Table of Contents

- 1. Foreword

- 2. Top lines

- 3. Background

- 4. Authors

Foreword

By Yuan Yang MP

The Prime Minister has said that “every minute we focus on anything other than cost of living is a wasted minute”. The Centre for British Progress and the Living Standards Coalition have come together to gather ideas to get food inflation under control.

Between July 2020 and July 2025, food prices increased by 37%, significantly higher than overall UK inflation. Since 2023, it has also been persistently higher than comparable European economies, due to Brexit trade frictions and Britain’s higher energy costs.

Food costs, especially for low-income households, are a significant expenditure. Food inflation is also politically important because of the salience of prices of goods like meat, milk and meal deals. It anchors people’s impressions of the state of the economy. Successful social democratic parties across the world are running campaigns that focus on bringing down the cost of the weekly shop.

There are broader macroeconomic reasons to focus on food inflation. For the Bank of England to continue cutting interest rates further and at pace, the government must convince the Monetary Policy Committee that the Treasury’s interventions on prices can effectively tackle the sectors that have been driving a high overall inflation rate – and insulate us from future supply-side shocks.

In the UK, some have argued that there is little the government can do on food inflation. Food prices are already very competitive compared to other countries in the OECD and therefore options for supply-side interventions are limited.

Rather than accepting defeat, we believe the debate over food prices deserves revival. This briefing attempts to identify meaningful levers for the government to pull.

There may be ways to improve market structure and drive more competition, and the CMA must remain empowered to continue to look into the supermarket sector as a whole, and individual components of it like infant milk formula. But even if the market is already operating fairly efficiently, we should instead look at how we can reduce costs and barriers for supermarkets and corner shops, and how these savings can be passed on to consumers.

The ideas in this report seek to be both practical and fiscally neutral. Together these measures could reduce food prices by over 6%. I hope they spark debate over this critical part of the everyday economy.

Top lines

- Food prices remain high. Although inflation is falling, many households continue to feel the effects of increases over the last few years. Combined with low wage growth, this has a severe impact on living standards, and voters’ assessment of the Government.

- Supermarkets have thin margins. There is little to be squeezed from supermarket profits. Instead we must find ways to reduce costs across the board, and help people access lower-cost supermarkets and the best deals, such as multi-buy and loyalty discounts.

- Input costs are hard to tackle. Aside from higher food wholesale prices, supermarkets face higher energy and labour costs. The Government’s options here are limited: VAT on energy is already applied at the reduced rate of 5%, and more fundamental reforms take time. Reducing wages (e.g. through the national minimum wage) would be counterproductive for living standards.

- However, there are two meaningful levers the Government could pull:

- 1. Closer alignment with the EU: negotiating and agreeing a deal on SPS, plus some customs arrangement, could lower food prices by 3-6% for EU food imports, depending on the level of alignment.

- 2. Reform planning to increase supermarket competition: current planning constraints benefit incumbents and limit the availability of lower-cost shops. Previous competition action that enabled the rise of Lidl and Aldi created estimated welfare gains of 3.5% on certain basic products. The Government could go further and introduce a permitted development right (PDR) for supermarkets, which would make it easier to open new branches in underserved areas..

- Together these measures could reduce food prices by over 6%, particularly in areas that currently lack low-cost supermarkets due to planning restrictions.

Background

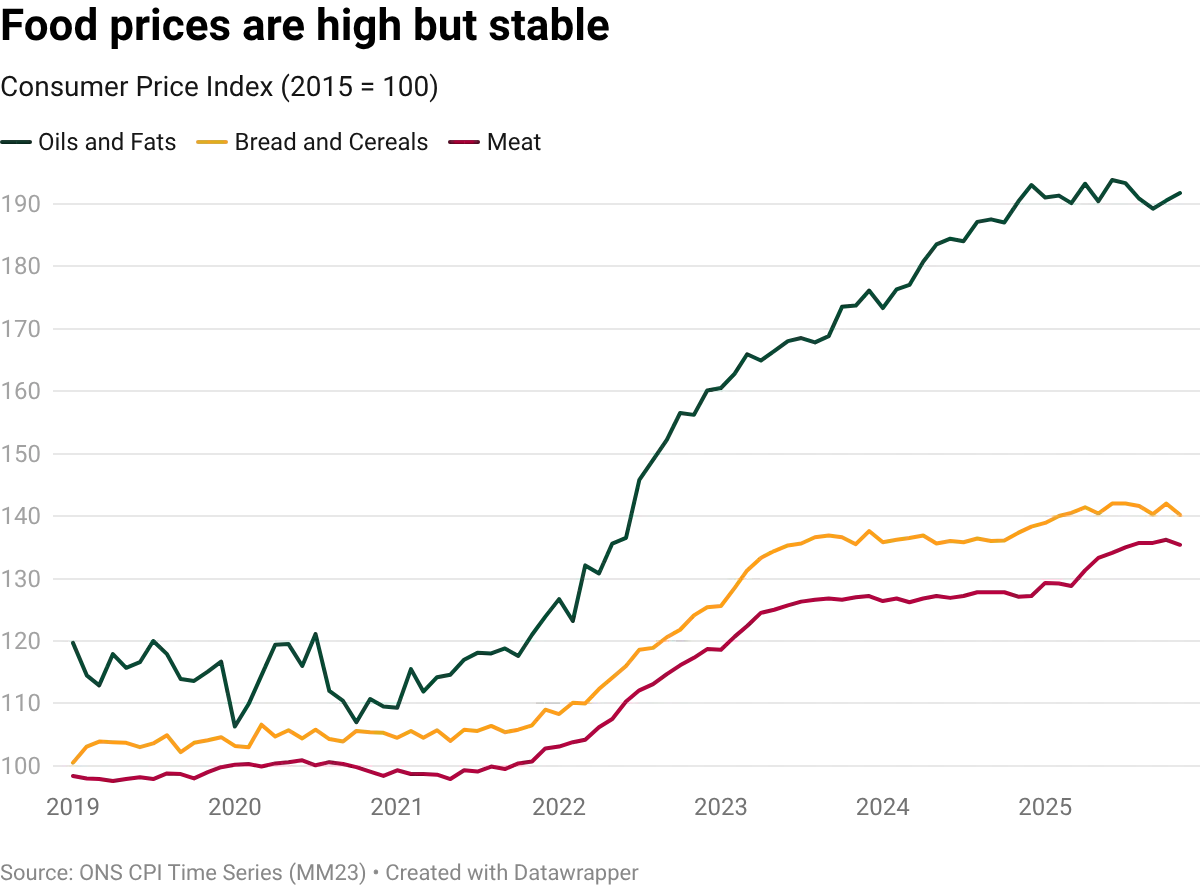

Food prices are high but stable. Food inflation has fallen to around 4.2% (November 2025, year-on-year), compared to 4.9% in October 2025, and highs of 19.1% in 2023. However, because food prices have risen so much over the last 5 years, ahead of increases in wages, many households continue to struggle to afford food, and will continue to experience prices as too high.

Supermarkets have thin margins. The British retail market is competitive, with staple food items priced at little above cost (and sometimes below). Most supermarkets are profitable, but their margins are low, typically in the 2-4% range. If the Government wants to tackle food prices, it must find ways to reduce input costs faced by all supermarkets across the board.

However, these input costs are hard to tackle. Aside from higher food wholesale prices, supermarkets face higher energy and labour costs. The Government’s options here are limited. Energy is already effectively subsidised via VAT reductions and government support to renewables, and more fundamental reforms (such as electricity market reform and reducing dependence on gas) take time. Reducing wages (e.g. through the national minimum wage) would be counterproductive for living standards. Similarly, changing the 0.5% payroll levy for apprenticeships is likely to be politically difficult, and undesirable in a sector that makes heavy use of apprentices..

When it comes to fiscal policy, the Government also has limited options. Supermarkets are unlikely to become cheaper in the short term without cuts to taxes and levies on those businesses, and recent business rate increases push in the opposite direction. Other than reducing VAT, which is undesirable because it is a relatively more efficient tax, the scope for short-term fiscal action is minimal.

However, there are two promising routes to reduce food prices, which we outline.

Proposal 1: Closer EU alignment

The Government should aim to quickly secure sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) and veterinary agreements with the EU. These would reduce importer costs and increase trade volumes, by removing export health certificates (EHCs), documentation checks, and risk‑based physical inspections. Many of these savings could be passed onto consumers. Estimates suggest that both deals together could reduce EU food import prices by 3-6% by 2030, depending on the depth of EU alignment.

A further step would be a bespoke customs arrangement that would avoid the need for rules of origin checks. Depending on the arrangement, this could impact on the UK’s ability to set its own tariffs.

The UK could also abolish or zero‑rate the Common User Charge (CUC) for EU SPS consignments entering via Dover, and cap any local port‑health charges for EU goods at a token level through 2029. This can amount to ~0.5% of a consignment’s value, potentially passed on to consumers. Ultimately this would have to be paid for by the Exchequer.

Similarly, the UK could unpause and deliver the Single Trade Window, so that importers can file once across agencies. This reduces fees, duplications and delay, though the impact is likely to be small, and the cost would be borne by the taxpayer.

Proposal 2: Planning reform

Current planning constraints limit the availability of lower-cost shops to consumers. Incumbent supermarkets can use the National Policy Planning Framework (NPPF) to prevent new entrants, typically low-cost disrupters like Lidl or Aldi, from increasing competition in that area.

The previous Labour Government took action against supermarket anti-competition practices by banning exclusivity agreements with landlords and restrictive covenants placed on land. However, the NPPF preference for town centre retail is not well-suited for low-cost food retail and is relied upon by incumbents. Often incumbents request a judicial review of the local authority planning decisions with the purpose of delaying the new entrant and increasing their costs of entry.

To rectify this, the Government could introduce a permitted development right (PDR) or strong national policy support for new supermarkets. The aim would be to increase and speed up the number of approvals for new supermarkets, increasing competition, particularly where there are new low-cost supermarkets in areas where competition is limited. In these areas, the impact on food prices experienced by households could be significant because of a new cheaper option locally, and national downward pressure on competitor prices (e.g. ‘Aldi price matching’). Greater competition also helps equalise access to the lowest-cost food, reducing the advantage enjoyed by customers who can travel further and buy in bulk.

The Government should also consider allowing developers to use a portion of already agreed section 106 contributions where they cannot find an housing association to take the affordable homes to instead provide on-site lower rent supermarkets.

Other options

Below are some further options that could be worth exploring, though some come with political and economic trade-offs.

- Reduce electricity costs for retailers and producers. Removing carbon price support would lower electricity bills and could support the climate transition, as its net effect is to make electricity more expensive relative to gas. This levy was designed to discourage coal-based electricity production, which is no longer a part of the UK grid. Instead, the levy pushes up electricity prices for households, discouraging switching from gas and petrol to electricity (for heating and transport needs respectively) A broader package (e.g. removing other carbon levies) could reduce prices further. Cold storage, meat processing, dairies and bakeries have particularly high energy costs

- Empower local authorities to set their own Sunday trading laws, making it easier for households to shop at larger, cheaper supermarkets on Sundays, reducing weekly bills. Corner shops (including those owned by national chains) cost consumers 10-20% more than large supermarkets, both through direct price differences and restricting access to multi-buy offers. Worker rights are protected as retail workers maintain their legal right to opt out of Sunday working (Employment Rights Act 1996).

- Lock in and de‑risk seasonal farm labour, e.g. by guaranteeing a multi-year seasonal worker scheme allocation through to 2029. This is particularly important for products mostly sourced from UK farms, such as fresh vegetables (e.g., >95% of carrots are sourced within the UK).

- Groceries version of the Fuel Finder service. A government-operated database where supermarkets can upload the price of a small basket of reference goods (e.g., pint of milk) could help stimulate further competition in the retail sector, and help households access cheaper alternatives.

The authors acknowledge research support by Systemiq with the preparation of this note.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]