Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Capital Markets and the Infrastructure Challenge

- 3. Forced Funding Misses the Problem

- 4. Authors

- 5. Acknowledgements

Summary

The UK's capital markets are not working. People’s savings are not being effectively channelled into productive, long-term businesses. This is reflected in declining IPOs, a shrinking number of listed companies, and difficulties faced by innovative firms seeking growth capital.

However, many proposed reforms to ISAs and pensions turn out to promise illusory benefits. Proposals to force domestic investment through ISAs or pension mandates misdiagnose the problem, and would harm savers by concentrating risk. Such policies fail to address the root causes of underinvestment in British equities.

This paper argues that Britain’s investment landscape faces two challenges. First, the UK financial system has structural flaws, including a highly fragmented pension sector, a collapse in critical equity research, and high transaction costs that hinder efficient investment. Second, and more fundamentally, the UK’s high-cost business environment makes many companies uncompetitive, and therefore unattractive investments.

We propose a two-part strategy: targeted reforms to improve the mechanics of the financial market, combined with supply-side reforms to lower business costs and improve the fundamental competitiveness of UK firms. Together, these can create a system where capital flows to competitive enterprises based on merit, not political direction.

Recommendations

- Reject Mandated Investment Schemes. The new government is right to abandon previous proposals for a ‘British ISA’, which would force savers to accept lower returns and higher risk, while channeling capital to firms for reasons other than commercial merit, leading to poor economic outcomes. For the same reasons, the government should not pursue UK equity quotas in pensions, a proposal which is based on the same flawed diagnosis.

- Encourage Pension Fund Consolidation. The UK’s fragmented pension system creates high costs and limits investment capacity. The government should encourage consolidation by creating a simpler regulatory process for individual DB-to-DC scheme transfers and by establishing DB Master Trusts. This will allow smaller schemes to pool assets, reduce administrative costs, and access a wider range of productive investments.

- Fix Critical Market Infrastructure. To help investors allocate capital efficiently, two issues must be addressed. First, the FCA should work to restore the economic basis for equity research on smaller companies by adjusting MiFID II rules. Second, the Government could improve market liquidity and lower costs for investors by reforming or abolishing Stamp Duty on share transactions.

Focus on Fundamental Business Competitiveness. Financial reforms alone are not enough. A primary barrier to investment is that UK firms are often uncompetitive due to high energy prices, restrictive planning laws, and poor infrastructure. A supply side agenda that systematically lowers these input costs – through planning reform, regulatory reform and building infrastructure – is the most effective way to create commercially viable companies that can attract investment.

Capital Markets and the Infrastructure Challenge

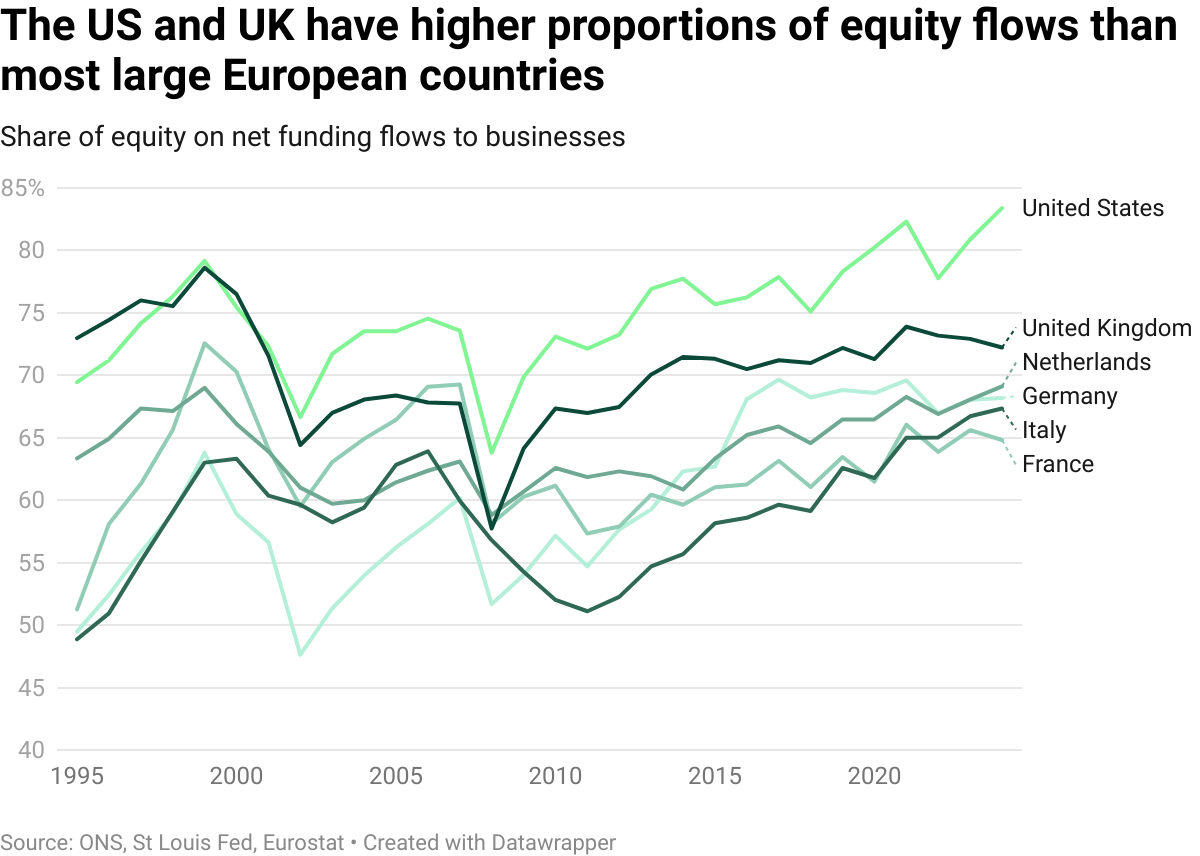

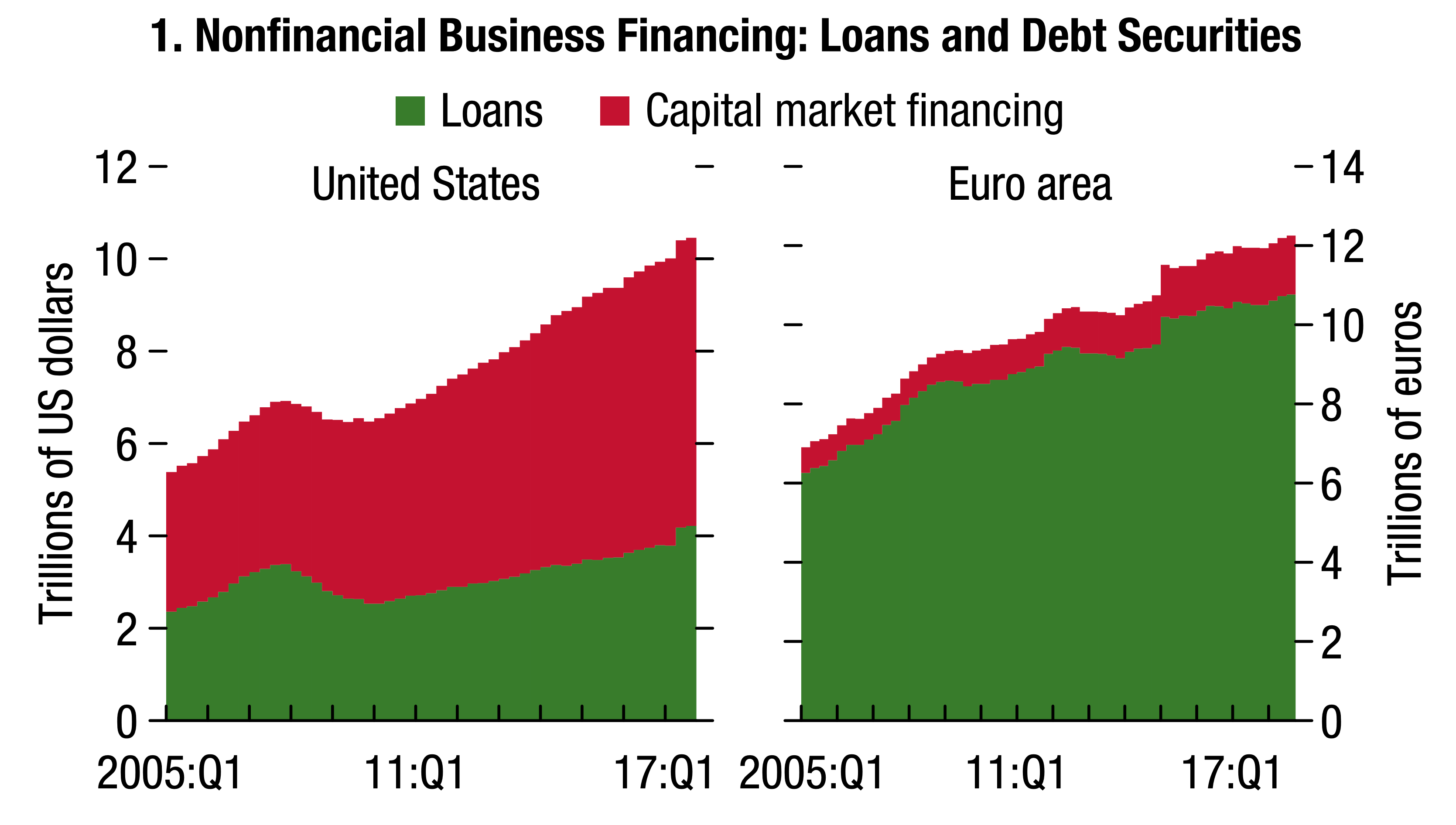

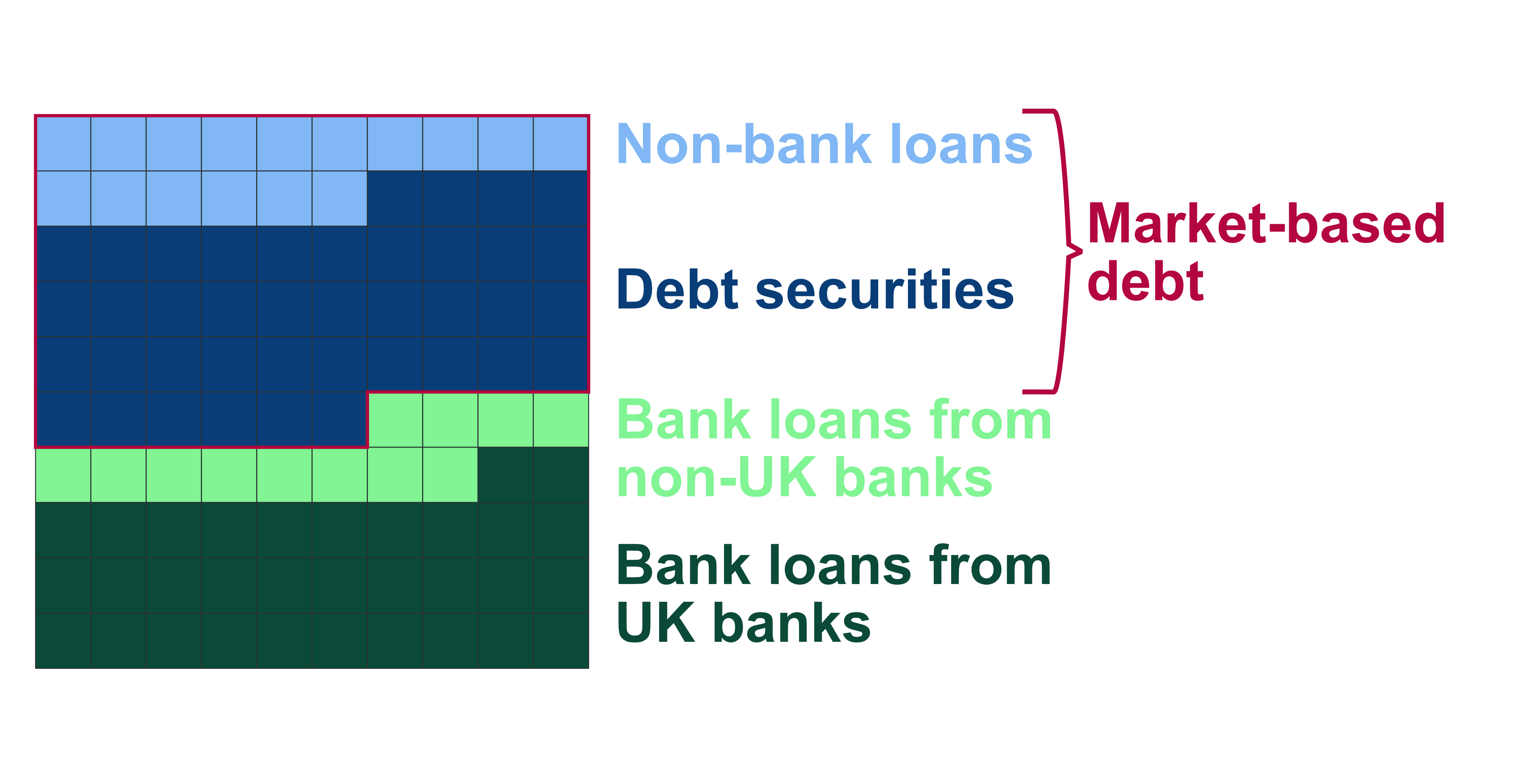

US companies raise a greater proportion of their capital through equities than European firms, which rely more on loans. British firms sit somewhere in between the two.

US financial markets have typically allocated more funding than their European counterparts

Funding of nonfinancial businesses

Funding of UK Businesses

The UK market is between both blocks

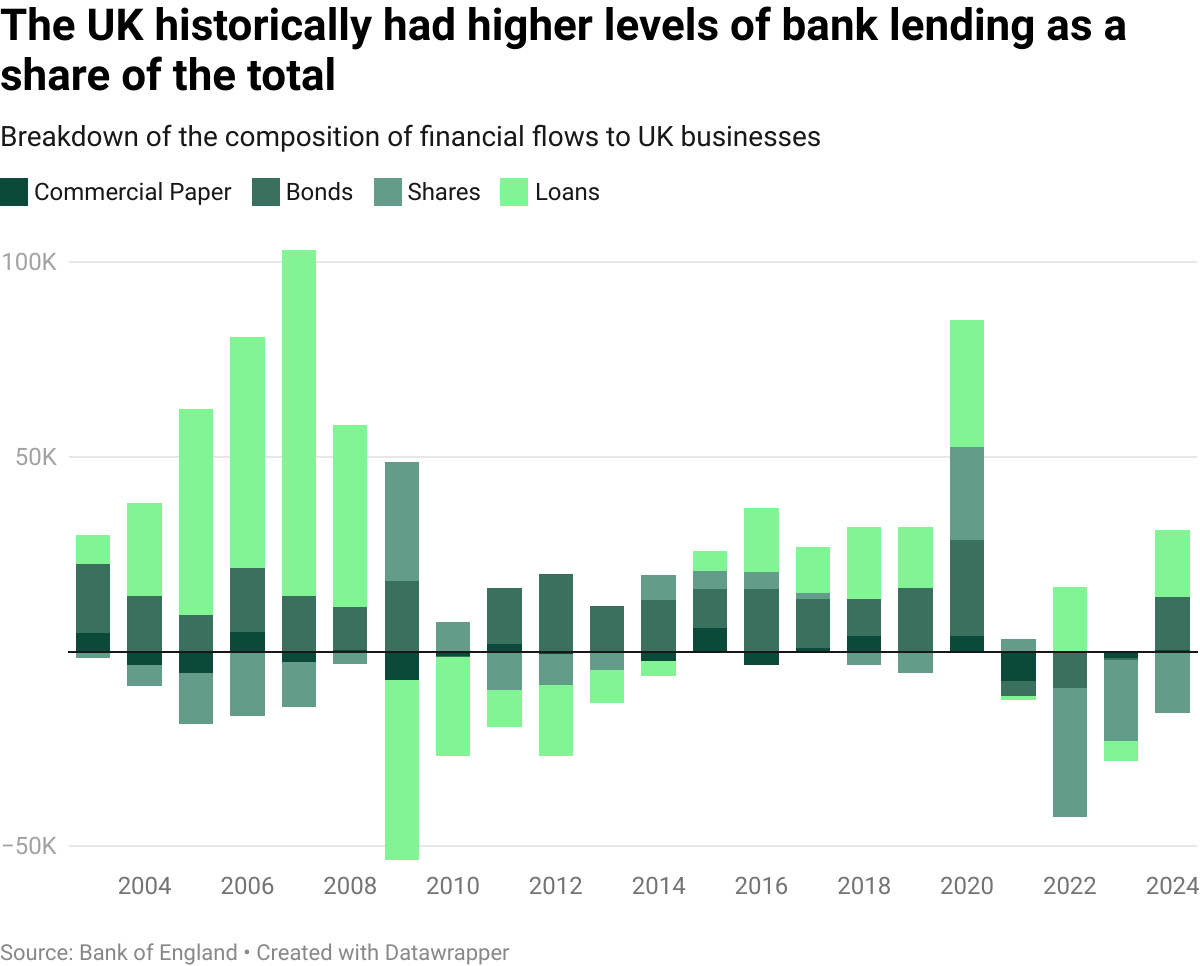

Data on net financial flows broadly supports this view, though lending has decreased as a source of net funding in recent years, while bond issuance has increased.

Much like the US market, the UK has also experienced a substantial reduction in the contribution of equity financing to net funding. While gross flows are hard to track, the relative importance of equity as a funding source has declined in recent decades. This is shown by the share of the total stock of equity relative to the sum of the stock of equity, bonds, and loans. This contrasts with the US, where the weight of equity in the overall stock has increased, even as the US has experienced negative equity flows due to buybacks and other redemptions.

This financing structure disproportionately benefits companies that fit traditional banking assessment criteria, such as those with collateral, predictable cashflows, and standardised risk profiles. Meanwhile, firms that require patient capital and project-specific evaluation lose out, as they tend to be a better fit for direct finance. Even as external finance has become more important in several mature markets, equities have been in retreat, in both the US and the UK.

According to Neil Woodford, the declining importance of equity finance and its associated problems are the result of past regulatory interventions. This suggests an important warning: well-intentioned but misguided interventions can have lasting counter-productive impacts, particularly when they introduce a benefit for small, vocal groups.

Across every dimension of market activity, the picture is one of decline. IPO activity has collapsed: the London Stock Exchange made up 18% of global activity by value in 2006, with a total of $45bn, but in 2023 recorded a total amount of under $1bn. The number of listed companies has contracted by 44% between 2008-2019, while follow-on capital raising has become anaemic, totalling just £18.8bn in 2023 (compared to £90bn returned through ordinary dividends and £57.4bn through share buybacks). Meanwhile, domestic institutional support has evaporated: pension fund ownership of UK equities has fallen from 32.4% of the market in 1992 to approximately 1.5% today.

These trends make it harder for companies to raise capital on listed equity markets. As listed equity financing has become less viable, companies have in turn become increasingly reliant on other funding mechanisms - primarily banking relationships and debt markets - that employ different assessment criteria and risk evaluation processes. This shift reinforces the dominance of collateral-based and covenant-heavy financing structures, which in turn favours established businesses with predictable cash flows, over innovative enterprises that require patient, project-specific capital.

These trends must be understood alongside the broader under-performance of UK equities. As documented in an excellent piece by Archie Hall, UK-domiciled equities have underperformed a 'World ex-UK' benchmark by approximately two-thirds over the past decade. This stark empirical reality compounds the structural challenges identified in Woodford’s piece, as well as the greater historical reliance on bank lending relative to US financial markets. The performance gap provides context for understanding the scale of dysfunction across UK capital markets beyond the specific mechanisms and institutional failures that have undermined equity financing.

Two Distinct Problems

There are two distinct but related reasons for the relative decline of (a) the UK’s financial market and (b) equities in general.

First: Equity Distortions

Even though direct financing has increased its share of total funding to non-financial corporations, this is in large part due to a rise in corporate debt instruments, rather than equity. This recent uptick should be understood in the context of financial intermediaries maintaining their central role in capital allocation. These institutions continue to perform the essential dual function of ensuring businesses can access capital whilst enabling savers to participate in higher-risk investments, but the mechanisms they employ - relying on collateral, covenants, and standardised screening - remain dominant even as corporate debt has grown alongside a significant decline in equity financing.

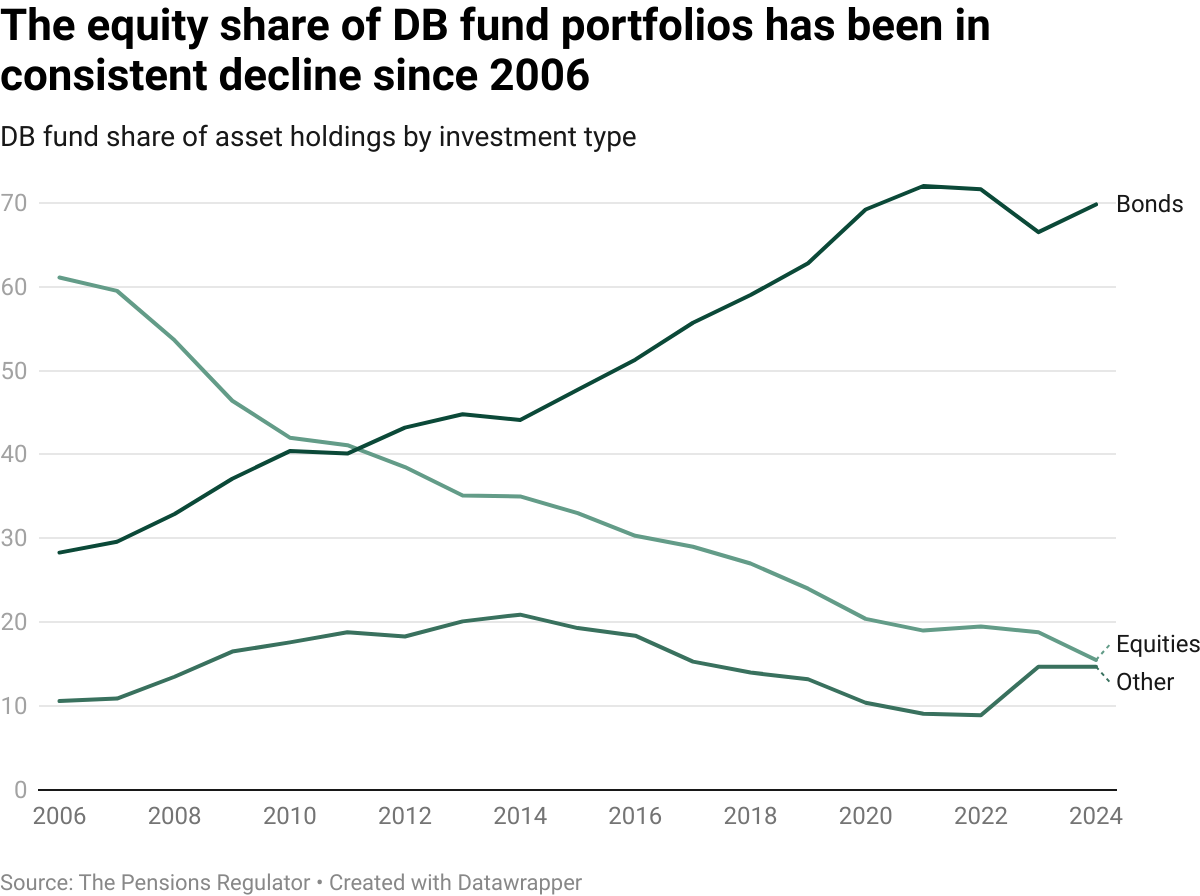

Woodford argues that a few regulatory changes have contributed to this process: FRS 17 accounting changes forced pension funds to de-risk from equities into bonds, and MiFID 2 destroyed the research ecosystem supporting smaller companies. The broader data suggests that the UK has seen a decline in equity’s share of gross funding flows in recent decades.

The mechanisms for allocating funding matter because they reinforce assessment criteria that favour established businesses with collateral and predictable cash flows over innovative enterprises that require patient investment. This is true of bank lending and debt instruments, to a lesser extent of private equity, and even less so for venture capital. For a range of companies at different growth stages, equity is often a more appropriate source of finance, and the gradual erosion of this market means those companies will find it harder to scale. On the other hand, simply reversing these regulatory changes would likely be counterproductive because they helped reduce the degree of moral hazard associated with higher-risk investments.

Second: Constraints on Fundamentals

While equity financing gaps are a barrier for many deserving companies, it is important not to conflate this issue with investors believing UK-domiciled companies to be unattractive investment propositions, at all growth stages. As noted both by Hall and Woodford, the UK stock market has significantly underperformed a number of relevant comparators over several decades, which is reflected in relatively cheap equities relative to their earnings potential.

This underperformance isn’t restricted to listed companies. Analysis by Damian, an inventor of patents in traffic management and vehicle tech, suggests that UK DeepTech unicorns generate average revenue below £100m despite billion pound valuations, with the highest performer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) reporting revenue of only £170m in 2023 (below their 2022 value). Many companies with billion-dollar valuations generate revenues well below £50m, suggesting a substantial disconnect between market valuation and demonstrated commercial performance.

But underperformance is not universal. Companies with lighter operational footprints and clearer pathways to profitability have found it relatively easy to scale and find financing along the way.

It is plausible that UK fintech unicorns like Revolut (£3.1bn revenue), Starling Bank (£714.4 m), and Monzo (£880m) could access capital more easily because they resemble traditional banking assets – with predictable transaction revenues, clear cash flows, and regulatory frameworks – which make them appealing prospects to lenders using conventional risk assessments.

These companies also benefit from agglomeration effects in financial services that can outweigh input cost disadvantages, while companies with a heavier footprint in terms of physical infrastructure and equipment, or greater energy needs, face considerably more challenging constraints on what they can build, as well as more punitive mark-ups on input costs. It is no surprise that 15 out of 50 companies in Beauhurst’s list of 50 UK unicorns, and 4 of the 5 most valuable, could be described as being in the fintech sector. The relative success of this sector tells us that when investors can identify the relevant commercial pathways towards profitability, funding is available.

This suggests that financing constraints are not the primary bottleneck for viable UK companies. Instead, the challenge lies in helping companies develop clear, credible pathways to profitability that investors can identify and believe in. Companies requiring significant infrastructure investment – such as many DeepTech companies – face a double disadvantage in Britain: they need patient capital for development while operating in a high-cost environment that undermines their position relative to international competitors. The UK's high energy costs, expensive industrial land, complex planning regime, and inadequate infrastructure create structural disadvantages that make many capital-intensive enterprises commercially unviable, regardless of funding availability.

Policy Implications

The preceding discussion suggests that there are two avenues for action: first, make equities more appealing, to cater to companies that would benefit from this type of financing. Second, address the supply side constraints on UK companies which make them less viable prospects. These routes would be more promising than forcing money into UK equities.

Forced Funding Misses the Problem

Proposals to channel more domestic capital toward UK companies, such as the British ISA or UK equity requirements for pensions, are well-intentioned but fundamentally misdiagnose the problem. They focus on the symptoms of capital market inefficiency rather than the root causes. The scale of the implied market failure – that UK markets are so broken that only coerced retail investment can fix them – is implausible in a sophisticated G7 economy. This approach treats a symptom with a tool that ignores the underlying disease, risking significant harm for no discernible benefit.

The Problem with Forced Capital Allocation

Any policy that forces capital allocation, regardless of the specific mechanism, suffers from a set of predictable and damaging flaws. These range from practical definitional issues to severe, negative economic consequences for both savers and the market itself.

Is there a “UK Equity” in the room with us?

For starters, it is not even clear what is meant by a "UK equity." Index-provider rules from FTSE and MSCI rely primarily on legal domicile and primary listing, and to a much lesser extent the company's actual operational footprint to determine whether a company can be classified as a “UK company”. With approximately 80% of FTSE 100 sales and 55% of FTSE 250 sales originating abroad, it is fair to assume that many companies listed in the UK are, at most, only partially based here. Most of their activity takes place abroad, and their economic footprint varies considerably; some have a large impact on domestic value added and employment, while others much less so. Defining a “UK equity” in these terms would largely encompass multinational corporations with significant activity abroad; we should expect these firms to be able to raise capital from foreign investors. These companies are likely to face few barriers to accessing finance, given their international footprint and diversified shareholder structure. The result is that we could forcibly allocate funding to companies with no meaningful impact on UK economic activity.

We could, instead, allocate capital to those businesses that are majority-owned by British residents. This would ensure at least some link to the domestic economy and prevent funds from flowing abroad to finance activity outside the country. But this is obviously problematic; not only is the ownership structure of most businesses very difficult to pin down, but a narrow definition would necessarily exclude a large number of flagship UK companies that would not meet this test, such as AstraZeneca or Unilever. In practice, it would force a substantial amount of savings onto a very shallow investment pool which, depending on the policy and vehicle, either make tax-advantaged savings accounts undesirable or put pension funds at serious risk. Either way, it is hard to imagine how such a narrow definition survives contact with the real-world.

The FTSE and MSCI indexes do use other metrics to define a company based on its economic footprint, but none of these approaches resolve the fundamental trade-off. If the definition remains equivalent to 'listed on UK exchanges', then the problems with economic footprint persist - most capital would flow to multinationals with minimal domestic impact. If the definition becomes more restrictive to capture genuine UK economic activity, then many currently listed companies would become ineligible, creating an administratively complex system that forces investment into an artificially narrow and potentially illiquid pool of assets. If we cannot sensibly define a UK equity, we should not pursue a policy that depends on this definition.

Access to finance isn’t the problem

The premise of proposals like the British ISA is that UK companies are starved of capital, and that if they had more of it, they would deliver high growth and returns. Because investors will not overcome their reluctance to invest in “UK equities”, the state should step in and mandate it (or at least encourage it through tax incentives).

Proponents might protest that one of the central goals of the policy would be to increase funding to newer companies wanting to scale up, rather than established, listed companies. They might argue that we should not be too quick to dismiss UK equities based on low returns, because early stage companies can have low returns while being excellent investment prospects. While this is certainly true, the reverse inference is also mistaken: the fact that some companies grew after receiving funding for a long time does not mean that the availability of funding was the cause of that growth. Many companies are not investable propositions regardless of how much money is thrown at them, and there are many unobservable factors that investors look to as indicators of future success that are not easily observed from the outside. Taking the proposition that funding is the necessary precondition for success to its logical end would lead to the obviously absurd conclusion that any potential investment could succeed if only it received the right levels of funding.

We can go even further: the very fact that both companies with strong revenue performance and those that don’t yet have strong financial fundamentals can secure funding is evidence that investors do look at some of those factors that are not easily observable, and have at least some capacity to identify potentially viable opportunities. What these facts do not tell us is whether the amount of capital flowing to these companies is socially desirable, precisely because there are no clearly observable metrics on which we could make that judgement.

We can consider a few examples from the analysis of a few relevant UK unicorns and rough estimates of their current levels of revenue. Despite relatively limited revenue streams, many of the companies in this list have had valuations exceeding £1bn, based on their most recent funding rounds. At a minimum, this suggests that at least some companies can attract funding at appreciable multiples of their current revenue. Moreover, the apparent ability of these companies to attract funding at high revenue multiples may itself reflect the opacity of private markets, where infrequent valuations and structural incentives can sustain inflated assessments longer than daily mark-to-market pricing would permit.

Company | Revenue (£m) | Sector |

|---|---|---|

Oxford Nanopore Technologies | <200 | Genomics/Sequencing |

Flo Health | <200 | Health Tech |

Inspired | ~100 | Energy Systems |

Matillion | ~100 | Data Analytics |

Improbable | <100 | Gaming/Simulation |

Lighthouse | <100 | Analytics |

Motorway | <100 | Automotive |

Quantexa | <100 | Decision Intelligence |

Spectrum Medical | <100 | Medical Devices |

Synthesia | <100 | AI Video |

Wayve | <100 | Autonomous Vehicles |

Multiverse | <100 | EdTech |

Zilch | <100 | FinTech |

Beamery | <50 | HR Tech |

CMR Surgical | <50 | Surgical Robotics |

Tractable | <50 | AI Insurance |

Touchlight | <50 | Biotech |

But we can take this further still. While it isn’t yet clear whether many of these companies will eventually succeed, there are several examples of recently established online banks that have begun to deliver significant levels of revenue and profitability. These companies were funded through significant periods of low to little revenue, and investors ensured they saw through that stage of their growth to by providing sufficient funding, including through a global pandemic.

Good companies raise capital, but that does not imply that capital creates good companies. It would be an error to infer from the above examples that mechanically allocating greater funding to UK startups generically would have the same impact: that gets causation precisely backwards. Famously, Amazon survived for a long time until it finally reached profitability. Cases like that, and of companies like Monzo or Revolut, are not evidence that “if you fund them, they will grow”; rather, they are evidence that investors are more than willing to make long-term investments if they believe the fundamentals of a business. Reversing that logic to compel investment in companies investors do not believe in risks further undermining an already fragile ecosystem by keeping afloat companies that are unlikely to ever succeed.

Only about 5% of the companies in CBI’s Industrial Trends Survey said that raising external finance was one of the biggest factors limiting their capital investment. The two most common answers, uncertainty of demand and inadequate return, are instructive as to what companies feel the biggest problems are: they know more about the cost structure than about potential demand for a given price, and are not sure they can reach profitability. If some companies in the wider UK ecosystem can secure funding, and a smaller number still succeed, while most manufacturers indicate they don’t believe access to external finance is the primary challenge they face, there is good reason to think the diagnosis is simply wrong.

Not only are some companies attracting investment (which establishes this is possible), the very successful ones are very effective at doing so (which establishes some can succeed). In order for this problem to have the scale it is purported to have, we would need to believe that the UK’s financial market, which is widely regarded as one of the most sophisticated in the world, is incapable of performing one of its key functions, and further incapable of enabling international investors to take their pick from the UK’s most promising companies. The scale of misallocation would need to be so large it would be a surprise that the market functions at all.

Economic Impacts

Any forced allocation policy would create an artificial demand shock by forcing the adjustment of portfolios towards “UK equities”, resulting in asset price distortions that inflate prices beyond their fundamental values or investors’ current assessment of the appropriate valuation of companies. This has two negative effects.

First, if we define UK equities broadly enough, they can include companies that are not majority owned by UK residents, the intervention will create a perverse wealth transfer. Price increases will primarily benefit existing shareholders (which are mostly foreign) at the direct expense of UK investors who will either be compelled or incentivised to buy at artificially high prices. Furthermore, if international investors anticipate these distortions, they may respond by reducing their UK holdings, potentially leaving overall financing levels unchanged whilst simply transferring ownership from foreign to domestic investors at inflated prices. If we define UK equities more narrowly to exclude large multinationals domiciled or listed in the UK, this considerably shrinks the pool of eligible investments, significantly reducing risk-adjusted returns for retail investors or pension holders, depending on what precise mechanism is chosen.

Second, it causes capital misallocation. Whatever the definition of UK equity that is settled on, and which will inevitably be extremely politically charged, funding is re-allocated towards UK-based companies in some form. This will, if successful, shift the demand schedule for eligible domestic assets at every level of risk-adjusted return. Some worthwhile companies that might not have been funded otherwise will find it easier to secure external funding, but also many companies that could only secure funding at lower valuations will now be more likely to survive. Forcing the flow of funding doesn’t mechanically improve the quality of allocations within the relevant asset class, so this tide will lift most boats - including the ones with significant holes in their hulls.

If investors have any ability to identify at least some potentially viable companies in the current UK ecosystem, then distorting allocations through an implicit funding subsidy will worsen risk-adjusted returns by propping up economically unviable companies in the UK. In order for this not to be true, we would need investors to be completely unable to identify promising companies; as argued in the previous section, this is very unlikely. Diverting funds from more productive investments elsewhere props up economically unviable companies, and hinders long-term economic dynamism.

ISA-Based Interventions: Corrupting a Tool for Savers

The Individual Savings Account (ISA) has become an important feature of personal financial planning in the UK due to its simplicity and flexibility. Its primary role is as an efficient vehicle for individuals to pursue their own financial goals, whether that involves short-term savings in a Cash ISA (e.g. for a house deposit) or long-term, diversified investments in a Stocks & Shares ISA. Deposits of up to £20,000 per year can be made without being subject to income or capital gains taxes.

Recent proposals, however, have sought to repurpose the ISA from a tool designed to serve individuals savers welfare into a tool of industrial policy. This approach to policymaking always carries some risk, as it becomes unclear how to balance between different goals when they are in conflict.

Using ISAs to pursue industrial objectives is risky and could harm savers. Two main approaches have been proposed: "soft" incentives and "hard" mandates.

"Soft" Incentives: The British ISA Model

The "British ISA" was proposed by former Chancellor Jeremy Hunt in the Spring Budget 2024, before the proposal was formally scrapped later that year by the new Labour government. The British ISA would have offered investors an additional £5,000 tax-free allowance on top of the existing £20,000, but only for investments in UK equities.

This proposal suffered from many of the problems we have already discussed: it is difficult to define what makes an equity “British”, without undermining the presumed goals of the British ISA policy.

But the British ISA also posed considerable risk to individuals. By creating a specific tax break for a narrow asset class, such a scheme could subtly encourage less sophisticated investors to voluntarily over-concentrate in UK assets beyond what is optimal for their risk profile. They might do so purely to take advantage of the tax incentive, without fully understanding the significant concentration risk they were assuming. As Archie Hall explains , this exaggerates an existing downside risk, since investors are typically over-exposed to equities in their own country, and these concentrated portfolios tend to underperform a diversified one.

Finally, the reasoning for the policy was unsound.. It assumed that an extra £5,000 of tax-incentivised retail investment was a key missing ingredient for UK corporate funding; but the small scale of this capital is dwarfed by institutional capital. Furthermore, the majority of savers do not use their full, existing £20,000 allowance, which makes an additional £5,000 meaningless to most. As discussed earlier, access to finance is not the main problem when it comes to UK equity markets, so it is hard to imagine that the British ISA would register any meaningful impact – the only effect would be to distort the portfolios of British savers and potentially cause them to underperform.

"Hard" Mandates: Mandated ISA investments

A more aggressive proposal would be to mandate that a significant portion of the £20,000 ISA allowance is allocated to UK equities (for instance, up to half of the total). Such a measure would represent a far more direct attempt to increase the share of UK equities held by domestic residents. At first glance, this mechanism is simply a more expansive version of the “soft” approach outlined in the previous section. Most of the same caveats and issues would remain, from how one might even define these assets to the portfolio costs of strengthening home bias by fiat except, potentially, for the possibility that a significant share of the £725.9bn of total value of ISA holdings might flow towards British companies.

Under this policy, even if a large fraction of savers chose to reduce their contributions or stop using ISAs, it is still likely that a very considerable share of national ISA savings would be redirected towards UK equities. This warrants examining the particular mechanism in more detail. Why would we think that forcing people to invest in projects they do not believe will deliver sufficient returns, therefore requiring investors to accept lower yields to make funding cheaper for companies, could result in improved performance?

There are circumstances in which this might be true. Imagine that the UK has a large pool of high-quality potential investments that no sophisticated analyst could distinguish from completely worthless ones, such that investing in all of them would still deliver positive returns. In this world, good projects would face an excessive cost of capital and demand less capital for investment, which would cause higher-quality investments to be gradually removed from the market, with only worse ones remaining. This is the classic problem of the “market for lemons”, an instance of adverse selection;. Forcing investment, which would make a lot of supply chase relatively smaller demand, would push up valuations, reduce the cost of capital, and result in more investment in good companies. These would then deliver better returns, and everyone would be better off.

As is clear to anyone with the most fleeting interest in finance, this story rests on several strong assumptions. It must be the case that (1) high-quality investments exist in sufficiently large numbers, and (2) no amount of existing information held by relevant intermediaries, either through lack of information or incompetence, can be efficiently used to select better investment propositions. If neither of these hold, then some fraction of the forced savings are likely to be directed towards low-quality investments, keeping unviable companies afloat for longer.

But there is another argument for forcing investment. Asset prices can be driven not just by fundamentals but also by beliefs. Financial markets in particular are far from being perfect, and are prone to all kinds of manias and panics. If you can convince the market your investment really is high-quality, investors will line up to give you cheap enough capital that you can turn it into a high-quality project. Repeat this at scale, and the theory is that we could single-handedly jump-start the UK’s equity market:all it needs is a big enough shove, and its own momentum will keep it moving.

If this sounds too good to be true, it’s because it is. We can observe deviations from fundamentals for some significant periods of time, and there are examples of where a company hanging on for just that little bit longer was all it took for it to secure future success. But these instances do not imply that belief-driven investment can be repeated at scale and permanently adjust the course of entire asset classes. If this were the case, governments would only need to inflate the value of some assets for long enough and momentum would permanently increase their value. This is clearly ridiculous.

But what about reflexivity, momentum, or Keynesian beauty contests? These are all theories of why asset values can deviate from fundamentals for long enough to generate cycles. Once momentum builds up on the valuations of a particular asset or asset class, investors may be persuaded that underlying fundamentals are better than could be observed, and adjust their expectations accordingly. This fuels a positive feedback loop where higher valuations trigger higher expectations; that describes an asset price bubble: asset valuations exceed their fundamental value.

Bubbles, by definition, burst. However, they can persist for extended periods (potentially a decade or more) during which systematic valuation differences between markets can create self-reinforcing dynamics that affect real economic outcomes, such as acquisition patterns that shift ownership and potentially economic activity between jurisdictions. As valuations reach excessive values and investors start to worry a peak may be near, the same feedback loop starts operating in the opposite direction, and asset prices start crashing – often precipitously.

These theories explain how asset prices can deviate from fundamentals for long enough to generate boom-bust dynamics, but they do not imply that we can generate permanent increases in valuations that aren’t driven by fundamentals. Any sustainable improvements must come from addressing the underlying fundamentals that drive long-term performance, rather than simply manipulating the incentives to hold more equity..

In conclusion, forcing individuals to invest in UK equities, such as through ISAs, undermines the investment principle of diversification, and would almost certainly result in worse performance for British savers. It would lead to lower risk-adjusted returns for core savings and significantly increase exposure to UK-specific economic shocks, effectively mandating retail investors to gamble with their financial security. The wealth transfer previously identified would also be substantially more severe under this forced concentration, as it would amplify the impact of any domestic market underperformance on individual retirement outcomes. And crucially, there is no good reason to believe that this would even help British firms, whose success depends on fundamentals.

Pension Mandates: Capacity Constraints and Risk Transfer

Pension funds exist for their beneficiaries: namely, to fund their retirement.

Given this, we should be sceptical of arguments for directing pension savings for almost entirely the same reasons that we should be wary of any plans to encourage retail savings to flow to “UK equities”. All of the operational concerns still apply, particularly on how we might define an eligible investment, but there are separate reasons to be concerned about the performance and sustainability of UK pension funds that may have implications for UK investment more broadly.

Benefits and Contributions

Defined benefit (DB) pension schemes guarantee an indefinite, defined income after retirement, while defined contribution (DC) calculates payouts based on contributions, like a savings account.

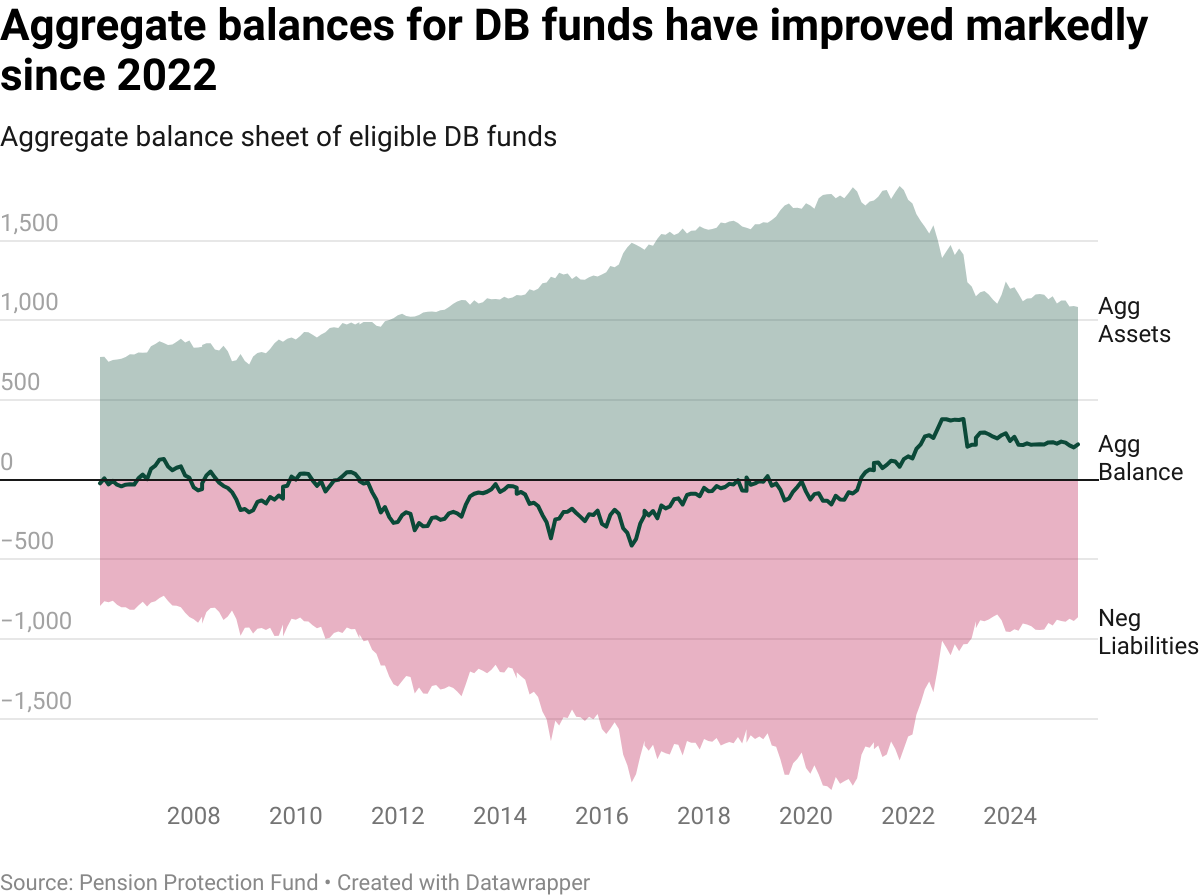

These are very significant sources of private savings. There are just under 5,000 private-sector DB pension schemes in the UK, with aggregate assets of approximately £1.17 trillion and liabilities around £0.95 trillion. Private sector DC schemes hold £289bn in assets, while public sector schemes account for a £548bn, bringing the total market value of UK funded occupational pension schemes to £2,009bn as of March 2024.

DB schemes allocate around 70% of assets to bonds and only around 15% to equities. DC schemes tend to be more growth-oriented, with roughly 76% in equities (around 70% overseas and 6% in UK equities), 12% in bonds, 2% in property, and 9% in alternatives including multi-asset funds.

Given the small proportion of these funds going to UK equities, we can understand why politicians are tempted to try to redirect this capital. However, there is a reason why pension funds are weighted away from UK equities: because, as with ISAs, diversification is important for consumers. To deliberately interfere with this pattern would mean subordinating pension savings to the purpose of providing cheaper funding to struggling “UK equities”, however defined, rather than ensure sustainable retirement funds for millions of working Britons.

That said, there is a stark difference between the investment strategies of pension types. In particular, defined benefit schemes have aggressively reduced their exposure to equities over the last two decades. This could be, if Woodford is correct, in response to changes to the institutional and regulatory environment.

Why does this reduced exposure to equities matter? One reason could be that lower shares in equities lowers returns for pension-holders. Even if only a very small share of these funds would end up funding companies with a meaningful UK footprint, it is plausible that UK-based capital has an outsized effect in helping identify viable investment opportunities, which might then result in additional capital inflows from abroad.

But the solution is to increase the share of equities in general, not UK equities in particular. Left to their own devices, even if DB schemes replicated the behaviour of DC funds and rebalanced towards equities, it is unlikely that much additional UK investment would materialise as a result, at least not without risking forcing pension funds to accept lower returns to subsidise UK companies that might not survive otherwise.

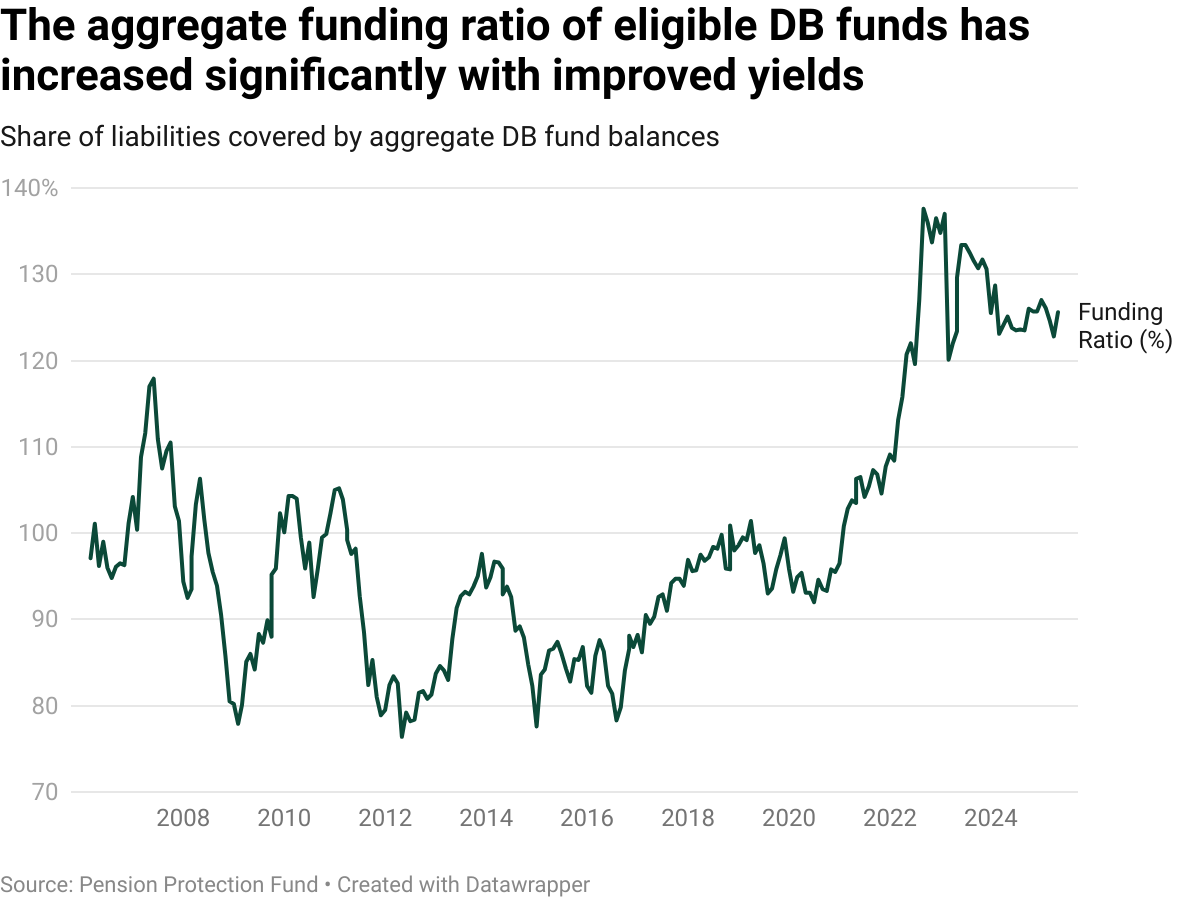

Finally, there is a potential risk that struggling DB funds may be nationalised in the future, with the government taking on the longevity risks associated with longer life expectancies. As relayed by Woodford, the change in portfolio allocations was likely the result of a change in accounting standards forcing funds to recognise the underlying volatility of their positions. Removing this important mechanism of market discipline without an associated behavioural change to reduce exposure to longevity risk could feasibly be interpreted as a subsidy in the form of a potential “bail-out put”.

Current rules have forced an aggressively fragmented landscape of thousands of schemes to reflect the underlying risk of their positions on their balance sheets, resulting in extremely defensive portfolios with a large fraction of debt instruments. To improve the performance of these funds while reducing the total risk associated with holding higher-return portfolios, policy should aim to both increase the level of concentration to allow resulting funds to better handle the volatility, and to incentivise the transition towards a DC framework by reducing the level of exposure to longevity risk. Encouraging a more aggressive investment posture with only minimal changes to the underlying risk might simply end up transferring these costs to the public sector.

Pushing on the string of “UK equities”

According to one analysis, UK venture funds lack capacity to absorb pension-scale capital without forcing allocations to lower-tier opportunities. Top funds are oversubscribed 3-5 times, and accept minimal new capital, while the UK market cannot accommodate billions without substantial return compression. This provides yet more strong evidence that the primary challenge with an increased allocation of funds to companies with a meaningful UK economic footprint lies with the supply of viable investable propositions; a greater abundance of companies with good prospects would mean greater demand for capital. The degree of oversubscription suggests that there is a scarcity of such opportunities.

Investing in venture capital and private equity adds 0.15% in yearly fees, which is more than twice the 0.06% you might save by merging investment funds. Both asset classes typically charge 1.5-2% management fees plus 20% carry on gains. The net impact on member returns is negative as higher fees compound over decades, even before considering capacity constraints that force allocations toward lower-quality opportunities with depressed risk-adjusted returns. The net impact on member returns would be significantly negative as higher fees compound over decades, even before we consider the implications of depressed risk-adjusted returns.

It’s worth pausing here and considering the benefits of compelling a reallocation to private equity in particular. At first glance, there is a stronger case for interventions to increase the share of investment in this type of asset, for two main reasons: strong performance relative to public stocks for a significant timeframe, and a greater deal of difficulty for smaller institutional investors to access these opportunities.

According to John Plender, the outsized returns to private capital may have been overstated by a period of prolonged low interest rates. As rates return to their long-term average, this differential performance may disappear. Historical evidence reinforces this: funds raised at cycle peaks (1999-2000, 2006-07) delivered the weakest returns once valuations normalised. Attempting to push pension funds towards these investments could trigger undesirable impacts on their returns: lower risk-adjusted returns due to excess savings chasing too few investments, compounding transfers through intermediaries through fund fees, and a cyclical decline in these returns from a more conventional interest-rate environment-in practice socialising downside risk to individual pension pots while privatising upside gains for professional investors.

To compound the downward pressure on returns, we must also consider the impact that encouraging a greater proportion of private capital, or venture equity, in fund portfolios would have on costs. According to Alex Chalmers, pension schemes require daily dealing but private assets are revalued monthly using stale marks. This creates systematic wealth transfers where ordinary savers would pay inflated prices for assets already repricing downward, which would be particularly acute given that, for example, 2021 vintage portfolios are still marked at peak valuations despite 25% secondary market discounts.

Moreover, it is not only in the interests of prospective investors to have access to regularly updated pricing signals. Private investments are subject to a lower level of public scrutiny, potentially delaying the detection and notification of any corporate malfeasance. Main market listed companies must issue two sets of results per year in a timely manner. Half year results must be issued no later than three months after period end, with a four month limit for the annual report and accounts. As well as timely information, listed securities are less subject to limits to arbitrage, as short sellers are financially motivated to take advantage of perceived downside price risks - a price discovery mechanism that is lacking in private markets.

Chalmers goes on to discuss examples of other countries with successful pension fund industries, such as Canada and Australia, who make significant investments in venture capital. The key insight is that consolidation, combined with investment decisions based primarily on commercial factors, results in highly diversified funds with the size and expertise to allocate a share of their portfolio to more speculative projects. Critically, however, this emerges as a consequence of a healthier ecosystem and institutional landscape, not from mandated allocations.

What this means for mandated investment

The preceding discussion does not suggest there are no genuine issues with UK capital allocation. A healthier and more robust pension fund industry with greater scale and risk tolerance would have a meaningful role to play in the efficient identification and funding of promising but speculative opportunities, even if access to finance isn't the primary constraint on the success of UK companies.

However, there are four core structural problems that must be addressed to enable this. Addressing these will be more effective than mandating investment.

Four Core Structural Problems

Problem 1: Long-Tail Fragmentation Creating Cost Drag

Both the DC and DB fund landscape show very dramatic levels of fragmentation. There were just under 5,000 DB schemes as of March 2024, and while the vast majority of the DC managed assets are concentrated in under 1000 individual funds, there were over 24,000 micro-funds with fewer than 10 members.

This fragmentation imposes substantial cost penalties: small schemes face £1,054 per member annually, vs £182 for large schemes, trapping 960,000 DB members in sub-£100m schemes which cost £500 more per year than necessary. Total system cost reaches ~£10bn NPV in DB and £8-10bn in DC, plus an ongoing 0.2-0.5% annual fee drag. Consolidation of funds would enable smaller participants to access better pools of investment, and strengthen governance arrangements across the board.

Problem 2: Accounting-Driven Equity Divestment

The shift towards FRS17 accounting rules reflects a necessary introduction of transparency to ensure the true value of pension assets can be observed against reasonable benchmarks. However, an undesirable consequence of this change was to encourage DB funds to divest from equities, leading to a long-term decline in their share of the portfolio.

The scale was extraordinary: DB pension funds shifted from 60-70% equity allocation towards liability-matching bonds, with ownership of UK equities falling from 32.4% of the pension fund market in 1992 to approximately 1.5% today, while bond allocations rose from 28% to over 63%. This reflects a response to regulatory incentives that forced recognition of balance sheet volatility rather than a commercial judgment about UK company prospects, removing £1+ trillion in patient capital from equity markets, and reducing a potentially large problem with moral hazard associated with the mismatch of mostly fixed liabilities and potentially very variable returns.

Problem 3: Information Production Collapse

The venture and start-up ecosystem in the UK suffers from a lack of specialised institutional capital that can support a well-developed research function in financial intermediaries. MiFID 2's implementation in 2018 destroyed what Woodford terms the "symbiotic relationship" between fund managers, brokers, and listed companies-research unbundling eliminated the economic basis for equity research, particularly for smaller companies requiring detailed analysis.

This reduces the efficiency of allocations, because investors cannot easily distinguish between high-value propositions and low-value ones, resulting in lower average valuations and a higher premium for promising new companies. The collapse creates information asymmetries that systematically disadvantage complex enterprises (such as many deep tech ventures) while favouring those with simple, easily-assessed business models.

Problem 4: Dual Risk Concentration in DB Schemes

Encouraging greater equity allocation in DB schemes without addressing their exposure to longevity risk could result in a concentration of risks that increases the probability of future bailouts. Unlike DC schemes, where investment risk is borne by individual members, DB schemes combine investment risk with longevity risk. The shift towards bond-heavy portfolios, while economically damaging, is a rational response to regulatory frameworks that forced recognition of this dual risk exposure.

Implications for Reform Design

An effective reform package should address these four structural problems through targeted solutions that address root causes rather than symptoms. Proposals to mandate pension allocations toward UK private markets risk channelling capital through the same structurally biased mechanisms that favour predictable, collateral-backed investments over innovative enterprises that require patient evaluation. This was seen in the pension fund exodus, which occurred because regulatory frameworks favoured banking-style liability matching over project-specific equity assessment. Mandated allocations risk perpetuating the same systematic biases.

How to reform equity markets

The focus of reform should be on enabling larger and more capable funds to better identify viable opportunities. Ultimately, this will better serve savers, pension beneficiaries and UK companies.

The aim should be to gradually shift the UK toward direct market-based allocation mechanisms that can assess complex, infrastructure-dependent enterprises more effectively, without forcing volumes of investment through market structures that cannot handle them and could build into the system a large risk of future losses.

A successful strategy should also recognise the central role that research and analysis play in helping identify the potential opportunities associated with new companies operating at the technological frontier: the current landscape requires companies to specialise in increasingly sophisticated technologies while lacking the analytical infrastructure necessary to communicate their value propositions to sophisticated capital. Market reforms should enhance selection mechanisms and natural concentration in the sector rather than override them through political direction.

The reforms outlined below will only go so far; more fundamentally, the big challenge facing UK companies is not whether capital flows to the right opportunities, but the adverse business environment in the UK that limits their natural expansion. The solution to this lies in supply side reform, such as in planning and infrastructure.

The Reform Strategy: Two Complementary Tracks

Track 1: Financial Market Microstructure Reforms

This involves facilitating a managed transition toward DC schemes that can support more sophisticated investment strategies, while fundamentally reforming the information production and assessment mechanisms that enable effective capital allocation. This enhances, rather than overrides, market selection processes, through:

- Consolidation mechanisms to address fragmentation through scale and pooling in investment management, enabling smaller participants to access better investment pools while strengthening governance arrangements

- Managed DB-to-DC transition that reduces dual risk exposure inherent in current DB structures while maintaining capacity for patient capital allocation

- Information production enhancement through reforms addressing MiFID 2's unintended consequences, restoring economic basis for detailed company analysis particularly for innovative enterprises requiring complex evaluation

Track 2: Fundamental Competitive Reform

Structural reforms toward abundance and lower input costs represent the only mechanism for ensuring UK firms can achieve competitive positions that make investment attractive on commercial grounds. High energy costs, expensive industrial space, complex planning regimes, and inadequate infrastructure create systematic disadvantages that no amount of forced funding can overcome.

Companies struggling to access funding are predominantly those with unclear pathways to profitability and substantial infrastructure requirements. The CBI's Industrial Trends Survey referenced by The Economist shows UK manufacturers most often cite 'uncertainty of demand' or 'inadequate return' (not 'cost of finance') as primary investment barriers. This suggests that broad capital flows cannot address the underlying regulatory and structural constraints that make potential investments unattractive in the first place.

Pension System Consolidation:

The UK pension landscape is extremely fragmented. This systematically disadvantages fund beneficiaries while constraining capital allocation efficiency. The below consolidation framework addresses two complementary approaches: enabling individual member choice through enhanced transfers, and removing regulatory barriers that prevent beneficial scheme-level restructuring.

Individual DB-to-DC Transfers

Shifting from DB to DC schemes is likely to be mutually beneficial for both fund sponsors and beneficiaries. While defined benefits schemes typically offer an attractive package of inflation-protected benefits that insure individuals against longevity risk, the sponsor’s need to manage these risks has led to a shift to safer assets and an increase in surpluses relative to the size of liabilities.

This means funds take less risk, in order to manage their obligations, and apportion a greater share of recent yield increases from fixed income assets to their surpluses. These schemes would likely have greater appetite for higher risk-adjusted returns if they didn’t have to manage these fixed obligations, and so would be able to apportion more of their portfolio to equities, which could be better for both beneficiaries and UK industry.

Current Transfer Process Barriers

Members of DB schemes have a statutory right to transfer their pension balance to a DC arrangement, but the process is cumbersome, and requires beneficiaries with transfer values exceeding £30,000 to obtain independent financial advice (which can cost around £2,000-5,000).

The current Cash Equivalent Transfer Value (CETV) also reflects only the actuarial cost of providing equivalent benefits, and does not consider the potential economic benefits sponsors might generate by shifting DB liabilities onto a regime that enables a higher-return investment strategy, or enables the reduction of surpluses necessary for the long-term viability of DB schemes. This means there is limited potential for compensation to outgoing members, despite the substantial economic benefit sponsors gain when members transfer out.

The mandatory advice requirement exists due to past misselling scandals, but creates perverse incentives: advisers rarely recommend transfers, due to regulatory liability, while members face substantial costs that often exceed any potential benefit for smaller pensions.

Core Principles

Individual Choice: While sponsors would be empowered to offer compensation packages exceeding the CETV to incentivise transfer, this should be predicated on individual members only electing to transfer out of the scheme if they are convinced that DC offers them a better deal. This enables natural self-selection based on personal circumstances and preferences.

Economic Benefit Sharing: Transfers from DB to DC generate some economic benefits for sponsors: they reduce the longevity risk associated with DB (and is the primary threat to its future viability), there is less accounting volatility associated with discounting fixed future liabilities using the AA discount rate, the risk of future obligations in excess of the market value of the scheme's assets is eliminated, and there is less need for surpluses to insure against these outcomes. There are currently no ways to share these benefits with members, who additionally bear the cost of seeking relevant financial advice, and are therefore incentivised not to consider making what could be a beneficial switch.

Scale and Consolidation: Transfers would be restricted to qualifying DC schemes that meet relevant criteria on scale, governance, and investment strategies. These constraints would help ensure that resulting DC schemes can make higher-return investments, have lower fees and can access higher-performing portfolios.

Practical Implementation

Enable Enhanced Transfer Values: Sponsors would be allowed to offer members transfer values above statutory CETV calculations, funded from the total economic benefits from members transferring out. This would make switching more appealing for members.

Streamlined Advice Process: The reformed process would require participating schemes to secure advice from qualified transfer specialists, funded from the existing scheme surplus, to review the position of members and provide advice once members hit the relevant transfer threshold.

Threshold-Based Advice: As with the current process, members would receive transfer guidance once their CETV reaches the threshold of £30,000, with this advice remaining valid for future transfer requests (subject to periodic updates). This eliminates repeated advice costs while ensuring informed decision-making.

Enhanced Transfer Standards: This would establish a clear regulatory framework allowing enhanced transfer values above CETV calculations for eligible schemes, subject to independent actuarial certification of the relevant offers, transparent member communication, and appropriate safeguards to ensure the scheme would remain viable.

Advice Framework: Eligible schemes offering enhanced transfers must appoint FCA-regulated advisers with pension transfer permissions to provide standardised advice to all members requesting transfers above £30,000. These advisers should be funded from the scheme surplus, maintain professional indemnity insurance, and deliver advice meeting identical standards to current individual requirements but applied across the membership.

Qualifying DC Schemes: Eligible schemes would need to meet minimum standards for inclusion, such as a minimum scale of AUM (potentially around £5bn), a high standard for governance mechanisms, a transparent cost structure, and a viable investment strategy subject to value-for-money principles.

Surplus Utilisation: The mechanism would enable eligible schemes to use their current surpluses (currently totalling £219bn sector-wide, representing 19% of liabilities) to fund both enhanced transfer values and streamlined advice processes, rather than requiring sponsor cash contributions.

Enabling Consolidation

While DC funds have begun to consolidate over the last few decades, scheme-level consolidation in the DB system remains much more limited, which keeps the market too fragmented. There are clear benefits from consolidation for beneficiaries, who pay currently £500 more than necessary in annual fees, and for UK companies, who miss out on the discovery process for high-quality projects domestically, which capital could enable. But consolidation is hampered by structural barriers.

Existing Barriers to Consolidation

DB pension promises are protected by Section 67 of the Pensions Act 1995, which stipulates that the specific benefit structure (retirement ages, salary definitions, indexation rules, spouse benefits, among others) of each scheme must be preserved even when consolidating. A consolidator accepting 50 schemes would therefore need to maintain 50 separate sets of benefit calculations, preserving much, if not all, of the administrative complexity that consolidation seeks to eliminate.

When employers seek to transfer schemes, Section 75 triggers immediate liability for full insurance buy-out costs, which industry practitioners suggest typically require assets substantially above current funding levels to achieve. Additionally, any residual surplus returned to the sponsor faces a 25% tax charge. These combined exit barriers create substantial costs even for consolidations that would generate large efficiency benefits, effectively trapping schemes in inefficient arrangements despite the economic case for consolidation.

Trustees face potential liability for decisions that disadvantage any member group, even when these decisions improve outcomes for most members. The legal standard requires demonstrating that consolidation is prudent and fair for members overall, which can be a high bar to clear given members’ diverse circumstances. This leads to decision paralysis, where trustees avoid beneficial changes due to litigation risk.

The Pensions Regulator (TPR) lacks the resources and expertise to assess hundreds of complex consolidation proposals simultaneously. Each transfer requires a detailed evaluation of benefit compatibility, governance quality, and member impact. The regulatory bottleneck means even willing participants face years-long approval processes.

This in turn results in a relatively underdeveloped consolidator market because legal barriers to the rationalisation of benefits prevent economies of scale. Without predictable deal flow and standardised processes, few entities invest in the sophisticated systems needed for large-scale consolidation.

Standardisation and Targeted Enforcement

Rather than completely transforming the legal framework, pension consolidation should be pursued by establishing universal standards while targeting interventions where they can be most effective within existing constraints.

Universal Sustainability Assessment: A first step would be to have TPR make benefit sustainability assessments mandatory for all DB schemes, which would evaluate the probability that schemes can deliver their promised benefits over time. This would be the converse to traditional value-for-money tests that focus on investment performance relative to costs for DC schemes. An assessment of sustainability for a DB scheme would examine funding trajectory, covenant durability, actuarial plausibility, and governance effectiveness, which are the main factors that determine whether members will actually receive their contractually promised benefits.

Such an assessment would establish a single standard that could be applied fairly across the industry while focusing on ensuring member benefits remain protected.

Proportionate Consequences: Schemes that fail sustainability assessments would face consequences appropriate to their circumstances. Large schemes would receive improvement notices and regulatory oversight, with clear timelines for addressing identified deficiencies. For schemes under £100m that fail assessments, TPR would require trustees to conduct a formal comparison with consolidation options, which would entail obtaining transfer proposals from accredited DB Master Trusts and assessing whether consolidation would better serve member interests than remaining independent.

All schemes would retain the fundamental choice of independent operation, but smaller schemes facing genuine sustainability challenges would gain access to professional alternatives when trustee-led reform proves insufficient to return the fund to viability. The framework ensures that consolidation occurs only where it demonstrably enhances member security.

DB Master Trust Structure

Master Trusts operate through ring-fenced sections that pool assets for investment management while maintaining separate liability calculations for each participating scheme. This structure enables participating schemes to take advantage of institutional-scale investment opportunities (which might include infrastructure, private equity, or sophisticated diversification strategies) without requiring benefit harmonisation or compromising the legal protections under Section 67.

Following this arrangement, each legacy scheme would preserve its distinct benefit structure but share professional governance, administration systems, and investment management. A Master Trust managing £5bn across multiple ring-fenced sections would be better positioned to negotiate institutional terms, access alternative investments, and employ sophisticated risk management that individual schemes cannot achieve independently, while maintaining the specific pension promises each scheme provides to its members.

Operational Efficiency: A Master Trust managing £5bn across 50 ring-fenced sections could still deliver significant, albeit limited, economies of scale without the legal complexity of benefit harmonisation. Shared professional governance, administration systems, and investment management could help reduce costs while maintaining the distinct benefit promises each scheme provides to its members.

Diversified Risk Management: Master Trusts aggregate schemes with different covenant profiles whilst maintaining separate liability calculations. This pooled structure enables professional governance and administration systems that may be uneconomical for individual schemes to maintain independently. Regulatory oversight becomes more manageable when focused on a smaller number of large, professionally managed entities rather than dispersed across numerous individually governed schemes.

Market Development: This framework creates predictable consolidation opportunities that justify investment in sophisticated administration and governance systems, whilst enabling TPR to focus oversight resources on a manageable number of large, professionally managed entities rather than monitoring thousands of individually governed schemes.

What Would TPR Assess in Practice?

Funding Trajectory Analysis: Schemes with persistent deficits, deteriorating funding ratios, or unrealistic recovery plans pose genuine member risks regardless of current covenant strength. Assessment would examine whether schemes demonstrate credible pathways to full funding.

Covenant Durability: Evaluation of sponsor financial health, sector prospects, and ability to meet long-term funding requirements. A scheme backed by a declining industrial employer faces different sustainability challenges than one sponsored by a stable public body.

Actuarial Realism: Review of discount rate assumptions, longevity projections, and inflation expectations that systematically understate liabilities, creating false funding security while building future crises.

Governance Effectiveness: Assessment of professional trustee capabilities, investment strategy sophistication, and ability to manage complex liability structures at appropriate scale.

The framework outlined above transforms sustainability assessment from traditional efficiency metrics into member protection mechanisms with more meaningful consequences. Schemes that cannot demonstrate credible benefit delivery face mandatory consolidation with entities that can provide enhanced security through professional scale, whilst preserving the existing legal rights possessed by every member.

More extensive transformation of the DB system would likely require overriding Section 67 protections and forcing benefit harmonisation – changes that could not guarantee preservation of members' contractual entitlements (which exist to protect members from excessive regulatory intervention).

Restoring Research Coverage

Beyond the pension system, aspects of the UK's market microstructure act as direct impediments to its efficiency, particularly affecting viable Small and Mid-Cap (SMID-cap) companies seeking growth capital. The reforms outlined below aim to enhance the information production and price discovery mechanisms that enable better identification of genuinely promising opportunities, while addressing the systematic disadvantages that banking-style allocation creates for innovative enterprises that require sophisticated evaluation.

The MiFID II Research Decline

The introduction of MiFID II in 2018, with its mandated unbundling of payments for investment research from execution commissions, is a prime example of well-intentioned regulation creating unintended market distortions. The original intention was sound. The aim was to increase transparency and reduce potential conflicts of interest,where brokerage commissions might subsidise research of questionable value to end-investors. However, a significant and widely observed unintended consequence has been a material reduction in research coverage, especially for SMID-cap firms.

The economic mechanics behind this are straightforward: the direct payment model for research proved challenging for both research providers, who face high fixed costs in producing quality analysis, and for asset managers, particularly smaller ones, who faced new budgetary pressures for research that was previously implicitly bundled. This disruption to the established economics of research production made it economically unviable for many brokers to continue covering smaller companies.

Market Impact on Capital Allocation

The research coverage collapse particularly disadvantages companies that require project-specific evaluation, rather than standardised banking assessment criteria. Without detailed analyst coverage, sophisticated investors struggle to distinguish between viable opportunities and poor prospects, leading to systematic undervaluation of complex enterprises and reduced capital availability for promising companies.

This reinforces the UK's banking-dominated capital allocation, where collateral-based lending becomes the default funding source for companies that cannot easily communicate their value propositions to institutional investors. The resulting inefficiency constrains patient capital deployment precisely where it could be most beneficial for long-term economic growth.

Targeted Solutions

Reforms should include the following:

Domestic Commission Sharing: Permit commission sharing arrangements for research on UK companies below £1bn market cap, when trading on UK venues through UK-authorised managers. This would create a territorial carve-out that restores the economic model supporting SMID-cap research without undermining MiFID II's broader transparency objectives.

FCA Territorial Clarification: Establish clear guidance that UK CSA exemptions apply to UK-domiciled managers trading UK equities, providing legal certainty for market participants while maintaining appropriate cross-border compliance frameworks.

Collective Research Mechanisms: Create regulatory pathways to allow UK pension funds to jointly commission independent research on UK SMID-caps, thereby avoiding inducement rules while enabling pooled funding for coverage of domestically important companies. This leverages the consolidated pension capital created through the kinds of reforms outlined in the previous section.

Industry Collaboration: Support collaborative research initiatives where multiple UK institutions can pool resources for coverage of companies requiring sophisticated analysis, creating sustainable funding models for high-quality research production.

This framework restores information production capabilities that enable effective capital allocation while working within existing regulatory frameworks including MiFID II's transparency objectives. This would directly support a transition from banking-dominated to market-based capital allocation mechanisms.

Transaction Cost Reduction

Liquidity constraints are a barrier to efficient capital allocation. Stamp Duty on share transactions creates friction that particularly disadvantages the sophisticated funds created through pension consolidation. These transaction costs impede the price discovery mechanisms essential for directing capital towards viable opportunities.

The Stamp Duty Friction Problem

Stamp Duty, currently levied at 0.5% on UK share transactions, creates a direct transaction cost which demonstrably reduces market liquidity. The tax discourages frequent trading, as "the 0.5% can add up where there's high frequency and volume of transactions".

This effect is particularly pronounced for actively managed investments, which potentially discourages sophisticated market participation, reducing price discovery efficiency. Reduced liquidity translates into higher capital costs for listed companies, as investors demand premiums for holding less liquid assets. France introduced a financial transaction tax in 2012 at 0.2%, while Germany does not have one, with both being more competitive than the UK's 0.5% rate.

Capital Allocation Impact

A lack of liquidity hampers the ability of larger, more sophisticated funds to adjust to new information about company prospects. Illiquidity also constrains the size at which asset managers can responsibly operate open-ended funds whilst meeting daily redemption requirements, undermining the economics of UK SMID-cap asset management. This impedes the price discovery process that should guide capital towards the most promising opportunities..

For consolidated pension funds managing £25+bn in assets (perhaps created through the reforms outlined earlier), Stamp Duty would hit, and discourage, the kind of active portfolio management that is needed for sophisticated investment strategies.

Fiscal Impacts

Revenue Challenge: Stamp taxes on shares and other liable securities generated £3.2bn for the Treasury in 2023-24, which is significant. Eliminating or substantially reducing Stamp Duty would create a material shortfall requiring carefully designed alternative sources.

Alternative Revenue Sources: One other option is to remove Business Asset Disposal (BAD) relief, which was claimed by 47,000 taxpayers on £12.5bn of gains in 2022-23, resulting in a total tax charge of £1.2bn. This is substantially below the £3.75bn that would be generated at standard capital gains tax (CGT) rates, and is therefore equivalent to approximately £1.5bn in annual tax relief. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has identified this relief as particularly problematic and called for BAD relief to be removed.

Similarly, the current system of "uplift at death" creates a "big incentive to hold onto assets that have risen in value until death", distorting efficient capital allocation. The IFS also recommends abolishing uplift at death as part of comprehensive CGT reform.

Progressive Targeting: Any offsetting measures could incorporate progressive elements, such as ISA contribution caps that target the wealthiest while preserving benefits for the vast majority of savers. With total ISA market value reaching £725.9bn in 2022-23, targeted reforms affecting total contributions above £500,000 could generate some revenue whilst ensuring market efficiency improvements don't disproportionately benefit wealthier savers. This would represent a small amount of revenue in comparison to the reduction in the costs associated with the stamp duty, but it would help prevent the vast majority of these benefits from flowing to those already gaining the most from a reduction in transaction tax.

Expected Outcomes

Reduced risk: Scheme-level consolidation would transfer members from micro-schemes to professionally managed DB Master Trusts and high-quality DC arrangements. This reduces operational risk while maintaining benefit security through enhanced governance and financial oversight. Ring-fenced DB structures preserve legal protections while increasing institutional scale in investment management.

Better allocation: Consolidated funds with substantial scale can deploy patient capital more effectively, supporting detailed due diligence on complex opportunities that banking-style allocation mechanisms struggle to evaluate. DB Master Trusts managing billions in pooled assets can access infrastructure, private equity, and sophisticated strategies previously unavailable to fragmented schemes. This directly addresses the UK's challenge of banks dominating capital allocation, by creating market-based mechanisms capable of project-specific evaluation.

More efficient markets: Restored research coverage and reduced transaction costs improve price discovery, particularly benefiting enterprises requiring sophisticated evaluation rather than standardised banking assessment criteria. Enhanced analyst coverage enables more informed investment decisions and accurate price discovery, ensuring capital flows efficiently towards viable companies, while also reducing the cost of capital for SMID-caps through improved information production. Eliminating or reducing Stamp Duty would improve market liquidity, narrow spreads, and enhance the UK's attractiveness as a financial centre.

Immediate Cost Reductions: The 960,000 members currently paying £500 a year more than necessary in sub-£100m schemes gain immediate access to professional management, institutional investment pricing, and economies of scale through mandatory consolidation of persistently underperforming arrangements. DC consolidation eliminates the administrative waste of thousands of micro-schemes while ensuring high-quality provision through authorised Master Trusts.

Fiscal Responsibility: The ISA contribution cap limits the extent to which market efficiency improvements disproportionately benefit high-wealth individuals, while providing partial fiscal compensation for transaction cost reductions. This is a progressive approach to capital market reform that supports broader economic efficiency while maintaining responsible public finances.

A stronger business environment

Reforms to the pension system and financial regulation can, over time, improve the long-term performance of retirement portfolios, and give British households greater security and prosperity. They may even improve the venture landscape by gradually increasing the amount of domestic capital with relevant expertise to improve how financial markets identify and fund new opportunities. But we should temper expectations: without significant improvements on the supply side of the real economy, these reforms will have a relatively small impact, especially given how oversubscribed many venture investment products are at the moment.

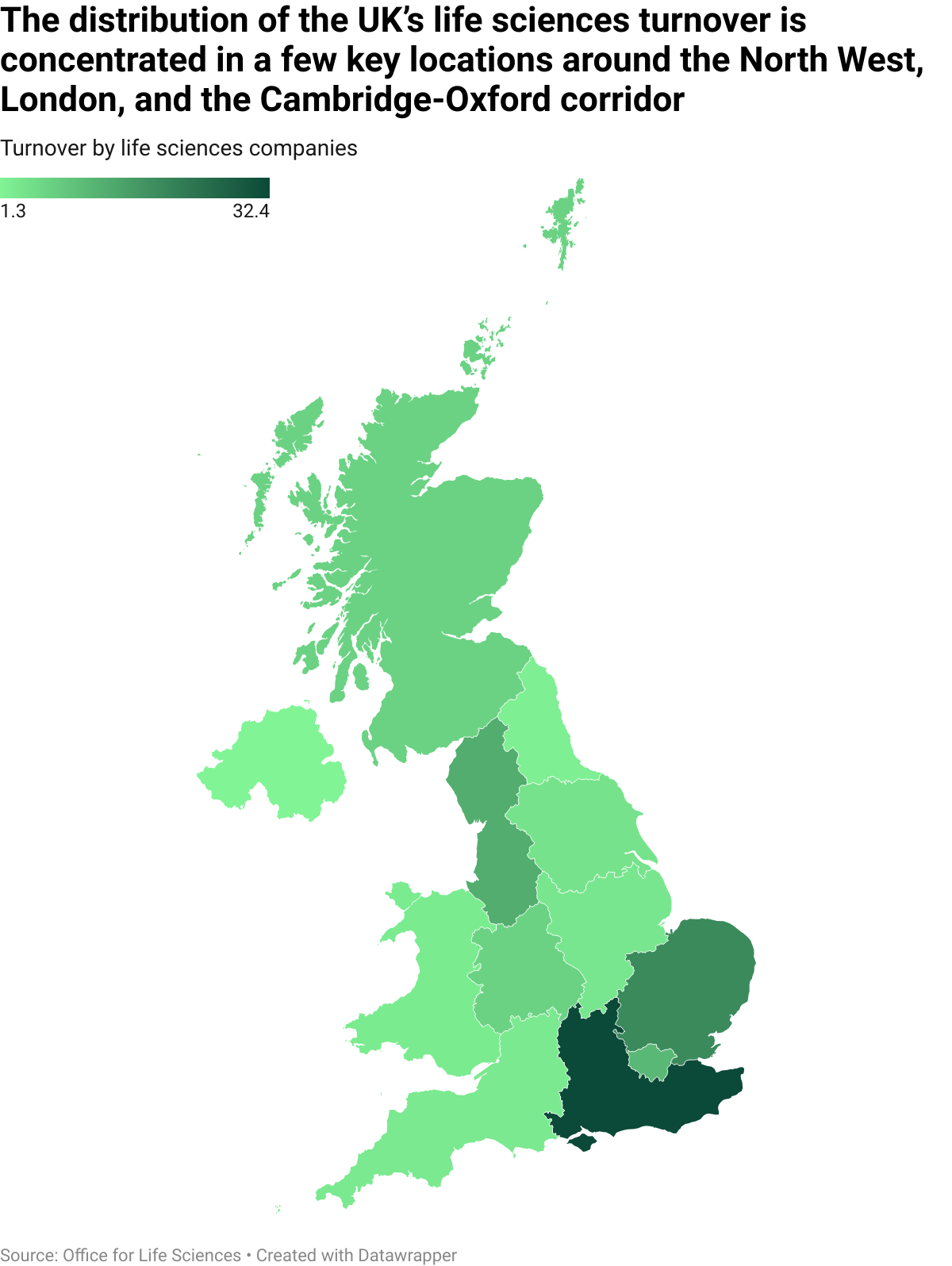

The UK's capital allocation challenges reflect deeper structural constraints that make British companies less competitive, particularly those businesses which are more sensitive to input costs or the availability of the relevant physical infrastructure. Meanwhile, companies with a more modest physical footprint remain internationally competitive, not least because of the large agglomeration benefits associated with space-constrained places like London or the Cambridge-Oxford corridor, while these challenges are increasingly acute for everybody else. Addressing these fundamentals is essential for creating conditions where investors willingly bear the risks associated with patient capital deployment.

The Infrastructure and Input Cost Challenge

Companies requiring substantial infrastructure investment face systematic disadvantages in the UK's high-cost environment. The UK has the highest industrial electricity prices in the world. This particularly affects activity like data centres, for which around 20% of the total cost base is electricity.

Not all growth depends on intensive electricity consumption, but as data becomes an increasingly valuable input to economic activity, the need to deploy this kind of infrastructure at scale will only increase. If the UK remains uncompetitive in this dimension, the resources and investment required to deploy them will simply move elsewhere.

Another example is land. According to research by Savills, rents had increased by 36% by the end of 2023 in Cambridge – one of the most productive parts of the country – and the occupancy rate of laboratory spaces was below 3%. The combination of extremely low vacancy rates and high prices is highly indicative of substantial shortages in the supply of this key input to production.