Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. The Challenge

- 3. The Opportunity

- 4. Plan of Action

- 5. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- 6. Authors

Summary

- Geospatial data is critical to modern infrastructure, underpinning everything from emergency services to digital commerce. But the UK imposes an "innovation tax" on key geospatial datasets, restricting access through costly licenses and bureaucratic hurdles.

- Essential data, such as addresses, is locked behind ineffective commercial models, stifling innovation, slowing economic growth, and complicating public service delivery.

- The root cause is that the UK’s geospatial institutions, like Ordnance Survey and the Royal Mail, have been told to run themselves as businesses that create short-term revenue from selling data. In a striking paradox, taxpayers both fund the original data collection and subsidize these struggling private firms, while simultaneously being denied free access to the very data they helped create.

- Unlike the UK, many high-income countries recognise geospatial data as public infrastructure and have made it freely available, fuelling technological and economic advancements.

- The EU has mandated free access to high-value geospatial data, unlocking billions in economic value, while countries like Australia, Denmark, France, and the Netherlands have already embraced open data policies.

- The UK’s model discourages competition, inflates costs, and hinders industries reliant on accurate mapping and address data. Reforming the UK’s geospatial institutions is essential to modernising public services, supporting businesses, and maintaining global competitiveness.

- The government should integrate geospatial data into the National Data Library and remove unnecessary licensing barriers to drive innovation and growth.

The Challenge

While most developed nations provide free access to geospatial data, treating it as essential public infrastructure, the UK remains an outlier. Key datasets, including mapping and address data, are locked behind fees and restrictive licensing agreements, making them less useful for businesses, startups, and public services. This paywall has become an artificial constraint on innovation, restricting competition and limiting the full economic and societal potential of the country’s geospatial assets.

Institutions like Ordnance Survey and Royal Mail have been instructed to act as commercial entities, prioritising short-term revenue over long-term public benefit. This approach has placed an "innovation tax" on businesses, local governments, and researchers who rely on accurate, up-to-date geospatial data. Instead of fostering economic growth and technological advancements, these policies have created financial and bureaucratic burdens that slow progress and discourage new entrants into the market.

Geospatial data is Critical National Infrastructure

National maps were created by the administrative state for public and state benefit. Over the centuries institutions like the Ordnance Survey, the Land Registry, the British Geological Survey, and the Royal Mail took on a broader role to also support commercial processes. Today, the digital world has made geospatial data a fundamental part of national infrastructure, influencing sectors from logistics and e-commerce to urban planning and emergency response. OpenStreetMap, for instance, has become a valuable global resource used by individuals, businesses, and governments to maintain collaboratively generated geospatial data. This open ecosystem supports billions in economic value, as platforms like Google Maps, Apple Maps, and Facebook integrate its freely available data.

Recognising the importance of geospatial data, the UN classifies it as critical national infrastructure essential to achieving Sustainable Development Goals. The EU has designated geospatial data as high-value, requiring member states to provide it for free and estimating that such policies will generate up to €2 billion annually in economic growth by 2028. Countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark, and France have already embraced this approach, removing financial and administrative barriers to access the data. The Dutch government, through its Digital Government Act of 2023, has committed to making high-value datasets such as address, mapping, and land parcel data openly available, benefiting businesses, public services, and researchers alike.

The UK Imposes an Innovation Tax on Geospatial Data

The UK, however, has taken a different path. Instead of treating geospatial data as a public good, it has commercialised access, limiting its availability and slowing innovation. The privatisation of publicly collected data has resulted in profit-seeking entities controlling key datasets, imposing high costs and licensing restrictions that prevent efficient use. In a striking paradox, taxpayers both fund the original data collection and subsidize these struggling private firms, while simultaneously being denied free access to the very data they helped create.

The costs can be high. A licence for the Royal Mail’s Postcode Address File (PAF) will cost an organisation £21,600/year. Ordnance Survey’s AddressBase Premium, which contains PAF and additional data about historic and to be developed addresses, costs £150,000/year. And Ordnance Survey’s MasterMap, which shows the topography of the UK, can cost over £5m. For an innovator looking to create a new food delivery service, a tool to help developers decide where to build houses, or a service to help farmers decide which food to grow on their land these prices are prohibitive. They can spend more time negotiating a reasonable arrangement for access to the data than they do developing their products.

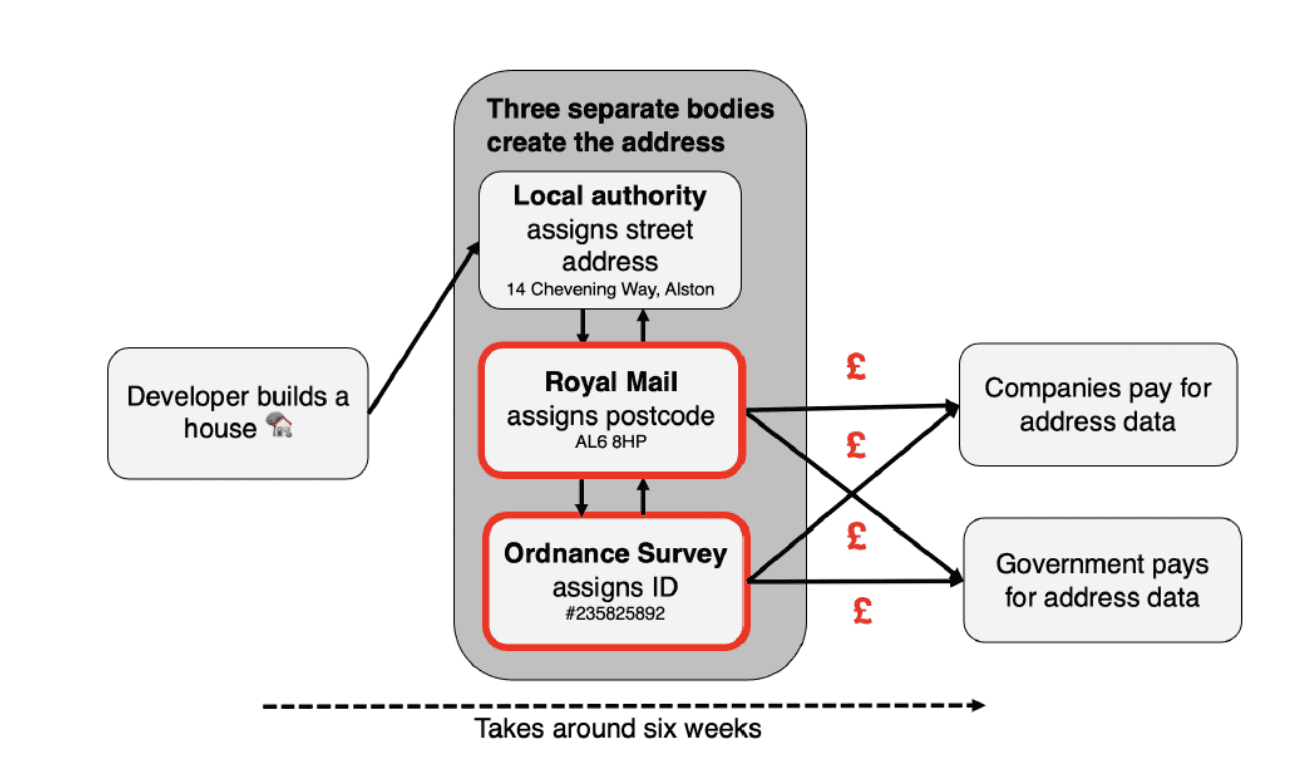

Taking one example in detail. Address data is created by local authorities as part of their statutory duties. Unique Property Reference Numbers (UPRNs) are allocated to local authorities by Geoplace, and postcodes are added to addresses by Royal Mail. Geoplace performs quality controls across the overall process and system. However, this essential data is then aggregated into two large datasets: the Postcode Address File (PAF), controlled by Royal Mail, and AddressBase, controlled by Ordnance Survey.

Figure 1: A Simplified Overview of UK Address Maintenance Processes

Source: the Centre for Public Data. For a more detailed explanation read Owen Boswarva’s primer.

Privatisation of these services did not work. In 1999, OS was turned into a trading fund, and in 2015, it became a government-owned limited company. This shift forced OS to act as a commercial entity rather than a public service provider, requiring it to compete with global tech firms while still managing essential national geospatial data. Despite these changes, OS has struggled to build a significant international business, with nearly 60% of its revenue still coming from UK government contracts. Instead of flourishing as an independent, competitive enterprise, OS remains reliant on taxpayer funding while restricting access to data that could drive wider economic benefits.

Similarly, the UK’s Postcode Address File (PAF) was sold along with the privatisation of Royal Mail in 2013. Royal Mail has faced significant financial difficulties following privatisation, recently requesting the government to reduce its postal delivery obligations while simultaneously negotiating a potential sale to an overseas buyer.

This issue extends beyond these core datasets. Under sui generis database rights, Ordnance Survey and Royal Mail may hold intellectual property rights over datasets derived from their national address databases. One example is the Land Registry’s Price Paid Data, a dataset that helps individuals and developers understand property prices and plan construction projects. While the government aims to make this data openly accessible under the Open Government Licence, its inclusion of addresses entangles it with Royal Mail’s licensing restrictions. As a result, startups and businesses hoping to use this data must negotiate with Royal Mail, pay a licence fee, and justify their intended use—turning what should be open data into a restrictive system.

The negative impact of these restrictive data policies also affects public sector delivery. Local authorities, government agencies, and public services that rely on accurate geospatial data for planning, emergency response, healthcare delivery, and infrastructure development face unnecessary hurdles.

The Opportunity

The UK government has a clear opportunity to unlock economic growth and technological innovation by mandating the release of address and mapping data as open data. By making address and mapping data openly available, the government can remove the barriers that stifle competition, reduce inefficiencies in public administration, and support the development of new industries. Rather than allowing key national datasets to be controlled by institutions focused on revenue generation, the UK should follow the example of other leading economies and treat geospatial data as a public asset that benefits everyone.

Other leading economies have already embraced this approach. In 2023, the EU required its member states to make high-value datasets—including street addresses and key geospatial and meteorological data—freely available to support entrepreneurship and SMEs. Australia, New Zealand, and the United States have implemented similar initiatives, while Denmark and France made their national address data openly available in 2005 and 2015, respectively. In all these cases, governments provide address and geospatial data as a public service, funded by general taxation. The UK now stands as an outlier among high-income nations in failing to adopt a similar strategy.

How Will This Help Growth?

Making geospatial data more accessible would lead to immediate economic benefits. Unlike personal data, geospatial data is non-sensitive and already exists, meaning it can be used without requiring the creation of new datasets. The UK’s existing geospatial industry is well-positioned to capitalise on reduced barriers to access, accelerating innovation and investment.

International examples highlight the economic potential of open geospatial data:

- In 2009, the United States made Landsat satellite imagery openly available, generating $1.8 billion in economic value per year within two years.

- In 2010, Denmark reported that publishing open address data created €14 million in annual economic benefits.

- The EU estimates that by 2028, the wider availability of geospatial data - including addresses and maps - will generate up to €2 billion per year in economic growth.

A similar shift in the UK could unlock hundreds of millions in economic value within a few years of implementation.

Opening access to geospatial data would also generate cost savings across the public and private sectors. Currently, thousands of businesses and public bodies must manage licensing agreements and payment structures to access geospatial data. Removing these barriers would immediately reduce administrative overheads.

For example, the Royal Mail’s Address Management Unit (AMU) maintains the PAF at an average cost of £30 million per year. This dataset undergoes 600,000–700,000 updates annually, translating to a cost of £40–£50 per change. Given that Royal Mail’s primary role is to allocate postal delivery codes to addresses created by local authorities, these costs are disproportionately high. A significant portion of these costs likely arises from licensing and commercial agreements rather than actual data management. By integrating address data into a centralised, open system, these costs could be substantially reduced.

New industries and services also often emerge when key datasets become freely available. While it is difficult to predict every application, historical examples provide insights. The rise of GPS-enabled technology revolutionised personal navigation, ride-sharing, and location-based services. Transport for London’s decision to open its data transformed how people navigate the city, leading to the development of widely used journey-planning applications, saving time for millions of passengers and creating jobs in London

Given recent advancements in autonomous technologies, making the UK’s geospatial data freely available could accelerate the development of driverless cars, drone delivery systems, and next-generation logistics solutions.

Plan of Action

The following simple steps outline a practical plan for reform:

- Make Address Data Fully Open – Task the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology’s (DSIT) National Data Library team with making the address data produced by local authorities freely and openly available within 12 months. This includes ensuring that all licensing restrictions are removed, and the data is published in a format that maximises accessibility and usability.

- Buy Back the Postcode Address File (PAF) – The Department for Business and Trade (DBT) should negotiate and acquire the rights to the PAF from Royal Mail and allocate its management to the National Data Library. This will eliminate existing licensing restrictions and ensure that postcode data is freely available for public and private sector use. Public and private sector delivery teams will then be able to move quickly to unlock the additional value that adding postcodes to local authority data can provide.

- The UK government has previously estimated it would cost £487m to buy back the rights to PAF. This estimate is unreasonable. Using a discounted cash flow valuation with a discount rate of 5.5%, a risk of obsolescence of 1% and strong negotiating tactics from the government we expect the actual figure to be below £100m. To minimise ongoing maintenance costs the task of allocating a postcode should be given to local authorities and incorporated into their existing address management function.

- Transform the Ordnance Survey (OS) - The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) should help the Ordnance Survey change its business model to fully embrace open data. Other countries, such as the Netherlands Kadaster agency, provide models that can be learned from. The next datasets to be released as part of this transformation should be AddressBase Premium and MasterMap.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is this personal data?

No. Address data and maps are about places, rather than identifiable individuals. It tells us where people might live, but not who lives there. The exception is if a business is named after an individual, an address is named after the business, and the individual lives or works at the same address as that business

Won’t all the value flow to large firms?

Not necessarily. Large firms can already afford to pay the innovation tax or, in many cases, to collect their own geospatial data through the services they provide. By making geospatial data available for free governments can help level the playing field, allowing smaller organisations to compete on providing services that use the data. Opening up the public sector’s data can also reduce biases in the data and unfairness in outcomes. The public sector’s mapping institutions will map the whole country, while the data held by large firms may focus on medium and big cities where there is a larger market of customers. The EU’s rationale for opening up address data is primarily to support entrepreneurship and SMEs.

Is there a single source of truth for geospatial data? Will releasing the public sector’s data simply crowd out private sector activities?

No. There are many forms of addresses, many ways to map places, and many different levels of detail that geospatial data can be taken to.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]