Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Background

- 3. The cost of living depends on income

- 4. But income fails to explain everything

- 5. Beyond the average: the role of inflation composition

- 6. Wider economic impacts of cost of living increases

- 7. How to fix the cost of living

- 8. Authors

Summary

- The cost of living is frequently cited as one of the top concerns of British households. Accordingly, and rightly, it is one of the top priorities of policymakers and this Government.

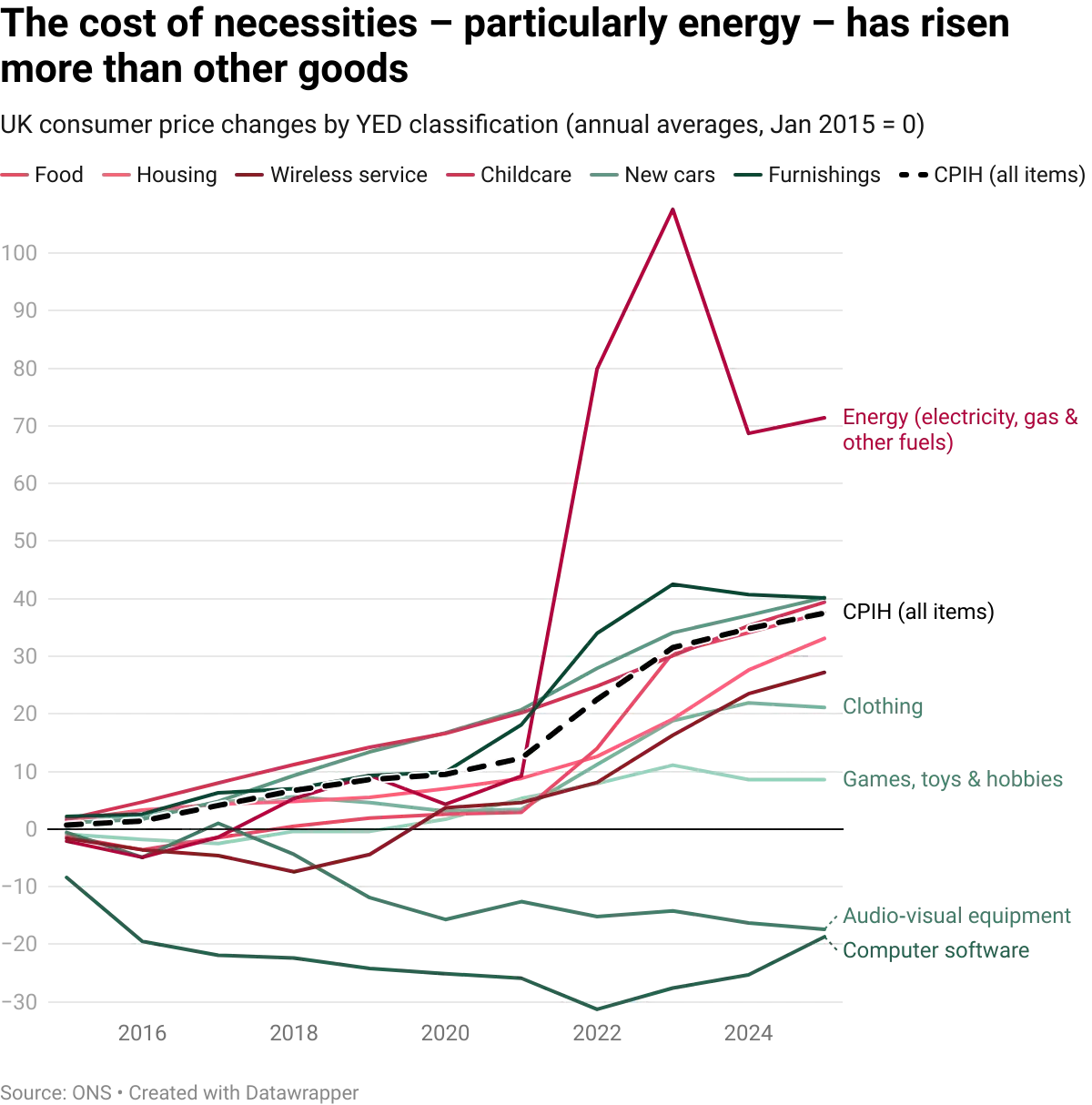

- Recent years have seen dramatic increases in the prices of basic goods (such as housing, food, energy and childcare) in absolute terms. The rise in prices of basic goods has outpaced that of ‘luxuries’ (such as electronic goods, holidays and clothing, which have in many cases become more affordable).

- It is tempting to think of concerns about cost of living solely in terms of overall inflation, and therefore addressable through interventions to reduce inflation and/or increase wages through economic growth.

- However, evidence around the demand elasticity of different goods implies that composition of inflation matters. Households feel quite differently about inflation of necessities versus luxuries.

- The higher cost of necessities has a disproportionate impact on lower income households, who are forced to spend a greater proportion of their income on necessities, and results in a greater welfare loss than a comparable increase in the price of luxuries.

- The importance of inflation composition implies that policymakers should devote comparatively more attention to the availability of basic necessities, such as housing, energy and childcare.

- This requires supply-side intervention, rather than demand-suppression to limit inflation. Dampening demand for necessities will only reduce living standards, especially as higher interest rates increase housing costs for mortgage-holders.

- Addressing this will require radical policies to boost housing supply, support energy abundance, and increase transport capacity, among wider regulatory reforms to support Britain’s productive potential.

Background

Polling consistently ranks the cost of living as one of voters’ top concerns, and this has in part driven recent government policy. Policymakers are right to prioritise this issue, though it is unclear exactly what interventions are required.

It can be tempting for politicians to call for direct price controls or proposals to suppress demand, such as through higher interest rates or lower government spending. However, both these approaches are unlikely to be effective when addressing the current cost of living crisis in the UK.

The cost of living is not just about prices of goods and services, but a reflection of the broader relationship between incomes, productivity, and the relative prices of different goods and services in any economy. The cost of living is intimately connected with purchasing power (the quantity and quality of goods and services that individuals can afford with their income) but it also depends on composition (the relative change in prices of different goods households care about).

The cost of living depends on income

The cost of living is directly and inversely proportional to the level of economic output per person produced in a country. Any reduction in real wages, and therefore household income, will be experienced as increases in the cost of living as more people struggle to maintain their levels of consumption. In short, sustained economic growth, when coupled with stable and low inflation, directly translates into higher living standards, which in turn means the cost of living becomes more manageable.

Real living standards are determined by the actual quantity and quality of goods and services that individuals and households can afford and consume. It is a measure of their purchasing power, what their income can actually buy. An improvement in real living standards means people can afford more of what they need and want, from better housing and healthcare to more leisure opportunities and greater financial security. This covers not just the volume of consumption but also its quality and diversity, reflecting actual gains in the material conditions of life.

In turn, the cost of living represents the cost required to maintain a certain level of consumption: to buy the basket of goods and services that defines a particular lifestyle or standard. Relatedly, inflation is the rate at which the overall cost of a general basket of goods evolves over time. If there is inflation, prices rise, and the cost of maintaining the same lifestyle might go up because more money is needed to purchase the same items. On the other hand, deflation (a general fall in prices) would mean the general cost of buying the same things has decreased.

Prices, on their own, give us an incomplete picture of affordability. A cup of coffee may cost €3 in Dublin and €1.50 in Rome, but it would be wrong to conclude that coffee is therefore less affordable for Irish than Italians, as incomes are so vastly different (average take home pay in Dublin is twice that in Rome). When we adjust wages and incomes for the overall cost of the things the average person buys, these are real wages and incomes, that is, the actual basket of goods that people can afford - not their monetary value.

Real income constitutes a true measure of purchasing power. If an individual’s income increases by 5% in a given year, but the general level of prices, as measured by an inflation index like the CPI, increases by 10%, their real income has gone down. Despite earning more pounds, the consumer may find it harder to afford the same things as before. This would be felt as an increase in the cost of living - it is now harder (if not impossible) to continue to afford the same things. Economic growth in real terms, which is by definition an increase in the ability to purchase goods and services, is therefore intimately linked to how high the cost of living is, not just how it feels.

But income fails to explain everything

The above analysis aims to move the cost of living debate beyond prices to factor in incomes, and therefore the real purchasing power of households. However, this is insufficient in explaining recent and ongoing public dissatisfaction with the cost of living, which may in turn be a driver of success among populist parties.

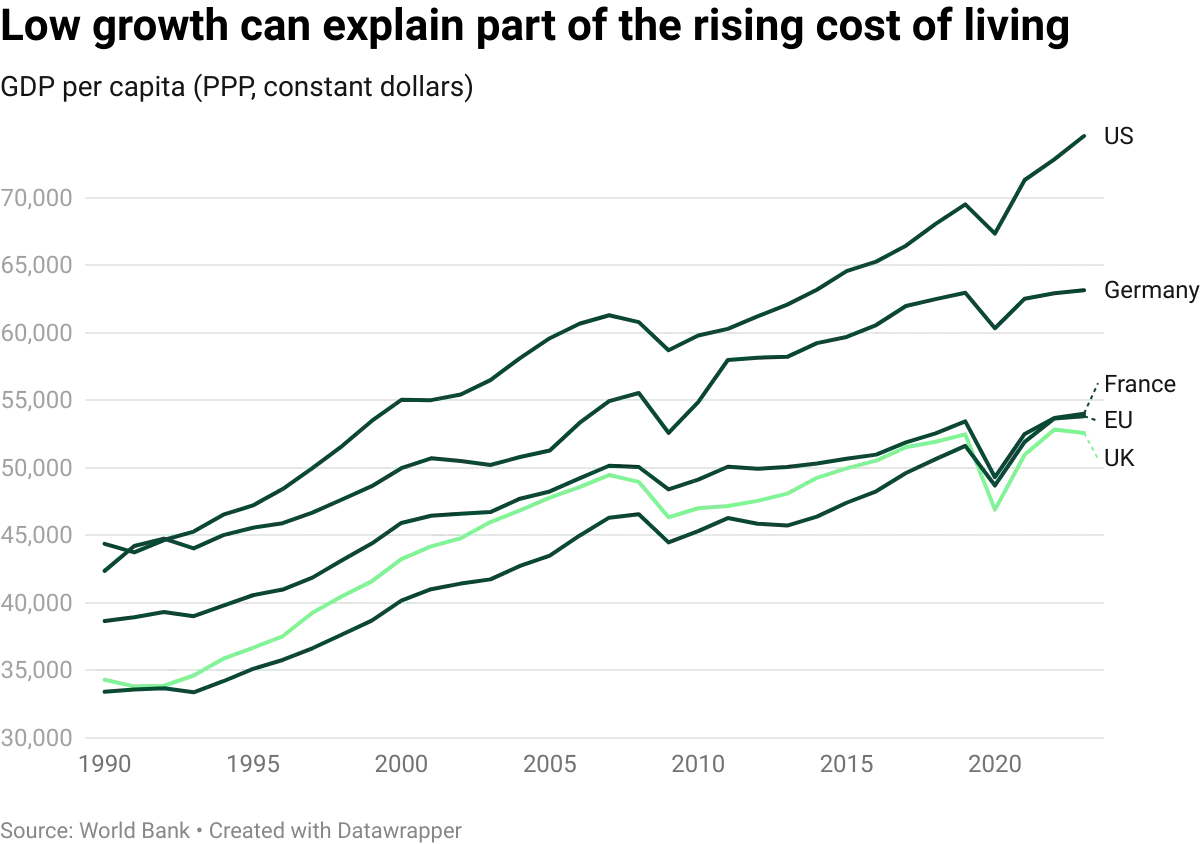

In the UK and other European nations, stagnating productivity and incomes since the financial crisis may explain this phenomenon: no growth alongside high inflation means standards of living erode, which is to say a higher cost of living.

But this explanation is unsatisfactory. First, because while incomes in many European countries (including the UK) have been stagnant since the great recession, associated political dissatisfaction appears to have materialised more recently. Second, public disaffection and increased populism have been seen and felt across a range of countries with relatively high growth rates, from Eastern European countries that have been converging on average EU income to countries on the European periphery that have experienced recent periods of sustained growth and even countries for whom the great recession or the pandemic appear to be statistical blips in GDP data.

A lack of growth is therefore insufficient to explain why the public have become increasingly concerned about the cost of living, and any associated political implications. While the real income story plausibly accounts for some of the dissatisfaction expressed by the public, it cannot offer a complete account of why this remains the most important pressing concern. In many countries, living standards are objectively improving at a noticeable rate, but why does it feel to many people like they’re struggling to get by?

Beyond the average: the role of inflation composition

While real incomes – wages which take into account prices – are a reasonable guide for how households experience the cost of living, incomes fail to fully capture the nuanced and often deeply personal reality faced by individual households. The overall price level, which is what we refer to when we talk about inflation, is an average built from the changing prices of hundreds of different goods and services, each weighted according to how much a ‘typical’ household spends on them.

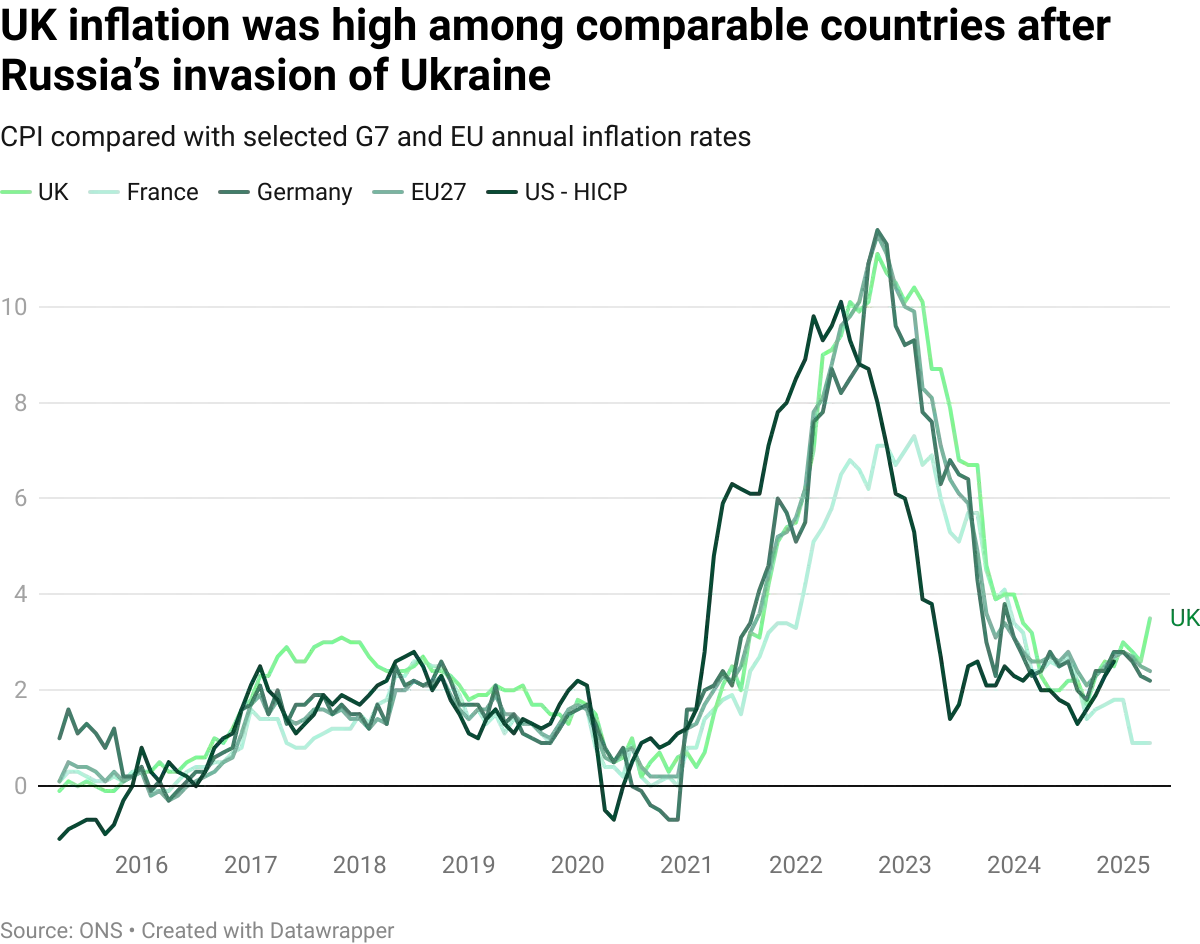

Inflation across Europe spiked in the aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and while it has not been felt everywhere to the same extent, the rapid and generalised increase in headline prices has certainly played an important role in driving public concern about the cost of living.

However, households do not consume an “average” basket in precisely those proportions, nor do they experience an “average” price increase. They purchase specific goods and services, and the price changes of these individual items can vary significantly.

A key factor here is the income elasticity of demand of different products. This is a measure of how much households change their consumption of different types of goods in response to changes in real income. When the elasticity is higher than 1, households will spend increasingly more on a good or service as their income rises. These can be described as luxuries, goods and services you would only spend on when the basics have been covered. Goods and services with an elasticity of less than 1 are best described as necessities, and people tend to spend less, as a proportion of their total spending, on them as their incomes increase. Very roughly, we can categorise them using the following table:

Demand elasticity for different types of goods

Category | Typical income-elasticity (ε) | Adjustment options when price rises |

Necessities – housing, energy, weekly groceries | Low (< 1) | Hard to cut, must be purchased to get by |

Luxuries – holidays, high-end electronics, dining out | High (> 1) | Can be postponed, substituted, or skipped |

Recent years have seen stark differences in the price changes of different goods and services.

In the graph above, we have roughly categorised the various components of CPIH (the standard measure of inflation which includes housing costs) according to whether they should be considered luxury spending items in greenblue (ε>1) or necessities in red (ε<1). All of the items classified as necessities have had their price increase around or above the level of domestic inflation, while many of the items classified as “luxuries” have seen their prices well below the level of inflation.

The graph shows a generalised phenomenon of luxuries becoming slightly more accessible while necessities have become more expensive. This is somewhat in contrast with earlier economic growth in rich countries, where necessities became comparatively more affordable, so that households were able to spend a falling proportion of their income on the basics. Since these are goods with lower demand elasticity, the result is favourable for households: they feel richer, as they have more money available for discretionary spending.

The above shows that while both growth and inflation matter (and both have given households reason to be unhappy over the last decade, particularly in the UK), the composition of inflation could explain the acute public dissatisfaction with the cost of living. While inflation has recently increased, not all items experienced the same level of inflation, and households experienced a more acute decline in their ability to pay for the essentials, contributing to a generalised feeling that the cost of living has increased considerably.

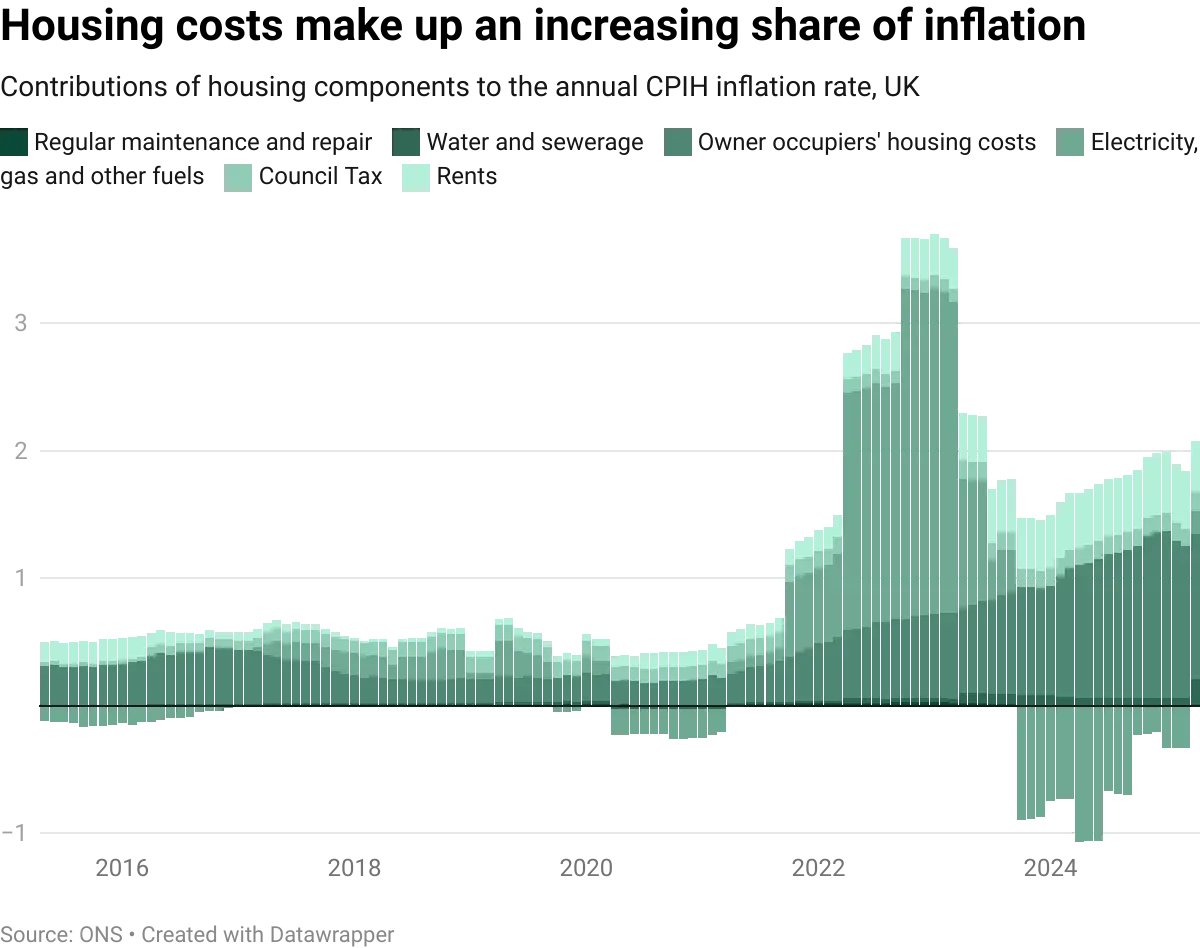

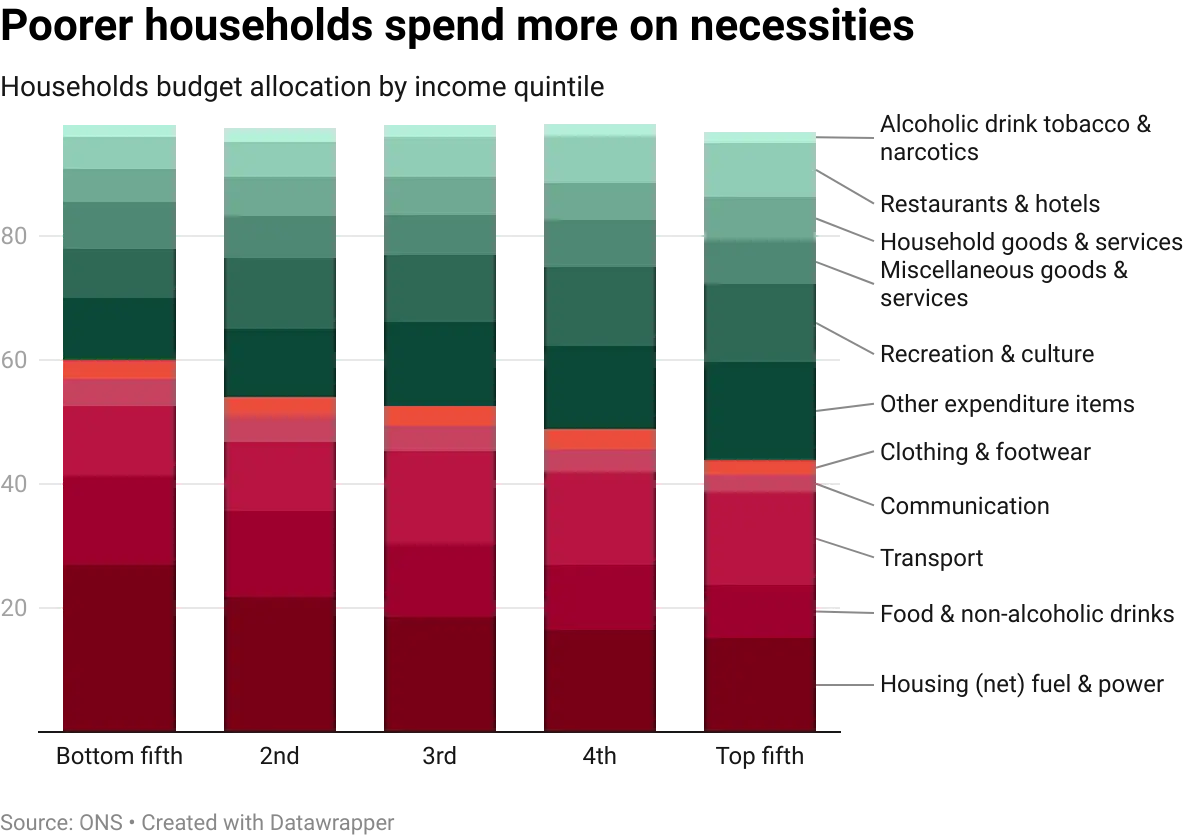

Changes in the composition of inflation can also have distributive implications for society and affect overall inequality. Poorer households spend a greater proportion of their income on basics, and therefore will experience a greater squeeze in real income, relative to richer households, who can now enjoy comparatively cheaper luxury goods. These cost pressures have become much more salient in recent years, with the proportion of household spending allocated to housing and energy having increased from 13.7% of household spending in 2016 to 18.6% in 2023.

That increase disproportionately hit the poorest households in the country. In 2023, almost 27% of the expenditure of these households were allocated to this spending category, while the richest households spent only 15.2%. This data supports both the economic intuition that people will spend a smaller fraction of their incomes on necessities as they become richer, and also the fact that recent price increases were felt primarily by the lowest income households. Not only do richer households spend a lower fraction of their income on basic needs, but they almost certainly enjoy a higher standard of these necessities; aggregate spending figures do not account for the significant differences in the quality of housing or level of comfort.

In recent years there have been two clear drivers of UK inflation. In 2022, the story was almost entirely one of high energy prices, caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The disruption of gas supply to the European market meant that an increasing share of the UK energy market was driven by domestic supply. The UK is undergoing a deep structural transformation of its energy base, moving away from fossil fuels and towards cleaner sources. This transition has happened against a backdrop of relative energy scarcity. For long periods, such as when the wind isn’t blowing, the UK is relatively exposed to having the price of energy set by the least expensive marginal producer, which tends to be gas.

A lack of abundant energy supply means that any disruption to expected patterns of supply will inevitably result in shortages, which push up prices for long periods of time. While relatively abundant renewable electricity is available during certain periods, wind and solar power cannot, without further progress in energy storage technology, provide power to meet demand at all times while keeping prices low, due to weather variations. For that we must also take additional steps.

The second significant driver, which represents a deeper, structural problem in the UK economy, is the contribution of housing costs to inflation. Since the middle of 2023, this has been the largest contributor to the domestic component of inflation in the UK, and unless there is a substantial acceleration of homebuilding in the most constrained parts of the country, there is little reason to expect this pressure on inflation to abate.

Increases in housing and energy costs directly affect households, particularly those on lower incomes, and are clear examples of necessities with low demand elasticity. This means that households feel the impact of price increases more acutely. Housing and energy are also both representative of the significant supply constraints faced by the British economy, which highlights another mechanism by which energy and housing costs can hurt households: since energy and rents are inputs to other productive processes, they also have much more significant pass-through to the rest of the economy. UK producers face higher energy costs, while companies and shops face higher rents for retail and office space. This is often passed on to consumers in goods and services.

Wider economic impacts of cost of living increases

Supply chain impacts

The consequences of this differentiated inflation, characterised by rapidly rising costs for necessities, extend beyond the budgets of UK families. The two notable drivers of headline inflation in the UK since 2015 – energy and housing costs – have impacted core inflation, which aims to track persistent trends in prices, despite this measure excluding more volatile goods including food and household energy bills. This is because energy costs can filter through to core inflation as firms face higher input costs. Industrial users are particularly reliant on energy, while higher rents affect everyone, and could encourage some businesses to locate their activities in suboptimal places.

When an input to production becomes scarcer, companies and households that use it in either production or final consumption bid up its price. This typically reflects a higher underlying cost of production: it is simply more expensive to get that input than it was before. For both households and companies, this means difficult choices: budgets have to be stretched and cuts be made elsewhere. Businesses often also have to either increase the price of their own products or make fewer profits, which in turn reduces their capacity to invest in expansion or new activities. As a result, the increase in the cost of the input leads to a reduction in the economy’s real productive capacity: we simply do not have as many inputs as we did before, and must produce less as a result.

Energy costs have a direct impact on firms. Manufacturers face higher electricity and fuel costs for running machinery, processing raw materials, and transporting finished goods. Logistics and distribution networks become more expensive to operate, impacting the cost of delivering goods to market. Service sector businesses, from retail outlets and restaurants to offices and financial institutions, incur higher expenses for heating, cooling, and lighting their commercial premises. Cloud servers, on which an increasing share of the economy depends, are particularly energy intensive.

These increased business costs, if they cannot be absorbed through efficiency gains, are frequently passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices for a wide range of final goods and services. This can potentially trigger a broader cost-push inflationary spiral throughout the economy, where initial price shocks in key input sectors ripple outwards, leading to more generalised inflation. UK firms find themselves at a competitive disadvantage to foreign companies which can enjoy cheaper energy.

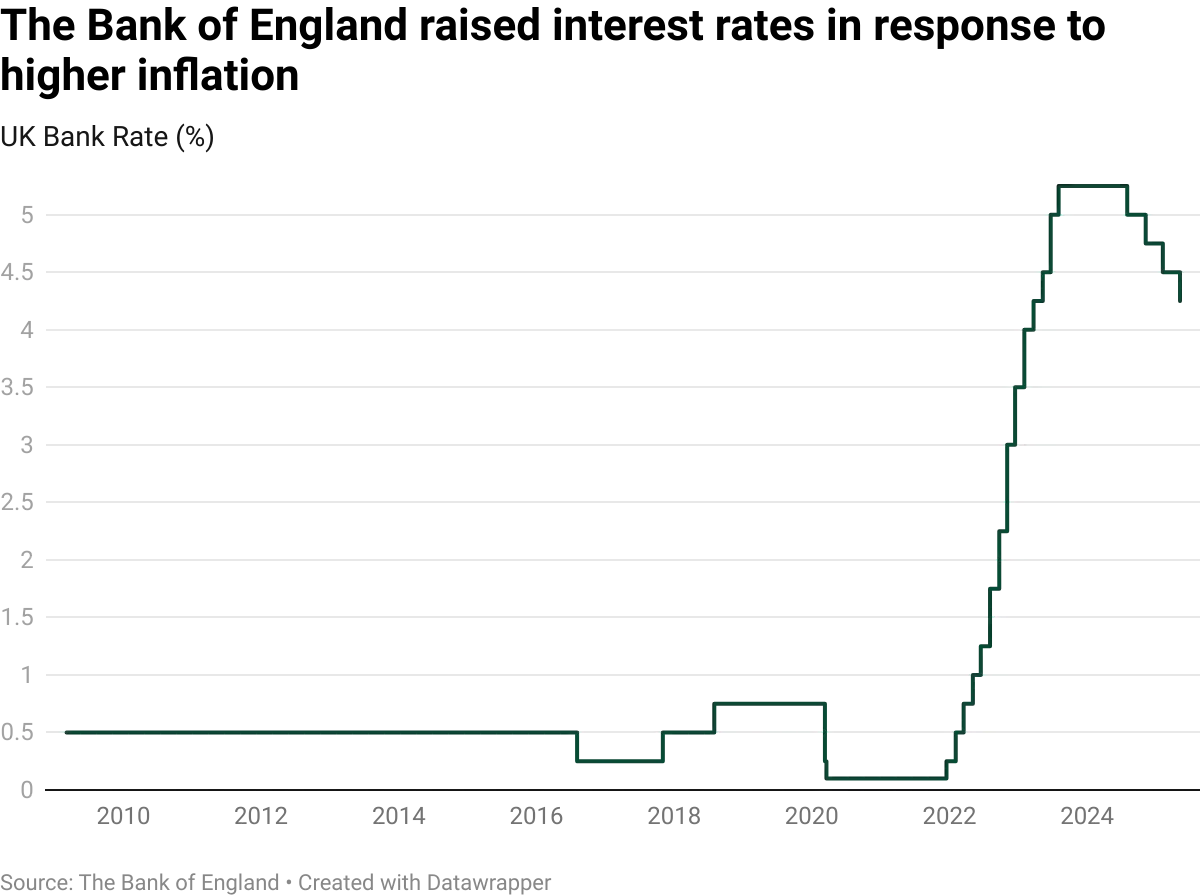

Macroeconomic policy

As inflation increases, governments and central banks will intervene to manage expectations around inflation. There is evidence that the expectation of high inflation can drive inflation, as workers, businesses and households expect prices to rise faster, so it is important for public authorities to ensure they respond quickly to control inflation. In 2022, concern about the path of inflation, and particularly the domestic contribution to this inflation, led the Bank of England to increase interest rates.

Domestic cost-push inflation significantly complicates the Bank of England’s task, compared to demand-led inflation. Increases in interest rates primarily impact the economy through demand suppression, which does not address the root cause of inflation. Because the central bank cannot make inputs more abundant, it is effectively forced to effectively reduce economic activity to reduce inflation.

Macroeconomic consequences

If the Bank of England raises interest rates, the primary and most immediate impact for households is higher borrowing costs. For the significant proportion of homeowners with mortgages, especially those on variable-rate products or whose fixed-rate deals are maturing, this means higher monthly mortgage payments, as many households experienced in the aftermath of the Truss administration’s mini-budget crisis.

Faced with the dual pressure of higher absolute costs for essential goods and services (particularly housing and energy, as discussed) and increased outgoings for debt servicing (particularly mortgages and credit card repayments), households are forced to further reallocate spending away from “luxuries” to afford the increased cost of necessities.

As a result, spending on more discretionary, higher-elasticity goods and services is curtailed. This includes hospitality (restaurants, pubs, hotels), leisure activities (cinema, theatre, sports), cultural pursuits, non-essential retail purchases (new clothing beyond basic needs, home furnishings, gadgets), and major durable goods acquisitions like new cars or significant household appliances.

This “displacement effect” can lead to an observable slowdown in economic activity within these consumer-facing sectors, reducing turnover, profitability, employment levels, and future investment plans. Moreover, a sustained fall in discretionary spending, coupled with heightened financial anxiety and uncertainty about future economic prospects, can significantly depress overall consumer confidence. This, in turn, can trigger precautionary saving as households attempt to build a financial buffer against perceived future hardships, further dampening aggregate demand and potentially prolonging periods of subdued economic activity or even contributing to a recessionary environment.

Third, beyond these demand-side effects, chronic undersupply or excessively high cost of essential goods and services can directly restrict the economy’s potential output. Potential output refers to the maximum level of production an economy can sustainably achieve without generating undue or accelerating inflationary pressure.

This is most evident in housing. A persistent and severe shortage of affordable housing acts as a substantial constraint on labour mobility, particularly in economically dynamic regions and major urban centres where job creation is often strongest. When housing is scarce, it becomes prohibitively expensive or practically impossible for workers to relocate from areas with fewer job opportunities to those where their skills are most in demand or where new employment opportunities emerge. This geographical mismatch between labour supply and demand can result in skills shortages and unfilled vacancies in some places while there are pockets of unemployment or underemployment in different parts of the country. The result is a suboptimal allocation of the nation’s labour resources, which reduces overall productivity growth and can exacerbate regional economic inequalities.

Similarly, an energy system that is characterised by unreliable supply, or one that is simply too expensive, can act as a major deterrent to both domestic business investment and foreign direct investment. Firms, particularly those in energy-intensive manufacturing sectors such as chemicals, steel, or ceramics, may find it difficult to compete on a global scale, may postpone or cancel investment plans in new plant and machinery, or may even choose to relocate production facilities to countries with more favourable and stable energy cost structures (or not invest in the UK at the outset).

These are not merely cyclical issues that tend to resolve themselves with the natural ebb and flow of the economic cycle; they represent deep-seated structural impediments that systematically lower the long-term growth trajectory, productivity performance, and international competitiveness of the UK economy. Addressing these bottlenecks in the supply of essentials is therefore crucial not just for household welfare but for the health of the entire UK economy.

Impacts for HMG

The macroeconomic consequences described above have further implications for the Government – and therefore public services – in the form of reduced tax revenue, and increased payments due to unemployment benefits and other kinds of counter-cyclical support. It also worsens the debt problem by increasing the debt to GDP ratio: the Government still owes the same, but can now generate less income through taxation.

Furthermore, higher interest rates mean more expensive debt repayments for the Government as well as ordinary households, and increases the payments on reserves the Bank has to make to financial institutions to keep the amount of money in circulation under control - an amount that is then directly backstopped by the government. Although inflation reduces the real value of Government debt, in this instance, inflation is not the result of increased spending pushing up prices, but a consequence of chronic undersupply of key inputs to economic activity. The inevitable consequence of that is to place increasing strain on the Treasury to manage the fiscal implications of inflation.

How to fix the cost of living

Addressing the cost of living crisis requires a far more complex set of interventions than managing demand through either price controls or contractionary fiscal or monetary policy. It is essential to address the underlying causes of higher cost of living, which are on the supply side of the economy, and primarily felt in the cost of necessities, particularly housing and energy. The costs of these particular inputs have a disproportionate impact on inflation, and increase costs throughout the economy.

Fundamentally, the cost of living crisis is the result of a chronic lack of abundance. If we prioritise achieving other goals over boosting our productive capacity, households will continue to feel squeezed in their everyday spending, and we will see increasing public dissatisfaction. Paying the rent, keeping the house warm and covering basic bills feel increasingly more difficult, especially as incomes stagnate in real terms.

Meanwhile, wider economic activity has to contend not only with higher input costs, but also with suppressed demand as households have to make budget cuts. The government also feels the pressure to reduce its own spending, and the burden of servicing the debt puts additional strain on an already difficult situation.

Abundance is the solution to scarcity

It may seem odd to say that the public is concerned about both the cost of living and real income. After all, one is the mirror image of the other: if real incomes rise, households can afford more, so the cost of living is effectively smaller.

But this is not the whole story, because how households are affected by the cost of living depends on which goods and services see inflation. Even if living standards are generally stable and wage growth is in line with inflation, the composition of inflation matters. In recent years, households have seen dramatic increases in the cost of housing and energy, two of the most fundamental necessities. This has forced deeper cuts to all discretionary spending. The demand elasticity of necessities versus luxuries implies that households would much rather decrease their share of necessities as they become more affluent, so having to spend a greater share of income on the basics feels like becoming poorer. Furthermore, this compositional change disproportionately affects lower income households, who already spend a greater share of their income on necessities, and are therefore made directly worse off.

Add to this, inflation and living standards have not been stable in recent years, particularly in Britain. Inflation has often outpaced wage growth, leading to falling real incomes, and productivity has been stagnant. Even though the original price shock was driven by an external event– Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine –, it has had a significant knock-on effect for domestic UK inflation. Concerns about inflation also force the Bank of England to respond through higher interest rates, further reducing economic activity and constraining the Government’s fiscal headroom.

Britain is suffering a cost of living crisis because we have a supply-side crisis: we do not produce enough low-cost and reliable energy, and we do not have enough homes in the right places. The very best fiscal and monetary management cannot overcome the increasing constraints that we have placed on ourselves by restricting production in those places where demand is greatest.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]