Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. The Challenge & Opportunity

- 3. The Plan of Action

- 4. FAQs

- 5. Appendix: Economic Model

- 6. Authors

Summary

- The development and adoption of AI presents a monumental potential for economic growth, increased productivity, and shared prosperity. The UK should be ambitious. The government should clear barriers faced by firms seeking to train, deploy and develop models in the UK, including foundation models. This would support AI companies investing in the UK, allow British companies building AI products to compete abroad, and contribute to making the UK the “best place to start and scale an AI business”.

- Delivering on this ambition will require the government to make difficult decisions, including investing in energy infrastructure, supporting top talent, and giving firms access to datasets to develop products. Government has access to one cost-free intervention that would supercharge domestic AI capabilities: liberalise the text and data mining (TDM) copyright regime. There is currently a live IPO consultation on the topic but its framing suggests an approach that would unduly limit AI development in the UK. An opt-out model would result in a loss of at least £29.9 billion within the next 5 years to the UK's GDP.

- In 2011, an independent government report (The Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property) determined that the UK’s restrictive data regime “block[s] valuable new technologies” and hampers economic growth. While this legal framework has been holding back UK R&D and tech for years, its impact has become even more consequential in the face of an AI revolution.

- A restrictive copyright regime in the UK does not, unfortunately, protect UK content creators from their content being used by AI companies around the world. Given other jurisdictions with more liberal regimes exist, its only practical effect is to prevent companies based in the UK from using that data and developing new technology here. Regimes like an opt-out model would be a lose-lose policy: it would hurt the UK R&D and tech industry without protecting the creative industry.

- Following the example of countries like Japan, the UK should adopt text and data mining copyright exceptions that allow developers to analyse and train on publicly available data that is already accessible or already has been lawfully acquired. This should not be misconstrued:

- A TDM exception would not affect personal data or privacy obligations under the law nor will it make it such that developers can avoid paying for lawful access to content. Companies would also still be required to license copyright content to which they do not have access.

The Challenge & Opportunity

The Prime Minister is right to set out an ambition to make the UK an “AI superpower”. As a general-purpose technology, AI will likely transform the economic and social fabric of the world. General-purpose technologies affect entire economic systems – examples include the steam engine, electricity, and information technology. History shows that a society’s ability to build and harness these technologies define whether they will benefit from it. The next GPT revolution is already happening: if we stand still we will decline.

The government has made growth its top priority, and delivering on that commitment means bold policy choices. The best leaders understand that difficult decisions, even those that face initial resistance, are necessary to secure long-term prosperity. Copyright and AI has been a politically sensitive issue, but the economic and strategic case for a flexible regime is undeniable. If the UK is serious about leading the world in AI and attracting global investment, it must act decisively. Introducing a text and data mining exception in copyright law would send a strong signal that the UK is open for innovation, boosting immediate AI investment and sustained economic growth.

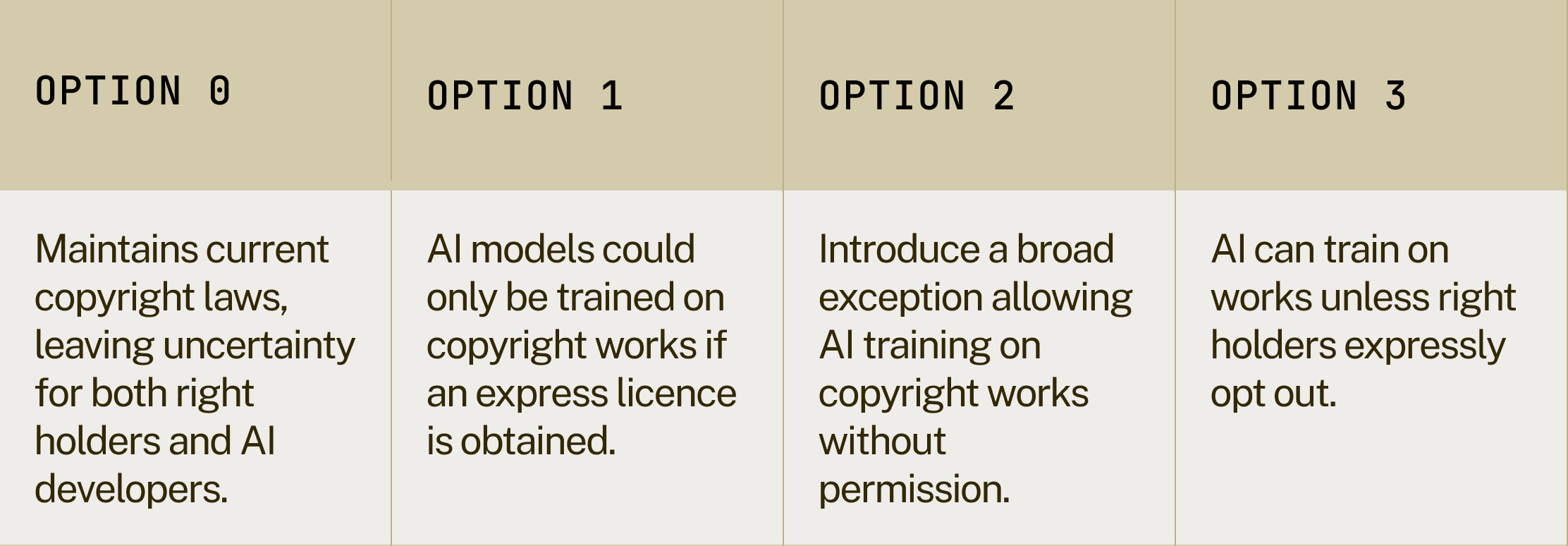

The current copyright and AI consultation outlines four options that the government is considering (table 1). This briefing argues that the proposed government approach of option 3 fails at meeting the objectives of control, access, and transparency set out by the consultation. Instead, it puts forward an argument for option 2, explaining why it would yield the best economic and strategic dividends. It then suggests how this could be implemented.

Table 1: An overview of the policy options being considered in the copyright and AI consultation

Access to data (and lots of it) is fundamental to building AI models

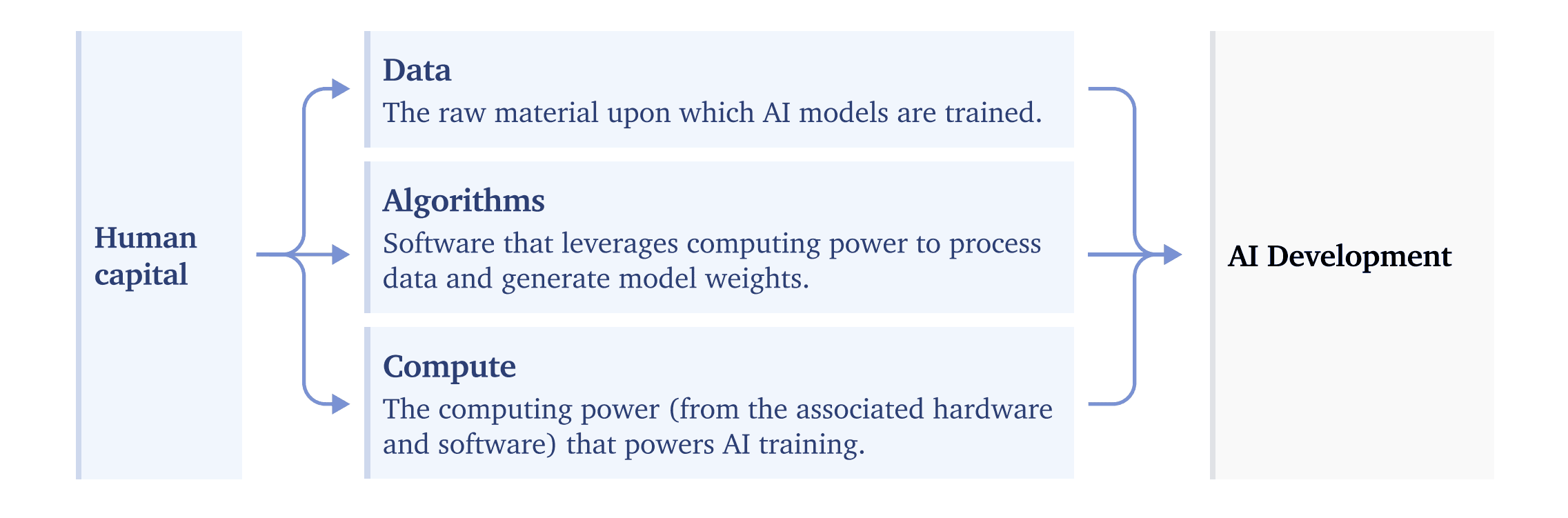

To put it very simply, AI is built on three ‘ingredients’: computing power, data, and algorithms to process that data and train models. The result is a model that can recognise patterns, make predictions, and generate insights (figure 1).

Figure 1: The Three Technical Inputs to AI – Data, Algorithms, and Compute

Source: Computing Power and the Governance of Artificial Intelligence

Foundational AI models like ChatGPT or Claude are trained on publicly accessible data on the web. These models are trained on hundreds of terabytes to petabytes of text, images, audio, and video data. They do not only need lots of data – they need lots of high quality data. A good rule of thumb is: all things held constant, the more high quality data a model is trained on, the better it will be.

AI models themselves do not store data like a database; they do not retain full texts, images, or multimedia. Instead, models convert a wide array of data into statistical representations of patterns, structures, and styles. When prompted, these vectors act like an abstract map, so instead of retrieving data they synthesise this learning to create something new.

Policy decisions mean British AI models are not being developed

Data is one of the three fundamental inputs to developing AI models, and placing restrictions on its use in the UK kneecaps the UK’s ability to contribute to the development of the technology domestically and capture many of its benefits. Companies are still free to develop the technology in other jurisdictions without any constraints, which represents a pure loss to the UK. While the law on training AI models is relatively clear—model developers cannot train on publicly available data in the UK—legal uncertainty lies in how AI systems are used. Deployers face ambiguity about their liability if an underlying model infringes copyright or other regulations. This ongoing uncertainty creates a constant threat of lawsuits, which chills investment, restricts tech adoption, and slows down innovation.

However, the opt-out model that has been proposed, which is similar to what has been adopted in the EU (option 3), introduces its own set of problems. It would make developing AI models in the UK more expensive than in other jurisdictions. Companies—regardless of size—could choose to simply develop the technology in jurisdictions without such constraints. This would incentivise firms currently based in the UK to relocate and would effectively bar those based in the UK from competing on an equal footing with foreign firms. Meanwhile, large incumbents would have no issue training their models in more permissive jurisdictions and reaping the rewards.

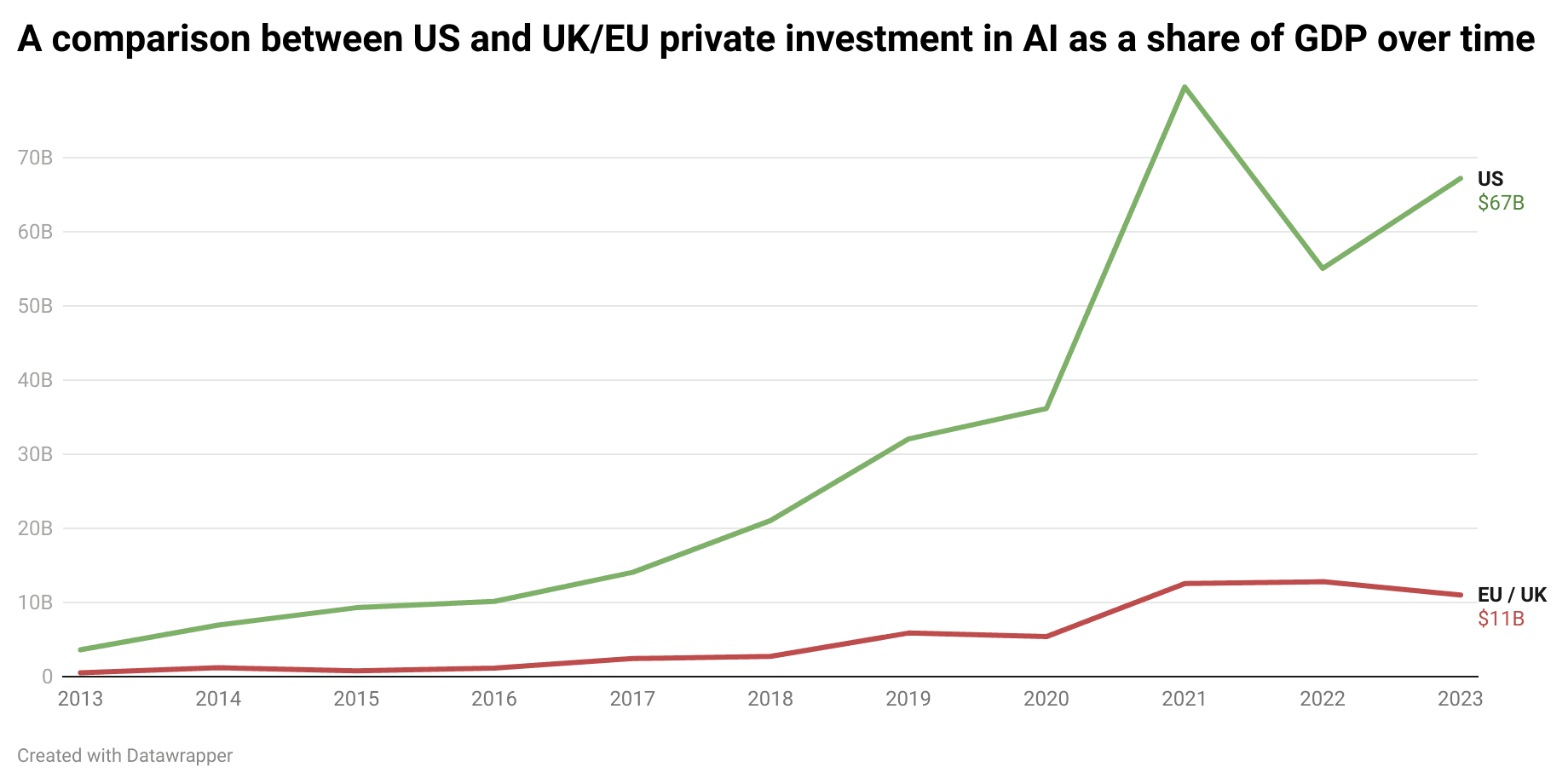

Beyond cost, enforcement would be nearly impossible. Although there are some standards being explored, in practice there is no effective, at-scale solution beyond imposing restrictive database monitoring rules. Anyone with moderate compute power could train open-source models on unauthorised data, and authorities would have no practical way of detecting infringement. The result would be a system that penalises law-abiding UK-based companies while doing little to prevent AI development elsewhere. The UK would find itself unable to attract AI investment or talent, losing high-quality jobs and reinforcing the growing gap in AI private investment between the US and the UK & EU (figure 2).

Figure 2: The US has far outpaced the UK and EU in private investment in AI as a share of GDP over time

Businesses in the UK (and the EU) cannot be expected to compete with AI companies in places like the US, Japan, and China if they are forced to operate with the brakes on. We’ve already seen the dampening effect of the copyright regime on innovation in the UK. Stability AI, one of the few British based AI companies, does not train its models in the UK and has established offices in the US and Japan in part due to the more favourable copyright regimes there.

Table 2: Comparing Copyright and AI Training Laws in China, US, EU, and UK

Options 1 and 3 do not protect the creative industry

From the perspective of a creator, even if your content is protected under UK or EU law, a company from another jurisdiction like the US is not bound by UK or EU copyright rules. This means that having a restrictive copyright regime in the UK would not protect UK content creators from their content being scraped by companies in countries with more liberal copyright rules like the US and China.

The EU, for example, cannot determine how models are trained in other jurisdictions. If copyrighted content is used in training outside the EU, the EU AI Act cannot prevent or retroactively control that training process. This is consistent with how most international law works—jurisdictions cannot generally impose extraterritorial restrictions unless special agreements exist. This means that AI models developed and deployed in another country can still use copyrighted material that is publicly available in its training. EU-based rights holders that choose to opt out would still have their data used in training runs that occur in, for example, the US or China. This is not merely a hypothetical – it is literally how models like GPT-4o have been trained.

The EU AI Act does require models trained, developed and deployed in the EU to comply with local regulatory restrictions, but in practice this is unlikely to be sustainable. Recital 106 AI Act states that providers must comply with the opt-out model even if training takes place outside the EU, for instance in a jurisdiction with laxer requirements. The rationale is that this would “ensure a level playing field”, where providers don’t “gain a competitive advantage in the Union market by applying lower copyright standards than those provided in the Union.”

This may superficially seem like a good thing – for a long time the EU has tried to flex the weight of its market to dictate global regulatory practices. But there are three reasons to think this position is unsustainable.

First, AI models are less dependent on access to any single market than industries like pharmaceuticals or automotive, where market-specific regulations have traditionally influenced global standards. Major AI developers can deploy their products in regions with more flexible rules, capturing large user bases outside the EU, and remain highly profitable without immediate EU access (table 4).

Second, enforcing compliance with EU standards for models trained outside its jurisdiction presents significant technical and legal challenges. Proving that a model unlawfully incorporated opt-out data during training is difficult due to the lack of transparency in AI training pipelines and the scale of datasets used. This creates an enforcement gap, where non-compliant models can still be used in the EU through informal or indirect means.

Finally, the companies developing frontier AI are unlikely to pause or slow their progress due to regulatory hurdles in any single market, even one as large as the EU. The pursuit of AGI is a global, high-stakes race driven by the promise of transformative capabilities, significant returns on investment, and strategic geopolitical advantages. Companies will continue training models and pushing boundaries in jurisdictions with more permissive rules. AGI development is too valuable and competitive to be dictated solely by EU restrictions.

Thus, it is likely that custom EU-specific models with lower capabilities would be developed for the market, while the race for AGI continues elsewhere. We will also continue to see models deployed later in the UK and EU, so foreign businesses and consumers will have access to the most advanced models, whereas UK and EU users will have to wait until models have cleared regulatory hurdles, or after pre-deployment fine tuning has taken place.

Table 3: Stringent regulatory demands are already leading to model release delays in the UK and EU

Rather than shaping global norms, the EU risks isolating itself and slowing domestic innovation while competitors in jurisdictions with more permissive regimes accelerate ahead. This is already happening. OpenAI models like Sora and Deep Research are all currently unavailable in the EU and UK (table 2), meaning companies in the EU and UK are not only missing out on the productivity gains from AI adoption, but also the compounding gains of building on systems that improve over time including a powerful multiplier of wider economic growth. This significant productivity hit occurs all the while failing in the primary aim of the legislation: protecting rights holders and content creators, as publicly available data produced by creative industries will be used by foreign companies in any case. The UK should not follow the EU down this path.

Table 4: Possible Copyright and AI Regulation Scenarios in the UK – Policy Decisions and Their Most Likely Outcomes

Table 5: Option 3 fails on all objectives set out by government

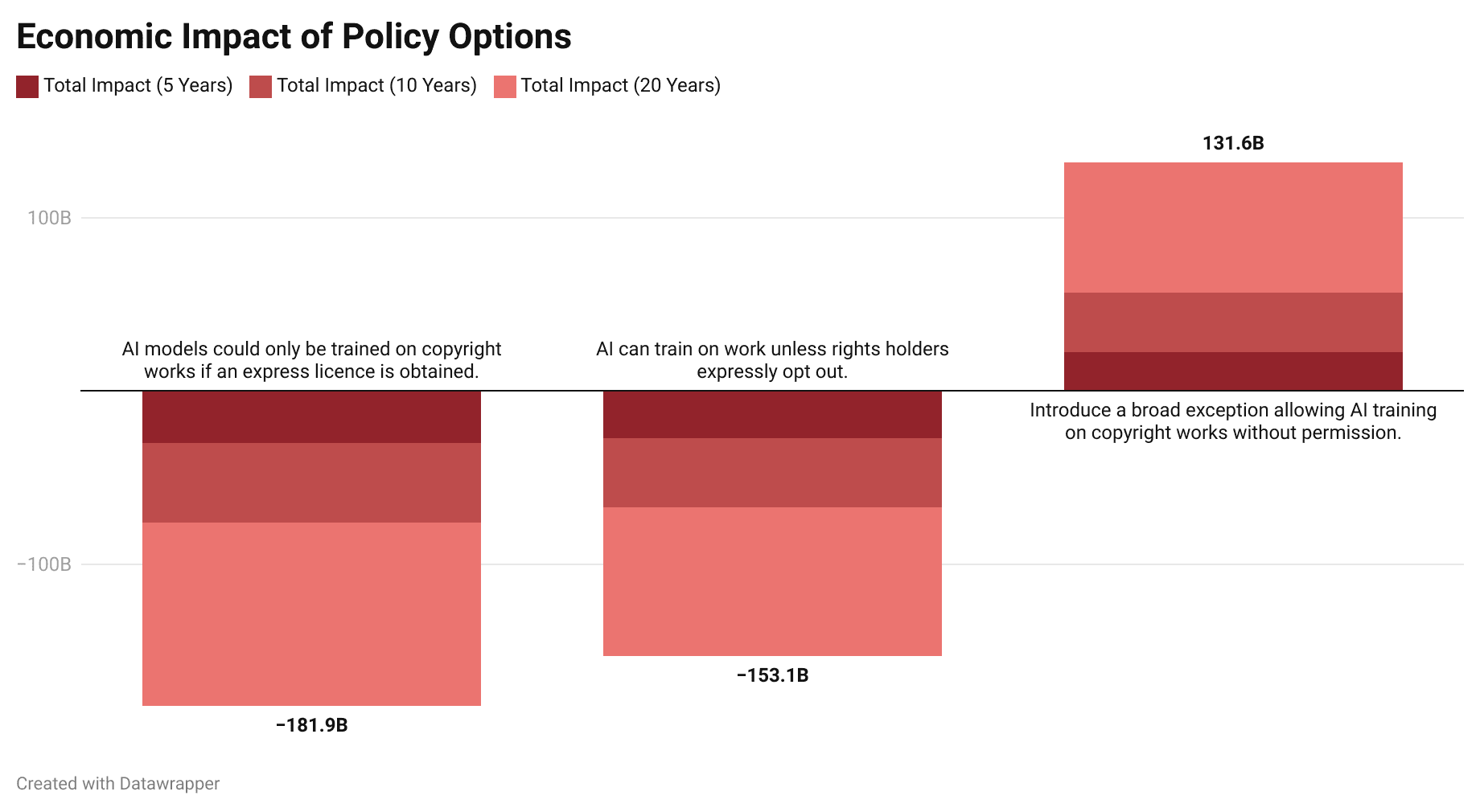

An opt-out model would not only impact those building foundational models but also affect British startups and firms building applications on top of these models. For example, their products would need a wide availability of data to fine-tune models or create reinforcement learning pipelines. In other words, an opt-out model would negatively impact innovation across the entire AI sector, not just those building foundation models. Indeed, economic research actually suggests that copyright is not as useful for encouraging innovation as commonly thought. Furthermore, lack of access to state-of-art models would lead to economic losses from British businesses not adopting new technology. Empirical analysis shows that improved capability to access innovation and knowledge has a significant positive effect on economic growth. We predict that – in a world where the UK has an opt-out model and mandates models deployed on the UK market to comply with local copyright restrictions – the UK would suffer economic losses of at least £29.9bn within the next 5 years, £75.86bn within the next 10 years, and £181.96bn in the next 20 years (table 5).

Table 6: Economic impact of policy options considered by the AI & copyright consultation over 5, 10, and 20 years

*See appendix for more information on the economic model

Figure 3: Economic impact of policy options considered by the AI & copyright consultation over 5, 10, and 20 years

There are better ways to support the creative industry

Our creative industry is adaptive and flexible. It has survived shifts in the market and cleverly found new ways to monetise as technology has shifted from vinyl to iPods, reruns to streaming, box office sales to digital releases. The emergence of AI technology and the potential it has for revolutionising all areas of our lives means they will have to do so again, whether or not we adopt a restrictive copyright regime.

For example, Christie’s has now launched its first AI art auction, featuring work by the likes of Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst who are not only exploring new creative practices but also novel commercial models for both artistic works and for data licensing. Similarly, archives of private, high quality data can also be monetised for AI model training, with new data marketplaces like Human Native AI connecting content producers that want to sell private datasets to AI developers. The lesson isn’t that any one of these approaches is guaranteed to work, but that art and the surrounding economies can evolve.

There are also other, better ways to protect our creative industry than adopting a restrictive copyright regime. Arts funding has declined in recent years, but this could be reversed and funded by the proceeds of growth – or even potentially in partnership with AI labs.

Restricting this process of adoption through overprotection, however, risks suffocating innovation that drove our creative industries forward. Historically, the most successful industries have been those that embraced technological disruption and incorporated it into their creative output. For example, rather than resisting the rise of digital art or online platforms, many artists and producers have successfully integrated them to broaden their reach and revenue streams. Preventing the development of cutting-edge technology in the UK would not provide the creative industries with the tools required to face the upcoming transformation of all industries, but it will ensure the UK economy will be in a weaker position to face these challenges.

AI can actually expand the limits of what is possible in human creativity. A recent study shows that the creative industry is behind only the IT industry in rates of using AI to augment their work. A new generation of artists are actively using AI as a tool in their work. Including independent musicians, 60% of whom are already using AI to make music.

Technological changes have, in the past, changed the economic reality of the creative sectors. The camera, for example, systematically devalued painting and portraiture but we did not see (as some feared) the decimation of human creativity. Artists adapted and gave us the wonders of Impressionism and Surrealist photography, and today painting is still the lion's share of the fine art market.

The Plan of Action

Japan is a good model of a country that, since 2009, have had exceptions to copyright law for data analysis and machine learning (Art 30-4 of the Japanese Copyright Act). This does not mean that tech companies are able to reproduce creators’ content without consequences – Japan is highly respectful of intellectual property and values both its research-intensive sectors of the economy and its large creative sector (popular Japanese cultural exports include manga, anime, literature, J-pop, etc.). Furthermore, in an interesting lesson for the UK, Japan sees IP as so strategically important for the country’s economy: it has established an “Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters” comprising all members of the Cabinet, chaired by the Japanese Prime Minister.

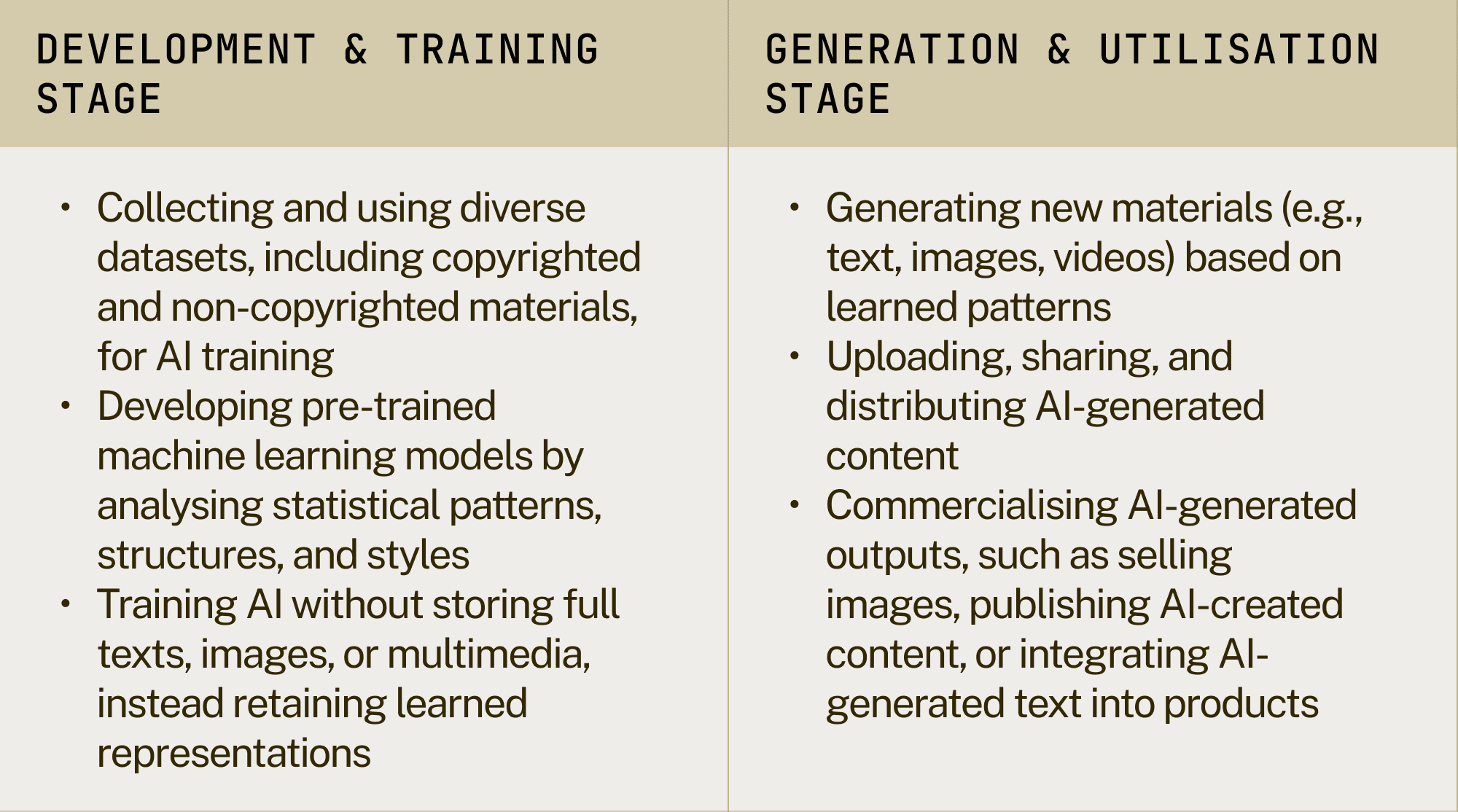

The Japanese government recently published updated guidance that outlines how the law should be interpreted in light of recent developments in AI. The guidance clarifies that AI companies in Japan are able to analyse publicly accessible data to train their models. In common with other countries, nevertheless, Japan applies the same copyright infringement standards to AI-generated outputs as it does to traditional, human-generated content. The Japanese system differentiates between the use of copyrighted works in the “development & training stage” and infringement in the “generation & utilisation stage”.

Table 7: Distinguishing AI Training from AI-Generated Content

As is the case in the UK, if an AI-generated image or text closely resembles a copyrighted work and exhibits both substantial similarity (creative expression) and dependence (clear derivation from the original work), it constitutes infringement unless a specific exception applies. Conversely, if AI-generated content does not share substantial similarity or dependence on a specific copyrighted work, it is not considered an infringement. This holds regardless of the training process.

This aligns with existing copyright principles: an artist or journalist may be influenced by past works, but they are only infringing if they directly reproduce protected material in their own work or in cases that would unreasonably prejudice the interests of the copyright holder. By focusing on output-based infringement rather than training data restrictions, a TDM exception provides greater legal clarity while avoiding unnecessary barriers to AI innovation. Crucially, the Japanese TDM exception applies for commercial use and non-commercial research (and this is similar latitude given in the American, Singaporean, South Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, and Israeli systems).

The Japanese system also prevents copyright infringement by restricting AI training in cases of:

- Fine-tuning and Overfitting: AI developers cannot collect and use copyrighted works for fine-tuning models in a way that generates materials highly similar to the original copyrighted works. The system must create genuinely new content rather than repeating or closely mirroring specific existing works.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): AI models cannot use copyrighted works as direct input for retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems where the ultimate purpose is to replicate or significantly rely on the creative expression of the original work.

Additionally, under Japan’s Copyright Act, permission is not required for personal use cases (e.g., creating AI-generated images for private viewing) and uses that fall within established copyright exceptions. Importantly, Japanese law also permits circumvention of technical protection measures for commercial and non-commercial research purposes where the legitimate interests of the rights holders are not harmed. Furthermore, override of contracts for the purposes of machine learning is also lawful.

Given the rapid advancement of AI and the need for a clear yet flexible copyright framework, the UK should implement a similar exception for text and data mining while maintaining:

- A clear test for copyright infringement of AI-generated content, ensuring outputs are original and not just slightly altered versions of existing copyrighted material.

- Strong safeguards to prevent AI models from reproducing copyrighted content too closely, ensuring they generate genuinely new material rather than simply regurgitating existing works.

The simplest route would be to amend Section 29A CDPA 1988 (which currently allows TDM for non-commercial research) to extend it to commercial use. This could be done via a Statutory Instrument (SI) under the affirmative resolution procedure, which means it must be approved by Parliament but does not require a full Act.

A new version of Section 29A could read:

29A Copies for text and data analysis for non-commercial research

- The making of a copy of a work by a person who has lawful access to the work does not infringe copyright in the work provided that—

- the copy is made in order that a person who has lawful access to the work may:

- carry out a computational analysis, including text and data mining, of anything recorded in the work; or

- carry out the pre-training or training of a general-purpose AI model using anything recorded in the work.

- the copy is accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement (unless this would not reasonably be possible for reasons of practicality or otherwise).

- Where a copy of a work has been made by any person (A) under this section, copyright in the work is infringed if—

- the copy is transferred to any other person (B), except where:

- the transfer is authorised by the copyright owner, or

- the purpose of the transfer is to enable B to use the copy for one or more of the purposes mentioned at subsection (1)(a)

- the copy is used for any purpose other than that mentioned in subsection (1)(a), except where the use is authorised by the copyright owner.

- If a copy made under this section is subsequently dealt with—

- it is to be treated as an infringing copy for the purposes of that dealing, and

- if that dealing infringes copyright, it is to be treated as an infringing copy for all subsequent purposes.

- In subsection (3) “dealt with” means sold or let for hire, or offered or exposed for sale or hire.

- To the extent that a term of a contract purports to prevent or restrict the making of a copy which, by virtue of this section, would not infringe copyright, that term is unenforceable.

If the UK government does not as part of this consultation choose to revoke the sui generis database regime, the above changes must also be reflected in the appropriate sui generis database provisions in the Act.

This model would provide a balanced approach, ensuring that AI developers have the flexibility to train models while protecting the rights of content creators. By clearly distinguishing between lawful text and data mining and unauthorised reproduction, this framework would give rights holders strong legal recourse against companies that generate infringing content. It would also reinforce the UK’s position as a global leader in AI by reducing legal uncertainty, enabling responsible AI development, and ensuring that compliance burdens do not stifle competition or entrench the dominance of large tech firms.

FAQs

How much does the creative industries sector contribute to the UK economy?

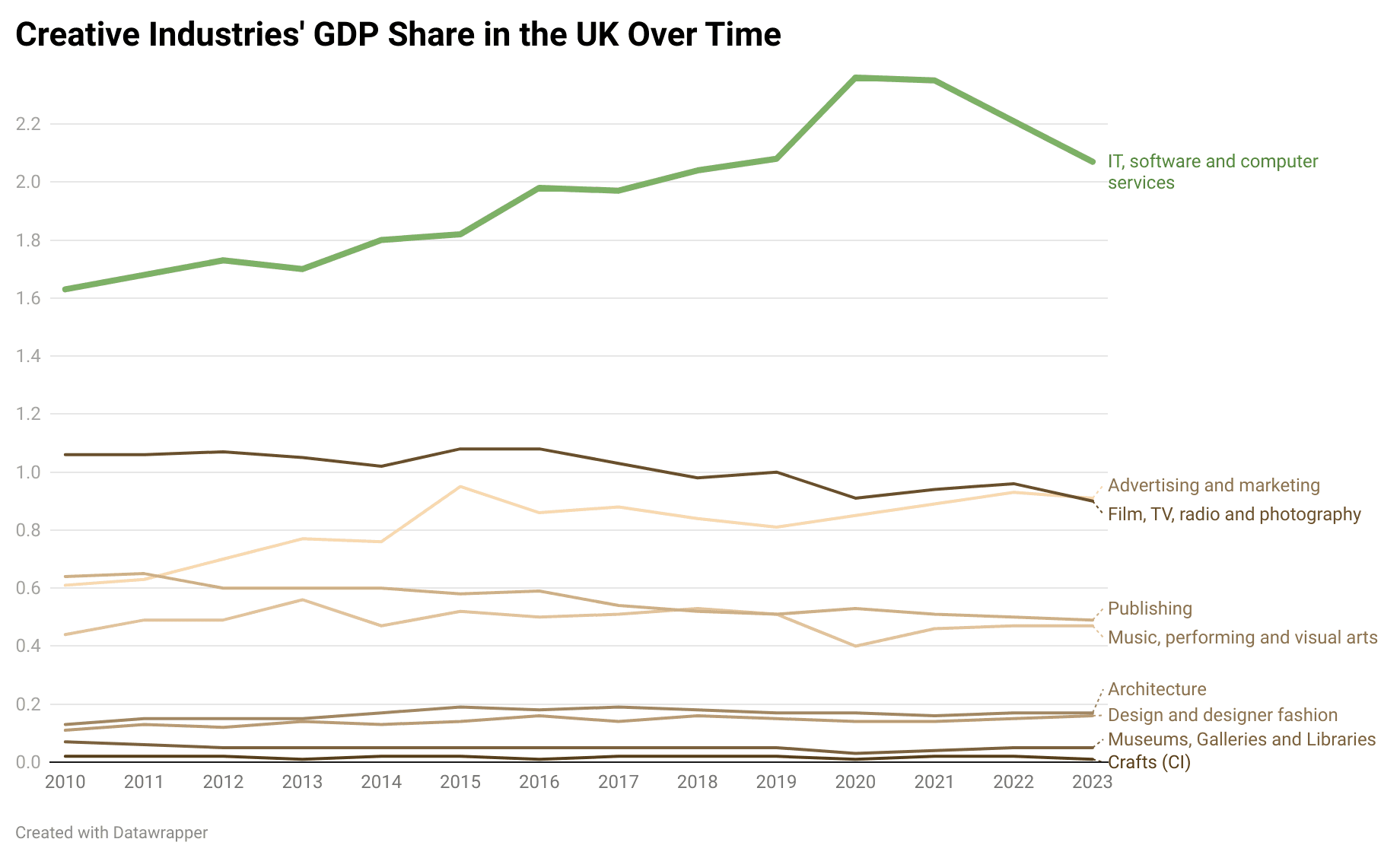

The UK’s creative industries contributed £124 billion in Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2022, accounting for 5.23% of total UK GVA. The IT, Software and Computer Services industry alone generated £53.4 billion, making up 40% of the sector’s total GVA. When combined with Advertising & Marketing, these two areas account for 57% of the creative industries’ overall contribution. Crucially, software and advertising are the only major components that have experienced sustained growth since 2010, while many other sub-sectors have stagnated or declined (figure 3).

Figure 4: IT, software, and computer Services are the only components of creative industries that have grown in the last decade

Software saw a slight dip in 2023 but has since rebounded, according to ONS data tracking the broader sector. Meanwhile, advertising is closely intertwined with software, particularly through digital advertising on social media and search engines. Any disruption to software would therefore have significant ripple effects on advertising, further constraining the sector’s overall growth.

Looking ahead, AI poses both a challenge and an opportunity for the creative industries. Software is particularly vulnerable to AI-driven disruption, and advertising, which depends heavily on digital platforms, is also at risk. In this landscape, adaptation is the only viable path forward. Without meaningful innovation and integration of AI, the industries that have driven creative sector growth in the past decade may struggle to maintain their momentum.

Why would a TDM exception be easier for courts and businesses to implement than an opt-out model?

A Text and Data Mining (TDM) exception provides a clear legal framework that simplifies compliance for businesses and enforcement for courts, whereas an opt-out model introduces significant legal uncertainty, administrative burden, and operational complexity.

With a TDM exception, AI developers can confidently train models on copyrighted works without seeking individual permissions, provided they operate within defined legal boundaries. This eliminates the need to track opt-out requests, reducing compliance costs and the risk of inadvertent infringement. In contrast, an opt-out model requires AI developers to maintain and update extensive databases of opted-out works, verify that datasets remain compliant, and ensure future versions of models do not inadvertently use restricted materials. This ongoing administrative burden creates a constantly shifting legal landscape that complicates AI development.

For courts, a TDM exception makes enforcement straightforward—they only need to assess whether AI training complied with the defined exception and whether AI-generated outputs constitute infringement. An opt-out model, however, introduces complicated legal disputes, such as determining whether an opt-out was properly submitted, whether an AI developer knowingly violated it, and what penalties should apply. Furthermore, there is no universal way to verify compliance. AI companies rarely disclose what exact data they train on (because the data they train on constitutes part of their product), making it hard for rights holders to audit.

Why does a higher compliance burden hurt UK startups and drive business abroad?

A higher compliance burden imposes significant costs on UK startups and successful domestic companies, often forcing them to relocate or limiting their ability to scale. While large tech companies can absorb these costs more easily, they still face challenges and may shift operations elsewhere rather than contend with excessive UK-specific barriers.

Stringent regulations—such as opt-out models, licensing requirements, or restrictive copyright frameworks—create prohibitive costs in legal fees, administrative overhead, and technical enforcement. For UK startups and small businesses, these burdens can be insurmountable, stifling innovation and making it harder to compete. As a result, many will either fail to enter the market or move operations abroad to jurisdictions with more favourable regulatory environments.

Even large companies, despite their greater resources, may find excessive compliance costs in the UK unappealing and choose to limit their activities here. The result is a net loss for the UK’s technology ecosystem: fewer domestic success stories, less investment, and weaker global competitiveness. Rather than protecting innovation, an overly restrictive regulatory environment risks hollowing out the sector, making the UK a less attractive place to build and grow technology businesses.

How would this impact our data adequacy with the EU?

EU Data Adequacy is important for the UK economy and our relationship with the EU. Achieving Data Adequacy after Brexit was a key milestone for future EU-UK cooperation. In contrast, the US’s lack of full Data Adequacy with the EU restricts the free transfer of data between the two jurisdictions.

It is important that any changes in copyright law are designed to retain Data Adequacy with the EU. This helps ensure:

- Seamless data flows – UK-EU data can flow without extra legal barriers, reducing costs for businesses. This is particularly important for finance, tech, healthcare, and professional services reliant on real-time data.

- Research Collaboration – enabling UK firms to comply with EU regulations and participate in EU programs like Horizon Europe.

- Law enforcement & security – Data Adequacy supports intelligence-sharing with Europol and cross-border crime prevention.

- Competitiveness & Investment – Data Adequacy encourages investment and reduces legal risks for UK companies handling EU data.

We are confident that our proposal for a TDM exemption will meet EU Data Adequacy requirements. Primarily, because the exception we propose is based on Japan’s TDM exception, and Japan has had EU Data Adequacy since 2019. Japan and the EU have a close trading relationship covered by the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement. UK firms are even more closely integrated with the EU, and it is unlikely that the Commission will wish to introduce new frictions for cross-border trade.

Secondly, the UK has a strong case to argue that its data regime will remain less liberalised than that of the US. Since the TDM carve-out applies only to using data for data analysis and processing, this is much narrower than the US’s broad fair-use regime. Furthermore, even the US has a Data Adequacy Framework with the EU, even if this falls short of Full Data Adequacy. In practice this allows for a relatively free flow of data between the US and the EU.

What would a TDM exception mean for the UK’s existing international legal obligations?

Countries with TDM exceptions and flexible copyright systems (like Japan, the US, Singapore, South Korea, and Israel) are signatories to treaties mentioned in the consultation like the Berne Convention, Rome Convention, WCT, WPPT and TRIPS Agreement, proving it is possible to remain compliant with these obligations while implementing option 2.

Appendix: Economic Model

Model Structure and Design

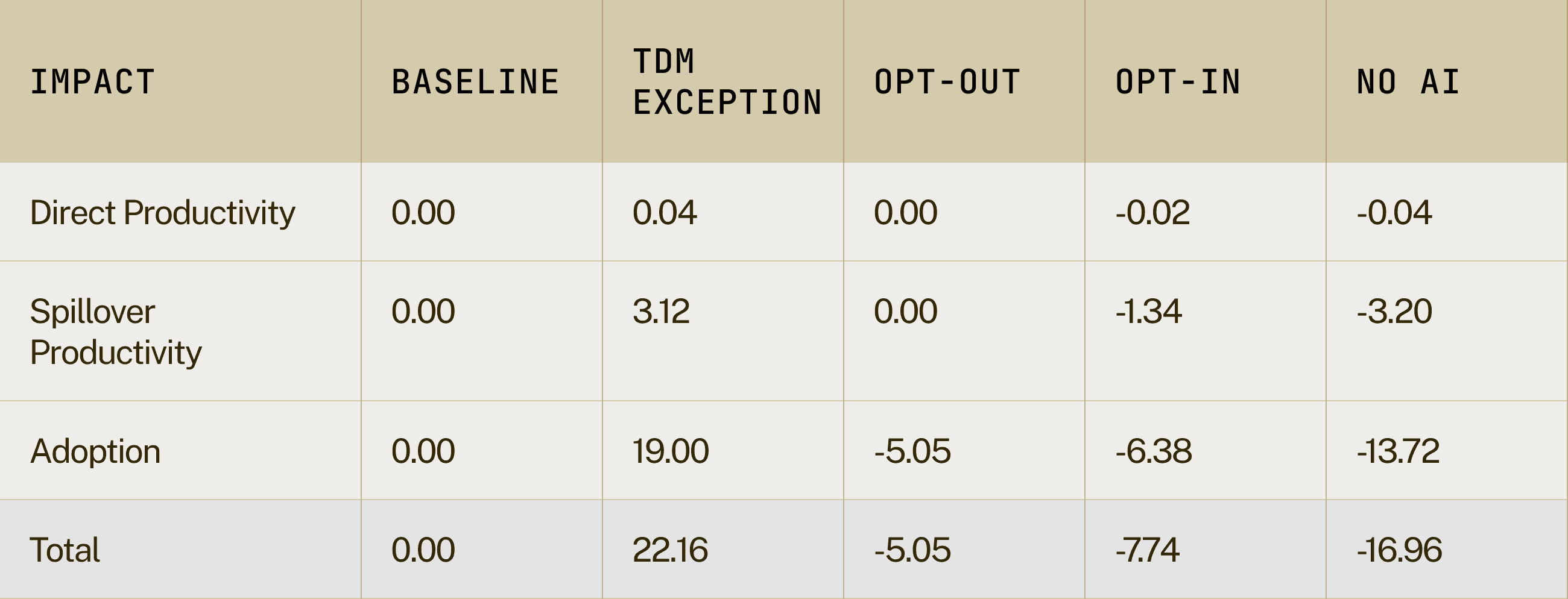

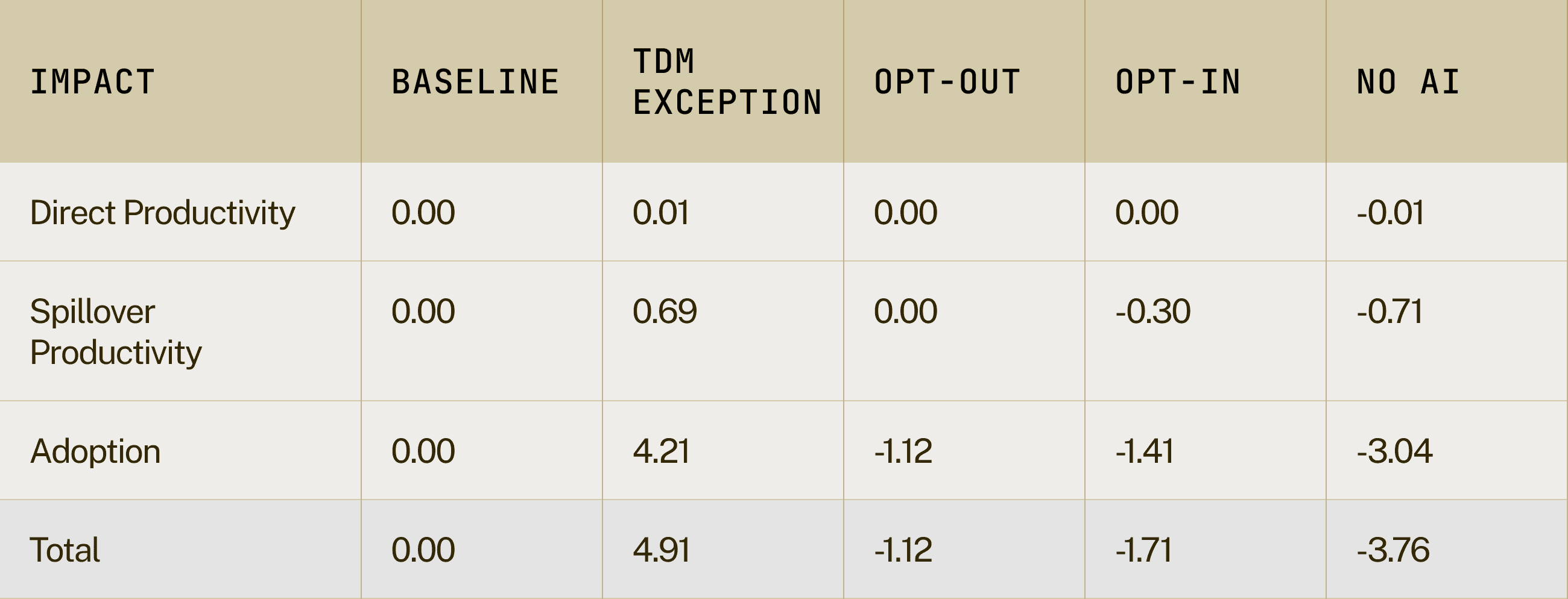

This model evaluates the economic implications of the different AI copyright policy regimes discussed in the piece through a comparative scenario analysis. The framework captures both direct productivity effects and broader economic spillovers from investment on AI infrastructure and sites (which could include both expenditure in tangible and intangible assets as well as establishing locations from which companies operate), and productivity gains from the adoption of AI technology driving productivity increases.

Baseline Framework

The model establishes as counterfactual a scenario in which UK AI investment and adoption patterns maintain parity with UK/EU trajectories as per data in the Stanford AI report and data on the adoption gap relative to the US. This baseline provides a “business-as-usual” framework for evaluating alternative policy paths and their associated economic impacts.

Scenario Design

The model explores four alternative trajectories beyond the baseline, each representing distinct policy choices and their economic consequences:

- Full Use Scenario

- Investment converges to 92.2% of US levels by 2030 on the assumption that companies no longer have to worry about copyright claims.

- Represents an optimistic case for convergence to US levels of adoption with companies being able to develop products locally that better match the needs of UK business.

- Assumes removal of other capability constraints that might limit how much investment takes place.

- Opt-out Scenario

- Assumes the implementation of a copyright regime similar to the EU, which drives the assumption that it maintains EU-equivalent investment growth and does not match US investment rates. There are no productivity or spillover effects from investment as it doesn’t change from the counterfactual.

- Introduces capability constraints through copyright uncertainty to reflect the likelihood that investments in the technology would be very limited and likely not contemplate any form of model training in the UK due to the costs of having to manage opt-out databases.

- Adoption remains constant, but models are introduced more slowly, creating a gap to the frontier. This is captured by calculating the average gap in capabilities (measured through MMLU-Pro benchmarks) between proprietary and open-source AI models. UK/EU would adopt models just below the technological frontier.

- Opt-in Scenario

- This would impose very large costs on the development of models in the UK relative to Europe. The “London effect” is unlikely to match the “Brussels” effect, and while frontier models would eventually be deployed, applications built on the scaffolding of non-compliant models would be limited. We assume no growth in the share of investment in AI as companies would choose to develop in other locations.

- Consequently, the more restrictive regime is assumed to drive a consistent adoption gap relative to the EU of 5% a year: adoption grows at the same pace but is consistently 5% lower. Data on the gap between Europe and the UK on which to extrapolate a gap between the two is limited. This is a conservative assumption of what that gap might be given the larger observed difference between these two countries and the US.

- Productivity effects through direct investment, spillovers, and adoption would all be lower relative to the counterfactual of business as usual.

- No Current Gen AI Scenario

- This scenario models the implications of making the existing suite of models non-compliant with the current UK regime.

- Adoption is assumed to drop to the current market share of open source LLMs, adjusted for the lower adoption rate of these models in the UK/EU. Adoption gradually increases as investment in compliant technology brings new models to market.

- Initial investment collapses to reflect the undesirability of the UK for current model suites and reflecting the growing adoption gap to the EU and the US. This gradually recovers as market incentives for developing compliant models kick in, and it is assumed to eventually converge to the current share of investment relative to GDP over time.

- There is a permanent frontier disadvantage in adoption and model capability relative to the EU, which persists until 2045, even as investment in compliant domestic technology begins to bridge that gap.

Table 8: NPV Net Impacts (£bn) - 5 Years

Table 9: Annualised NPV Net Impacts (£bn) - 5 Years

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]