Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Challenge & Opportunity

- 3. Plan of Action

- 4. FAQs

- 5. Authors

Summary

- The government has now formally announced the creation of a new Regulatory Innovation Office (RIO), a much-needed institution to unlock investment and innovation to support UK growth.

- Although the RIO is only in its initial phase, the government has not yet provided many details about how it will work – this is not a good signal about HMT’s commitment to this issue. It is critical that the RIO is not just the next iteration in a long line of failed regulatory reform initiatives, but leads to a genuine stepchange in pace, urgency and delivery to fulfil its intended potential.

- To succeed where others have failed, the government needs to be clear about the problems it wants the RIO to solve, and make the correct choices about i) structure, ii) scope, iii) budget, iv) leadership, and v) priorities to deliver on this ambition. In effect, the government needs to ensure the RIO has clear focus and is genuinely empowered to succeed.

- To ensure the RIO is focused, we recommend:

- A dual mandate of unlocking new sectors and upgrading existing markets. This means enabling frontier, disruptive innovation in emerging areas of technology, such as cultivated meat or AI in healthcare, as well as promoting innovation in existing, mature regulated sectors, such as financial services or pharmaceuticals.

- Working on selected priority sectors/technologies that respond to market demand but also align with industrial strategy priorities, alongside its work on more general regulatory performance.

- To ensure the RIO is empowered, we recommend:

- Agreeing an up-front, flexible, £100m fund to be allocated towards regulatory innovation

- Appointing an external Chair to give the RIO greater heft

- Close involvement of the Treasury and Number 10 to give the RIO backing in its dealings with regulators

Challenge & Opportunity

Fixing the UK’s regulatory environment is essential to unlocking innovation in the sectors that most affect people’s lives – they are regulated markets for a reason – and driving much-needed investment and economic growth.

Regulatory innovation is crucial for the UK as it seeks to remain competitive in the global economy. The UK cannot and should not always compete on market size or government subsidies but we can become the best place to design, test and bring products to market.

Regulatory innovation should be a comparative advantage for the UK, as a medium-sized economy with leading innovators, highly capable regulators and a political & legislative system that can move at pace. But we have not capitalised on this potential. For instance, the UK has seen delays in deploying certain technologies, such as autonomous vehicles, due to stringent and unclear regulatory requirements, allowing other countries to take the lead in these areas. In some sectors, like medicines and fintech, a backlog of regulatory approvals has dampened innovation.

The new government is right to focus on regulatory innovation as part of its industrial strategy. It is an indispensable step towards improving the UK’s competitiveness.

Today, across nearly every sector, regulators are struggling with one or more of the following issues:

- Resource (e.g. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, Food Standards Agency): Many regulators are now creaking under the weight of both increased responsibilities post Brexit (without commensurate funding increases), as well as the steeper learning curve presented by the very frontier, emerging technologies that could enable breakthrough social and economic progress.

- Rules (e.g. Office for Nuclear Regulation, Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority): Other regulators are constrained by the rules they operate within, waiting on investment of scarce ministerial and parliamentary time to update archaic rulebooks for the modern day or to design entirely new frameworks for novel issues.

- Risk appetite (e.g. Financial Conduct Authority, Civil Aviation Authority): These regulators lack the appetite, ambition, culture and incentive to take risk, frequently relegating their ‘competitiveness’ and/or ‘growth’ objective as secondary to that of consumer protection – delaying and denying innovation becomes the path of least resistance, in order to ‘protect consumers’. But this binary, trade-off framing is flawed: short-term conservatism ultimately leaves consumers worse off, curtailing the competition and innovation required to unseat inefficient, legacy incumbents.

More detail about these constraints is set out in Form Ventures’ Fix The Regulators report (co-authored by Andrew Bennett and Leo Ringer).

Previous governments have focused too much on distracting ‘red tape challenges’ or ‘one in, one out’ deregulatory mantras. Instead, the opportunity for the Regulatory Innovation Office is to build durable state capacity for regulatory innovation: understanding the frontier of technology, identifying the appropriate structural reforms to enable them, and playing the funding, coordinating, and accountability role required to deliver them as quickly as possible.

But the government must ensure the RIO is set up appropriately to achieve its potential. There are 3 scenarios for this:

- Risk of failure: Where a basic new DSIT unit is established, but with minimal political or financial backing so its influence quickly wanes

- Capability stepchange: Empowered, internal DSIT Directorate modelled on AISI or Vaccines Taskforce, with political backing, £100m up-front commitment and external expertise.

- Enduring legacy: Spin out the fully-resourced Directorate as a new, statutory authority, acting as a new, ‘regulator of last resort’ & pioneering a new model of ‘innovation concurrency’

Although current details are scant, merging the Regulatory Horizons Council and Regulator Pioneers Fund into a single, basic new DSIT unit must only be a temporary, initial step. Success requires a more ambitious approach.

Plan of Action

Setting up the RIO correctly

The government must ensure the RIO is established with the appropriate structure and scope to achieve its potential. These issues are related: the government has already decided that the RIO will, at least initially, be part of DSIT, while DBT will retain broader responsibility for regulator performance management. Although there are good reasons for DBT retaining this portfolio, there is a risk that the RIO could be easily ignored by other departments without its own, additional levers: most regulators are not directly sponsored by DSIT. At minimum, the RIO should retain a close relationship with both No10 and HMT in order for it to successfully play its cross-government role.

With DBT implicitly retaining responsibility for wider regulatory performance, there are 2 remaining ‘jobs to be done’ for the RIO. It is critical it covers both:

- Unlocking new sectors by enabling frontier, disruptive innovation and emerging technologies. A key function of the RIO will be looking at technologies that do not fit neatly into the existing landscape of economic regulation. This could be technologies that are covered by several sector regulators, or technologies that are not covered by an existing sectoral regulator. In this way, the RIO will pick up existing work that DSIT and the Regulatory Horizons Council have been leading on emerging technologies like space, quantum and robotics.

- Upgrading existing sectors by accelerating innovation in mature regulated markets where barriers to innovation have grown. There is currently a gap between DBT’s work on economic regulation in general and DSIT’s work on regulatory innovation for frontier technologies. The work of enabling existing innovation in mature regulated markets is too often falling through the cracks. Therefore, in addition to its work on those frontier technologies, the RIO should have a role in enabling innovation in mature regulated markets. This is where the greatest short-term benefits could accrue, for example working with the MHRA and CQC on quicker approvals, both for medicines and software-based medical devices or clinical services; the FCA to clear fintech authorisation backlogs; or with the Office for Nuclear Regulation on more proportionate regulation of new reactor designs.

It is critical to distinguish between these responsibilities because DSIT is already well set up to do the first – given its Emerging Technologies and Regulatory Innovation directorate – but needs to build capability and wield new powers in order to succeed at the latter. If the DSIT-DBT split means that separate bodies are responsible for ‘enabling innovation’ and ‘holding regulators to account’, then there is a risk that opportunities in this middle category – accelerating ready-to-go technologies in existing regulated sectors – will be missed. It is essential this does not happen, particularly because this is where most of this parliament’s productivity gains and growth opportunities – and therefore political dividends! – will come from.

Proving the model

The RIO cannot fix all regulatory issues on day one, but also needs to take early decisions to get going quickly. Therefore it’s encouraging that it’s been launched with 4 priority sectors: engineering biology, space, AI in healthcare, and connected and autonomous technologies (e.g. drones).

However, in order to use this initial phase to genuinely prove the model, we propose a 3-step approach:

- Clarify criteria: The initial priority areas are strong choices, but there are other candidates – both for near-term impact (e.g. nuclear) and long-term potential (e.g. neural interfaces, climate cooling) that have not been included. In time the RIO should build a portfolio of focus areas that reflect a range of payoff periods and impact potential, chosen according to:

- clear, near-term impact and urgent market need

- breakthrough potential for the Missions, and

- longer-term, more speculative technologies

- Narrow down: ‘AI in healthcare’ is a hugely promising area, but also an enormously wide category in terms of regulatory barriers, covering everything from AI medical device approval timelines to fledgling authorisation pathways for personalised medicines (where mass clinical trials don’t apply). During this initial phase, greater specificity about which regulatory issues the RIO is intended to address would be helpful. Given the pressures on GP appointments, fully-automated diagnostic services would be a strong candidate for a more specific focus.

- Run hard: It’s critical that the RIO is empowered by No10 and HMT to run hard at these exemplars to make a difference, rather than previously intractable issues merely now having a new home. This initial phase should be about setting the right tone and urgency, to signal how it wants to work and the level of ambition it wants to encourage. Then, in time, the RIO could add to this portfolio to scale its impact further, particularly if it becomes a more independent body with political and financial backing, akin to ARIA or AISI.

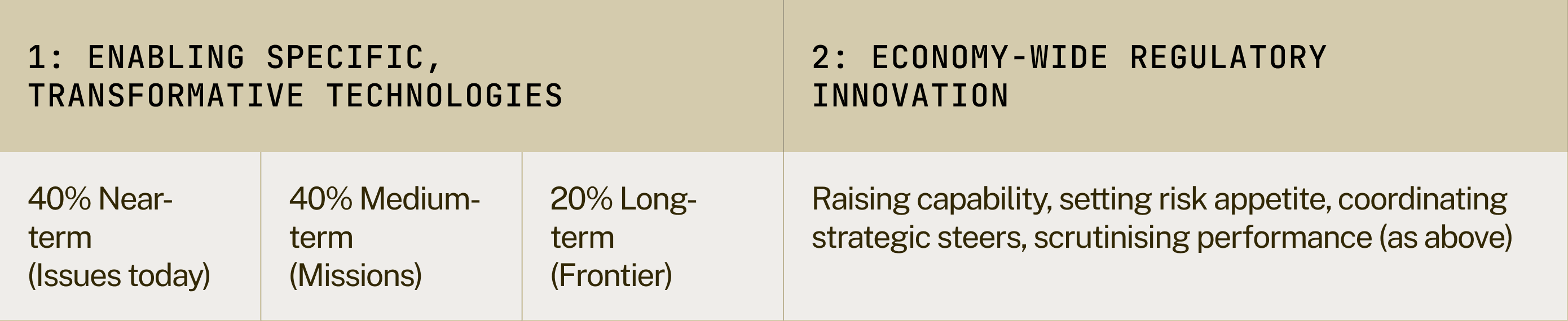

We suggest the RIO divides its time between these objectives, allowing it to demonstrate short-term progress while also working on long-term opportunities. The 40/40/20 split is a suggestion:

Empower the RIO

- Appoint an external Chair who understands both regulators and innovators. The most successful bodies working within science and technology within departments, such as the Vaccines Taskforce and AI Safety Institute, have been led by externally-appointed leaders. Enabling success in science & technology typically involves placing bets that may or may not pay off. In this instance, it could mean the RIO enabling regulatory innovation in a certain market that fails to become a commercial success for the UK. This is not easy for Whitehall. The leadership of an external, expert Chair can bring a healthy challenge, and encourage different ways of policy-making and delivery. The RIO sits at the intersection of two ecosystems: the regulatory community and the technology community. The Chair should be comfortable operating in both worlds.

- Create a £100m Regulatory Innovation Fund, which the RIO controls. Previous initiatives like the Regulatory Pioneers Fund have not had the scale to have a meaningful impact. Given that regulatory innovation is an essential industrial strategy intervention, if the Treasury cannot find funding for this, it must ask itself where it expects growth to come from. The allocation of the Fund should be controlled by the RIO, not the Treasury. Spending teams in the Treasury would face a constant incentive to divert such funding away from innovative activities, which have an uncertain, long-term payoff, towards plugging immediate funding gaps for regulators. Furthermore, having control of some funding is a key tool to ensuring the RIO has its own credibility. In the absence of this, regulators have weaker incentives to engage with it in good faith. Practically, the fund should be used for both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ projects: i.e where the RIO has identified opportunities, it should be able to fund regulatory innovation work to deliver them directly. But it should also be responsive to bids from regulators, akin to the current Regulator Pioneers Fund model.

- Involve the Treasury and No. 10. Through the RIO, DSIT needs to play the role of a ‘central’ department: influencing other departments and the regulators they sponsor. This is why we recommend the RIO has control of a Regulatory Innovation Fund but the fund cannot address situations where the problem is not related to funding, such as insufficient risk appetite. We also recommend scoping work on the potential for statutory powers in the long-term but this process would take time (e.g. the process to set up ARIA took 2 years from Queen’s Speech to Royal Assent). For now, the RIO should be empowered to work on a more informal basis with departments and regulators, by making clear that it has the backing of the PM and Chancellor, as a key part of the government’s industrial strategy.

Alongside these starting points, the RIO also needs a wider set of levers to carry out its activities – particularly to drive behaviour change across regulators and departments. It should:

- Monitor regulator performance. The RIO should monitor, benchmark and scrutinise regulators’ support of innovation by creating and maintaining datasets about performance, budgets and outcomes (e.g. approval timelines for new products and services). It should work with the NAO and ONS to build comparable KPIs across regulators and build estimates for the economic costs of delayed and foregone innovation.

- Publish an annual State of Regulatory Innovation report, starting with the Regulation chapter of the Industrial Strategy: The RIO should contribute a report on the regulatory innovation landscape which becomes the regulation ‘chapter’ of the government’s industrial strategy, written together with DBT and HM Treasury. It would translate industrial strategy priorities, and the data on current regulatory performance to provide steers for regulators. It would highlight the most important areas where there is growth potential but innovation is being stifled. This should then be updated annually, to track progress and spotlight the best-performing and worst-offending regulators.

- Reports on particular sectors or technologies. The RIO should write a report for each priority sector/technology. Where the RIO is focused on mature markets, its reports may look akin to light-touch CMA-style ‘market studies’, to diagnose where regulation is acting against innovation. These reports should contain recommendations to government and regulators, with a requirement for the government to respond within one month.

- Provide surge capacity for regulatory innovation. Where it has identified a problem, the RIO should be empowered to directly solve it where it is able. Whereas the Regulatory Horizons Council stopped at writing reports, the RIO should tackle the ‘last mile’ of policy delivery, not only making recommendations but also executing them itself. For example, where businesses must seek approval from multiple sectoral regulators, the RIO could help coordinate complex applications, learning from examples such as Accelerate Estonia to do the heavy lifting on behalf of multiple regulators. It could also scope out how to deliver novel mechanisms like ‘pay for speed’ options or international recognition procedures, where regulators have not had capacity to accelerate this work.

- Coordinate regulatory and legislative changes to ensure timely delivery: Finally, as well as monitoring regulators’ own efforts to enable innovation, the RIO should also surface, triage and prioritise requests for legislative changes or Ministerial steers from regulators, while requiring departments to explain why pro-innovation changes have not been taken forward.

Scope the RIO on statutory footing

Finally, during the initial period where the RIO is focused on 3-5 exemplar sectors and building up how it will work with regulators, the Chair should also run a special project to explore whether statutory powers are needed, which may be needed in the long run for the RIO to have real impact and compel change from regulators.

In practice, this could work by the RIO having powers to step in as a “regulator of last resort”, “regulatory clearing house”, or “n+1 regulator”. In effect, this version of the organisation would have the power to grant temporary licences for new technologies in existing sectors, overriding the sectoral regulator – i.e. to pioneer a new form of ‘innovation concurrency’ akin to the CMA’s competition concurrency agreements with sectoral regulators. It could play a particularly important role in the regulation of new technologies that do not fit neatly within a single sector, where messy or overlapping responsibilities delay delivery – some companies have needed to seek approval from up to 11 different regulators.

We believe there is real potential in this on its own merits. Initiating this work immediately would also signal the government’s intent to shake up the system and to tackle the inertia amongst departments and regulators that has set in.

FAQs

How should the RIO measure (its own) success?

Early on, the RIO should measure its success by unblocking innovations that have been stuck in regulatory limbo while other countries have made progress, such as cell-cultivated foods or cheaper nuclear designs that do not sacrifice safety. These technologies cannot get to market without regulatory approval, so the RIO’s intervention is critical to avoid the UK falling even further behind.

In time, a successful RIO should also make the UK a leader in newer industries such as BVLOS drones or neural interfaces, flipping the dynamic so that these technologies can get to market quicker than anywhere else in the world.

Finally, by building datasets on regulatory performance and budgets, the RIO would be able to compile annual indicators not only to hold regulator’s accountable but also to monitor its own impact.

What level of financial resourcing is needed?

Relative to the c. £15bn spent annually by government on R&D, the budget for regulators to help get these innovations to market is minimal. The £100m Regulatory Innovation Fund could be allocated entirely within DSIT’s wider budget, and at this level it would have the scale that previous initiatives have lacked. E.g. When the MHRA got £10m to clear the clinical trials backlog, it did so successfully but only by relegating other work in the process. Similarly, the £10m DSIT fund for AI regulatory capability and the £12m Regulator Pioneers Fund – both of which are then divided up between multiple regulators – are too sub-scale to touch the sides of the problem.

Alongside this, in order for this £100m to genuinely be focused on regulatory innovation, wider funding uplifts are also required to avoid this fund being misused by cash-strapped regulators for business-as-usual activity. E.g. Although the Food Standards Agency has now been given £1.6m by DSIT to work on cultivated food, this is against a wider £30-40m real-terms cut given its budget has been frozen for 3 years until 2025.

How much would these reforms help growth, and over what timeframe?

The design of regulation can have a significant impact on innovation and growth, though the overall impact is difficult to measure. Some economists have estimated the impact of specific regulations on growth. For example, Aghion et al (2023) find that the design of one particular set of regulations in France lowered aggregate innovation, and therefore growth, by 5.4%.

This research can give a sense of the potential impacts of regulatory reform on growth, but assessing the ex ante impact of the RIO is difficult. In addition to those difficulties, by necessity, the RIO will ‘place bets’ on certain technologies. The extent to which these bets ‘pay off’ and result in commercial success in the UK is uncertain by its nature.

Nevertheless, we know that frontier technology startups that can’t rely on getting to market in the UK, routinely consider moving to markets like the US, Singapore or France. This agenda is a critical enabler for UK competitiveness and the ability of companies to scale up.

How is the RIO different from the Regulatory Horizons Council?

The Regulatory Horizons Council conducted valuable work, but regrettably it has been too easy for departments to ignore. Creating an empowered Regulatory Innovation Office, with the leadership, funding and political backing this entails, would help it reach its promise in a way the Regulatory Horizons Council was unable to. The RIO should also look at areas that weren’t covered by the Regulatory Horizons Council, such as enabling innovation in mature regulated sectors.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]