Table of Contents

- 1. Foreword

- 2. Executive Summary

- 3. The mass transit gap

- 4. Transit, productivity, and land use

- 5. Metro mayors are visible but underpowered

- 6. Campaigners, not builders

- 7. Why construction costs are high and how mayors could cut them

- 8. The solutions

- 9. Devolving consents

- 10. Devolving funding

- 11. Conclusion

- 12. Authors

- 13. Appendix: Draft amendment

Foreword

Britain invented mass transit. Britain built the first tram, the first railway, and the first underground. These spread prosperity around the country, with 200 towns and cities once having a tram network. West Yorkshire used to have over 80 tram routes and more than 200 miles of track. Leeds was one of the final holdouts against pulling up the rails. Our history shows what is possible when infrastructure is treated as the backbone of growth.

In West Yorkshire, we are starting to put that principle back into practice. Last year, I announced that buses will be brought back under local control, with the Weaver Network offering an improved, reliable, and integrated system. West Yorkshire was the first region in England to introduce bus fares caps amid the cost of living crisis, helping people afford the journeys they rely on. We’re investing tens of millions to improve the cycling and walking network so that more people can have safe, sustainable ways to get around.

But progress is held back by an undeniable gap. Leeds remains the largest city in Europe without a mass transit system. And this is wasting potential - not just for Leeds and the rest of West Yorkshire, but the whole country. Too many of our communities are disconnected from opportunity. I’m determined to end this injustice.

The policy suggestions in this report point the way forward. They would allow West Yorkshire and other mayoral regions to become builders. By giving mayors the powers to approve and fund projects, we can speed up delivery, bring down costs, and restore confidence that the government can make working people’s lives better.

When mayors are trusted to deliver, success follows. In Spain and France, mayors have built metro and tram networks quickly and cheaply that have transformed their regions. With the same tools, our city-regions can do the same, connecting people to jobs, attracting investment, cutting emissions, and supporting thriving communities.

This is about more than quick journeys. It is about fairness, economic growth, and restoring trust in politics. By devolving funding and approval abilities, we will give mayors the powers and the responsibility to build.

The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill is a once-in-a-generation chance to unleash a transport revolution across the North and beyond. If we trust local leaders, we can close Britain’s mass transit gap and build the future our regions deserve.

Tracy Brabin

Mayor of West Yorkshire

Executive Summary

The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill should give metro mayors more powers over the construction of new trams, light rail, and underground lines. Mayors are well placed to build regional transport infrastructure projects, but currently lack the necessary powers. To have control over projects, mayors need both approval and funding powers. The Bill should include the ability for metro mayors to:

- Grant Transport and Works Act Orders (TWAOs), which grant planning approval for most tram, light rail, and underground projects. Right now TWAOs are a long, uncertain, and expensive back-and-forth between local promoters and central government. Mayors know their area best and should be able to approve projects for their region. See Appendix 1 for a draft amendment that would grant this power.

- Introduce a tourism levy on visitors as a component of an overnight stay in hotels and short-term lets.

- Improve land value capture, as currently mayors are unable to raise money on the land value increases that accrue to existing landowners. This should be done through allowing mayors to levy business rates supplements without a poll. This learns from London’s Crossrail experience where delivery of the transformational project - funded partially by such a levy - was framed as an investment in the region. A council tax precept could also be considered for properties near new stations who will benefit, expiring once debt from building is repaid.

- Create a Workplace Parking Levy without Secretary of State approval. New parking levies can take up to three years to get the sign off from the Transport Secretary. This should be fully devolved to local authorities and metro mayors as it is ultimately a regional matter.

- Use the integrated settlement better. Currently, any schemes worth £200m or more over the life of the scheme have to be approved by the Department for Transport (DfT). This limit should be scrapped. It makes little sense for the DfT to be approving business cases for tram extensions when the places themselves have more knowledge and experience.

- For major schemes which still require central approval or funds, avoid the iterative process of comments through layers of government until they reach the Treasury. Instead, utilising the Treasury Approvals Process, schemes should agree an expedited approvals and assurance plan with just two approval points: a joint approval between the scheme developer and the DfT and a joint approval between the Treasury and the Cabinet Office.

The current state of transit and productivity in Britain’s cities:

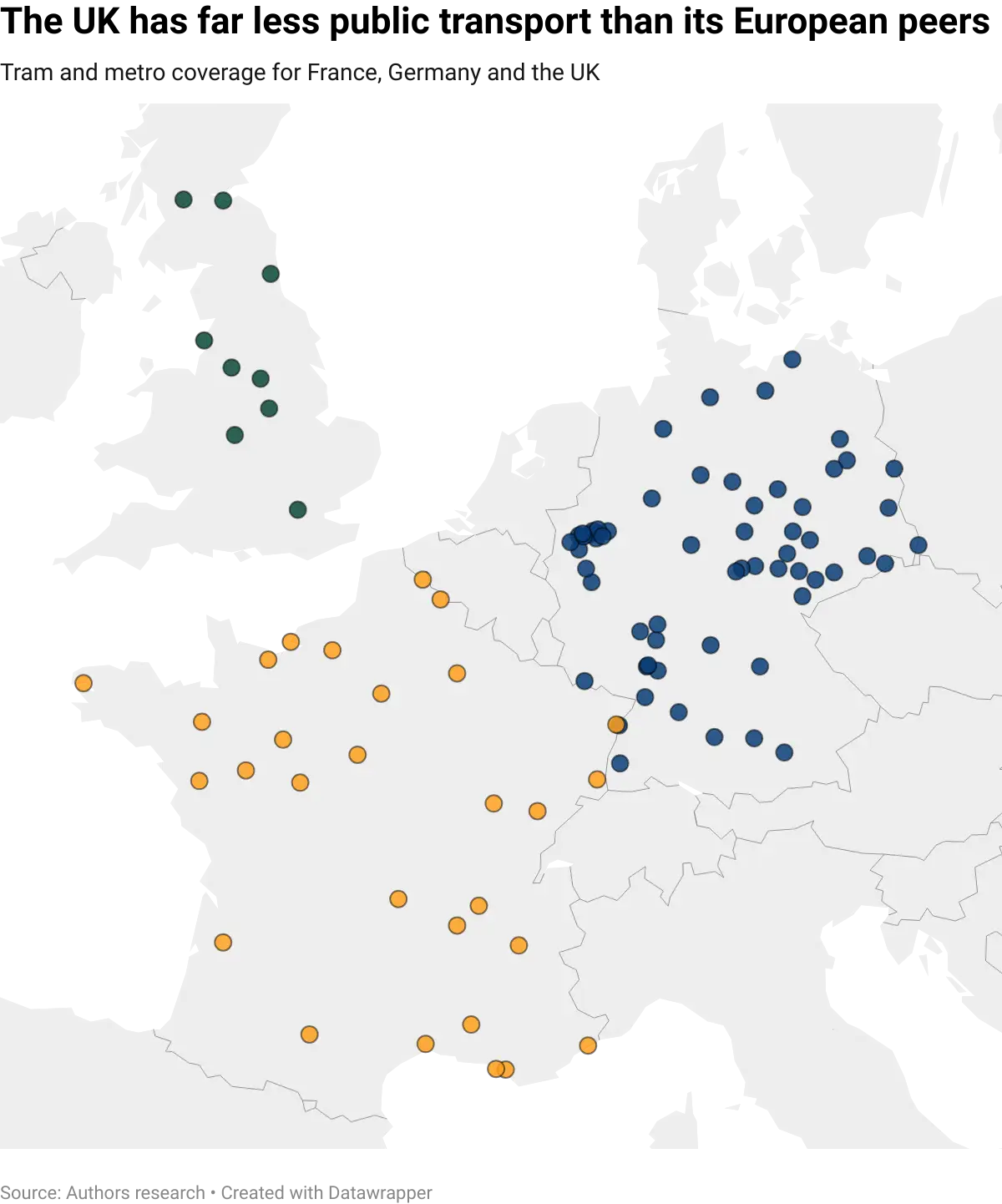

- Despite a long history of world leading transport projects, the UK currently has a mass transit gap. Only nine British cities have a tram or metro, compared to 30 French cities and 60 German cities. Every French city with a population above 150,000 has a tram or metro, that’s the equivalent of Newport, Peterborough, or Dundee.

- Cities tend to be more productive because they have larger labour markets that let people specialise. But Britain is an outlier, with cities, except London, being less productive than the national average.

- This is because Britain’s cities are smaller than they appear. Far fewer people can get to city centres using public transport or private cars than similar cities in Europe and America, which shrinks labour markets and reduces productivity.

- Mass transit is needed to encourage improved land use and regeneration projects in Britain’s cities. The density that enables a larger labour market and agglomeration can only be supported by mass transit as it can effectively move more people in and out of our cities.

The role of metro mayors:

- Metro mayors are visible champions for their regions, but are underpowered. The current model erodes public trust every time a mayor calls for a project and Westminster turns them down. People stop believing that the government can deliver infrastructure.

- While Mayors in America, France, and Spain all have significant fundraising powers, mayors in England are reliant on central grants for most of their funding.

- Since funding and approval for new transport projects sits in Westminster, mayors are campaigners, not builders. They must generate publicity for their projects rather than having the power to actually build them.

- The current model also raises construction costs because no one person is politically responsible for the project. Madrid saw a boom in metro building because their regional politicians could run on pledges of building new tracks and then had the power to approve, fund, and oversee their construction.

- French mayors also demonstrate the power of giving local politicians the power to deliver transport upgrades. Their tram renaissance, with 21 cities building trams just this century, has been fuelled by mayors making electoral pledges and then having the power to deliver them.

To deliver the infrastructure Britain’s cities need, we need to empower metro mayors. We need to give them the ability to approve and fund their own projects. When France and Spain put local leaders in charge, systems got built quickly and cheaply, and voters rewarded the results.

The construction boom will boost productivity and raise living standards across the UK, while reducing the pressure on the Treasury to fund every single local project. The payoff is practical and popular: faster commutes, wider access to jobs, cleaner air, and visible progress on growth.

Mayors should be able to determine Transport and Works Act Orders and fund schemes with a mix of revenue raising tools. The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill should give metro mayors the ability to build the future.

This paper was published jointly with Labour Together, a think tank offering bold ideas for Britain under a Labour government.

The mass transit gap

Britain invented mass transit. The world’s first tram carried passengers between the quarries of Mumbles and the city centre of Swansea. The world’s first passenger railway opened between Stockton and Darlington in 1825. Five years later, the world’s first inter-city passenger railway opened between Liverpool and Manchester.

London’s Metropolitan Railway was the first underground passenger railway and its nickname ‘metro’ spread the world over. Before any other city had built an underground, London’s City and South London Railway opened, which was the first deep-level electric underground railway. By the early 20th century, more than 200 British towns and cities had a tramway.

More recently, the Victoria Line was the world’s first automatic passenger railway. Runcorn, a new town in the North West, was designed around the world’s first bus rapid transit system, which opened in 1971.

Yet as the 20th century went on, Britain stopped building. Tramways were ripped out, replaced by heavy traffic into our cities and lower capacity buses. The Beeching cuts withdrew railway service to over 2,300 stations, cutting off many villages and towns from the national network. Despite promising innovations like the automatic Docklands Light Railway that repurposed old lines, these failed to spread around the country.

Today, new projects are held up in years of delay in the planning system and struggle to get funding. Endless wrangling between local promoters and central government over approvals and money empowers blockers and frustrates metro mayors who are eager to build.

The failure to build has caused a mass transit gap. Only nine British cities have a tram or metro, compared to 30 French cities and 60 German cities.

Every French city with a population greater than 150,000 has a mass transit system, while there are 30 British towns and cities larger than that that go without. If Dundee, Peterborough or Newport were French, they would all have a tram system.

An FT cross-country comparison found the large UK cities, of 250,000 people or more, were the least likely to have mass transit. Only 15% of British cities have a tram or metro, trailing 100% of Danish cities, 88% of German, and even heavily car-dependent America at 21%.

The national failure to build has severe local consequences.

Transit, productivity, and land use

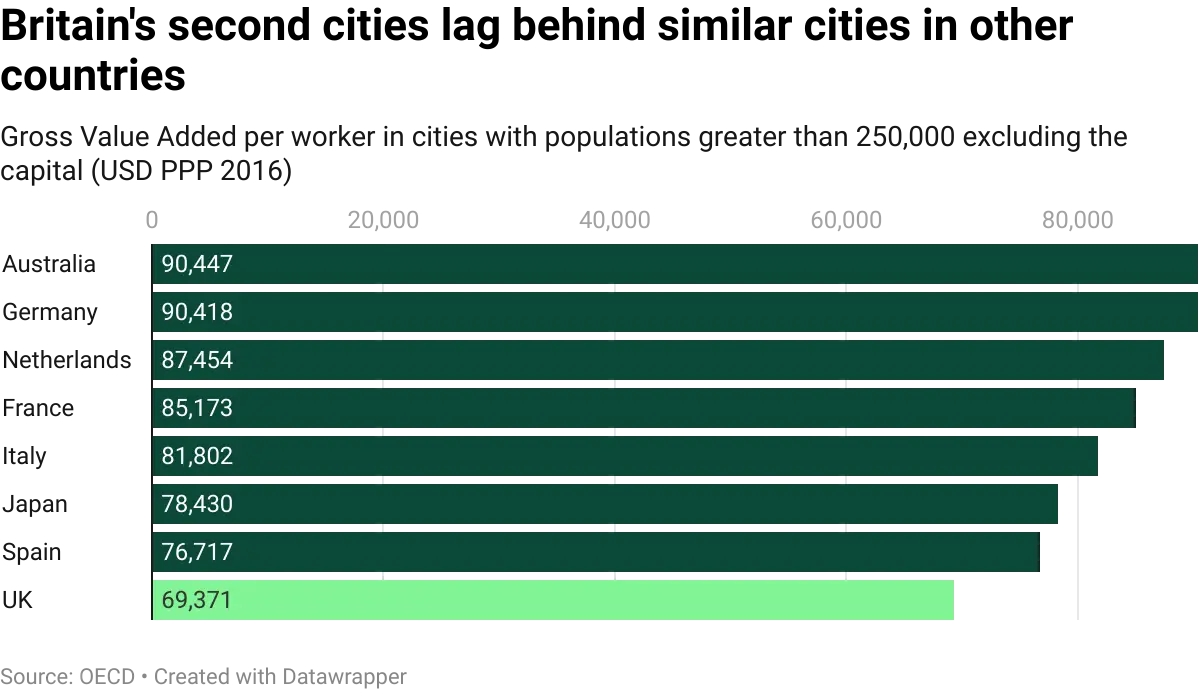

Outside capitals, cities in rich countries tend to beat the national average productivity because large labour markets let people specialise.

But Britain is an outlier. Our cities, except London, are actually less productive than the national average. Output per worker in these cities is only 86% of the UK average. These cities’ productivity is 30% lower than German peers, 23% below French peers, and 18% less than Italian peers.

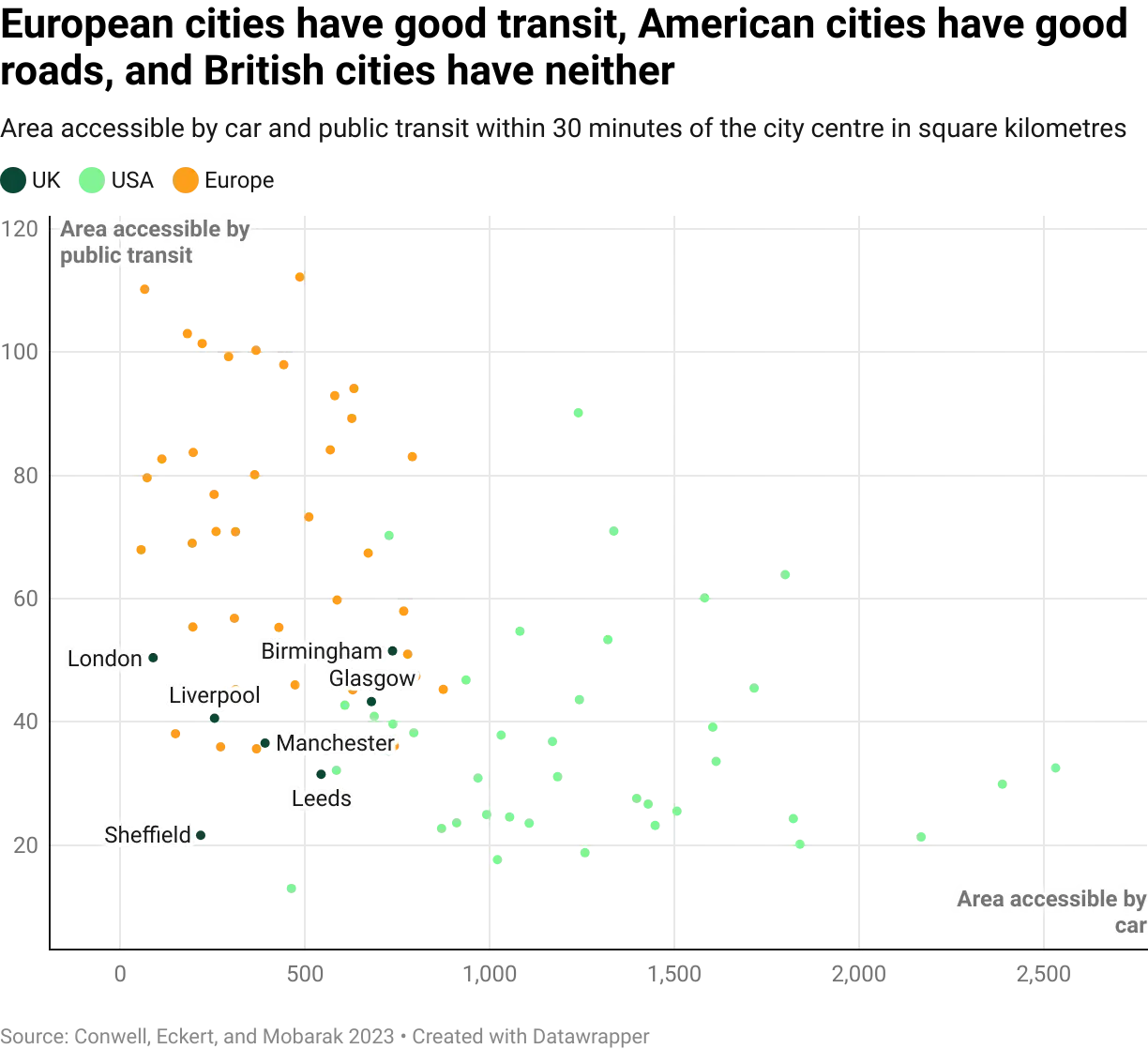

Britain’s cities are effectively made smaller by the lack of mass transit. Leeds and Marseille are about the same size. Yet while Leeds is the largest city in Europe without any mass transit, Marseille has two metro lines and three tram lines. Consequently, only 38% of Leeds residents can reach the city centre within 30 minutes, while 87% of Marseille residents can. Partially as a result, the average Marseille resident is roughly 20% more productive than the average Leeds resident.

Even British cities that do have a mass transit system, like Sheffield, Manchester, and Glasgow, underperform on accessibility. All of these cities are in the bottom quintile of European cities by land area that is transit accessible within 30 minutes from the city centre. In fact, British cities make up half of the bottom 20%.

The average area accessible by mass transit in 30 minutes in British cities, outside London, is 37 square kilometres, effectively the same as the American average of 34 square kilometres. That’s far below the European average of 63. Yet American cities make up for this gap with easy accessibility for cars on interstate highways. The average American city has 1,160 square kilometres accessible within a 30 minute drive, compared to 428 for the average European city and 470 square kilometres for a British city. The UK has the worst of both worlds: its cities are constrained by American level public transit but lack American level car infrastructure.

Mass transit, whether it be trams, light rail, or a metro, enlarges labour markets, which drives specialisation: workers have more job options and can earn higher wages. For example, the Elizabeth Line’s opening boosted the number of jobs accessible within 60 minutes by public transport by 11% for the Abbey Wood branch and 62% of surveyed passengers reported better access to job opportunities.

The even bigger prize is better land use. Mass transit supports denser and more vibrant city centres with more space for new businesses and housing by building up. Undergrounds can carry 30 times more people per hour than a lane of traffic used by cars. Moving more people around a city centre enables it to build upwards and expand the local labour and housing markets.

The Jubilee line extension, opened in 1999, meant that an additional one million people were now within commuting distance of the average station. Jobs along the route rose by 52,000 between 1998 and 2000, a jump of 15%, with a further 30,000 created at Canary Wharf in the following four years. One study found that the extension boosted nearby firms’ productivity by 15%. Local population around the new stations rose by 31%, compared with an 11% baseline rise, benefitting from the strong housing growth enabled by the transport line.

Likewise, trams have been the catalyst for regeneration projects. As a permanent and visible investment that improves accessibility, projects can unlock transformational private investment. In Greater Manchester, the Salford Docks used to be the third-busiest port in Britain, but decades of falling traffic shuttered them in 1982. The Manchester Metrolink arrived in 1999, prompting the redevelopment into a new business district. The Salford Quays have seen output double in the two decades since the tram arrived with 1,250 businesses in the area employing more than 30,000 people. The area’s population has quadrupled as the tram supports new residential developments.

These benefits are achievable across Britain’s cities and large towns if only we made it easier to build. This begins with empowering metro mayors.

Metro mayors are visible but underpowered

Metro mayors are new, but increasingly widespread. Labour’s 1997 manifesto pledged the creation of a mayor of London, subject to a referendum, which passed with 72% of the vote in 1998. Labour then established combined authorities in 2009 and the Conservatives legislated in 2016 for directly elected mayors to chair them. This paved the way for the election of 6 metro mayors in 2017, with a total of 14 now in power covering over half the population of England.

Metro mayors have gained significant visibility, but their powers are constrained by central government rules, and ringfences on funding. Compared with peers abroad, they have few levers to actually raise revenues themselves.

For example, the Mayor of New York City controls property taxes, a sales tax, and an income tax, which together bring in over $60bn. Mayors in England control very little. Their powers over Council Tax are limited to specifying how much to levy on Band D properties (with no control over bands or the rates themselves). Some of them are allowed to retain some Business Rates, but this is at the whim of central government. They have the power to implement a Business Rates Supplement, but this is limited by referendum and other statutory requirements. And they are only now about to get the power to charge a Mayoral Community Infrastructure Levy, paid when new planning applications are approved. They have no ability to influence sales or income taxes.

So whilst the NYC mayor has tax revenues of around $60bn, the Mayor of London has little more than £5bn comprising council tax of £1.6bn and retained business rates of £3.7bn.

Instead of having the power to finance projects and build, mayors are left reliant on central grants. It is the same story with granting planning permissions for new tram and tube lines. Mayors can champion a scheme, but they cannot approve the project. Instead, they depend on central government for the planning approval process.

Campaigners, not builders

Despite the expansion of metro mayors and ‘Transport for City Regions’ programme that helps some places, funding and approval for new transport projects sits with Westminster. Mayors are often forced to spend years lobbying for money, first to fund business cases, then for the planning process, and finally to actually build the line. Each step invites delay and the possibility of rejection.

Mayors are therefore campaigners rather than builders. Andy Burnham, the mayor of Greater Manchester, has called for an underground system for Manchester. The specifics of the proposal have not been announced yet, and there’s no clear delivery timeline. Given that the mayor does not have the power to fund, approve, or deliver such a scheme, its progression is completely dependent on what central government decides.

This is not the first time Manchester has tried to build an underground. In the 1970s, Transport for Greater Manchester’s predecessor released plans to connect Manchester Piccadilly and Victoria stations with a Picc-Vic tunnel. The scheme died because central government did not want to fund its £9.3mn construction cost (£100mn inflation adjusted). The gloomy state of the central government’s finances doomed the project, and there was no local champion who could fund and oversee the project instead. Metro mayors, if given the powers to fund and approve projects, could fill that gap.

Similarly, Sir Sadiq Khan has long campaigned for a Bakerloo line extension in London. Despite being mayor of one of the most prosperous cities in the world, he lacks the ability to fund or approve such a line. His initial election manifesto in 2016 included a pledge to secure the extension to Lewisham and beyond. Throughout the past 9 years, Sir Sadiq has advocated for funding from the DfT and Treasury. Yet no concrete pledges have materialised, and the anticipated opening date of the extension has slipped to 2040 at the earliest.

The campaigner model created by Whitehall means that metro mayors are effectively rewarded for their ability to generate publicity rather than actually building new infrastructure. Without the ability to build, mayors spend their time and effort loudly demanding more money from Westminster. This increases mayoral pledges for projects that will not be delivered. Every time a mayor calls for a project and Westminster turns them down, anger towards the central government and the Treasury increases, potentially bolstering the mayor’s electoral position, but no progress is made towards ending the mass transit gap.

This erodes trust. When projects are over-promised and delayed or cancelled, people stop believing that the government can deliver infrastructure. The Bakerloo line extension’s first consultation was 11 years ago. The project is years from any spade in the ground and likely 15 years from opening. Leeds still lacks a tram, more than 40 years after plans were first created.

This lack of delivery strengthens political narratives about “forgotten” or “left-behind” regions. This scepticism can turn to distrust and resentment towards the centre, or even political power in general. At its core, this is distrust that the government can ever improve working people’s living standards.

The current system also slows construction and raises costs meaning fewer projects are built, as described in the next section.

Why construction costs are high and how mayors could cut them

In the run up to the 1995 regional elections in Madrid, the Partido Popular (People’s Party) promised to build 30 miles of new metro by the end of their four year term. By the 1999 elections, they had actually delivered 35 miles. Unsurprisingly, they were re-elected with an increased majority, and the PP have won every regional election in Madrid since.

This can be contrasted with the centrally restricted electoral promises of the recently re-elected Mayor of West Yorkshire, Tracy Brabin. She pledged that by the end of her four year term, construction would begin, not finish, on a new tramline in Leeds.

Given the lack of power that metro mayors have over transport approvals and funding, Brabin’s electoral pledge is actually ambitious. Britain’s tramlines often have to wait nearly a decade to gain the necessary approvals and funding from central government to begin construction, so a four year approvals process would be an impressive accomplishment. But if we want to see Madrid-level building, we need to get decision-making, approvals, and funding at the right level for local transport projects.

Politicians care about winning elections. Given their local impacts, a local transport project will generally not be a decisive issue in a national election, which means that national politicians do not (except individually, for their area) have strong incentives to focus on delivery. Instead, they will focus on the national issues that could be decisive, like defence, the NHS, and the economy.

There are times where infrastructure in marginal seats can make a difference. An example might be HS2 having to tunnel through the Chilterns, rather than run above ground. But when the national government is funding a local project for these political reasons, there is generally no salient voter group that is pushing to keep costs down.

Since there is no group of voters who, at the national level, care about both the project being built and also about the time and money it takes to build it, there is no accountability. No individual politician is directly threatened by higher costs or a failure to deliver local transport projects. This means there is no political pressure to keep costs down, despite the huge cost to the Treasury.

In contrast, in regional elections, delivery can make or break electoral outcomes. Before the metro expansion pledge, the PP had never won a Madrid regional election. Since construction began on the metro expansions, they have won eight elections in a row. The opening of the lines was arranged to maximise their political effectiveness. In 1999, 2003, and 2007, there was a spate of openings of new lines and stations in the run-up to the regional elections in each of those years, allowing photo-ops and demonstrations of the success of the incumbent government ahead of the vote.

The same pattern holds in France, where 21 cities have built tramways in this century alone. This surge in building has been powered by local mayors.

Strasbourg offers another example. It is about the same size as Coventry, and was an early tram adopter. Ahead of the 1989 mayoral election, Socialist candidate Catherine Trautmann made the tramway the centrepiece of her campaign. Despite Strasbourg traditionally electing centre-right mayors, Trautmann won the election and was given a mandate to build.

French mayors, with the support of their municipal council, can levy a versement transport (VT), which is a payroll tax of between 0.9% and 2.85% that is ring-fenced for transport spending. The VT enabled the funding of the tram extension at a local level. Given the strong political support and the guarantee of local funding, the planning process commenced quickly. A public inquiry followed that was shortened given the political support of the plans.

France still reserves a role for the national government in planning local infrastructure, but this is done through Prefects, which are the national government’s representatives in a region. This local link encourages faster delivery compared to the ministerial system in the UK. The entirety of the planning process in Strasbourg took two years, and construction took another three years. The opening proved a success, and Trautmann was re-elected the next year. In the following term, the Strasbourg tram continued to expand and it now has six lines and 30 miles of track, making it one of the most extensive systems in Europe.

France and Spain have both given local politicians the power to deliver transport upgrades. In turn, this has also given them the responsibility to deliver. If they fail to live up to their building promise, voters will hold them accountable at the next election, further incentivising delivery. Once projects are complete, voters can reward successful politicians with re-election.

Since delivery matters for these politicians, and the money mostly comes from the tax that they are able to raise, they are willing to make trade-offs to speed up construction and lower costs. When projects are funded with national money (i.e. someone else’s money, from the locality’s perspective), as is the case in Britain, there is much less of an incentive to make trade-offs and control costs, which can otherwise be extremely high.

Cheaper delivery is possible. Underground lines cost only one sixth as much in Spain per mile than in Britain, and French trams are half as expensive as British ones. Delivery can also be much faster. Madrid built upwards of 35 miles in a four year period, and French cities deliver whole tram networks in a similar time period. In Britain, a one mile extension to Birmingham’s tram network is taking 16 years. The Birmingham Eastside Extension project, discussed below, spent nearly as long waiting for ministerial sign off (3 years and 4 months) as the French and Spanish projects took to plan and build (4-5 years).

The solutions

The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill provides a generational opportunity to turn metro mayors into builders. With a few targeted amendments, the bill could devolve approval for transport projects and funding powers to the city-regions, which could usher in a British transport renaissance. This bill is the best opportunity to empower metro mayors, and we may not see another opportunity like it in this Parliament.

Devolving both approval and funding powers will make it easier to build mass transit projects.

With metro mayors raising their own funding, new transport projects will take pressure off the Treasury, who are currently on the hook for most transit projects and responsible for cost overruns. The cost of building infrastructure will fall, as a result of aligning the political incentives of metro mayors with cheap and quick delivery.

Devolving consents

Trams, light rail, and most underground lines are currently approved through Transport and Works Act Orders (TWAOs). Established in 1992, the TWAO process was designed to streamline transport scheme approval by replacing the need for individual Parliamentary Private Bills. Instead, promoters, which are typically local authorities or transport bodies, apply to the Transport Secretary.

TWAOs provide valuable powers to promoters, such as compulsory purchase of land, construction approvals, and the options to introduce penalty fares, which underpins fare-raising. Yet the TWAO process is currently long and centralised.

For example, the Birmingham Eastside Extension is a one mile tram extension to link up with the future HS2 station. The West Midlands Combined Authority started work on the proposal in 2010. But the TWAO application was not submitted until October 2016. The Transport Secretary didn’t approve the TWAO until January 2020. Preparatory work began in June 2021 and the line is expected to open next year. From start to finish then, it will take 16 years to build one mile of track.

There are several reasons why the TWAO process is so long. For one, there is little incentive to move quickly, as the responsibility for the process is held by the Department for Transport, while local promoters are the ones who bear the immediate costs of delay. The process is further slowed by the back-and-forth between central government and the local promoter, which drags out the process through clarifications, funding arrangements, and negotiating the conditions for approval. There is also a large amount of documentation needed for TWAOs, including environmental statements, traffic analyses, and various consultations, both statutory and pre-application. In total, the Birmingham Eastside Extension had to fill out 5,718 pages of paperwork. If printed out, this paperwork would be the same length as the tram extension itself.

The Government’s new Planning and Infrastructure Bill (PIB) will improve the TWAO process. No longer will anyone who is a statutory objector be given automatic right to force an inquiry. Instead, the Secretary of State will be able to reject calls for an inquiry, unless they consider the objection serious enough to merit the added delay that an inquiry brings.

The PIB also includes tweaks that should speed up the process, by clarifying that the applicant pays for the inquiry unless there are good reasons to the contrary, and that the statutory consultees can charge fees for their involvement in the process. These will both avoid delays caused by bickering over costs of participation in the process.

Finally, the PIB will impose decision timescales similar to the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP) process, where ministers are given three months to make a decision. But this won’t be a silver bullet, as NSIPs are often subject to ministerial delays. In fact, of NSIPs that have been due for a decision since 2023, 55% of them have been delayed beyond the three month time window during which the Secretary of State is supposed to decide on the project.

However, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill stops short of empowering mayoral authorities to approve or fund transport projects.

This is where the English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill could be the difference maker for local transit. We propose that there should be an option for established mayors with an integrated settlement to grant TWAOs. A project should be allowed to choose to either apply for their TWAO from their metro mayor or from the Secretary of State.

Giving metro mayors a parallel power to grant TWAOs would also give them the responsibility to deliver infrastructure. Consenting would no longer have to be a drawn out process between the local promoter and central government, but instead it would be up to metro mayors to chart a vision for their region, and they would also have the power to make it happen. They can draw on their local knowledge, which is often lacking in central government.

TWAOs contain significant documentation, so it is important that mayors have the necessary resources to handle applications. This can be resolved by the funding devolution described in the next section. There should also be protections for property owners in line with existing protections for national schemes.

One argument against devolving an additional approval power to metro mayors is that they will often have a conflict of interest when it comes to approving schemes, given that the combined authority could be a promoter. However, this objection does not pass scrutiny.

First of all, metro mayors gain their authority based on the vision that they sell to voters. If a metro mayor runs on a pledge to build a tramline, and voters respond enthusiastically by electing them, then the metro mayor has a democratic mandate to grant a tram project a TWAO. Those opposed to the project are opposing the wishes of the electorate who voted for the mayor. Politicians should have the power to deliver on the promises that they make to voters.

Second, there are already many instances where groups within a bureaucracy gain planning approval from the leader of that same bureaucracy, and we do not generally consider there to be a conflict of interest. Local authorities regularly grant themselves planning permission for new schools or council housing. On the national level, both National Highways and Network Rail are ultimately responsible to the Transport Secretary: their road and rail projects are also given planning permission by the Transport Secretary. Metro mayors could use a similar legal arrangement for transport projects where the promoter of the scheme is legally distinct, but still accountable to the mayor.

Ultimately if metro mayors deliver a poor scheme, they will be held accountable by the electorate at the next election, incentivising them to deliver well-thought-through projects.

See Appendix 1 for a full amendment on how to devolve Transport and Works Act Orders. This should be added to the English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill.

Devolving funding

In addition to planning approval powers, giving metro mayors the ability to fund projects is key to unlocking a British public transport renaissance. Projects would no longer be held up while waiting for Treasury funding, and likewise, the Treasury will now be off the hook for any potential expensive overruns.

Each region and project is different, so a one-size-fits-all approach to funding projects will not work. Instead, the Government should give metro mayors different options for ways to raise money within their regions, and let mayors choose which ones work best for their context. This encourages experimentation, where different regions can learn from each other about which funding mechanisms work best.

Such changes would be well-received by mayors: Metro mayors have made efforts to become more than campaigners; they have been vocally asking for more revenue raising powers to fund their priorities.

The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill does include provisions to allow mayors outside of London the power to issue development orders, create development corporations, and collect a community infrastructure levy. These are all positive steps and will help with funding infrastructure. Further reforms to funding would be going with the grain of the bill. But more options need to be considered if mayors are able to self-finance significant developments. Below are some options for mechanisms that should be given to metro mayors to raise funding for local transport schemes:

Tourism levies

Major cities like Amsterdam, Paris, Barcelona and Rome all charge tourist levy on hotel stays. Tourists benefit from a city’s transport infrastructure, but barely contribute to its construction. A modest levy ensures that visitors help contribute to the infrastructure that they use, while also improving the visitor experience.

The Scottish Parliament passed the Visitor Levy (Scotland) Act 2024, which empowers local authorities to introduce a levy on overnight stays. Edinburgh plans to introduce such a levy in 2026. Such levies do not require approval from the Scottish Parliament or Ministers.

In England, local authorities and metro mayors lack this power. The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill is the chance to fix this. Mayors should be given the power to set their own tourist visitor levies, which would apply also to short term lets such as Airbnbs (which often do not pay VAT). Mayors would not be obligated to do so, but would have the option.

Mayors have estimated that such a charge could raise upwards of £40m a year for Greater Manchester and £240m a year for London. In Manchester, that revenue would be enough to unlock potentially £500m-£750m of capital investments. In London, the revenue could fund the Bakerloo line extension in its entirety, if it were built at Northern line extension costs.

Land value capture

When new transport projects are built, the neighbouring land increases in value. Tram projects in Manchester, Edinburgh, and the West Midlands saw house prices rise by around 15% near the line. The Jubilee line extension increased land values by 52% relative to controls. A Savills analysis found that the Bakerloo Line Extension would generate up to £25bn in increased land value, adjusted for inflation, enough to pay for the line five times over.

The same analysis found that between ⅔ and ¾ of the land value increases go towards existing stock, with the rest being new developments alongside the stations. There are ways for mayors to capture some of that land value increase on new developments through a mayoral community infrastructure levy (MCIL). MCIL has raised £1.33bn so far to help cover the debt from the construction of Crossrail. The power to levy it will expand to all metro mayors with the English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill.

But there are currently no ways for metro mayors to capture the vast majority of uplift that accrues to existing property owners. The goal should not be capturing all of this uplift because some property value increase should be the reward that residents get for putting up with disruptions during construction. But none of these uplifts are possible without the infrastructure itself.

To do this, metro mayors could be allowed to charge a council tax precept specifically for funding new infrastructure. This charge whould be only on properties near the new stations and should expire once the debt from building the project is repaid. Given the increase in house prices near stations and the improved connectivity, a targeted precept is reasonable.

Alternatively, there have been proposals to merge stamp duty and council tax into a property tax. If this happens, there should be an opportunity for mayors to control some of this new tax to help fund local infrastructure.

Business rate supplements

The Business Rate Supplements Act 2009 gave the power to certain local authorities (Greater London Authority, county councils, and unitary councils) to increase business rates locally up to 2p for every £1 of rateable value. These powers have since been extended to most metro mayors as part of their individual devolution deals.

However, business rate supplements have only been used once in the UK. The supplement enabled £4.1bn of borrowing for Crossrail and raises about £250mn each year.

One of the barriers to increasing use of business rates supplements is the requirement for it to be approved by a ballot of businesses. This was introduced by the Localism Act 2011 after London had already started to use the power for Crossrail. The ballot increases the political salience of the supplements and has never actually enabled any supplements to be introduced. The requirement to run a ballot should be scrapped entirely.

To help with the politics of increasing business rates, metro mayors should learn from London and tie the increase to the specific delivery of a transformational project. Clearer links between the additional tax and the project will help to frame it as an investment rather than just another charge. Supplements only apply to businesses that meet a minimum rateable value. Metro mayors have the option to increase this minimum value if they think smaller businesses would be unduly harmed by a supplement.

Workplace parking levies

The Transport Act 2000 gave local authorities the power to adopt a workplace parking levy (WPL). In 2012, Nottingham became the first and only authority to introduce a WPL, which raises around £9 million a year for the city. The WPL charges employers per parking space over a minimum of 10, which is often passed to employees. Nottingham’s levy enabled 10.5 miles of new tramway to be built combined with additional funding from the Treasury.

The challenges are that WPLs take several years to implement and that if another city wants to adopt a WPL, they have to get the approval of the Transport Secretary. The total process could take up to three years or almost an entire mayoral term. Additionally, it is currently just a power that local authorities have, which means a metro mayor cannot implement one across their region.

The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill should change this, by fully devolving the power to implement a WPL to local authorities without the need for Transport Secretary approval. Where there is a mayoral strategic authority, the power to implement a WPL should be primarily the metro mayor’s.

A similar principle applies to road user charging, which should also be a power that rests with metro mayors. There are smaller road consents that still require Secretary of State approval like traffic enforcement powers and lane rental schemes. These were mentioned in the devolution white paper, but have not been added to the Bill yet.

Better use of the integrated settlement

Where some central funding is still required for local projects, the current funding approvals system is inadequate. For strategic authorities with an integrated settlement, the regulation which requires any schemes worth over £200m over the life of the scheme to be approved by the Department for Transport should be scrapped or increased to £1bn (the threshold above which projects are not allowed within the integrated settlement). It makes little sense for the Department for Transport to be approving these business cases for tram extensions when the places themselves have more knowledge and more experience. Witness Greater Manchester’s delivery of the Trafford Park line in 2020, which came in on budget and ahead of schedule.

For major national schemes which still require central approval, projects should not be expected to go through an iterative process of comments through different layers of government until they reach the Treasury. Instead, utilising the Treasury Approvals Process, schemes should agree an expedited approvals and assurance plan with just two approval points: i) a joint approval between the scheme developer and the Department for Transport and ii) a joint approval between HM Treasury and the Cabinet Office.

Conclusion

Britain’s mass transit gap is a result of our failure to build and makes our cities poorer. With centralised funding and approvals, mayors cannot get on and build but instead have to campaign endlessly for money. The current system erodes public trust and pushes up costs. Where France and Spain put local leaders in charge, systems got built quickly and cheaply, and voters rewarded results.

The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill should give English mayors the same levers. Let mayoralties determine Transport and Works Act Orders for local schemes. Combine that with a menu of revenue raising tools, including visitor levies, council tax precepts, business rate supplements, workplace parking levies and an improved use of integrated settlements.

Local leaders will then approve, fund, and manage construction of schemes. With power comes responsibility to deliver. Successful mayors will get on and build and then be rewarded by voters with re-election.

With these powers, projects like a Manchester underground and a Leeds tram stop being press lines and start being work sites. The payoff is practical and popular: faster commutes, wider access to jobs, cleaner air, and visible progress on growth. Give mayors the tools and England’s cities can build again.

Appendix: Draft amendment

Draft amendment to will give promoters the option to apply to metro mayors for a Transport and Work Act Order in addition to the Secretary of State

“1. (1) The Transport and Works Act 1992 is amended as follows.

(2) In section 1—

(a) in subsection (1)—

(i) for “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(ii) omit “, so far as it is in England and Wales”;

(b) after subsection (1), insert —

“(1ZA) In this Part, “relevant authority” means—

(a) in relation to an order for a scheme located in England & Wales, the Secretary of State; and

(b) in relation to an order for a scheme wholly located in the area of a mayoral combined authority, the elected Mayor of that authority or the Secretary of State,

and, where relevant and without limitation, provisions of this Act are to be construed—

(i) to allow applications under section 1 or 3 to be made to and determined by either the Secretary of State or the elected Mayor except that once an application is made, that application must be determined by the authority which has received the application; and

(ii) to permit an elected Mayor to carry out functions in relation to such an application or determination which would have otherwise been carried out by the Secretary of State on the date this Act came into force, excluding any power to make regulations or rules under this Act or any power under section 23 (Exercise of Secretary of State’s functions by appointed person) of this Act. ”

(3) In section 3—

(a) in subsection (1), for “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(b) in subsection (2), for “The Secretary of State shall not make an order under this section if in his” substitute, “The relevant authority shall not make an order under his section if in its”.

(4) In section 5—

(a) for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(b) in subsection (4)(b), for “him” substitute “it”.

(5) In section 6—

(a) in subsection (1) for “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(b) in subsection (1), for “him” substitute “it”;

(c) in subsection (4), for “he” substitute “it”;

(d) in subsections (3) and (7), for each reference to “relevant authority” substitute, “relevant body”;

(6) In section 6A, in subsections (1)(a), (1)(b), (1)(c) and (2)(a), for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute, “relevant authority”;

(7) In section 9—

(a) except in subsection (6), for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(b) in subsection (1)—

(i) for “he” substitute “it”;

(ii) for “his” substitute “its”;

(8) In section 10—

(a) except in subsection (1), for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(b) in subsections (3) and (5) for “he” substitute “it”;

(9) In section 11—

(a) for subsection (1) substitute—

“The relevant authority may cause a public local inquiry to be held for the purposes of an application under section 6 above and the Secretary of State may cause a public inquiry to be held for the purposes of a proposal by the Secretary of State to make an order by virtue of section 7 above.”

(b) in subsections (2) and (3), for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(10) In section 13—

(a) in subsection (1), for “Where an application has been made to the Secretary of State under section 6 above, or he proposes to make an order by virtue of section 7 above, and (in either case) the requirements of the preceding provisions of this Act in relation to any objections have been satisfied, he”, substitute, “Where an application has been made to the relevant authority under section 6 above, or the Secretary of State proposes to make an order by virtue of section 7 above, and (in either case) the requirements of the preceding provisions of this Act in relation to any objections have been satisfied, the relevant authority”;

(b) in subsections (2) - (4)—

(i) for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(ii) for each reference to “he” substitute “it”;

(iii) for reach reference to “him” substitute “it”;

(iv) for each reference to “his” substitute “its”.

(11) In sections 13A - 13D, for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”;

(12) In section 14— (a) except in subsections (4A) and (5), for each reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”; (b) for each reference to “he” substitute “it”; (c) for each reference tco “him” substitute “it”;

(13) In section 14A— (a) in subsection (7)(b) for the first reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”; (b) in subsection (8), in the definition of “appropriate national authority” for the first reference to “Secretary of State” substitute “relevant authority”

2.(1) The Town and Country Planning Act is amended as follows.

(2) In section 90(2A), for “Secretary of State” substitute “person making the order”.

3.(1) The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 is amended as follows.

(2) For section 12 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, substitute—

“Reference of certain applications

12.—(l) The Secretary of State may give directions requiring applications for listed building consent to be referred to him instead of being dealt with by the local planning authority.

(2) A direction under this section may relate either to a particular application, or to applications in respect of such buildings as may be specified in the direction.

(3) An application in respect of which a direction under this section has effect shall be referred to the Secretary of State accordingly.

(3A) An application for listed building consent shall, without any direction by the Secretary of State, be referred to the relevant authority instead of being dealt with by the local planning authority in any case where the consent is required in consequence of proposals included in an application for an order under section 1 or 3 of the Transport and Works Act 1992.

(3B) In subsection (4) “relevant authority” has the same meaning as in Part 1 of the Transport and Works Act 1992.

(4) Before determining an application referred to him under this section, the Secretary of State shall, if either the applicant or the authority so wish, give each of them an opportunity of appearing before, and being heard by, a person appointed by the Secretary of State.

(4B) Subsection (4) does not apply to an application referred to the Welsh Ministers under this section instead of being dealt with by a local planning authority in Wales.

(5) The decision of the Secretary of State on any application referred to him under this section shall be final.”

4. (1) The Planning (Hazardous Substances) Act 1990 is amended as follows. (2) In section 12(2), for “Secretary of State” substitute, “person making the order”.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]