of the country have far cheaper housing, but lack public transport connectivity, depend on ailing and congested roads, and are more sensitive to recent increases in energy cost, which hamper industry.

While London and the Southeast need radical planning reform to boost housing supply, other parts of the country would benefit from public spending and devolution. In theory, this is a good match of complementary needs: allowing more building and growth in London would generate significant revenue, which can be spent on new transport infrastructure and regeneration projects in towns and cities across the UK. And many parts of the country would benefit from stronger value capture powers for local governments to fund transport infrastructure.

3. Energy is underrated but also difficult

Several responders highlighted the crippling effect of electricity prices in the UK – among the highest in the world. This most obviously affects household bills, effectively reducing real incomes. But high electricity prices are particularly painful for energy-intensive industries, ranging from traditional heavy industries like steel, to the AI data centres of the future.

Our responders resoundingly agree that reducing energy cost is of paramount importance for this Government. The challenge is how. Some interventions are extremely worthwhile but will take time to materialise, such as relaxing regulations that make it incredibly expensive to build nuclear power stations. Several responders were optimistic about the potential from new Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), but even the most optimistic experts agree these will not be online before the end of the decade.

This pushes other responders towards fossil fuel options, and perhaps explains why there was general pessimism about the Clean Power 2030 goal, and overall support for new oil and gas exploration in the North Sea. However, while further exploration may offer a new source of tax revenue and some employment, it is unlikely to have much of an effect on energy prices, as the UK trades gas on a global market.

The Government is left with precious few levers at its disposal to reduce energy bills: they could effectively subsidise them (by removing VAT or carbon taxes), or they could reopen the locational pricing debate, having just closed it. In the medium term, they could offer less generous contracts for difference (CfDs) for wind power, whose price has not fallen as much as experts hoped at the start of the decade, meaning that households and taxpayers are paying more than expected for green energy. However, the benefits of reduced CfDs now would not be felt for another five years or so.

And so we arrive at the disappointing conclusion that, while the cost of energy is considered important for UK growth, there is little the Government can do about it in the short run. Of course, that should not stop it making the necessary regulatory and energy market reforms, as well as grid and transmission infrastructure investments, to radically improve the longer term.

4. Fiscal constraints are real, but not insurmountable

Our responders were clearsighted about the fiscal challenges facing this Government. Not one responder proposed radical increases in state spending, and indeed the vast majority thought that the most effective levers for growth lay elsewhere. As one responder said, “problems in the UK economy are predominantly not a consequence of underspending. Consensus exists around where to reduce spending; candidates for increased spending are more sparse.”

Furthermore, our responders were full of ideas for how the Government can raise revenue without hampering growth. This is good news for the Exchequer. However, economists’ favourite taxes are not necessarily the same as the public’s. Broadly speaking, our responders favoured increasing taxes on consumption, through taxes on alcohol, tobacco, gambling, driving (through fuel duty and vehicle excise duty) and flying (through air passenger duty), as well as removal of VAT exemptions.

Many respondents favoured replacing Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) with a proportional property tax, which is seen as less distortive, fairer, and delivers more consistent revenue for the Treasury. As one said: “with many taxes, the challenge is less around levels than design. Nowhere is this clearer than council tax, business rates and stamp duty - which should be abolished entirely and replaced with a property tax.” Similarly, several respondents mentioned removing the £100k income cliff-edge, described as a “broken incentive”, which encourages highly productive workers to reduce their hours or accept lower wages.

Our responders broadly (though not without exception) thought that reducing spending on welfare and social security, and state pensions could be good for growth (note that we did not ask responders, in this instance, to consider social or political consequences). The triple lock was an object of particular ire, described by one responder as “an extremely expensive giveaway to people who are, on average, reasonably well off.”

5. There are free lunches out there

Lastly, to end on a positive note, our responders broadly seemed to believe that there are many free (or at least, very cheap) lunches out there available to policymakers – they just need to know where to find them. By this, we mean interventions which carry little political or no cost for significant economic benefit.

One cheap lunch, raised by several responders, is in high-skilled immigration. This is politically far less controversial than increasing lower skilled migration or accepting refugees, but comes with significant economic dividends. One respondent identified a particular opportunities arising from the US’s recent hostility towards migrants: “the UK could generate some tactical wins from geopolitical shifts: attracting global talent displaced from the US for business/academia through visa reform and subsidies; and engaging US-based multinationals in (especially) advanced manufacturing and life sciences reevaluating their global supply chains on investment in UK's regional clusters.” Similarly, several respondents cited closer trade ties with the EU (but not reversing Brexit), as a relatively cost-free way of boosting growth.

When it comes to tax, the aforementioned £100k cliff-edge is seen as a cheap lunch– described by one responder as “the lowest hanging fruit in policy.” Others reiterated stamp duty reform and taxes on socially harmful consumption (such as gambling), though these would presumably carry more political risk.

A cross-cutting ‘free lunch’ lies in radically improving state capacity, which was frequently cited in individual written responses. This includes: decision-making capacity at the centre of Government, to speed up decisions and choose between competing priorities; regulatory capacity to fast-track infrastructure and respond more quickly to new technologies and industries; better technology adoption and data-sharing across Government; and delivery capacity in key areas – such as providing grid connections.

But the biggest wins – at the risk of repeating ourselves – lie in planning reform. Improving density in urban areas can, done correctly, be politically uncostly, free for the taxpayer, and a powerful driver of growth – each additional home in central London or York or Bristol allows an additional worker to move to a highly productive job. Devolving powers, particularly to allow local transport projects in Leeds or Sheffield, paid for by empowering mayoral authorities to raise their own funds, would be popular and boost growth. Expanding Heathrow, building the Oxford-Cambridge railway and fast-tracking data centers would stimulate private investment, generating jobs and a return for the Exchequer.

The UK’s planning system, and various associated regulations, means that the state is its own worst enemy: while the Government wants growth to be its “defining mission”, another part of the system is slowing things down. But this is a blessing in disguise: if Britain’s economy is held back by its own regulatory morass, rather than some fundamental aspect of its land or labour, there is nothing stopping us from fixing it. The ideas, ingenuity and productivity of the British people are waiting to be unleashed.

Methodology

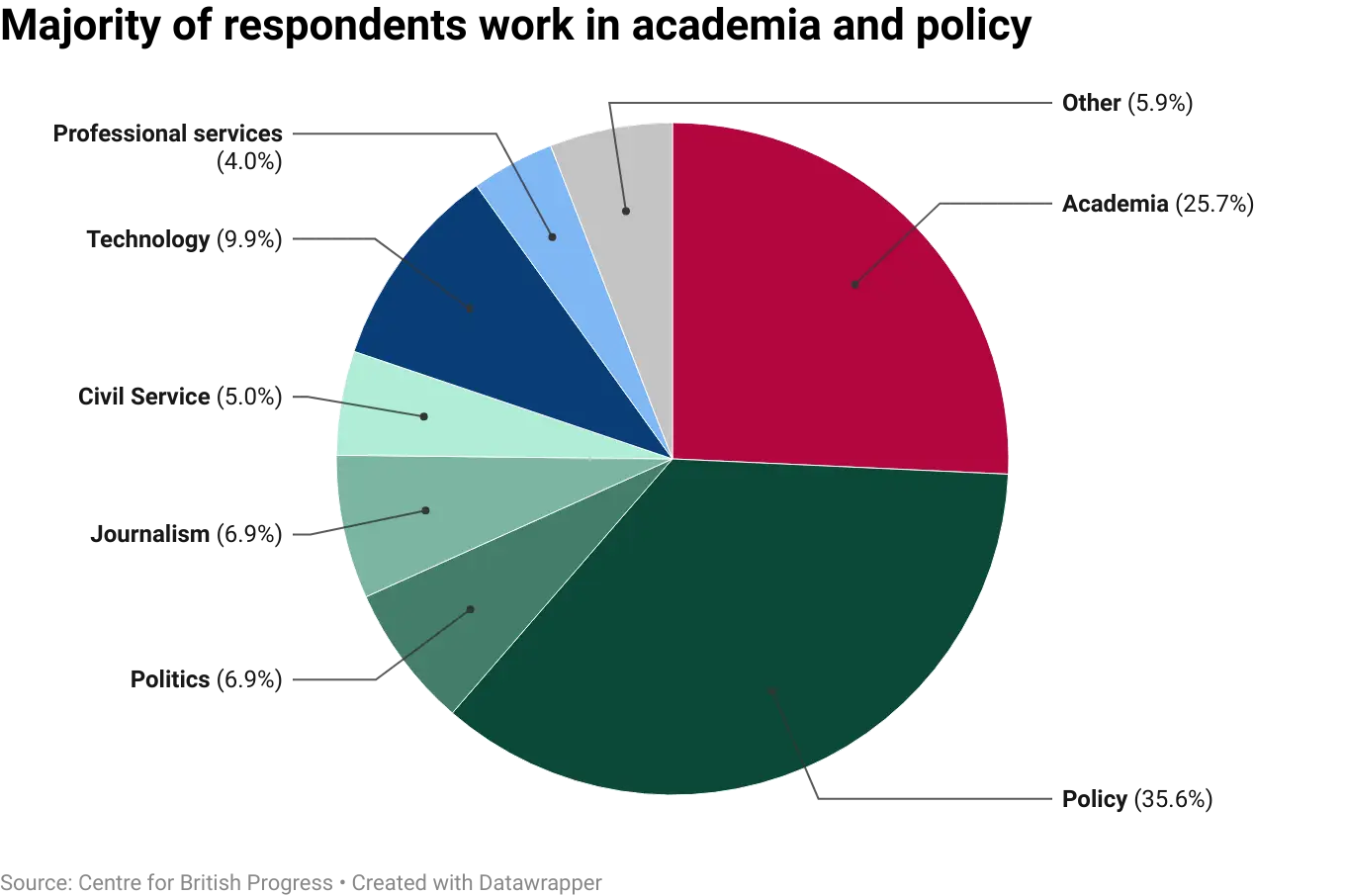

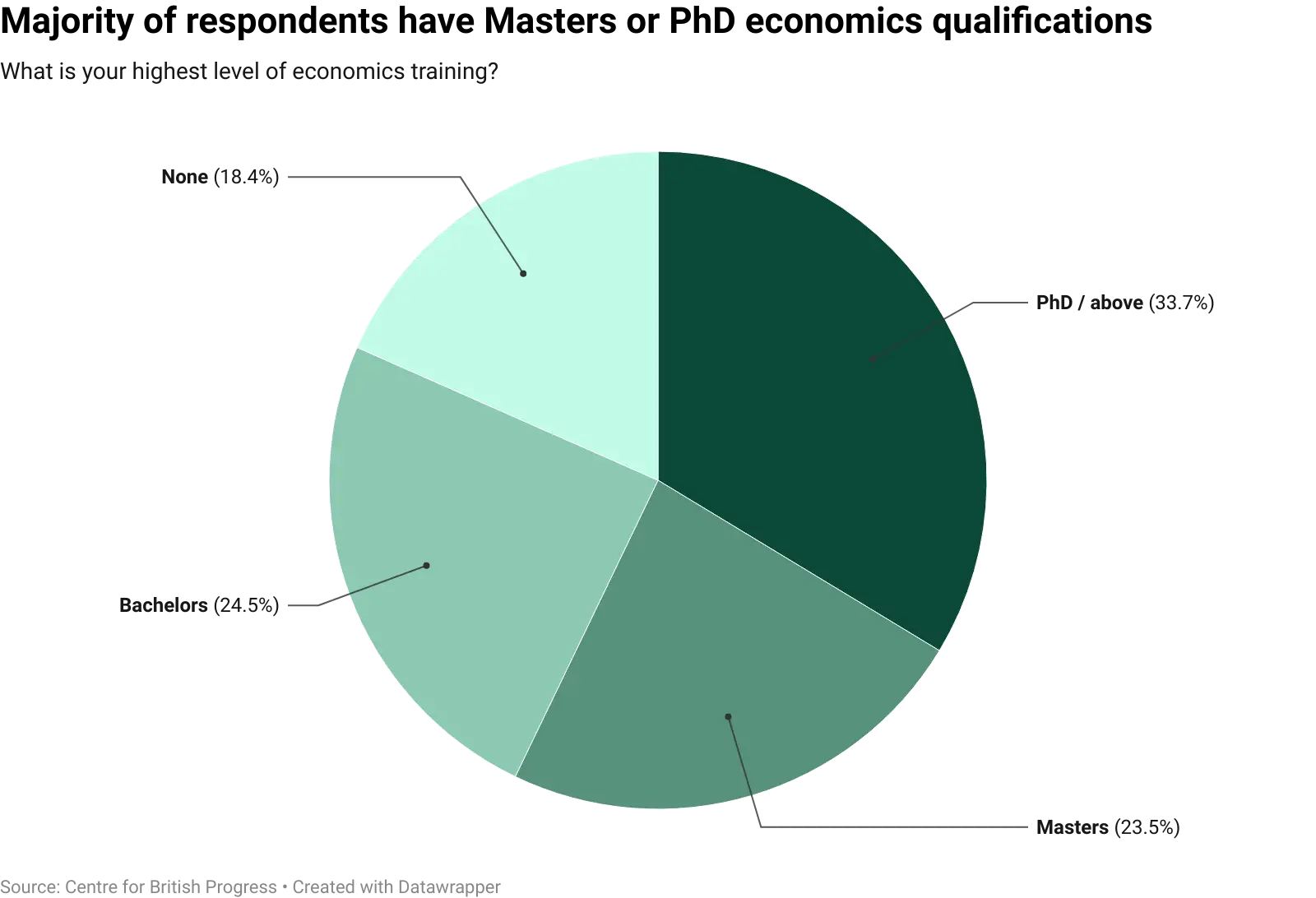

We sent the survey to 300 of Britain's leading economists and economic policy researchers, and a few experts outside the UK who have knowledge of Britain’s economy and policy system. We received over 100 responses. Over a quarter were from academics, and just under a third from think tank researchers. The rest included individuals in business (particularly finance and technology), journalists, civil servants and politicians. The vast majority had degree-level economics training, and around a third had PhDs in economics.

While we strove for fair geographical and gender representation, this proved difficult. A majority of responders were from London and the Southeast, with the rest spread reasonably evenly across other regions of the UK, with a handful of international responses. This broadly reflects the vast majority of think tank researchers and policymakers being in London. However, we could have done a better job of prioritising experts from other parts of the UK, and will try to do better next year. Similarly, we will aim for a more equal gender balance next year. In this survey, 76% of responders were male, and 24% female, which broadly tracks the ratio of males to females in the economics profession, but is nonetheless an imbalanced ratio.

The survey was conducted over the month of August 2025. If you want to know more about the methodology and how we selected responders, please feel free to email us at [email protected].

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]