Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Context: decades of delay and failure

- 3. How defence procurement is supposed to work

- 4. Fixing the five sins of UK defence procurement

- 5. A word of caution: procurement reform is not a silver bullet

- 6. Authors

Summary

UK defence procurement routinely misses cost and schedule targets, leaving the armed forces without the equipment they need, when they need it. This is the product of five sins:

- Overspecification – a bias towards bespoke, over-complex projects that take on unnecessary technical risk when simpler, proven options exist.

- Inter-service rivalry – competition for prestige and budget between the services, driving duplicated capabilities and distorting investment decisions.

- Short-termism and optimism bias – persistent underestimation of cost, time and risk, reinforced by annual cash limits and frequent churn in project leadership.

- Weakening sovereign capability – a “feast and famine” pattern of orders and a failure to take a strategic approach to sovereignty that have hollowed out critical UK-based industrial capacity.

- Slowness to innovate – procurement cycles and commercial rules that favour large primes and pilots over rapid adoption of software-driven, AI-enabled capabilities.

To tackle these five flaws, we should:

- Overspecification – flip the default from bespoke design to proven kit:

- Require an “off-the-shelf test” for every major project, with bespoke development allowed only via explicit ministerial direction.

- Freeze requirements after nine months, with any later changes signed off by the Secretary of State and funded from the sponsoring Service’s own budget.

- Create a permanent “90-day fast lane” for buying trusted, unmodified NATO/allied equipment off the shelf.

- Inter-service rivalry – strengthen the centre while pushing some power closer to the frontline:

- Extend the National Armaments Director’s (NAD) tenure to match major programme timelines, ensuring continuity and accountability.

- Establish an independent UK CAPE-style cost analysis unit to provide unbiased estimates of cost, risk and alternatives.

- Give the NAD a concept-stage veto on new programmes, overridable only by a public ministerial direction laid before Parliament.

- Publish a quarterly readiness ledger, signed by the NAD, to expose raids on spares and training used to balance in-year budgets.

- Increase brigade-level discretionary spending authority for off-the-shelf purchases that meet urgent operational needs.

- Short-termism and optimism bias – align money, incentives and reality:

- Adopt P75 cost and schedule baselines for all projects over £20 million, with clearly ring-fenced contingency.

- Introduce automatic multi-year capital flexibility for the Equipment Plan so funding can move between years without constant Treasury approval.

- Keep Senior Responsible Owners in post for at least five years, with incentives linked to delivery rather than initial approval.

- Weakening sovereign capability – use procurement to rebuild resilience where it matters:

- Disapply current social value criteria in defence, which add cost while doing little to strengthen strategically relevant UK capacity.

- Introduce a consistent UK prosperity weighting for selected categories, heavily favouring meaningful UK activity (employment, IP, supply chains, manufacturing and assembly).

- Professionalise defence procurement as a strategic supply-chain function, recruiting experienced commercial leaders and using combined government data to map and develop the UK defence-industrial base.

- Slowness to innovate – create a real market for challenger defence technology:

- Make “time to first use” a core metric in business cases, with every project required to set and justify an explicit band for time to deployment.

- Focus accelerators on genuine start-ups, moving later-stage firms into mainstream procurement routes.

- Unbundle hardware and software in major contracts so specialist software companies can compete directly rather than through primes.

- Remove entry windows from framework contracts, moving to rolling, dynamic markets that new suppliers can join at any time.

- Sponsor security clearances and provide central secure facilities for early-stage firms to break the current “no clearance, no work” trap.

- Allow initial batch production outside standard competition rules, within defined caps, to test promising technology at scale.

- Enforce the 10% ringfence for novel technologies, with published criteria and transparent reporting on how funds are used.

- Permit upfront, in-full payment for selected contracts to enable start-ups to build factories and scale operations in Britain.

Context: decades of delay and failure

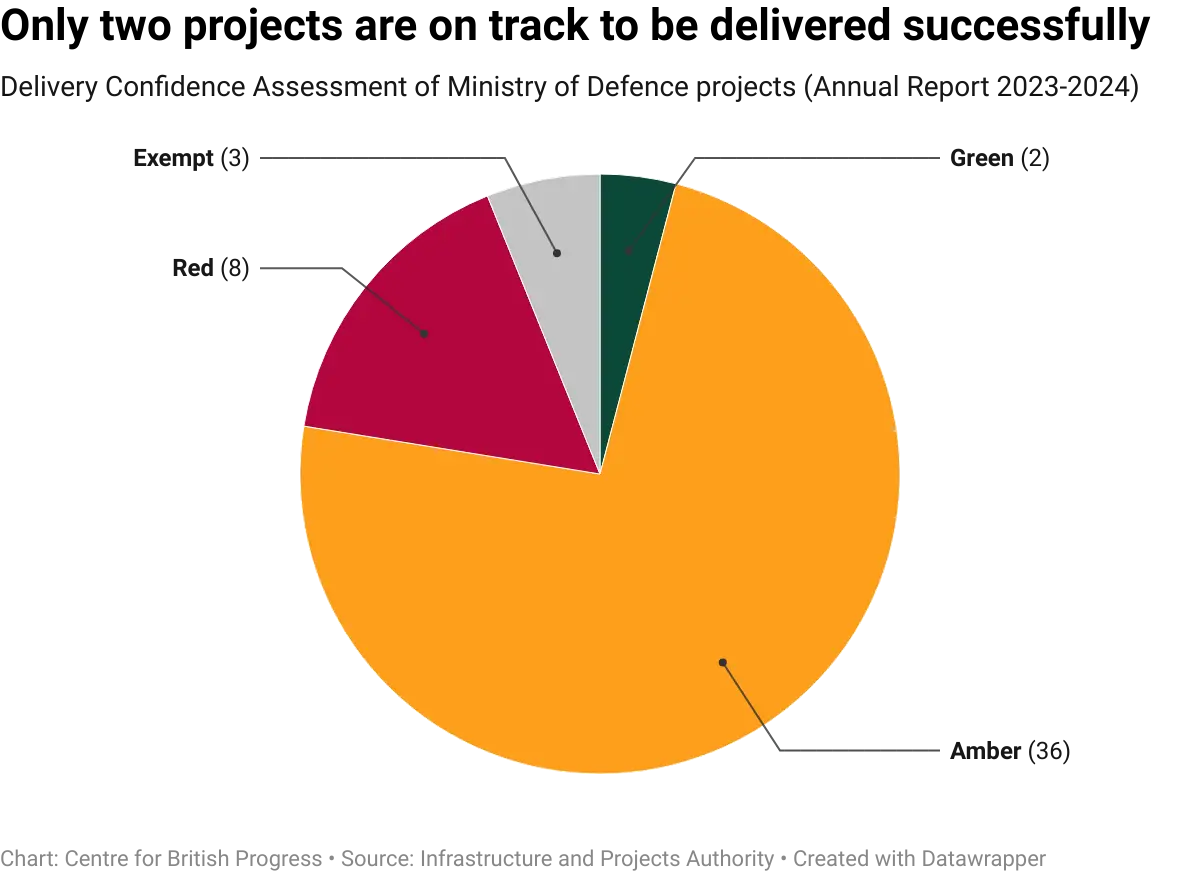

The UK’s defence procurement system has repeatedly failed to deliver operational capability on time, at cost, or at all. According to the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, two of the MoD’s 49 major defence projects are currently on time and on budget.

In the past decade, the British defence sector has experienced a number of avoidable failures:

- The Ajax armoured vehicle, intended to replace Cold War-era reconnaissance platforms, remains unfielded more than a decade after contract award. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) was forced to suspend trials for over a year due to excessive noise and vibration that injured test crews, and the programme is now running eight years behind schedule.

- The Warrior Capability Sustainment Programme, intended to modernise one of the Army’s family of armoured vehicles with new turrets and digital architecture, was cancelled in 2021 after close to £600 million was spent and no vehicles delivered.

- In the air, the E-7 Wedgetail was supposed to replace the RAF’s retired airborne radar fleet, but the order was cut from five to three aircraft and delivery slipped by three years.

- At sea, the Type 31 frigate – designed as low-cost general-purpose escort – has already slipped from 2029 to 2030, with Babcock, the contractor, booking £190 million in associated losses. Only half the Navy’s fleet of Type 45 destroyers, its core air-defence ships, are operational after a series of significant engine failures.

These failures are not limited to manned platforms. The Morpheus tactical communications programme, intended to replace the Army’s Bowman network, has cost more than £760 million without fielding a working system. Entry into service is now unlikely before 2031, and the core contract has been terminated. In 2024, the MOD officially announced it was scrapping Watchkeeper, the Army’s long-running tactical unmanned aerial vehicle programme, after eight crashes and over £1.3 billion in sunk costs.

At the same time, MOD is broke. UK defence spending has fallen dramatically over time. When the UK defeated Argentina in the 1982 Falklands War, defence spending sat at 4.5% of GDP. When the UK invaded Iraq it sat at half this total, and in 2015-2016, the UK was barely meeting the 2% NATO target.

The UK’s last Defence Equipment Plan, published in 2023, contains a £16.9 billion black hole and was dubbed “unaffordable” by the National Audit Office. The government has not published revised numbers over the past two years, arguing that the next plan should be postponed until after the Strategic Defence Review.

Despite this persistent refusal to prioritise defence investment, the UK maintains the trappings of a Tier One global power: continuous nuclear deterrence, carrier strike, a leading NATO role, and forward deployments from Estonia to the Indo-Pacific. Flagship programmes like the Dreadnought-class submarines – a £30–40 billion replacement for the UK’s ballistic missile fleet – and the Global Combat Air Programme, a sixth-generation fighter jet co-developed with Japan and Italy, illustrate the scale of those ambitions. Both are technically demanding, decades-long undertakings with steep cost profiles and no short-term operational payoff.

Procurement failure is dangerous. The war in Ukraine has seen swarms of drones, precision strike and pervasive electronic warfare. Iran’s proxies have disrupted shipping lanes. Hostile states are probing our energy networks, undersea cables and cyber defences. Against this backdrop, the UK suffers from thin air and missile defence, low stocks of munitions, weak anti-submarine warfare, along with a weak industrial base. In a crisis, we would see avoidable deaths and the store cupboards would be bare within days. The UK’s present situation undermines NATO’s deterrence, invites coercion, and puts British service personnel, merchant crews and civilians at needless risk at home and overseas.

As these risks have worsened, reform has lagged. For over two decades, successive UK governments have promised to fix defence procurement. Review after review since the 1990s has diagnosed the same set of problems: spiralling costs, late delivery, and over-specification. In the meantime, the UK’s defence-industrial base has continued to wilt, as declining spending has led to production lines shuttering or firms being acquired by overseas competitors or private equity.

The official response has followed a familiar script. Reforms over the past 25 years have tweaked governance structures, revised approvals processes, and significantly increased the volume of management jargon, but they have left incentives untouched. This is why similar problems reappear across programmes and decades. Without a concerted effort to tackle the economic and institutional logic of procurement, the system will continue to fail in predictable ways, no matter how often it is reorganised.

The 2025 Strategic Defence Review, accepted in full by the government, contained a number of important reforms. These include:

- The creation of UK Defence Innovation – a £400 million unit that will find technology currently on the market and opt for ‘good enough’ solutions on three-month cycles. The goal is to move promising products directly into funded procurement cycles, rather than leaving them stranded as pilots.

- The creation of Defence Research and Evaluation – a research organisation that that concentrates on a small set of critical in-house skills (such as protection against chemical or biological threats, advanced weapons concepts, and specialist munitions), funds early scientific work in priority areas, builds long-term research partnerships with a handful of trusted universities.

- The introduction of the segmented procurement model: ends the division between the Services and shifts money and decision-making into shared capability portfolios and then runs three different buying routes:big platforms bought through long-term partnerships with two-year contract timelines; modular upgrades competed on one-year cycles; and quick commercial tech purchases completed in three months using dedicated fast-lane funding. At least 10% of model’s equipment budget will be spend on novel technologies each year..

Acting on this now is essential. As the Prime Minister said in his foreword to the Strategic Defence Review, “the pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of relying on international just-in-time supply chains … we must drive a new partnership with industry and a radical reform of procurement”. But MOD has seen enough grand strategies and exhortations to reform.

Since the publication of Strategic Defence Review in June, little seems to have happened. The government promised an investment plan in the Autumn, but has not yet delivered one. At a recent event, Richard Barrons, former Commander of Joint Forces said that: “What’s happened in the intervening four months is very little.” Grace Cassy, one of the independent reviewers of the document, accused MOD of ignoring the spirit of some of the recommendations. Without sustained reform, as well as a concerted effort to refire the UK’s defence-industrial base, the ambitions in the review will remain undelivered and undeliverable.

How defence procurement is supposed to work

Defence procurement in the UK theoretically runs through a gated lifecycle, overseen by a dedicated delivery agency, governed by two sets of commercial rules, and audited rigorously by the Treasury, National Audit Office, and Parliament.

To understand where the process is wrong, it is important to grasp how it is supposed to work.

1) Requirement setting

- The frontline commands (Royal Navy, Army, Royal Air Force, and Strategic Command) identify a capability gap or obsolescence, they produce a set of requirements.

- The MOD balances these requirements against the ten-year Equipment Plan and overall defence budget agreed with the Treasury. The plan is meant to be refreshed annually (but hasn’t been since 2023) and then scrutinised by the National Audit Office, which will assess whether it is affordable. While the NAO can (and does routinely) deem the plan unaffordable, this is not a formal obstacle.

- The plan is factored into the government’s wider Defence Industrial Strategy, which balances questions about skill and export potential.

2) Purchasing

- The actual buying is managed by a number of different agencies, but they follow the same approval gates and commercial rules:

- Defence Equipment & Support (commonly known as DE&S): an arms-length body of approximately 12,500 staff that is responsible for negotiating and managing most equipment and support contracts on behalf of the Armed Forces.

- Defence Digital: part of Strategic Command, responsible for buying IT and cyber systems

- Defence Infrastructure Organisation: responsible for estates and construction.

- There are two main sets of contract rules:

- Competitive tenders: the default means of awarding contracts, where suppliers bid for the work. MOD chooses the offer that gives the best overall value, based on cost, quality, and delivery time. Prices are set by the winning bid, profit margins are uncontrolled, and key details of the contract must be published and monitored.

- Direct awards: the MOD can avoid running a competitive process in special cases (e.g. national security, operational urgency, lack of alternative suppliers), awarding contracts directly under the single-source regime. These contracts are priced using a cost-plus formula set in law to compensate for the lack of competition.

3) Project life cycle

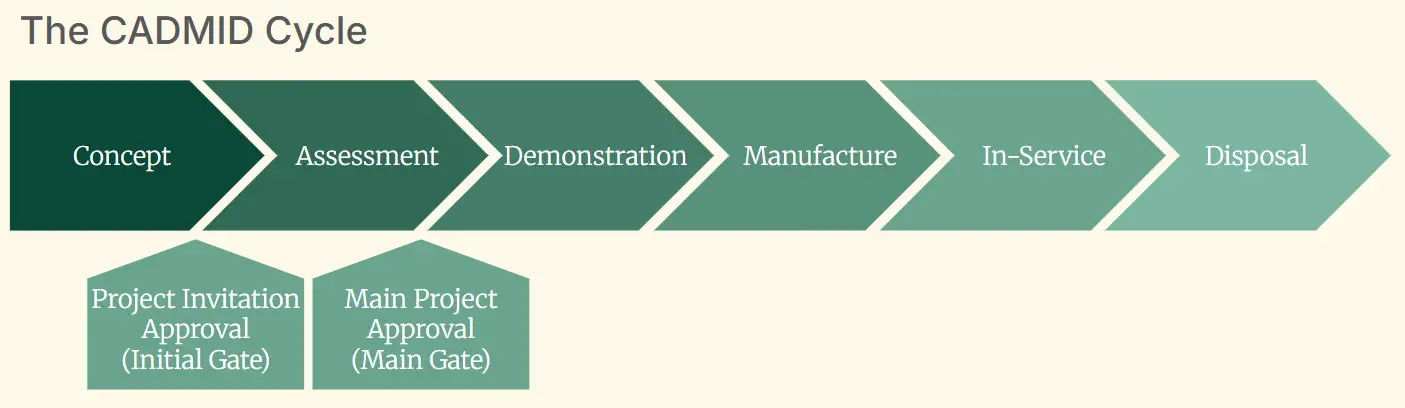

Every project then goes through the same CADMID cycle: Concept, Assessment, Demonstration, Manufacture, In-service, Disposal. The main investment decision sits between Assessment and Demonstration. Nothing expensive should be ordered until a costed, risk-tested business passes this test.

4) The segmented procurement model

In 2024, the MOD adopted the Integrated Procurement Model, which was meant to streamline the CADMID lifecycle and get working capability into service within five years (three for software). From 2025, the department has started to overlay this with a segmented procurement model, which changes how programmes are grouped and bought rather than replacing CADMID outright.

Under this model:

- Funding and planning are organised into shared capability portfolios rather than separate single Service programmes. Each portfolio is supposed to own the full, through-life cost of its equipment and support, and to decide how much to put into big platforms, upgrades, and fast experimentation.

- There are three distinct buying lanes, as opposed to a single one-size-fits-all path:

- A lane for major platforms (ships, aircraft, armoured vehicles) bought through long-term partnerships, with an expectation that the first main contract is agreed in about two years rather than after a protracted design phase.

- A lane for spiral, modular upgrades, where sensors, weapons, software and sub-systems are competed regularly, using common standards and “plug-and-play” designs, with contracts let on roughly annual cycles.

- A rapid exploitation lane for smaller, commercial or dual-use technologies, where contracts are meant to be placed in a matter of months, using simple, repeatable frameworks and a protected pot of money that is not easily raided to cover overruns elsewhere.

Frontline commands still set requirements, but they are now expected to frame them as problems and outcomes inside these portfolios (“we need to defend X against Y”), rather than as fixed, bespoke platform specifications.

Fixing the five sins of UK defence procurement

UK defence procurement has long suffered from five interconnected flaws:

- Overspecification: a bias in favour of bespoke, overly-complex projects that take on significant technology risk, even where simpler solutions are available.

- Inter-service rivalry: competitions for prestige and budget between the services leading to capabilities being either duplicated or degraded.

- Short-termism and optimism bias: a persistent underestimation of costs, amplified by Treasury rules that force decisions on multi-year programmes into single-year budgeting cycles;

- Weakening sovereign capability: a ‘feast and famine’ approach to orders and a lack of industrial strategy leading to the domestic military-industrial base atrophying;

- Slowness to innovate: multi-year procurement cycles and a bias towards large defence primes preventing critical technologies reaching the frontline in a timely way.

Resolving these will require concerted action from both the Ministry of Defence and the Treasury, using a mixture of existing powers and amendments to primary legislation.

1) Ending overspecification

The Integrated Procurement Model is one of the more recent in a long series of MOD planning documents emphasising the importance of buying off-the-shelf technology, and for good reason. The history of UK defence procurement is littered with projects that took on far more technology risk than necessary. This usually manifests in MOD demanding scores of changes to equipment that could be bought off-the-shelf or the decision to commission bespoke designs from scratch.

This is exemplified by Ajax and Watchkeeper.

Ajax started out life as a relatively simple platform that the Army planned to use for reconnaissance, based on an existing European armoured vehicle. 1,200 capability requirements later, it had a new 40mm cannon with advanced fire-control, new computer systems, and thicker armour. Many of these technologies, such as the cannon, had never actually been built or deployed before. A National Audit Office report concluded that: “The Department’s and GDLS-UK’s [the contractor] approach was flawed from the start as they did not fully understand the scale or complexity of the programme … the Department and GDLS-UK did not fully understand some of the components’ specifications or how they would be integrated onto the Ajax vehicle.”

Full delivery looks likely in 2029, 15 years after MOD placed the order.

The Watchkeeper programme was intended to be a replica of the highly-performant Hermes-450 drone, MOD added an unproven ground-mapping radar, automatic take-off system, and full civil airspace certification. While each addition may have sounded reasonable in isolation, the 2,000 systems requirements led to a drone that was so heavy it struggled with take-off. The 54 drones, which cost over £1.3 billion, will come out of service next year having seen little use.

These delays are wasteful and result in capability gaps going unfilled or old equipment being stretched long beyond its retirement date.

This urge to overspecify is in part driven by the understandable cultural sense that the military should always have ‘the best’. Paradoxically, it also stems from resource constraints. Amid a shrinking equipment plan, projects that combine more capabilities can be branded as flagship modernisation programmes. This boosts their internal priority and protects them from cancellation. For example, the Army could argue that Ajax was not just a reconnaissance vehicle, but a multi-use armoured vehicle that was interoperable with NATO and equipped with the latest digital systems.

Defence’s dependence on a small number of big contractors means that suppliers have little incentive to pushback on outlandish requests. Every additional requirement is billable work, and poor delivery is no bar to future work. In the UK, reopening a contract to add more requirements is an expected part of the process, while in France, a material change of requirements needs specific ministerial sign-off.

These exquisite systems increasingly resemble the product of a different age. Among Ukrainian drone operators, for example, the most popular and effective drones have often been the cheapest and simplest, most notably civilian DJI drones bought off the shelf from China. As well as being easy to use, their relatively straightforward electronic signatures makes them harder for Russian electronic warfare to isolate and jam them. Meanwhile, the beautifully crafted drones produced by Western start-ups, laden with advanced capabilities, were easy pickings.

MOD procurement culture will need to adapt to what former US Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Development and Emerging Capabilities, has called the age of ‘precise mass’:

“Militaries find themselves in a new era in which more and more actors can muster uncrewed systems and missiles and gain access to inexpensive satellites and cutting-edge commercially available technology. With these tools, they can more easily conduct surveillance and stage accurate and devastating attacks. Its imperatives already shape warfare in Ukraine and the Middle East, influence dynamics in the Taiwan Strait, and inform planning and procurement in the Pentagon.

In the era of precise mass, war will be defined in large part by the deployment of huge numbers of uncrewed systems, whether fully autonomous and powered by artificial intelligence or remote-controlled, from outer space to under the sea.”

This will mean buying (and ideally manufacturing) cheap equipment, rapidly and at scale, much of which will be comparatively low spec. MOD will need to turn the page on the era of overpaying and overwaiting for ‘the best’.

The segmented procurement model, by focusing on outcome over specification, should theoretically solve some of these challenges, but it will rely on major cultural change within defence.

Outcome-based problem statements demand more analytical work upfront (e.g. threat modelling, scenarios, metrics) and a willingness to be agnostic about the solution. Success will depend on avoiding the return of requirements by the backdoor. It is easy to imagine problem statements that amount to thinly-disguised specifications, with highly specific objectives that only one supplier is capable of meeting. It is likely that additional safeguards will be required to prevent drift of this kind.

Recommendations

1. Require an “off-the-shelf test” before every big project

Any project above £1 million should include a published scan of existing solutions already on the market. If 75% or more of the requirements can be met by something that already exists, the default should be to buy that product. Bespoke development should only be allowed if a minister issues a written direction.

Implementation pathway: The Secretary of State for Defence should direct the department to work with the Investment Approvals Committee (IAC) – which signs off business cases – to modify the Joint Service Publication 655 (Defence Investment Approvals). The policy should be updated within 30 days of ministerial instruction.

2. Freeze requirements after nine months

Once a project starts, the requirement list should be frozen within nine months. Any later change should require explicit Secretary of State sign-off. If a sponsoring Service still insists on adding requirements, the cost must come from its own budget, not central MOD funds.

Implementation pathway: The Secretary of State for Defence should issue a formal Direction to Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S) establishing a freeze within nine months on project requirements. The Direction should be issued on Day 1, with the freeze rule applying to all new programmes launched thereafter.

3. Create a “90-day fast lane” for proven kit

The MOD should establish a permanent “fast lane” for buying proven, off-the-shelf equipment within 90 days. This route would apply only to trusted NATO-standard or allied kit, with no modifications permitted.

Implementation pathway: The Secretary of State for Defence should instruct Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S) to create a dedicated Off-the-Shelf Fast Lane. Drafting responsibility would sit with the DG Commercial and DG Finance, who would set eligibility rules and spending thresholds. Purchases should be made using the “competitive flexible procedure” under the Procurement Act 2023, or where appropriate, direct awards or via existing frameworks. The first contracts should be processed within 90 days of the Direction, with the IAC reporting quarterly to the Defence Board on the number, value, and speed of Fast Lane buys.

2) Ending inter-service rivalry

A perennial obstacle to good defence procurement has been rivalry between the different services. This is ostensibly motivated by a scramble for scarce resources, but its roots lie in deeper cultural and institutional problems:

- Each service has a prestigious self-image and fears losing relevance. Losing a mission (e.g. carrier air power) or control over a domain is a threat. As a result, the services are incentivised to buy distinct, gold-plated platforms to ensure that they ‘own’ a domain, even when a joint solution might be cheaper and more effective.

- Promotion paths run inside single services, incentivising officers to become advocates for their service. While there are joint posts, many of them are perceived as career dead-ends.

- When MOD fails to set clear long-term priorities that acknowledge resource constraints, the services will default to maximising their slice.

In 2011, the government adopted a set of reforms proposed by Lord Levene, former Chief of Defence Procurement. The Levene Reforms devolved approximately 80% of the equipment and support budget to the frontline commands, assigning each chief a cash limit. It was hoped that this would allow the MOD to shrink its procurement-focused central headcount and prioritise big strategic questions over micromanaging budget line items. By weakening the centre and moving cash into competing silos, it amplified inter-service competition and skewed major procurement choices.

- The Army Air Corps and Royal Navy historically did not use the capable UK-designed Brimstone missile, because it was perceived as an RAF weapon, instead maintaining a parallel stock of US JAGM/Hellfire missiles for their helicopters.

- To protect carrier funding, the Navy accepted cuts to escorts, early warning, and support ships, but had no control over fast-jet procurement, which remained with the RAF. The RAF retired Harriers in 2010 to preserve Tornado, leaving the new carriers without jets. HMS Queen Elizabeth was commissioned in 2017, but her first deployment with jets didn’t occur until 2021, the majority of which were supplied by the US Marine Corps. The UK still lacks enough aircraft to field a full 36-jet carrier air wing with its own fleet.

- The UK switched F-35 variants twice – first from the short takeoff B to the longer-range C – wasting years and hundreds of millions of pounds. UK carriers use a ‘ski jump’ ramp instead of catapults to launch aircraft – this limits them to short-take off and landing jets like the F-35B. But the RAF advocated for the F-35C, so they could control the fleet. After the cost of modifying the carriers to accommodate the C escalated, the government switched back to the B. The RAF then managed to lobby successfully to convert a portion of the F35-B order into F-35As, which are not suitable for sea operations at all.

This kind of eccentricity would be more understandable in a significantly larger and better-funded military, but maintaining parallel fleets or missile lines is unjustifiable when personnel numbers sit below 150,000 and MOD struggles to make ends meet.

To its credit, the government has recognised this. In 2025, it ended the Levene Reforms and created the new position of a National Armaments Director (NAD), responsible for overseeing the UK’s defence industrial strategy. This is an important step forward, as one official now controls the more than £30 billion ‘invest’, which controls everything that buys or upgrades kit, infrastructure, R&D, or digital.

However, there are certain points quirks of the system that prevent the NAD role from reaching its full potential:

- The position is limited to five years and can only be extended to nine years in exceptional circumstances. This is shorter than the procurement cycle for most major platforms.

- The NAD only has a small central team to work with, and will remain reliant on forecasts and costings provided by the services.

- The NAD has to work ‘in partnership’ with service chiefs, who retain political and institutional clout, and have the power to escalate to ministers.

- The NAD has no power over ‘readiness’ spending. When a service hits an in-year cash squeeze it can quietly cut spare parts or training hours from its ‘readiness’ budget. That keeps the books balanced, but risks equipment being unavailable next year. This hollows out readiness and undermines joint planning.

The capability portfolios outlined in the segmented procurement model offer a route forward, but these risk becoming another battleground between the services. It will be vital to ensure that they do not become three parallel wishlists and that the different procurement lanes are not gamed to benefit individual platforms at the expense of rapid, joint tech.

As well as pushing centralising spending in the hands of the NAD, there is an argument for pushing some spending authorisation below frontline commands. Brigade commanders have some discretionary spending power, but this is relatively limited. There is a case for expanding this authority, as in Germany, to make it easier for them to buy equipment off-the-shelf. As they are a step removed from inter-service rivalry and more motivated by urgent operational requirements, this discretionary spending is less likely to be politicised and could be a method of getting critical capabilities (e.g. cheap drones) to the frontline significantly faster.

Recommendations

1. Extend the NAD’s tenure to match programme timelines.

Most major defence programmes run well over a decade, yet the NAD role is capped at five years (nine in exceptional cases). This short horizon undermines continuity and allows services to “wait out” an unwelcome NAD, resuming old habits once leadership changes. Extending the tenure would align authority with programme timelines and make one official truly accountable.

Implementation pathway: The Cabinet Office and MOD Permanent Secretary should amend the NAD’s terms of appointment, raising the minimum to ten years (renewable with ministerial consent). As the post remains unfilled, they should aim to do this before the first full-time NAD is in place.

2. Establish an independent cost analysis unit (UK CAPE)

The services consistently underestimate costs and oversell benefits, making it hard for the NAD to challenge gold-plated projects. A UK version of the US Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) would provide independent analysis on programme costs, technical risks, and alternatives.

Implementation pathway: The MOD Permanent Secretary, in partnership with the Treasury, should establish a 50-strong team of independent analysts drawn from academia and industry, explicitly excluding ex-military to avoid biasing towards the house view. It should be housed within MOD but report directly to the NAD. Initial staffing and funding should be agreed at the next Spending Review.

3. Give the NAD a concept-stage veto with parliamentary transparency

The NAD currently has no formal power to block wasteful projects before they gather momentum. A statutory veto at the Concept Stage would allow the NAD to reject gold-plated or duplicative proposals, with ministers able to override only through a public written direction laid before Parliament.

Implementation pathway: The Cabinet Office should bring forward an amendment to the Procurement Act 2023 granting the NAD this authority. The change should be enacted in the next legislative session, with guidance to the IAC Secretariat on applying the veto process.

4. Publish a quarterly readiness ledger signed by the NAD

Services often raid readiness budgets to balance their books, cutting spares and training while protecting prestige projects. This hollows out capability and undermines joint planning. A transparent quarterly ledger would expose these trade-offs in real time.

Implementation pathway: The NAD should be required to publish a traffic-light report each quarter covering fleet hours, spares, and maintenance backlogs for each Service. The IAC Secretariat would compile the data, and any amber or red rating would trigger a mandatory rebalancing plan presented to the Defence Board within 30 days.

5. Increase brigade-level discretionary spending authority

At the other end of the chain, too little spending power sits with frontline commanders. Brigade commanders are best placed to see urgent needs (drones, radios, protective kit) but their discretionary budgets are too small to make meaningful purchases. Expanding their authority, as in Germany, would allow rapid off-the-shelf buys for pressing operational requirements.

Implementation pathway: The MOD Accounting Officer should amend delegated financial authorities to raise brigade-level discretionary ceilings to at least £5–10 million annually, limited to non-developmental, off-the-shelf kit. Compliance and audits would sit with the Government Internal Audit Agency.

3) Ending short-termism and systemic optimism bias

Alongside persistent rivalry, the other persistent enemy of good procurement and planning is MOD’s systematic tendency towards over-optimism. This manifests in the persistent underestimation of cost, time, and technical risk at the outset of major projects – and is intimately tied to the overspecification problem covered above.

Often referred to as a ‘culture of optimism’ in the many post-mortems of failed procurement, this is really a structural feature of how projects are proposed, assessed, and approved. MOD operates in a system where long-term capital programmes are governed by short-term cash limits, decision-makers are rewarded for getting projects approved rather than delivered, and only a handful of overrunning projects have ever been cancelled.

Most capital projects are funded through Treasury’s Departmental Expenditure Limits, which operate on an annual cycle. Funding is released in fixed yearly tranches and MOD project teams cannot reliably bank underspends for future years, with any surplus netted off their budget in the following cycle.

This is a poor way of funding multi-billion pound, multi-year defence programmes. It incentivises programme teams to shape numbers to fit inside their allocation, on the basis that the money will be found later. It also sometimes leads programmes to be stretched out longer than needed to meet annual budgets. For example, MOD delayed its purchase of 16 US Protector UAVs in 2021 by two years to allow the department to claim in-year savings. This, along with specification changes, contributed to the eventual cost jumping by over 40%.

Additionally, Senior Responsible Owners are reshuffled every two to three years. This means that they rarely see a project from beginning to end, and thus are not held to account for unrealistic projections. This is entrenched through MOD’s use of P50 confidence levels on cost and schedule, which means that numbers are set on the assumption that there is a 50-50 chance they are incorrect.

As Bernard Gray’s 2009 review of defence acquisition warned, this creates a ‘game theory’ dynamic, where each of the services is incentivised to pitch the best possible solution at the lowest plausible price. In essence: optimism meets overspecification meets inter-service rivalry:

- The independent review into the Ajax programme found evidence of “unsubstantiated optimism” across the programme, with critical risks understated and inconvenient evidence under-reported. To save on schedule, demonstration and manufacture of the immature technology described above were run in parallel.

- In 2017, steel cutting for the Type 26 frigate started before the design had been finalised. In 2022, the Defence Secretary had to acknowledge a £233 million cost increase and delay of at least a year due to design maturity issues. The gearbox was delivered so late that the hull of the HMS Glasgow had to be cut open so it could be inserted by crane.

- The cancelled Nimrod Maritime Reconnaissance overran for seven years before being cancelled, after a planned new wing design did not fit a 1970s fuselage design. While industry underestimated the design challenge, a parliamentary report found that MOD accepted forecasts that “lacked depth and reality”.

Recommendations

- Adopt P75 cost and schedule baselines for all projects over £20 million

Set budgets and timelines so there’s at least a 75% chance of hitting them (P75), and include a clearly ring-fenced contingency to cover known risks. Any exception should require a formal ministerial written direction.

Implementation pathway: The MOD’s Investment Approvals Committee (IAC) should propose updates to JSP 655 (Defence Investment Approvals) to (i) require P75 baselines and simple probability-based cost/schedule analysis and benchmarking against past, similar projects. Existing programmes over £500 million should be reset to P75 at their next decision point.

- Create automatic multi-year capital flexibility for the Equipment Plan

Give the MOD an automatic right to carry money forward or bring it forward across financial years for equipment projects – without case-by-case Treasury approval and without docking the next year’s budget.

Implementation pathway: HM Treasury should update the Consolidated Budgeting Guidance to grant the MOD the automatic right to move money between financial years, and issue an updated delegation letter to the department.

- Keep SROs in post for a minimum of five years with delivery-linked incentives

Senior Responsible Owners (SROs) for major programmes should serve at least five years.

Implementation pathway: The MOD Permanent Secretary should set a five-year minimum SRO tenure for all new major projects (and align existing ones at their next gate). Civil Service HR, DE&S and the Front Line Commands should adjust postings to match programme phases. The IAC should not approve cases without an SRO whose planned tenure covers the next five years unless the Secretary of State approves an exception.

4) Restoring sovereign capability

In the context of defence procurement, sovereignty is often conflated with self-sufficiency or protectionism. The goal should be neither to domestically produce everything nor to procure only domestically: both of these strategies would lead to low-quality, poor value and uncompetitive capabilities.

Instead, sovereignty is about a nation’s agency and capacity to control its destiny. This requires wealth, a strong view about the direction of travel, and the institutional capability to make good choices. In effect, when it comes to defence suppliers, governments face a ‘sovereignty trilemma’ between speed, capability and resilience (in the form of prioritising domestic jobs and supply chains).

If a non-UK defence-tech company creates a best-in-class capability, it may very well be in Britain’s sovereign interest to procure and deploy it for strategic advantage. Similarly, it is not always in Britain’s sovereign interest to procure only from domestic companies if they cannot deliver a) timely or b) competitive capabilities if other international suppliers can. Defence procurement exists for militaries to acquire the capabilities they need, when they need them, not simply to prop up jobs.

The catch, of course, is that choosing the expedient or cost-minimising option repeatedly may erode the domestic military-industrial base. The cost of this dependence is hidden, until it’s not: can your military keep fighting even if your allies decide they don’t want to help? Do you have the negotiating leverage to access the military capabilities you need on good terms? Can you keep building and deploying under pressure, when your allies are busy and adversaries are interfering? When global markets are open and supply chains are predictable, cost-minimisation looks reasonable. But as geopolitical rivalries harden, nations wield their productive power as an instrument of statecraft and supply chains become contested, suddenly you can’t mobilise at pace and lack strategic autonomy.

This is the moment we find ourselves in today.

The UK’s stocks of critical equipment are depleted and restarting production is challenging. British industrial users pay electricity prices that are 300% higher than in the US, 160% higher than in Korea, and 46% higher than the median country in the International Energy database.

In November 2022, the government sent a letter to defence primes announcing its intention to resume purchasing artillery shells, but the contract negotiations took nine months, due to the lack of a working production line and concern about how it would be funded.

The war in Ukraine and the Trump Administration’s unpredictable foreign policy is forcing European countries to face up to their dependence on the US for a range of critical capabilities, including ballistic missile defence and anti-submarine warfare.

UK defence strategies have repeatedly paid lip service to the idea of preserving the UK sovereign capabilities in core areas, but there has been a consistent mismatch between rhetoric and reality. This has been driven by two forces.

First, a lack of consistent orders. Defence manufacturing is a capital intensive and low margin business with a limited pool of customers. Without a steady drumbeat of orders, it atrophies:

- BAE Systems shut its Woodford site in 2011 after the cancellation of the Nimrod MRA4, and ended aircraft manufacturing at Brough in 2020 following the wind-down of Hawk trainer production.

- Aerospace and defence supplier Cobham was sold to US private equity in 2020 after multiple profit warnings linked to shrinking UK orders.

- Advent, the firm that acquired Cobham, then acquired Ultra Electronics, which supplied submarine hunting technology to the Royal Navy, along with the control systems for nuclear reactors on the UK’s submarine fleet.

- A few months later, US firm Parker Hannifin acquired Meggitt, a FTSE-listed engineering group and another long-standing MOD supplier.

With a handful of exceptions, domestic UK capabilities have been eroded:

Capability | Status |

|---|---|

Maritime patrol aircraft | UK-built Nimrod MRA4 scrapped in favour of the US-built Boeing P-8A Poseidon |

Attack helicopters | Apache helicopters used to be assembled by Westland in Yeovil, but this process was cut in favour of direct purchasing |

Logistics trucks | British manufacturers like Bedford and Foden are gone. Today’s fleet is manufactured by Rheinmetall MAN, a German joint-venture. Core manufacture happens in Germany, with only final assembly in the UK |

Artillery | With the retirement of the UK-made AS90, the UK has bought Swedish-made Archer guns and the German RCH-155 |

Drones | After the failure of Watchkeeper, the UK moved to the US-built MQ-9 Reaper and now US-built Protector RG Mk1 |

Diesel-electric submarines | The UK last built these in the 1990s, before exiting the conventional submarine business. Any future orders would need to be imported. |

Small arms | Domestic small-arms factories (e.g. RSAF Enfield and ROF Nottingham) are now closed. The standard service pistol since 2013 is the Austrian Glock 17, procured off-the-shelf. |

Second, the UK’s procurement framework has not formally preferenced British companies since privatization in the 1980s and 1990s. This is a political, rather than a legal choice. Both the World Trade Organisation’s Agreement on Government Procurement and European state aid rules contain national security exemptions. But in 2012, the Coalition government stated that: “Wherever possible, we will seek to fulfil the UK’s defence and security requirements through open competition in the domestic and global market, buying off-the-shelf where appropriate.” However, the UK has maintained a handful of exemptions to this rule, most notably for Royal Navy warships, although MOD loosened this rule to allow the UK to buy auxiliary ships from overseas.

Many of our closest allies are considerably more protectionist. The Buy American Act requires the US government to default to buying from American suppliers. The Biden Administration actually increased the domestic content threshold for end products from 55% to 75%. The French government sets requirements in close collaboration with domestic industry and the government continues to hold significant ownership stakes in French defence companies.

In 2021, the UK changed tack, introducing a weighting for social value and to “encourage and support defence suppliers, whether headquartered here or overseas, to consider carefully what can be sourced from within the UK”. This criteria is currently weighted at a minimum of 10%, but it can be increased where market maturity allows.

The 10% weighting, however, is primarily focused on net zero (itself a cost driver), well-being, and equal opportunity, rather than local economic impact. These criteria are easy for multinationals to game and are not relevant considerations for defence procurement.

The Procurement Act 2023 has also created more flexibility. For example, as part of the Corvus programme, a £130 million competition to replace Watchkeeper, companies were asked in the early downselection about how much of their solution would be designed, manufactured, and assembled in the UK. Any company without a clear UK entity was also barred from bidding.

While these are promising steps, it is important to be clear-eyed about what is possible.

With sustained, multi-year orders, there are some clear areas of strength that could scale with relatively light investment. BAE is already gearing up to expand munitions production, while Chemring is well-placed in countermeasures and energetics. UK-based and UK-owned companies still have capabilities when it comes to lighter armoured vehicles, with Supacat and Babcock teaming up to produce the Jackal 3. With more sustained investment, it is possible to imagine the production of heavier armoured vehicles returning to Britain, reducing MOD’s dependence on Germany for manufacturing.

At the same time, there are some areas where it is prohibitively expensive to restore sovereign capability and attempts to do so would likely produce expensive equipment and fail to fuel the creation of an export market. The UK can assemble helicopters, but manufacturing capability is unlikely to return. Any future British-made drones look set to be dependent on Chinese components, unless the UK is prepared to invest the billions required to fully localise motors, batteries, sensors, and printed circuit boards.

Sovereign capability, of course, does not have to mean autarky. Some of the rare success stories in UK defence procurement have come from multinational collaborations, such as the complex weapons partnership with multi-national missile systems producer MBDA. Owned by Airbus, Leonardo, and BAE Systems, MBDA has delivered quickly thanks to consistent orders and a gradual reduction in the use of bespoke components. MBDA signed a multi-billion pound export deal with Poland in November 2023 and recently announced plans to expand its Bolton site.

Moreover, overly-blunt approaches to sovereignty risk missing nuance or deterring investment. For example, a UK-domiciled company that does not employ a single British engineer and uses components entirely manufactured overseas is ‘British’ in one sense, but not in a strategically relevant way. Similarly, driving either European innovators (like Helsing or Tekever) or US primes that act as significant domestic employers out of the UK altogether will not strengthen the UK’s position. Any real measure of domestic preference will need to account for IP, supply chain, staff, and the nature of the work performed in the UK.

Recommendations

- Disapply the current set of social value criteria

The current set of social value criteria reward symbolic or performative measures that benefit large incumbents, while adding an undue burden on new entrants. The choice of measure does little to strengthen UK sovereignty.

Implementation pathway: MOD is currently not mandated to include social value on defence and security contracts and this is left to individual project teams to decide. The Secretary of State should direct the DG Commercial and Industry and the CEO of DE&S that these should be set aside in all such procurements.

- Introduce a consistent UK prosperity weighting

While MOD is beginning to screen companies bidding for some contracts on their economic contribution and ties to the UK, this is currently happening on an ad hoc basis. This kind of screening is not necessary for low-level commodity goods or capabilities that the UK has little hope of plausibly onshoring, but for contracts in the areas identified above, MOD should apply a consistent UK weighting. For example, in these categories, there could be a 10% weighting for price and 90% for UK prosperity and manufacturing. This 90% could be split across employment, IP, supply chain, and category of work (e.g. assembly, manufacturing, maintenance, support functions).

Implementation pathway: The Procurement Act 2023 likely gives MOD the power it needs to implement these rules. The Secretary of State should direct the NAD, the CEO of DE&S, and the DG Commercial and Industry to draw up a set of criteria and how they should be judged. If, in consultation with legal counsel, they conclude that legislative changes are required to introduce this system, these should be spelled out in a detailed letter to the Secretary of State within 60 days. If not, the criteria for UK prosperity and manufacturing should be published within 90 days.

- Professionalise defence procurement to actively shape our domestic industrial base and supply chain

The world’s largest companies take the supply-chain management function incredibly seriously: for example, Apple invested billions in China not only to create, develop and upgrade its supplier base, but also to ensure competition in the supply chain and reduce any one supplier’s leverage or pricing power.

A sovereign defence procurement system should similarly combine spend controls, data intelligence and procurement professionalisation to empower Britain to improve its decision making and support sovereignty – trading off speed, capability and resilience – as circumstances demand.

Implementation pathway: Launch a recruitment drive for experienced procurement leads from firms with complex, global supply chains, bringing new talent into MoD who are not wedded to existing projects or procurement efforts. Build a combined view of existing defence procurement data with data from the British Business Bank, HMRC, UKRI and Innovate UK on the UK’s defence-industrial ecosystem to identify areas of potential strength.

5) Partnering with innovators

Rhetoric versus reality

Despite repeated pledges by MOD to diversify its pool of suppliers, it has failed to do so. The current top 10 defence suppliers receive 38.7% of MOD expenditure, a drop of 0.1 percentage points versus 10 years ago.

While start-ups have to fight for every contract, many of the largest companies receive significant orders through single-source procurement, where MOD deems that only one appropriate supplier exists.

Supplier | Expenditure (£ million) | Percentage competitive (%) |

|---|---|---|

BAE Systems | 5,717 | 10 |

Babcock International | 2,749 | 44 |

Rolls-Royce | 1,204 | 1 |

QinetiQ | 1,174 | 45 |

Airbus | 931 | 29 |

Leonardo | 704 | 8 |

Leidos | 668 | 99 |

Thales | 602 | 25 |

Serco | 596 | 80 |

Boeing | 582 | 9 |

Our inability to work with disruptors is keeping British defence capabilities behind the frontier. The conflict in Ukraine is showing us the importance of technology like drones, GPS-denied navigation, electronic warfare, autonomous surveillance and sensors. Ukrainian forces have complained that the training they receive from NATO does not reflect the realities of the modern battlefield.

The war in Ukraine shows us that the UK is woefully underprepared for the next generation of warfare. For example, a recent select committee report warned of “a gap between rhetoric and reality” in the Ministry of Defence’s adoption of AI, with “few examples of Defence AI applications making it beyond small-scale experimentation and actually being adopted by the Armed Forces”.

MOD has a track record of making big commitments on innovation and then failing to deliver. For example, the Strategic Defence Review endorsed spending over £1 billion on a planned ‘Digital Targeting Web’, a capability that would better connect weapons systems and increase the speed at which battlefield decisions could be made. Based on conversations with MOD insiders as part of this report, it has become apparent that MOD has not allocated any money to the project this year and plans to spend less than £25 million on it in 2026.

The problem is compounded by low levels of in-house technical understanding within MOD, which means that mundane capabilities presented by suppliers are treated as cutting-edge. For example, the Defence Artificial Intelligence Strategy, which has not been updated since 2022, lists edge AI and object detection in satellite imagery as next generation capabilities, when both have been available off the shelf for quite some time. The Defence Artificial Intelligence Centre, which started operations in 2022, is a small, underpowered team that is focused on AI in MOD HQ.

Even if MOD knew how to procure frontier defence technology, the primes likely wouldn’t be the best placed to fulfil orders because they aren’t set up to win the software race. Defence primes, whose heritage is grounded in traditional hardware, do not attract or incentivise top AI talent and prioritise share buybacks and dividends over R&D investment. They are the main beneficiaries of the current system of slow, overspecified procurement, and many of them are hardware-first companies belatedly taking an interest in AI.

The primes will continue to play an important role in certain sectors: venture-backed start-ups are clearly not the right businesses to mass produce armoured vehicles or ammunition. But the primes are ill-suited, for example, to producing cheap drones guided by AI-first software that will need rapid adaptation as enemy electronic warfare adapts. Even if we wanted the primes to produce the hardware and start-ups to provide the AI, the hardware and software components of contracts are bundled by default. This can lead to perverse outcomes on individual projects. For example, Asgard, the successor to the Watchkeeper drone, was primarily shaped by hardware requirements, despite autonomy being central to the capability. This discouraged some companies with deep AI expertise from bidding at all.

This gap between rhetoric and reality is stark in the 10% novel technologies ringfence. While there are formal criteria for what constitutes ‘novel’ technology, these are unpublished and not followed in practice. It is widely believed that the ringfenced portion is being looted to pay for existing programmes that stretch the definition of ‘novelty’. For example, funds from the ringfence to pay for the F-35 programme, a fighter jet that first came into service a decade ago and which the UK has been committed to purchasing since 2012.

Lack of pace

Unfortunately, challengers are locked out by design. There remains essentially little meaningful market for UK defence start ups. They are shut out from major procurement, because timelines are slow, taking an average of 6.5 years for a contract of £20 million or more. Culturally, MOD procurement officers prefer the ‘safety’ of working with established suppliers, even where their record of delivery is patchy, and have no incentive to take the ‘risk’ of working with an early-stage company. Speed, which is vital to innovators, is not a factor in the business case process. This means that a company that could deliver a ‘good enough’ solution that meets an urgent need could lose out to a company promising a more elegant version on a significantly slower timeline.

Not only can many early-stage companies simply not last a 6.5 year procurement cycle, the terms are crucial. MOD is often reluctant to pay upfront for capabilities. This means that companies can see revenue chopped up over several years. For a cash-rich defence prime producing an armoured vehicle, this is simply an accounting question. However, for a challenger, this can be an existential question.

There are various MOD bodies whose official task is identifying innovation and pulling it through to the frontline, but their record is patchy. The Defence and Security Accelerator, for example, was set up as a body for new innovation, but awards the plurality of its contracts to defence primes. The new entrants that do win one-off grants rarely go on to win significant contracts outside the accelerator – this means building a business on small one-off projects that provide unpredictable revenue, in the hope of acquisition by an incumbent.

MOD and government’s response to these failures historically has not been to reexamine its approach, it has instead been to berate private investors. The previous government attacked investors directly, while this one continues to argue about ESG criteria with pension funds. This approach ignores the simple reality that challenger defence companies will never exist if there is no market for them to sell their products to.

Part of the problem is that MOD draws no practical distinction between ‘start-ups’ and classic small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). A classic SME can serve as a regional employer or subcontractor to a defence prime, but a venture-backed start-up has a different return profile. Investors in venture funds are paying high fees and surrendering a decade of liquidity, so they expect a significant return. This means that every start-up a VC invests needs at least the possibility of becoming a billion pound company. If the biggest aspiration these companies can have is to act as a subcontractor to an incumbent, they are unlikely to ever reach this milestone.

Bureaucratic hurdles

Alongside cultural hostility, innovators have to contend with a number of bureaucratic hurdles:

- Many procurement decisions are made via framework contracts. These are umbrella contracts between the government and a number of suppliers, which fix pricing, scope, and conditions for buying goods or services in future without committing to specific quantities or timing upfront. This allows MOD to buy directly and relatively quickly from a company on the framework, but those not on the framework are ineligible. MOD periodically reopens frameworks to allow new entrants, but the window can remain shut for years at a time.

- To work on classified projects, a company needs clearances, but without obtaining work before hand, it can be hard to obtain the clearance. This often leads to start-ups engaging in expensive subcontracting workarounds or hiring team members with clearances from previous roles.

- To hold classified material, a company needs to comply with the guidance in the Facility Security Clearance Policy and Guidance. Much of this is cumbersome and expensive for early stage businesses (e.g. special doors, sweeps for bugs). While the MOD does provide compliant facilities, they are frequently in remote locations.

- Securing permission to test equipment like drones can be slow for new entrants, who are deprioritised by undercapacity regulators. This means that individual tests can be months apart, significantly slowing iteration cycles. It leaves start-ups in a Catch 22: unable to test without a contract, unable to get a contract without testing.

The ideal end-state for procuring more advanced capabilities would be abandoning the current paper-driven requirements system and moving to a set of multi-round field trials for a predetermined set of priority capabilities. Such trials could potentially be run by the UK Defence Innovation Agency that the Centre of British Progress has previously proposed. This is both a more rational way of testing potential equipment, especially in a world where MOD has moved away from over-specification, and would significantly level the playing field in favour of new entrants. But this is unlikely to happen in the short-term, so there may be a case for the more targeted use of single-source procurement powers to upgrade the UK’s arsenal.

The creation of UK Defence Innovation offers the possibility of partially meeting this goal. The challenge will be to prevent it from facing the same face as other innovation units. So far, there is nothing to compel the services to adopt the specific tools or systems that UKDI backs. Promising projects may stall when budgets tighten or when major platform programmes crowd out newer options. Its funding is described as protected, but in practice it will sit in the same environment as every other budget line and may be used to plug gaps elsewhere.

There are also changes beyond just contracting that would disproportionately help innovators, while creating a functioning market for everybody else. One of the biggest sources of delay is the business case approvals process. As well as being deeply obscure, even to many insiders, the process contains a significant number of veto points. Even the renewal of an existing contract, according to former MOD insiders and industry sources, can involve 9–12 months of discussion and approval from dozens of officials. The Chief of the Defence Staff acknowledged that “we have prioritised cost and perfection over time” in a recent speech, noting that “we must ensure companies can make money in this new model”. Any spend over £50,000 now requires sign-off from the Secretary of State, after the government reduced the limit from £2 million last year.

One of the challenges is the specificity involved in the process. Project teams must draft proposals, designs, and requirements in very detailed, prescriptive terms before they can progress, often in exhaustive documentation. Teams must define exactly what will be built, how it will meet capability requirements, and how every risk will be mitigated, even when the underlying design remains uncertain. This is not only time-consuming, but prevents adaptive or iterative development.

The system is at its most effective when it is able to circumvent as much of this as possible. For example, Task Force Kindred, which secured the supply of materials for the Ukrainian armed forces, delegated approvals and assurance as far down the chain as possible. The business case, which secured money directly from the Treasury, was drafted broadly, giving project teams scope to adjust. As a result, Kindred is a rare example of a MOD initiative to be praised by the National Audit Office.

Recommendations

1. Add time as a factor in the business case process

Time to delivery (as opposed to merely the ability to meet an agreed timeline) should be a factor in the business case process.

Implementation pathway: The Secretary of State and Investment Approvals Committee should state that ‘time to first use’ is now a core criterion in procurement decisions. The ‘time to first use’ would be picked from a set of bands (e.g. 0–6 months, 6–18 months, 18–36 months, and 36+ months) and the choice of band. Every business case would justify the choice of band and present a ‘fastest credible option’ and, if necessary, an explanation for why that option was not chosen.

2. Focus accelerators on genuine start-ups

MOD should reserve accelerator funding for early-stage companies, while moving post-Series B firms into mainstream procurement.

Implementation pathway: The Secretary of State should issue updated terms of reference for the Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA) and similar schemes, barring companies beyond Series B funding rounds from applying for innovation grants. Those firms should instead be directed into DE&S competitions or framework contracts. DASA should be brought fully in-house.

3. Unbundle hardware and software in major contracts

Implementation pathway: The DG Commercial should issue a direction requiring all contracts worth more than £10 million to be designated hardware-first, software-first, or hybrid, unless the NAD agrees to an exemption. Where contracts are hybrid, the hardware, software, and integration should be completely unbundled. Where they are hardware or software-first, this component should be prioritised in both the requirements and choice of supplier.

This ensures software companies can compete for the software layer without being shut out by primes that dominate hardware. It brings in specialist expertise, improves quality, and reduces the risk of underwhelming “bolt-on” software from primes.

6. Allow initial batch production outside competition rules

At present, the MOD can only bypass competitive tendering in cases of “extreme and unavoidable urgency” under the Procurement Act 2023. That bar is so high that it effectively excludes early-stage firms with promising technology. The result is a Catch-22: MOD says it cannot single-source small production runs from a start-up to test their kit in the field, but without that step, start-ups can’t prove they are competitive at scale.

Implementation pathway: The Cabinet Office should bring forward an amendment to the Procurement Act 2023 creating a new exemption for “initial batch procurement,” capped at a defined contract value (e.g. £50 million) and time limit (18 months). MOD would then be required to run a competitive process for follow-on buys.

7. Enforce the criteria for the 10% ring fence

Currently the criteria for the 10% novel technologies ringfence have not been published and are being ignored in practice. This undermines a core recommendation from the Strategic Defence Review.

Implementation pathway: The Secretary of State should direct the department to publish the guidance stating what constitutes a ‘novel technology’. For any programme that sits outside this scope, the NAD should issue a public notice stating what the money is being used to fund, alongside a timeline stating when MOD will refund the ringfence.

8. Allow upfront payment in full for certain contracts

To attract top-tier challengers to the UK and ensure long procurement cycles do not become an obstacle for innovative businesses, allow early payment in full for priority capabilities.

Implementation pathway: The Secretary of State should secure the necessary derogation from the Treasury to allow payment in full upfront for certain contracts. MOD should issue a Commercial Policy Statement stating that either projects selected by UKDI or projects in the rapid lane under the segmented procurement model should qualify.

A word of caution: procurement reform is not a silver bullet

Reforming defence procurement is necessary to upgrade our capabilities and support a domestic industry, but it will not be sufficient. Solving procurement will not provide UK defence with strategic coherence, resolve chronic personnel gaps, or single-handedly revive the UK’s defence-industrial base. Even the best-designed procurement system will only operate if defence receives sustained investment and industry consistent demand signals.

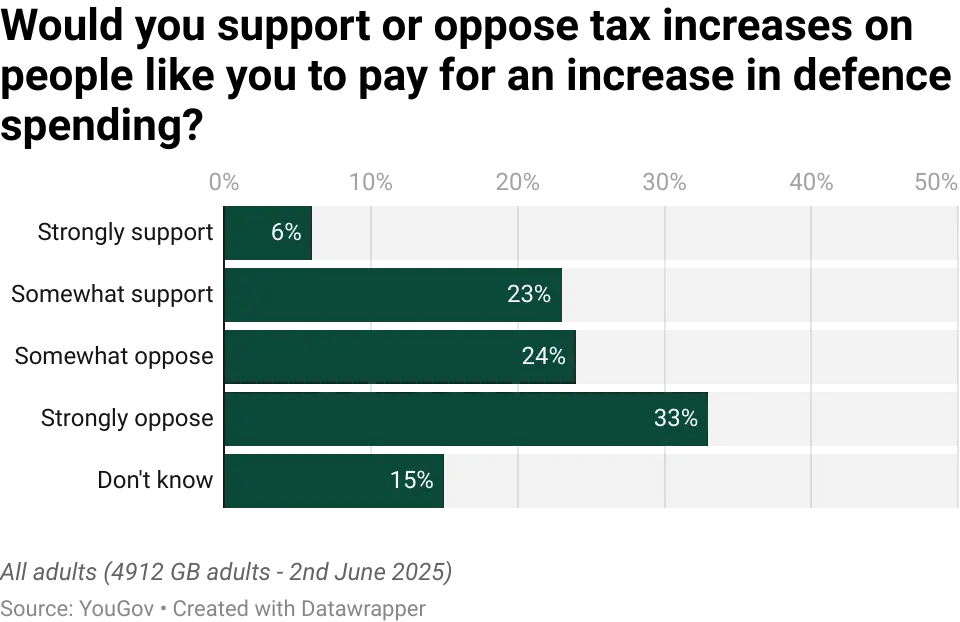

While the government has signalled it will increase spending on defence to as much as 3% of GDP by the next parliament, planned increases barely cover the UK’s existing commitments. Polling has repeatedly shown that after years of stagnating living standards, there is understandably little public appetite for either tax rises or spending cuts to pay for defence.

This should force two separate conversations.

First, a long-needed re-evaluation of the role of UK defence. The terms of reference for the Strategic Defence Review meant that the authors, while independent, had relatively little scope to challenge the official assumption that the UK defence both can and should extend across the homeland, the Euro-Atlantic, and multiple other global theatres. The UK remains committed to being present everywhere at the expense of being resourced anywhere.

A more realistic set of assumptions about where the UK’s military might be deployed and whom it would fight alongside, might lead to a more manageable set of procurement asks. This would allow the UK to double down on capabilities that our allies find harder to produce, rather than creating a ‘shop front military’, which in the words of Retired Air Marshal Edward Stringer, “can excel on displays and exercises … but when you go behind the facade, there’s precious little on the shelves and no production line behind it”.

Second, there should be no illusions about how easy a task like reindustrialisation will be. Consistent, long-term orders are one thing, but in the heyday of the UK arms industry, the UK was energy self-sufficient and the world’s biggest exporter of coal. A sclerotic planning system, tight labour regulation, and expensive energy are not promising foundations on which to rebuild. Serious work to improve resilience may start with well-targeted spending and faster contracting, but it will fail if it ends there.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]