Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. The case against stamp duty

- 3. Alternatives to stamp duty

- 4. Our proposal: A proportional property tax

- 5. Additional measures

- 6. Authors

- 7. Appendices

Summary

Britain’s Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) is a tax on aspiration. It bungs up the property market and makes it costly to move house. As a result, people stay in the wrong place for longer: workers pay a penalty for moving to new job opportunities, empty-nesters are effectively fined for downsizing, and new parents can’t afford homes large enough for their families.

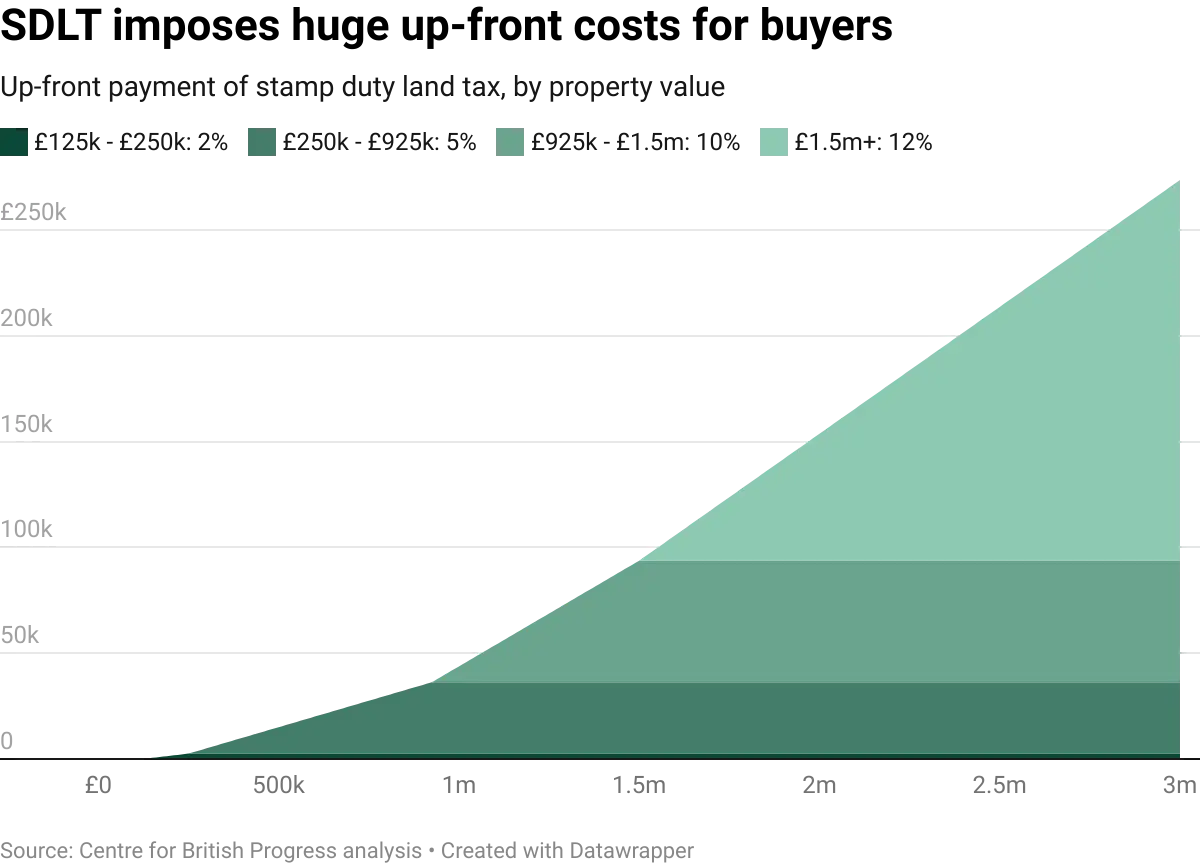

Stamp duty is costly and unfair. For buyers, it creates a double punishment: when house prices increase, so does the tax bill. On average, SDLT costs a buyer £4,547, which could otherwise go towards a deposit, reducing interest on mortgages, or allow buyers to afford a better house. If life demands several moves in a short number of years, stamp duty is merciless. In short, SDLT exacerbates the housing crisis: adding friction to a market that is already failing British households.

As the Chancellor looks to review taxes and raise revenue, SDLT is surely near the top of the list for reform. But anyone calling for the abolition of stamp duty must find a way for the Treasury to plug the resulting £11 billion fiscal hole.

The economist’s solution is to replace SDLT with an annual property tax. This removes the distortions and unfairness created by stamp duty, creating instead a more consistent tax revenue stream. However, an annual property tax comes with new problems. Applying such a tax to all current homeowners would be unfair, as many have already paid hefty SDLT bills on their homes. But applying it only to new purchases means that the Exchequer immediately loses revenue from SDLT.

The challenge is therefore to find a scheme which is simultaneously:

- Efficient: the new scheme must offer an alternative to SDLT and its inefficiencies, such that there is no tax on property transactions.

- Fair: the scheme should not apply to existing owners, who have already paid SDLT.

- Revenue-positive: given the current fiscal climate, it must raise money for the Exchequer from day one.

This report sets out a scheme which meets these requirements. Our base proposal involves phasing out SDLT and replacing it with an annual progressive property tax (PPT). The PPT would:

- Only apply from the next sale of a property. No current owner will be affected until they buy their next house.

- Provide choice. Anyone buying a home in the next ten years can choose between either paying SDLT or committing to an annual PPT. Crucially, this means that no-one is worse off from this aspect.

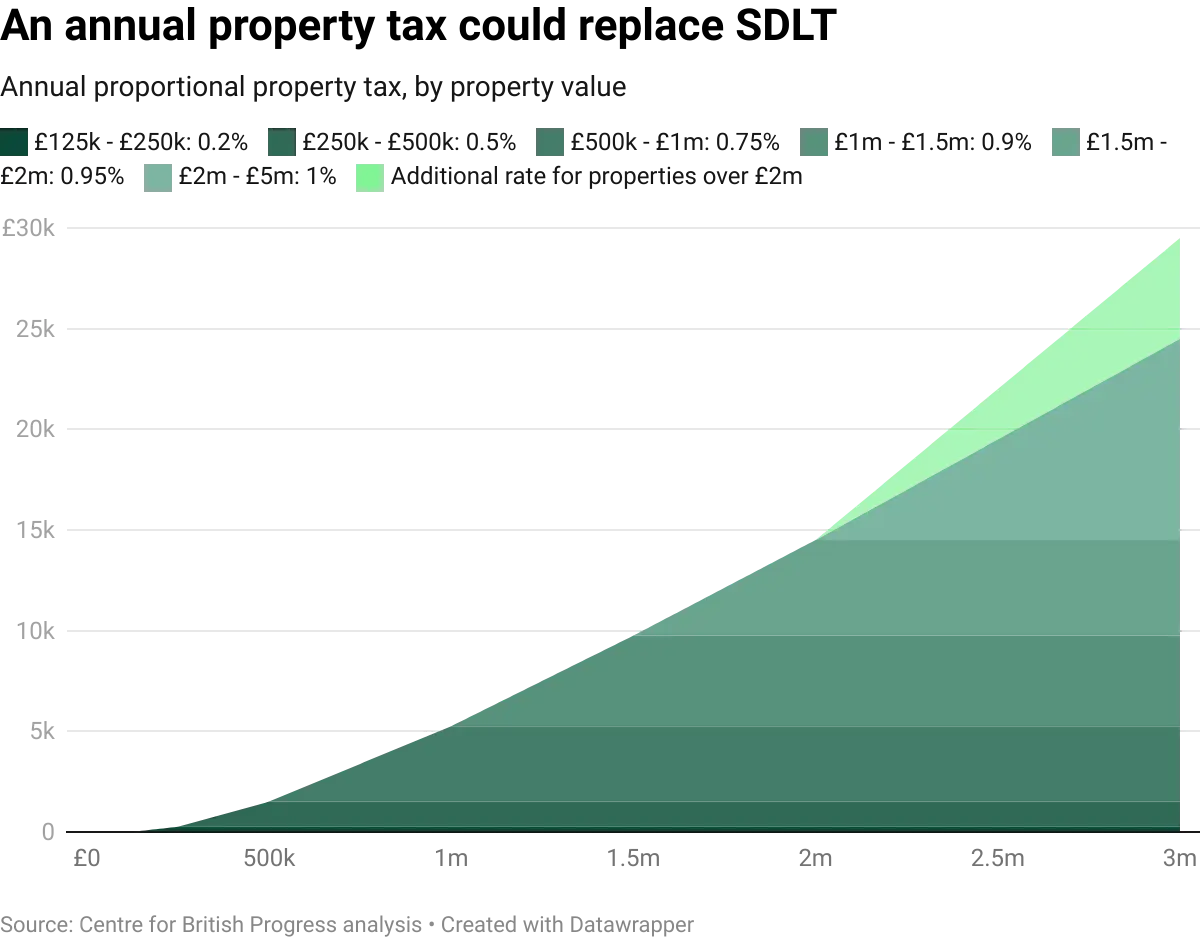

- Apply at 0.2% per annum for properties sold for between £125k and £250k, rising progressively up to 1.1% for properties sold for over £5m.

- Completely replace SDLT: once a property has ‘transitioned’ away from SDLT (which can only happen at a sale), it is permanently subject to PPT.

To ensure that a new progressive property tax (PPT) is revenue-positive from day one of implementation, we propose the following additional measures:

- A ten-year ‘transition phase’, so that HMT does not immediately lose SDLT revenue. In the first year of implementation, buyers can opt for a 10% discount on their stamp duty bill, and instead commit to paying 10% of our proposed annual property tax. In year 2, they can choose to pay a 20% SDLT discount and 20% of the annual PPT, and so on.

- An annual additional rate of 0.5% levied on the value above £2m for high-value properties. (So a home worth £2.1 million would pay an additional rate of 0.5% x £100,000 = £500 a year.) This would apply immediately, but allow deferral with interest for illiquid homeowners.

- Replacing the ATED bands on enveloped property by harmonising them with our proposed PPT rates and reducing the threshold on eligible properties to £125,000.

Our modelling suggests that an optional proportional property tax, phased in over 10 years, would eventually generate far more revenue for the Exchequer when compared to SDLT. With the introduction of the additional measures described above, it can also generate positive revenue from day one, compared to the SDLT baseline.

Together, these measures would:

- Raise around £1.7bn above the current SDLT baseline in year one of implementation, rising to around £8bn annually above baseline by 2050.

- Reduce long-term borrowing costs due to forecast future revenue.

- Create more stable and predictable revenue for HMT.

- Increase productivity, GDP and tax revenue resulting from new economic activity. This includes new property transactions (which otherwise would have been made impossible due to the SDLT wedge), and dynamic effects resulting from workers moving to higher-paying jobs.

- Have no effect on the vast majority of homeowners – there are between 140k and 170k properties worth more than £2 million in England and Wales, representing between 0.55% and 0.65% of the housing stock.

- Create substantial savings for buyers, who no longer have to pay SDLT (or a reduced proportion, during the transition) on their purchases.

Below we outline how this tax would be applied to different properties:

Property Band | Current marginal SDLT rate | Our proposed marginal property tax (annual) |

|---|---|---|

£125,000 or less | 0% | 0% |

£125,001 to £250,000 | 2% | 0.2% |

£250,001 to £500,000 | 5% | 0.5% |

£500,001 to £1,000,000 | 5% (up to £925k), then 10% | 0.75% |

£1,000,001 to £1,500,000 | 10% | 0.9% |

£1,500,001 to £2,000,000 | 12% | 0.95% |

£2,000,001 to £5,000,000 | 12% | 1% |

More than £5,000,001 | 12% | 1.1% |

Specific examples:

Sale price | One-off stamp duty bill (current system) | Annual property tax bill (our proposal) |

|---|---|---|

£100,000 | £0 | £0 |

£250,000 | £2,500 | £250 |

£500,000 | £15,000 | £1,500 |

£1,000,000 | £43,750 | £5,250 |

£5,000,000 | £513,750 | £44,500 |

Our proposal gives buyers choice while replacing SDLT – an unpopular and inefficient tax – with a new, progressive property tax. The vast majority of people will see no change to their tax bill, and everyone will benefit from the removal of high upfront costs to buying a house. Buyers will pay less to buy a house, and sellers will receive more. This system would be fairer, progressive, and create a better deal for the Treasury and the taxpayer. Crucially, it would go some way to unblocking our housing market, ensuring that people can easily and affordably move to the housing they need.

Finally, while the immediate and primary goal of this proposal is to replace a deeply flawed tax, it also establishes a framework that could be expanded in the future. A successful transition to a national property tax could pave the way for a widely-desired reform of local government finance, including the outdated council tax system. Our proposal focuses entirely on the most urgent priority: removing a major barrier in the housing market with a fair, progressive, and revenue-secure alternative. However, by unlocking considerable revenue over the long-term, the additional fiscal headroom created would allow future governments to subsume all property taxation under this broad scheme and ensure greater equity in capturing revenue from wealth accumulation while minimising economic distortions.

The case against stamp duty

The list of economic sins committed by stamp duty is almost as long as the list of economists who have called for its abolition. In our recent survey of economists and other policy experts, respondents identified stamp duties as the most damaging of all the taxes under consideration, and proposed a considerable decrease.

SDLT is economically inefficient, structurally inequitable, and badly targeted for revenue generation.

1. Economic inefficiency

Since the main purpose of taxes is to fund public services and redistribute wealth, taxes are rarely designed with economic efficiency in mind. But some taxes are far more efficient than others. The most efficient are "Pigouvian" taxes, which target harmful economic activity (such as pollution) to encourage more socially beneficial activities, and raise money in the process.

Other taxes are less efficient, but nonetheless worthwhile, such as taxes on ‘value added’ (like VAT), or many income taxes. These have some “deadweight loss”, as they can lead to people working or consuming less than they would like to, but this inefficiency is limited by how responsive the tax base is: it is difficult for people to stop earning income or consuming goods, so the tax is less distortive.

The worst taxes are those that punish economically beneficial activities, especially when these activities can easily be avoided. Taxes on property transactions are in this category, and this problem is magnified by the punitive top rates of SDLT: they add friction to an important market and can be entirely avoided by simply not transacting.

The primary economic damage caused by property transaction taxes is that they prevent people from living in the housing that best suits their needs and life stage. New parents may need an extra bedroom, while empty-nesters may want to downsize. Jobs, marriages, and family commitments might require moving to new locations. Stamp duty adds significant friction to each of these moves and, at the margin, can be the critical factor that makes a necessary move impossible or significantly delays it.

This "lock-in" effect imposes a substantial cost on both individuals and society. Workers unable to move for a better job might be forced to accept lower wages, which is not only worse for them but also results in less overall economic output and lower tax receipts. The damage can be lasting: a young person who cannot afford to move for a desirable job may miss out on critical work experience, with negative consequences for their career progression and lifetime earnings.

Empirical research confirms this: UK data suggests that a mere 1% stamp duty reduces housing market transactions by approximately 10%. This is also supported by data from Scotland, while evidence from Toronto, Canada reveals that stamp duties lead to higher rent-to-price ratios and reduce home ownership relative to buy-to-let.

2. Structural unfairness

Stamp duty disproportionately hits those in more difficult situations, particularly those forced by life’s circumstances to move house. These people end up bearing a much greater tax burden over their lifetime than those fortunate enough to not have to move as often. This means that two households with identical incomes and wealth can face vastly different lifetime tax bills purely because of how frequently they need to move house – something which might be outside their control.

Second, stamp duty disproportionately penalises those who struggle to pay for a deposit, eating into a larger share of their savings towards their new house. This disproportionately disadvantages those from less privileged backgrounds.

Third, the tax has unequal geographic impacts, effectively imposing higher rates on those living in places where housing costs are higher. Low income households in London may pay more tax over their lifetime than high income families in other parts of the country, due to SDLT’s disproportionate effects.

Lastly, SDLT does little to tackle true wealth inequality. It is blind to housing wealth accumulated without transaction: a junior doctor, forced to relocate multiple times for their career, can pay far more in tax over a decade than a wealthy City lawyer who remains in the same family home. This also creates perverse incentives, encouraging wealthy owners to avoid moves that would free up housing space and generate economic value.

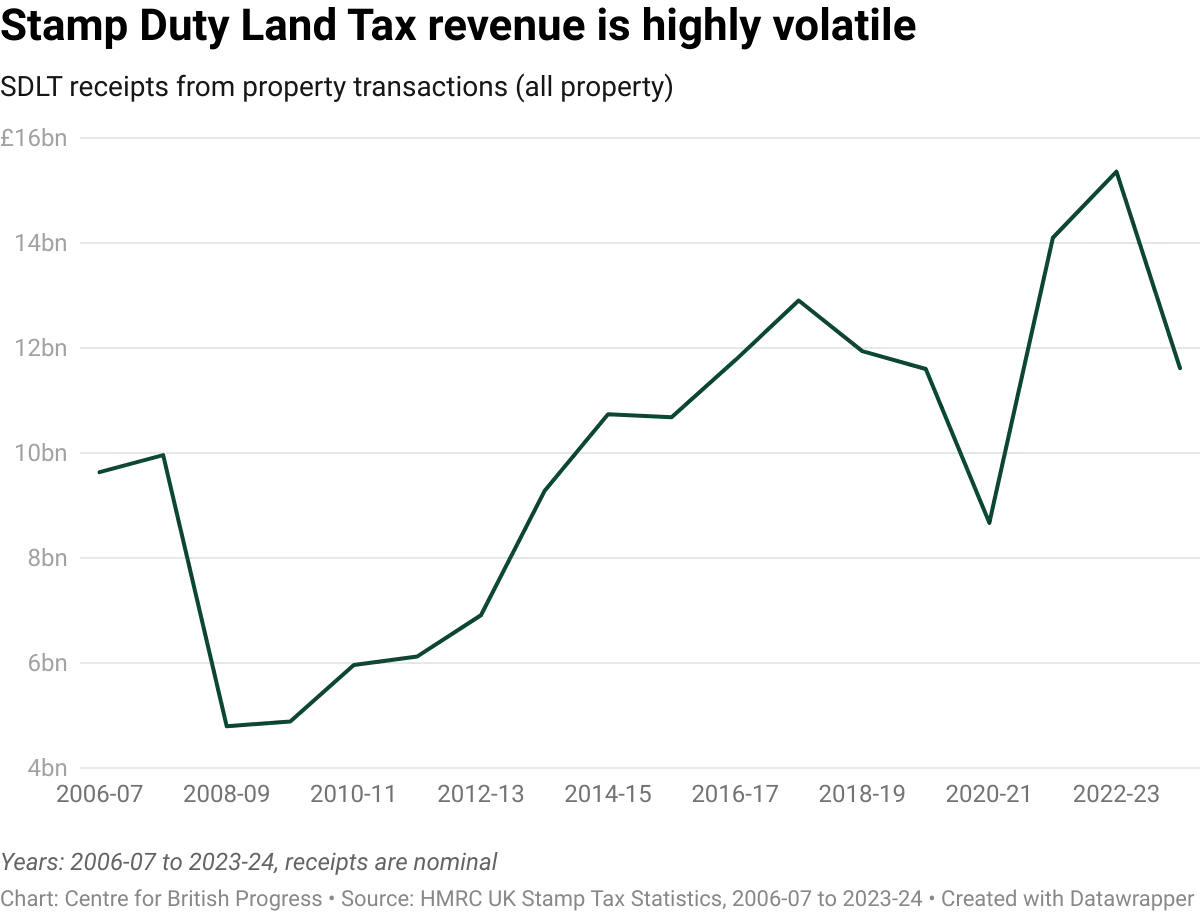

3. Volatility

Since SDLT is hitched to property purchases, Treasury revenue from SDLT tracks volatile cycles in the housing market. HMRC data shows that, over the full series of 2003-2024, annual receipts are roughly one-third above or below their long-run average. This is more than twice the variability observed in the main broad-based taxes, such as VAT and income tax. During the global financial crisis, receipts almost doubled from about £5 billion in 2003-04 to just under £10 billion in 2007-08, then collapsed to £4.8 billion in 2008-09. The pandemic produced another sharp swing, with receipts falling to £8.7 billion in 2020-21 before jumping to £14.1 billion in 2021-22. This variability means the Treasury misses out on a stable stream of funding that is required by an efficient tax system.

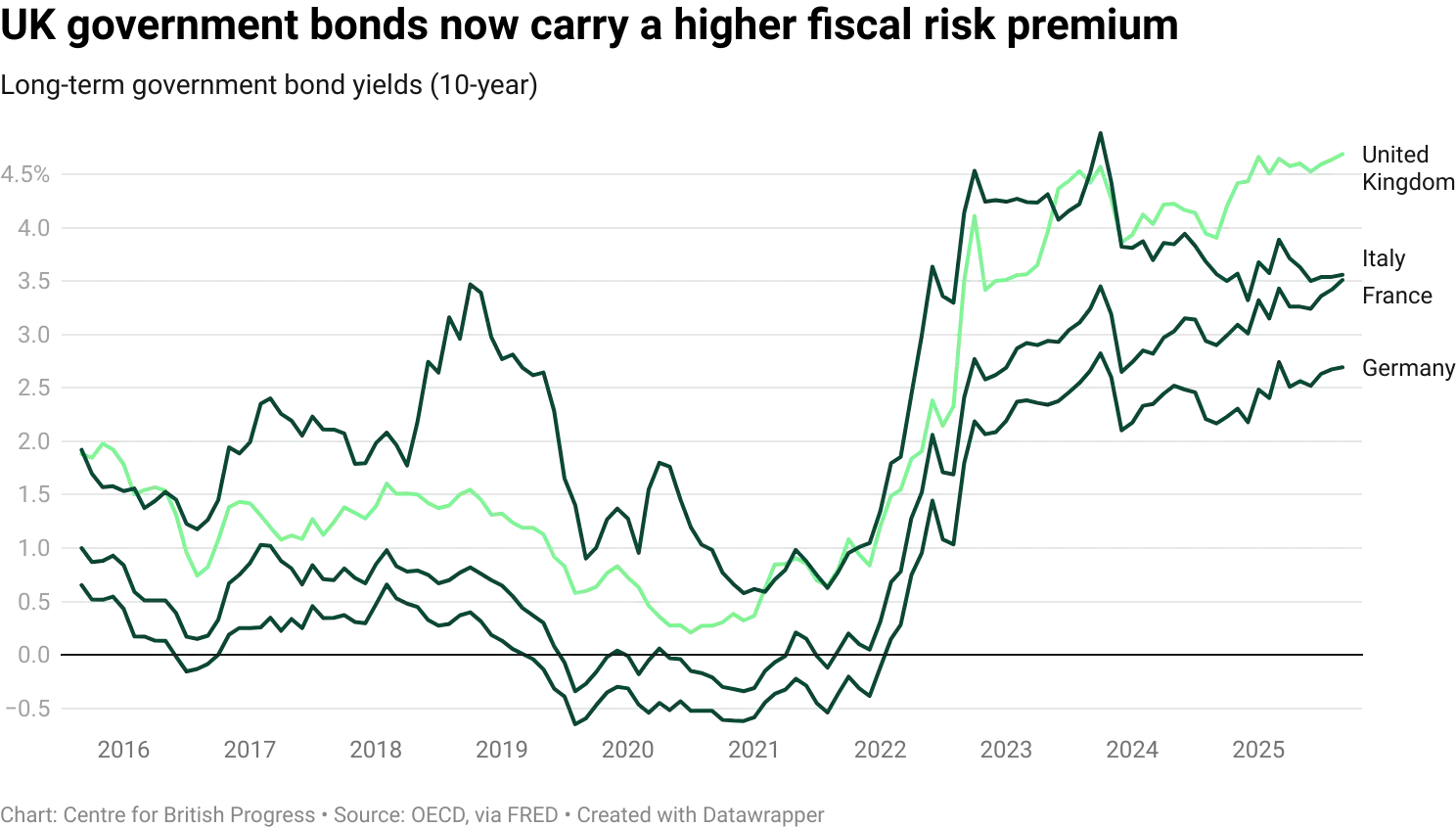

While the procyclical nature of property transactions allows SDLT to act as an automatic stabiliser for the economy, this comes at the cost of making it a highly volatile and unpredictable source of government revenue. During periods of reduced economic activity, house purchases decline along with most economic activity, which means the Treasury loses revenue precisely when counter-cyclical support is most needed. All other things being equal, more cyclical revenues will likely mean that gilt investors demand higher gilt yields to compensate for increased risk.

Everyone agrees it should go

The Institute for Fiscal Studies' comprehensive and respected Mirrlees Review concludes that there is "no sound case" for retaining SDLT in its current form, characterising it as a "textbook case of a bad tax". The Review suggests that SDLT is one of the most distortionary taxes in the UK tax system, and that its removal would result in a meaningful improvement to social welfare. This conclusion is echoed by a recent report, Tax Reforms for Growth, co-authored by experts from academia and think tanks across the political spectrum, which makes abolishing Stamp Duty one of its primary recommendations for property tax reform. The case for its replacement is overwhelming.

Modelling the economic cost of SDLT

We use a simple model of the housing market to assess alternatives to SDLT. Unlike traditional economic models under perfect competition, search models capture how buyers engage in a costly and time-consuming process of negotiating a sale price with sellers, who also pay a cost to list their properties. Incorporating this allows us to treat the volume of transactions as unfixed, and therefore make better assessments about the efficiency impact of different taxes.

Using a search and matching model, we set rates for alternative taxes so that they raise the same total revenue over the long term as SDLT does now. We simulate and assess three different regimes against the current SDLT baseline:

- Upfront SDLT (baseline): This is the current system. Its defining feature is a large tax paid by the buyer at the point of purchasing a new property. Its primary economic effect is to increase the cost of buying a property, proportional to its value. Buyers face an immediate liquidity shock. SDLT acts as a direct penalty on moving house, discouraging people from relocating.

- Deferred SDLT: A variation on the current stamp duty model which alleviates the immediate burden on buyers by allowing them to defer their tax liability beyond the point of purchase. This could be paid gradually over time or deferred entirely until the property is sold, and outstanding tax could accrue interest. This would remove SDLT’s harmful impact on liquidity when buying a house, and mitigate some of the unfairness in the current system. But economic distortions related to reduced mobility and deadweight loss would persist, since transactions are still financially penalised. Our modelling assumes that the tax is maximally deferred to the point of the next sale.

- Annual Proportional Property Tax (PPT): Instead of a large, one-off levy at the point of purchase, homeowners pay a smaller, regular annual charge. This is calculated as a fixed percentage of the property's purchase price. This removes inefficiencies by making the tax a predictable ongoing cost of ownership rather than a costly upfront barrier. It completely decouples taxation from the decision to move, since the tax would be paid every year regardless of whether one moves house. In our model, this is implemented as a direct payment from households to the Treasury, as an unavoidable, ongoing cost of ownership. This directly addresses SDLT’s core economic distortions, removing friction from the housing market.

- No Tax: This final scenario serves as a theoretical benchmark. It represents an ideal, frictionless world operating at maximum efficiency. It is not a realistic policy goal because it requires taxes to be imposed without cost in some other way, but it provides a yardstick against which we can measure the economic cost - the "deadweight loss" - imposed by other tax systems.

Results

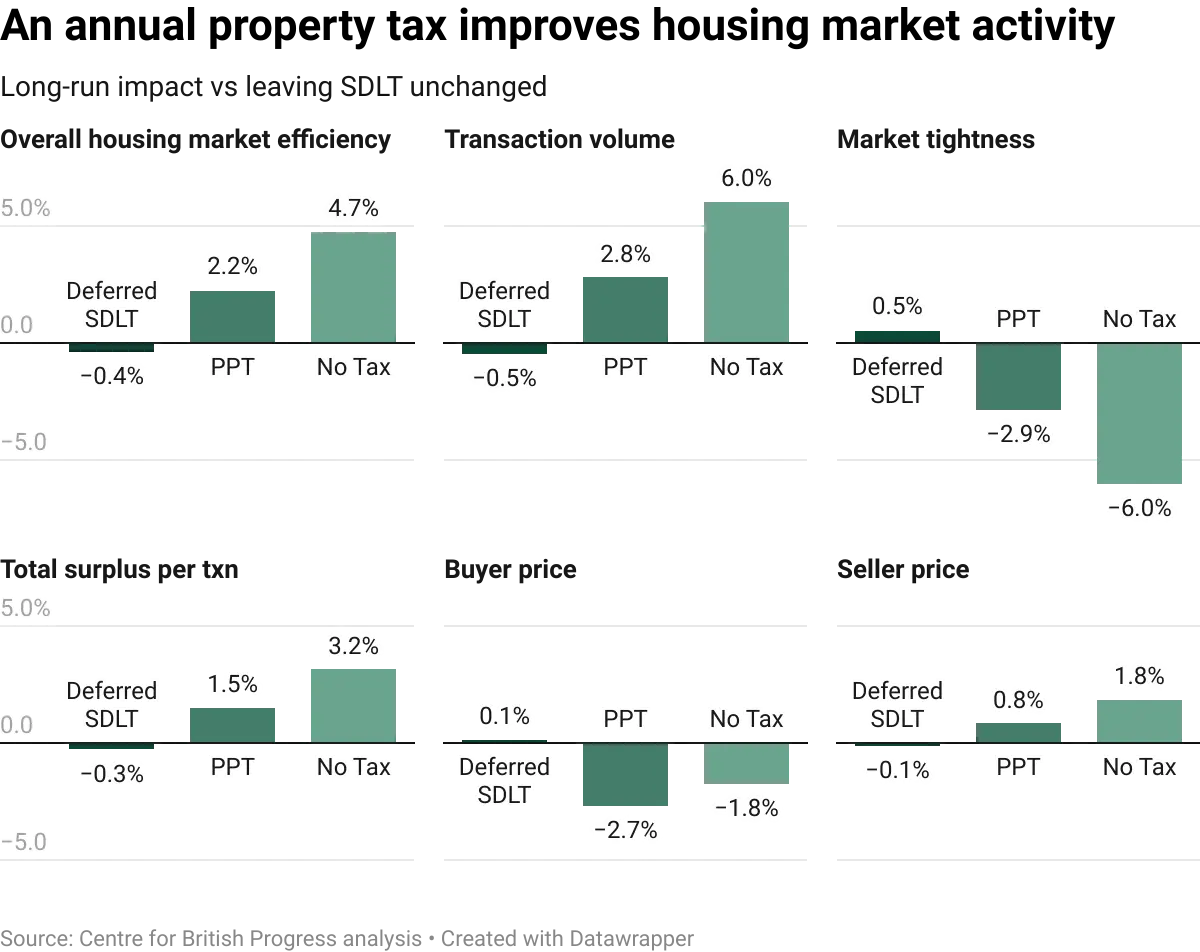

The graphs below show the long-run impact of each reform relative to the SDLT baseline.

Market Dynamics

The deferred SDLT option leads to a 0.5% reduction in transaction volume, compared to standard SDLT. This is because it reduces the value of selling a property for current owners, who face a tax bill at point of sale. We do not model borrowing constraints, but it is plausible that the combined effect would make a deferred tax less distortionary. Without a liquidity effect, the “lock-in” effect of deferring tax liability is even worse than under the current system.

However, replacing SDLT with a Proportional Property Tax (PPT) has a noticeably positive impact on market dynamism, increasing transaction volumes by 2.8% per quarter. The most direct mechanism here is greater household mobility: the same houses can be exchanged more frequently, as transaction costs have been removed. This facilitates more efficient "right-sizing", where growing families can move to larger homes, older households can downsize, and workers can move for new jobs. We do not model the downstream effects of this, such as the productivity benefits of workers being able to move to new jobs, which would have a further positive benefit.

PPT leads to an increase in vacant properties for sale at any given time. This gives buyers more choice, increasing their chances of finding a suitable property, and gives sellers more confidence to list their properties, creating a positive feedback loop that reduces search costs for everyone. This healthier dynamic is captured by a 2.9% reduction in market “tightness” (defined as the ratio of buyers to sellers).

Prices

By taxing purchases, SDLT lowers prices by reducing what buyers can afford to pay (since they have to put money towards paying SDLT), which in turn reduces profitability for developers and discourages new construction. Conversely, a PPT should incentivise new construction, which would help mitigate price rises, but this effect is likely to be very limited in practice given the restrictiveness of Britain’s planning regime.

A larger impact on prices comes from PPT’s removal of the SDLT "tax wedge", the gap between the price a buyer is willing to pay and amount the seller receives. This wedge acts as a barrier to agreeing a price, preventing many mutually beneficial transactions from taking place. PPT eliminates this wedge by fundamentally changing how the cost of tax is reflected in a property's price. Because the annual tax is a predictable, ongoing cost of ownership, a rational buyer accounts for this future liability by lowering their upfront offer. This affects house prices in two ways. First, the after-tax price paid by buyers falls by 2.7%, largely as a result of removing the tax mark-up, making the headline price of a home lower. Second, since SDLT is removed and buyers have more money to spend on a new home, the price received by sellers increases by 0.8%, allowing them to retain more of their home's equity.

The simultaneous benefit to both buyer and seller illustrates the positive sum nature of removing SDLT: there is more value available for everyone. This is because of the removal of lost time and money spent searching, the financial cost of delaying a move to save for the tax, and/or lost professional opportunities from turning down jobs in other locations. We can further quantify this increase in available value by tracking the amount of surplus per transaction, which rises by 1.5%. This newly unlocked surplus is what allows for a better outcome for both buyer and seller.

Welfare implications

The economic value destroyed by an inefficient tax is known as "deadweight loss". For SDLT, this is the sum of all the desirable moves that are prevented by the tax. Our simulation implies that a shift from SDLT to a long-term revenue neutral PPT increases welfare by 2.2%. This captures the economic value of a more dynamic housing stock that is also larger in the long run, and the removal of the price wedge that prevents mutually beneficial deals. This gain contrasts with the outcome under a deferred SDLT, where welfare slightly decreases. Unlike the deferred SDLT proposal, a proportional property tax shifts the incidence to a less distortionary base.

Alternatives to stamp duty

The most obvious alternative to SDLT is replacing it with an annual tax. This can be levied either on the value of the property, or on the value of the land alone (excluding the value of any structures on the land).

A pure land tax is unlikely to be theoretically optimal, as there is no strong economic reason to exclude the value of buildings and improvements from the tax base. Administratively, it requires a contentious valuation process fraught with the risk of error, which could also provoke political backlash. From a fiscal perspective, taxing land alone carries over the distortion created by exempting property transactions from value added taxes, like VAT. A tax on the full value of a property, in contrast, offers a solution to both challenges: it is administratively simpler and partly addresses this distortion.

The main appeal of a property tax is that it avoids all the problems with SDLT outlined above: a property tax would not lead to the perverse incentive to avoid buying or selling based on transaction cost, which would free up the housing market. It would be fairer for ordinary people, as their tax burden would be linked to the value of their property, rather than being a penalty for moving house. It would provide a stable source of revenue for the Treasury, since receipts would not be attached to property market volatility.

Both land and property taxes have the added benefit of high inelasticity: they are almost impossible to avoid, since one cannot move housing properties out of the country, and every property must be owned by someone.

Several alternatives to SDLT have been proposed, focusing on taxing either land or property:

- Tax Policy Associates have proposed replacing stamp duty, council tax and business rates all in one go with a land value tax.

- Onward think tank has proposed a proportional property tax with a tiered distribution mechanism to allocate revenue between central and local governments.

- The Adam Smith Institute has changed its thinking on the matter; while earlier proposals suggested a tax on rental income and imputed rents achieved by reforming the regressive top end of Council Tax, their recent report leans towards a tax on the underlying land value.

- To manage the fiscal impact, Britain Remade’s Michael Hill proposes an annual charge based on the property value, and seeks to address revenue neutrality by suggesting a pre-payment of this new charge equivalent to the SDLT liabilities being replaced to ensure short-term neutrality.

However, the critical challenge for any reform is fiscal neutrality while avoiding double taxation of recent house buyers. Any proponent of removing SDLT must address the resulting revenue shortfall – estimated around £8.6 billion for residential properties, and 3 billion for non-residential properties in 2023/24, though this can vary significantly between years – and explain how this hole can be filled.

SDLT accounts for just under 1.5% of public sector receipts (as of July 2025). This sounds like a small sum, but the Government is already facing a significant fiscal shortfall, alongside higher borrowing costs and the need to meet Treasury spending rules. The Government has also committed to not raise VAT or income taxes, so any new revenue must come from elsewhere.

The proposals listed above address fiscal-neutrality in quite different ways. The "pre-payment" solution (Michael Hill’s) directly confronts short-term revenue loss by retaining some of the lock-in effect of stamp duty and decreasing revenue in the medium-term, whereas other proposals would create significant revenue shortfalls for years, or in some cases explicitly accept a net fiscal cost, by focusing on long-term viability. None of these proposals raise sufficient funds to surpass the SDLT baseline throughout the duration of a parliament without increasing taxes on a large number of current homeowners.

Our proposal: A proportional property tax

We propose replacing SDLT with an annual, proportional property tax. Our modelling projects an immediate economic dividend from this, due to increased housing market transactions and more houses being on the market.

However, there are better and worse ways of implementing a PPT. For starters, it would be unfair (and politically very difficult) to apply a PPT to existing homeowners who have already paid a hefty SDLT bill, and may have done so recently. Second, we may want to give new buyers the choice between SDLT and a PPT. While we expect that most buyers would prefer a smaller, ongoing charge to a large, upfront hit to liquidity, those who plan to stay in a house for a long time may reason that the upfront payment is cheaper over the lifetime of their ownership. Offering a choice is also a way of ensuring that no one is worse off than in the current system.

The challenge is therefore to find a scheme which is simultaneously:

- Efficient: the new scheme must offer an alternative to SDLT and its inefficiencies, such that there is no tax on property transactions.

- Fair: the scheme should not apply to existing owners, who have already paid SDLT.

- Revenue-positive: given the current fiscal climate, it must raise money for the Exchequer from day one.

We set out a scheme which meets these requirements. Our base proposal involves phasing out SDLT and replacing it with an annual progressive property tax (PPT). The PPT would:

- Only apply from the next sale of a property. No current owner will be affected until they buy their next house.

- Provide choice. Anyone buying a home in the next ten years can choose between either paying SDLT or committing to an annual PPT. Crucially, this means that no-one is worse off from this aspect.

- Apply at 0.2% per annum for properties sold for between £125k and £250k, rising progressively up to 1.1% for properties sold for over £5m.

- Completely replace SDLT: once a property has ‘transitioned’ away from SDLT (which can only happen at a sale), it is permanently subject to PPT.

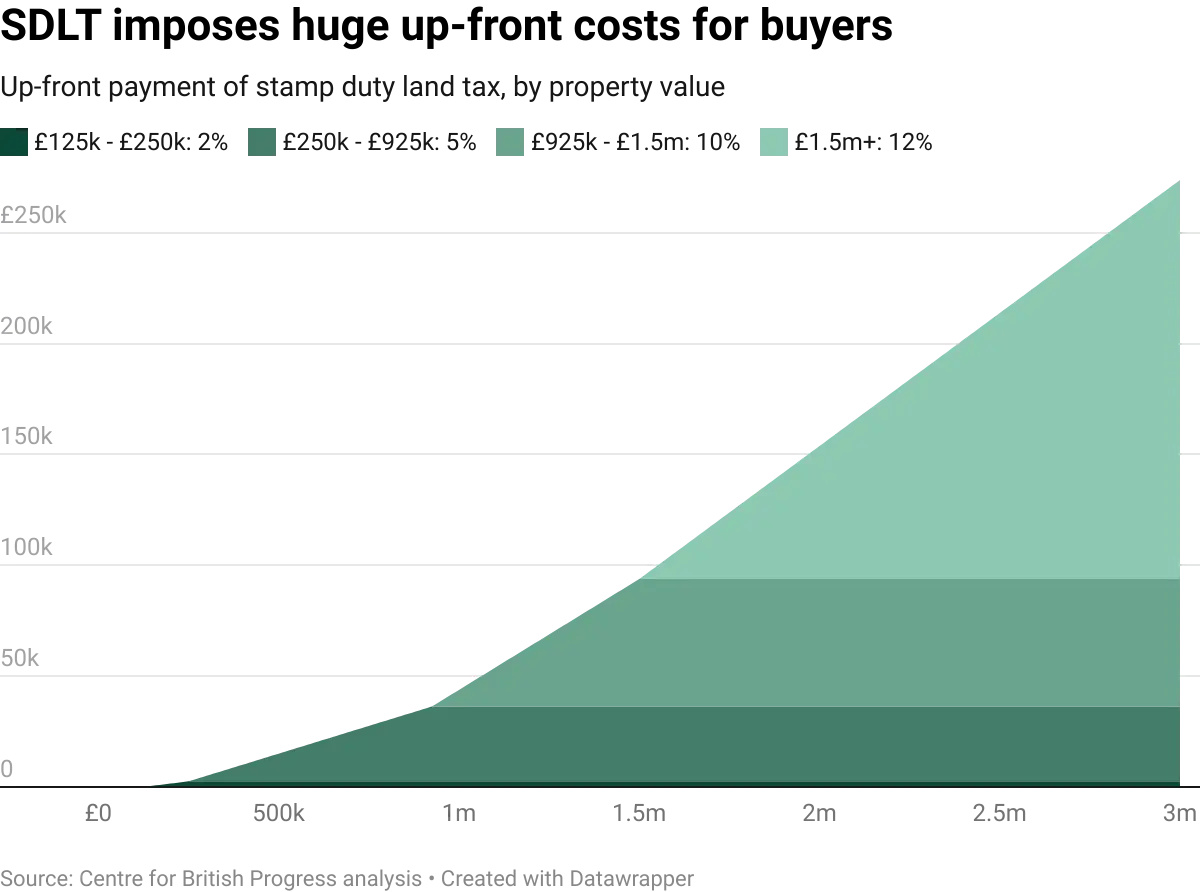

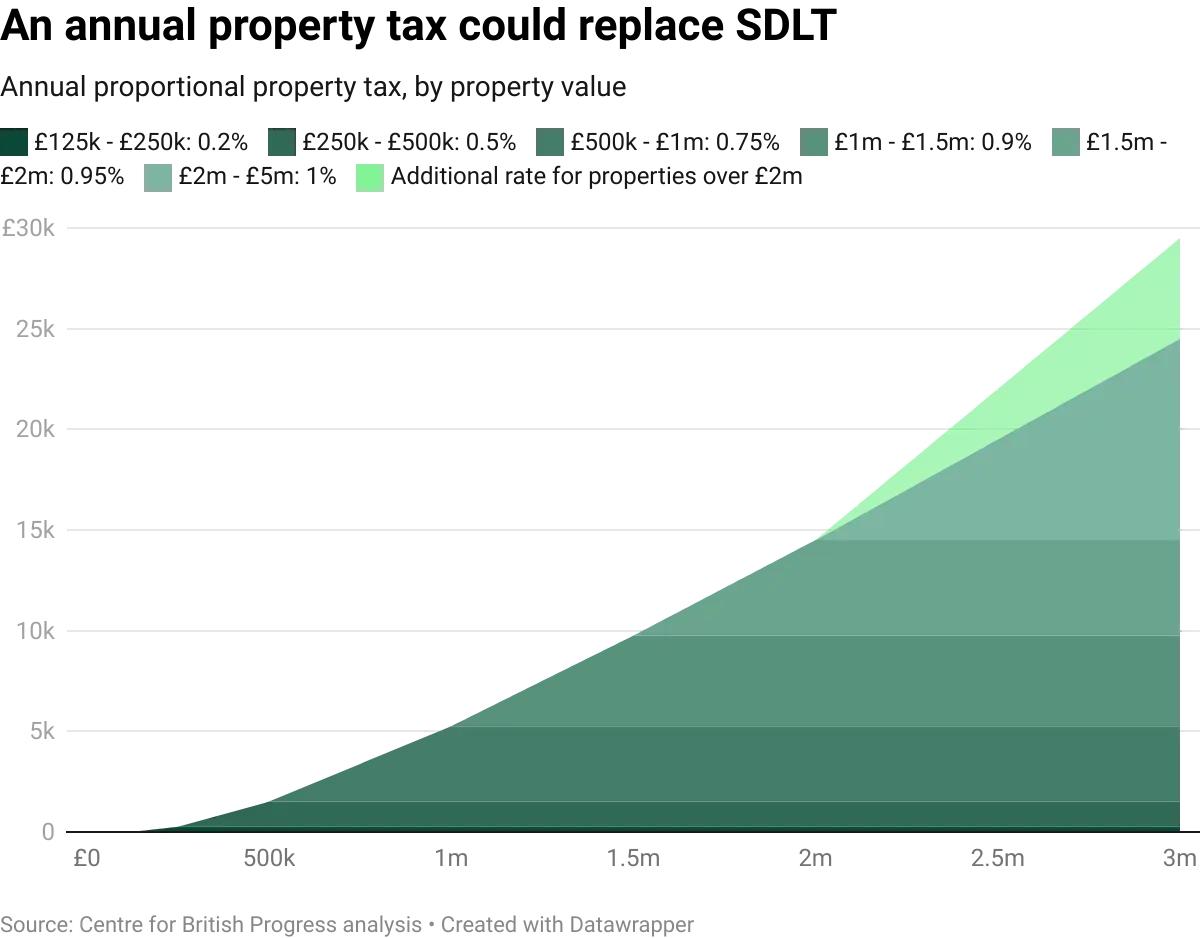

The graphs below illustrate the stamp duty bill faced by buyers of different property values, and how this compares to our proposed annual property tax.

Property Band | Current marginal SDLT rate | Our proposed marginal property tax (annual) |

|---|---|---|

£125,000 or less | 0% | 0% |

£125,001 to £250,000 | 2% | 0.2% |

£250,001 to £500,000 | 5% | 0.5% |

£500,001 to £1,000,000 | 5% (up to £925k), then 10% | 0.75% |

£1,000,001 to £1,500,000 | 10% | 0.9% |

£1,500,001 to £2,000,000 | 12% | 0.95% |

£2,000,001 to £5,000,000 | 12% | 1% |

More than £5,000,001 | 12% | 1.1% |

Specific examples:

Sale price | One-off stamp duty bill (current system) | Annual property tax bill (our proposal) |

|---|---|---|

£100,000 | £0 | £0 |

£250,000 | £2,500 | £250 |

£500,000 | £15,000 | £1,500 |

£1,000,000 | £43,750 | £5,250 |

£5,000,000 | £513,750 | £44,500 |

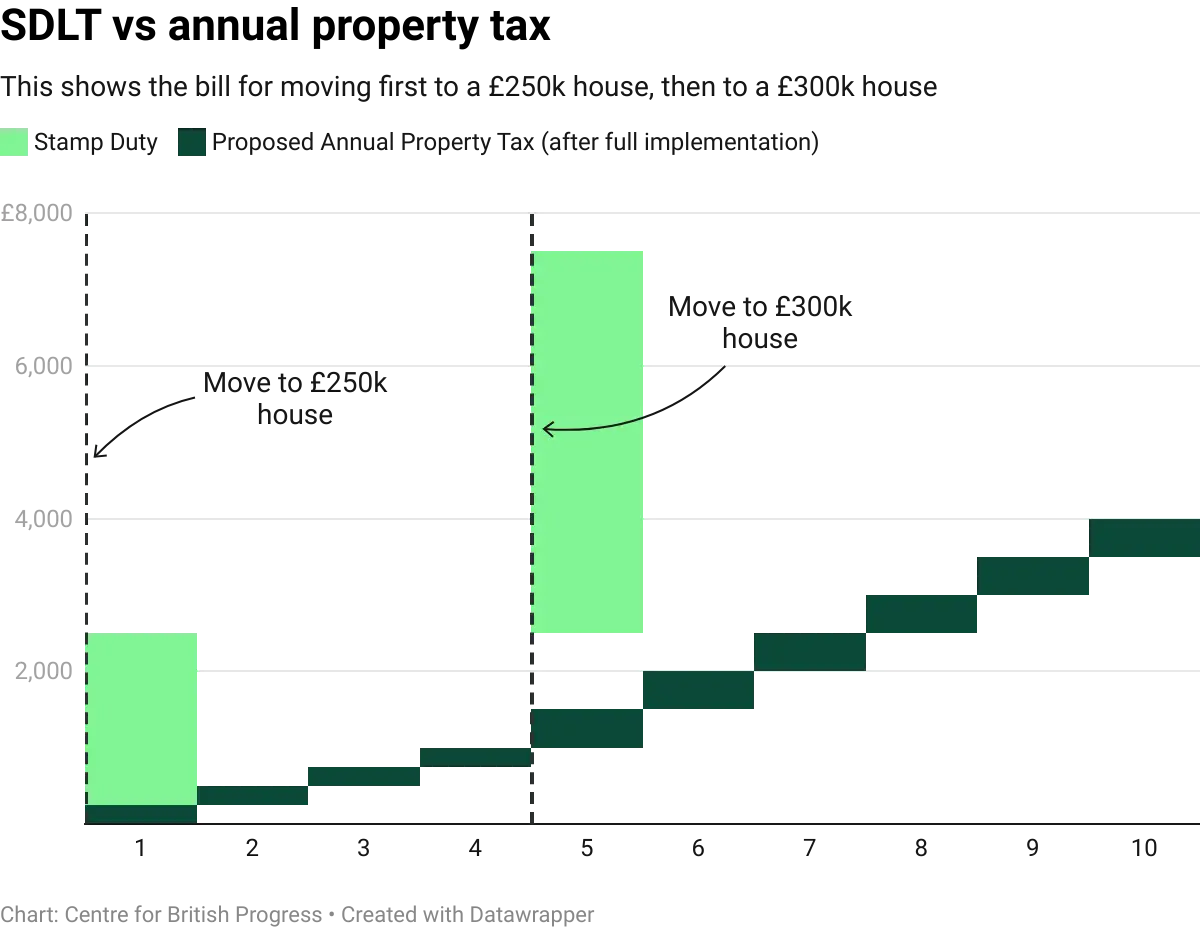

Below we illustrate how our proposal will look for someone buying a property of £250k and then moving to a different property of £300k, once the 10 year transition period is completed.

Economic benefits of replacing SDLT

To model the economic impact of removing SDLT in the UK, we use a study from Australia, which modelled the productivity and tax revenue benefits from removing a stamp duty on housing transactions. Conveniently, Australia’s stamp duty is at a similar rate to the UK’s.

Applying the study’s modelling to the UK, we estimate that replacing the UK’s SDLT with a broad-based annual levy would deliver a permanent 3.38% increase to UK GDP, and retain around 75% of the revenue generated by the stamp duty.

Critically, this gain is driven almost entirely (95%) by a boost to labour productivity as workers moved more freely to suitable jobs. For comparison, an appropriately scaled increase of just over 3% would represent a permanent increase in the size of the UK economy of approximately £91 billion. This strongly suggests that the true economic prize of reform lies not just in the housing market, but in unlocking productive potential through the labour market.

The main difficulty in implementing an ideal tax reform is the immediate and severe impact on tax revenue, which produces an immediate static shortfall. It is important to note, however, that any dynamic output effect from the reform could be more than sufficient to offset this loss entirely; based on the OBR’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook’s estimate for the tax-to-GDP ratio of 37.1 per cent, every £1 billion of static revenue foregone could be fully offset by a permanent GDP increase of just £2.7 billion (0.11%). The OBR is somewhat sceptical of a large GDP impact of eliminating stamp duty, which in turn suggests limited scope for its scoring a large dynamic effect under any proposed reform.

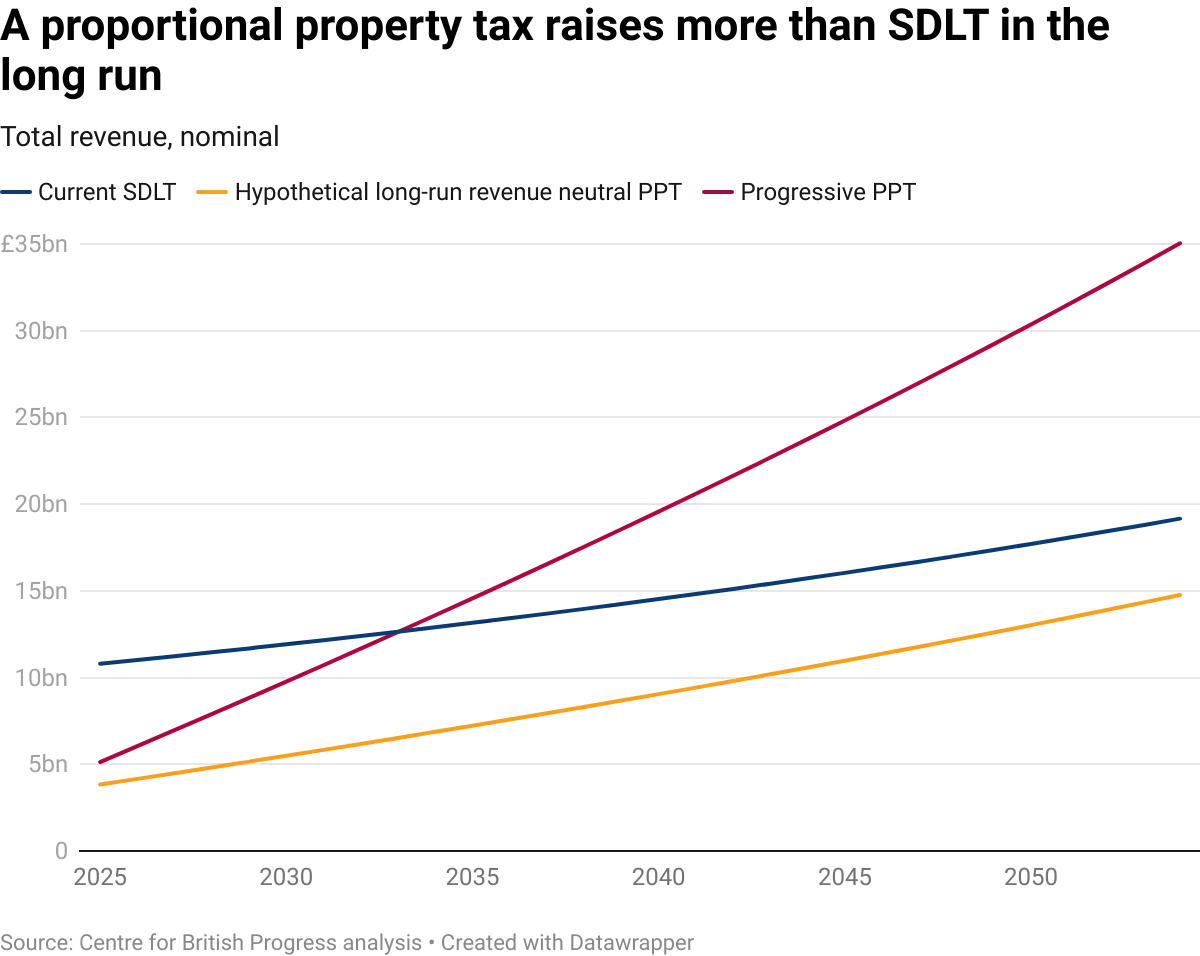

This means that even a powerful dynamic effect would not be captured in direct fiscal accounting. The static revenue gap is so persistent that a fair, gradual transition is not fiscally neutral in the short or even medium term - a problem that remains even if the new tax rates are set considerably higher than the revenue-neutral level, as the graph below illustrates:

The graph shows revenue from the current SDLT regime (increasing in line with inflation), and considers two alternatives. A hypothesised ‘revenue-neutral’ PPT aims to raise the same amount of revenue from different bands of property value, in the long run. Eventually, this raises as much as SDLT, but it takes a very long time to get there – and has an initial revenue shortfall of close to 70% relative to the current regime. This is because even with higher transaction rates, the Treasury receives delayed and spread-out revenue after each sale. Since we only apply the tax to new purchases, it takes a long time for revenue to be recouped.

A more ‘progressive’ PPT schedule of rates, which raises more from higher value properties, eventually generates far more revenue than SDLT would do in the long-run. However, there is still an initial 53% shortfall from the removal of SDLT that would take about 8 years to close.

Solving for revenue in year one

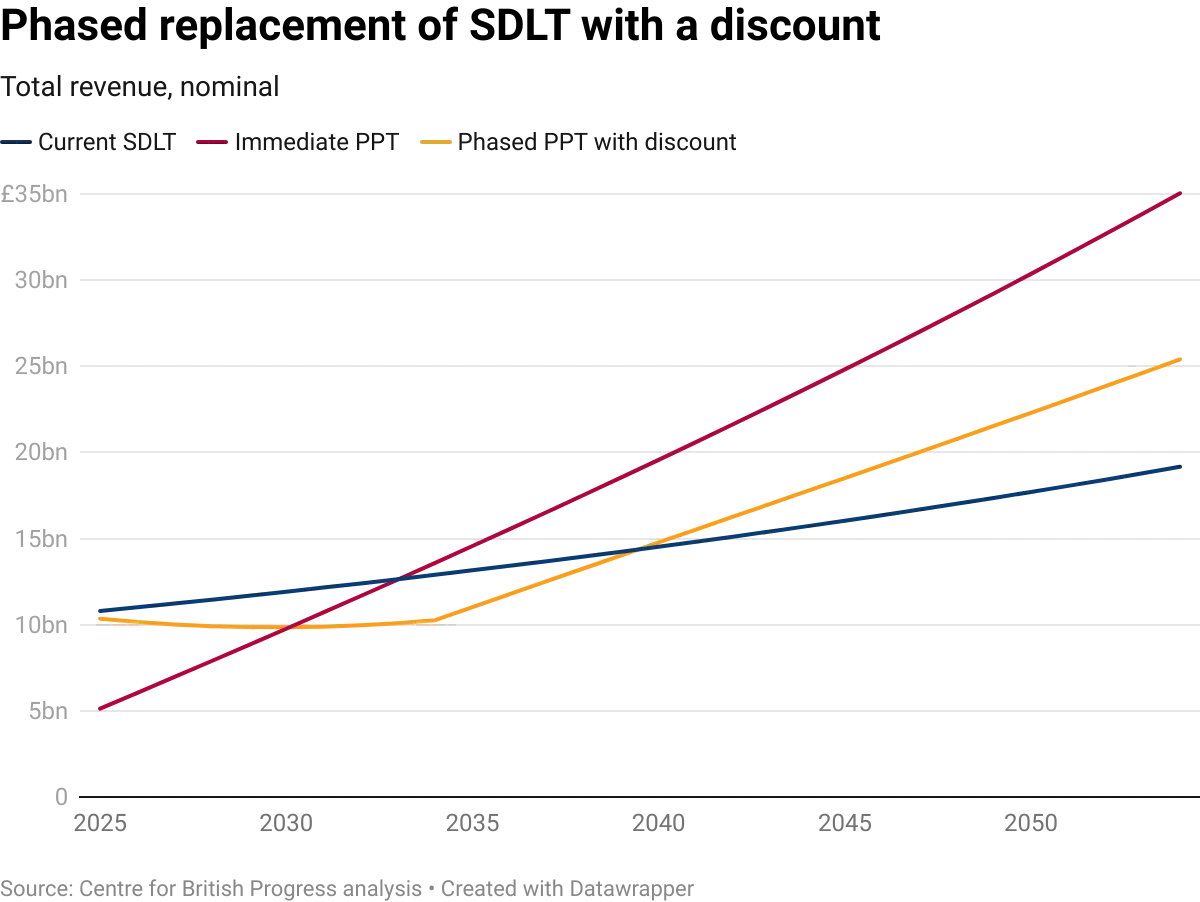

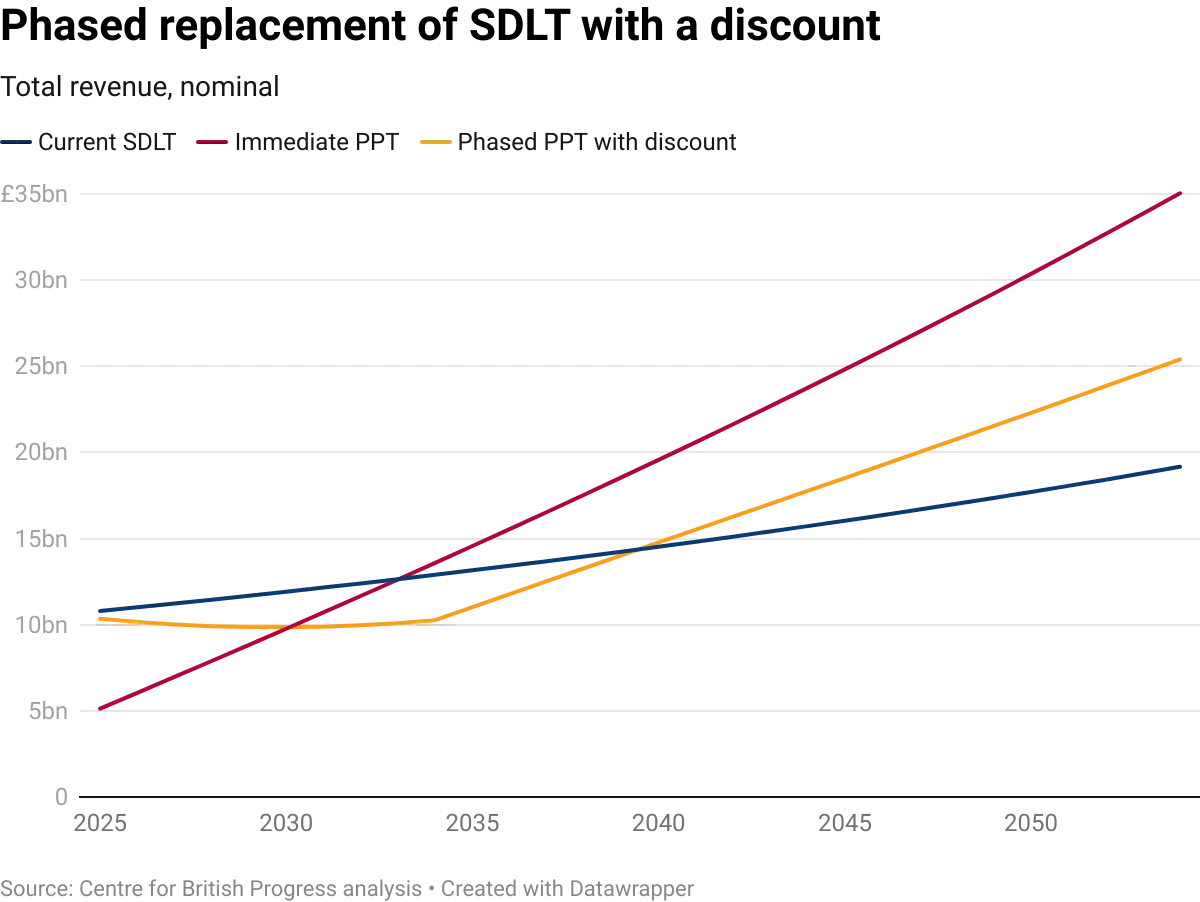

The challenge is to design an implementation strategy for a PPT which addresses the tension between immediate fiscal constraints and long-term economic efficiency. With this in mind, we consider phasing out SDLT, so the Government does not immediately lose revenue, gradually replacing it with a progressive property tax. Instead of allowing every household to transition to a new regime immediately, the government implements a phased approach to minimise the immediate impact on tax revenue.

Under this phased introduction of a PPT, buyers have the option of reducing their SDLT liability by a fixed percentage (10% in this case) in exchange for paying 10% of the new property tax in perpetuity. Each year, the portion of SDLT that buyers can opt to "switch" into PPT increases by 10 percentage points, until, 10 years after implementation, buyers have the option to switch fully out of SDLT.

This sounds complicated, but can be illustrated with a simple example. For a buyer purchasing a property worth £400,000, the standard Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) is £10,000, while the full Proportional Property Tax (PPT) liability would be £1,000 per year.

Under the first phased-in model, a buyer would be offered an annually increasing discount. In year one, this would present the following choice:

- Option A (Current System): Pay the full £10,000 SDLT upfront.

- Option B (10% Conversion): Pay a reduced SDLT of £9,000 and commit to an annual payment of £100/year (10% of the full PPT liability).

The buyer can therefore choose to save £1,000 immediately in exchange for a small, regular PPT payment. In year two, Option B would consist of a 20% reduction in SDLT and 20% of PPT, and so on, as detailed in the graph below.

Year of purchase (after policy is introduced) | Option A | Option B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

SDLT payment (one off) | Discount applied to SDLT | SDLT payment (one off) | PPT payment (annual until property is sold) | |

1 | £10,000 | 10% | £9,000 | £100 |

2 | £10,000 | 20% | £8,000 | £200 |

3 | £10,000 | 30% | £7,000 | £300 |

4 | £10,000 | 40% | £6,000 | £400 |

5 | £10,000 | 50% | £5,000 | £500 |

6 | £10,000 | 60% | £4,000 | £600 |

7 | £10,000 | 70% | £3,000 | £700 |

8 | £10,000 | 80% | £2,000 | £800 |

9 | £10,000 | 90% | £1,000 | £900 |

10 | £10,000 | 100% | £0 | £1,000 |

The graph shows us what this would mean for the Exchequer. The phase-out means that there is only a gradual loss of revenue, which then begins to rise again after 2029. In the long run, revenue is higher than SDLT, by which time SDLT is fully replaced, with all its associated economic efficiency gains.

Concerns

While the above proposals mitigate the short term decline in revenue, they would create a separate problem down the line: by pushing out losses in tax revenue further into the future, they create a shallower but longer revenue gap. This is concerning because not only does it retain an inefficient tax for longer, but it also commits a future government to accepting falling revenue.

To some extent, this is an unavoidable feature of any reform to SDLT which aims to satisfy the constraints we set above. It is impossible to keep the long term tax burden constant and prevent a collapse in revenue for the government, while moving to an annual PPT. The effect of the delayed adoption proposals above is to continue SDLT in some form for longer. Because this is designed to minimise the impact on households and give them the option of choosing the system that best meets their needs, it places the burden of adjustment on future governments.

Can financial engineering help?

Given PPT’s long run benefits and short term costs, there should be a way to transfer some of those future benefits to the present. Some form of financial engineering could, in principle, provide this. One could imagine a private company that acts as an intermediary, collecting both stamp duty and property tax revenues while guaranteeing the government a fixed annual payment. This entity could borrow from private investors and repay them with future revenue, such that investors bear the risk. The benefit would be smoothing out government revenue during the volatile transition period while transferring financial risk to private capital markets. Some gilt investors might simply switch some of their gilts to the new company's bonds; but it should also attract new classes of investors.

However, such an approach might run up against issues with ONS classification, which could make it difficult to move liabilities off the Treasury’s balance sheet. A tax collection vehicle would struggle to demonstrate the operational independence and risk transfer it needs for private classification. The ONS would likely conclude that any entity collecting taxes on behalf of the state, subject to parliamentary control over rates and policy, cannot credibly be treated as private regardless of contractual loss-sharing arrangements. Rather than solving the transition challenge, this approach might simply raise the same classification problems that have plagued other attempts to move government functions off-balance-sheet, and add more complexity.

The graph shows us what this would mean for the Exchequer. The phase-out means that there is only a gradual loss of revenue, which then begins to rise again after 2029. In the long run, revenue is higher than SDLT, by which time SDLT is fully replaced, with all its associated economic efficiency gains.

How would markets react?

Since a progressive PPT is undeniably positive for government revenue in the long run, we might expect long run borrowing costs to fall. Markets (and the OBR) may also positively score the economic benefits of a better functioning property market, including higher transaction volumes and dynamic benefits from workers moving to higher-waged jobs.

We have not sought to predict the overall impact on the current cost of borrowing. While there is a counterfactual increase in the sustainability of UK public finances, increased borrowing to cover the short-term shortfall created by the transition to PPT could place an upward pressure on yields, without the additional measures we propose below. There is currently a need to increase revenue in the short-term to prevent the Treasury from failing to meet its fiscal rules. These rules could be amended to allow more borrowing where there is a reliable mechanism for future revenue, but it is also very possible that bond markets would take a dim view of any changes to the rules. Given these risks, and the revenue shortfall projected in all forms of a progressive PPT, we propose some additional measures to boost Government revenue.

Additional measures

To address the short-term revenue gap arising from a progressive PPT, we propose two additional measures, outlined below:

1. Remove envelopment exemptions for residential properties

This is where wealthy individuals purchase homes through companies rather than personally, which allows them to avoid stamp duty when selling, by transferring company shares instead of the property. Currently, the Annual Tax on Enveloped Dwellings (ATED) charges annual fees for these corporately-owned residential properties, but only on values above £500,000, and at fixed rates that do not scale with property value beyond a maximum amount.

We propose extending progressive PPT rates to all ATED-liable residential properties (approximately 204,000 corporate-owned residential properties), which our modelling indicates could generate £0.48 billion initially, while ensuring corporate owners pay equivalent taxes to individuals over time. This would not affect non-residential properties.

2. Apply an additional rate for homes valued over £2 million

We propose an additional levy on the portion of residential property values exceeding £2 million, with a target marginal rate of 0.5% annually. Our estimates suggest this will cover approximately 164,000 residential properties at full implementation and generate around £1.5 billion in annual revenue.

For a property valued at £2,500,000, only the £500,000 exceeding the £2 million threshold would be subject to the levy. The annual cost for this excess value would be approximately £2,500 - equivalent to around £208 per month, or £7 per day. This modest contribution from high-value property owners helps fund the broader reform whilst giving households ample time to adjust their financial planning. This represents an increase in taxation relative to the current regime, but limits the necessary increase in revenue to a very small share of the property market and ensures accumulated wealth, largely driven by price appreciation in a few geographies, is appropriately taxed.

To ensure this particular measure is implemented fairly and simply, we propose two further elements. Many retired owners of expensive properties might find it hard to fund an unexpected additional contribution. For these owners, payment of the additional rate could be deferred, with the accumulated liability plus interest settled upon the property's future sale or transfer. To discourage abuse, the deferral option should be means tested and the interest rate should be set at a premium over, say, 10 year gilt yields.

Furthermore, to avoid the risk of the tax liability falling considerably short of the market value of the property, valuations would be anchored to the most recent purchase price and updated annually for local house price inflation, subject to a cap of CPI+2% with the potential for later catchup. To be conservative, we have modelled uprating annually for CPI.

Together with our base proposal of phasing out SDLT and replacing it with an annual progressive property tax (PPT), these measures would raise around £1.7bn above the current SDLT baseline in year one of implementation, rising to around £8bn annually above baseline by 2050. They would also:

- Reduce long-term borrowing costs due to forecast future revenue.

- Create more stable and predictable revenue for HMT.

- Increase productivity, GDP and tax revenue resulting from new economic activity. This includes new property transactions (which otherwise would have been made impossible due to the SDLT wedge), and dynamic effects resulting from workers moving to higher-paying jobs.

- Have no effect on the vast majority of homeowners – there are between 140k and 170k properties worth more than £2 million in England and Wales, representing between 0.55% and 0.65% of the housing stock.

- Create substantial savings for buyers, who no longer have to pay SDLT (or a reduced proportion, during the transition) on their purchases.

Appendices

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]