Table of Contents

- 1. Executive summary

- 2. The political case for going big on Ox-Cam

- 3. What needs to happen

- 4. The delivery plan

- 5. Authors

Executive summary

The 100 mile corridor between Oxford and Cambridge is one of the most exciting stretches of land on the planet. Machines there are discovering new gene therapies and scientists are building engines for space travel.

If the region grows in the next 25 years as fast as Silicon Valley did in the last quarter of a century, it will be a major source of cash for public services and a gateway for technology and investment into the rest of the country. And it is rich enough to fund its own growth.

It can also be a hotbed for better ways of living. A fleet of new towns in the Corridor can be designed around autonomous vehicles and small modular reactors. Residents could spend evenings exploring a linear national park running along the new ‘Lovelace’ railway line that links the two university cities.

So this government is right that Ox-Cam can be one of the big bets for the frontier of the UK economy.

People living in the corridor are understandably nervous about lots of development. Many can be convinced it’s worth it if it means a railway station in their town, higher paying jobs and cheaper housing. Or more beautiful nature.

But some won’t be.

That is why every government promises, then fails, to turn the corridor into the UK’s Silicon Valley. The Labour government is already being more ambitious than its Conservative predecessor. But business and policy-makers in the Corridor say it can go much further.

So this paper is about how to go big. And quick. It is a plan to unlock the unholy trinity of local politics, dysfunctional regulation and lack of money that has held us back:

- A single powerful development corporation that can bypass local politics. Parliament should draw a tight line around the corridor, set a target to triple GDP in it by 2050 and then hand over implementation to a single development corporation - the Hawking DevCo - that reports directly to the Chancellor. It should be the supreme planning authority for the corridor drawn by Parliament. It will ask local politicians for advice about how to do things, not permission for whether to do them. This is a nationally significant project; its level of ambition should be set by national politicians.

- A parallel regulatory process to speed it up. The Hawking DevCo should also have powers to discharge environmental regulation in the corridor, taking them from Natural England and the Environment Agency. By having an overarching DevCo that absorbs the gaggle of smaller ones being created along the corridor, it will be easier to hire the talent and create the institutional clout to knock heads together in other regulators, across departments and negotiate with big investors. A single body that coordinates infrastructure across the corridor can also look residents in the eye to say development means better hospitals, more nature and a shorter commute.

- Be self-funding to free up money for the rest of the country. DevCos are money-printing machines because they can buy land, grant planning permission then sell it for a much higher price. In South Cambridgeshire alone, it could capture £30bn of uplift that more than pays for the infrastructure in the area. But to do that, the DevCo needs the financial autonomy to operate at scale and with 25 year horizons. That means allowing it to borrow outside the fiscal rules because it is so low risk, and giving it the tools to negotiate hard on commercial deals. Aggressive land value capture is crucial to make the politics work. Ox-Cam must add to investment in the rest of the country, not subtract from it.

Of course, we need to do the hard grind of reforming existing institutions like Natural England and local planning authorities. But in the meantime, we need to go around - not through - broken processes to deliver on our priorities. This can be a template for projects elsewhere.

Going big on Ox-Cam will be hard. So we have called this Project Hawking. Not only does the project link up the two universities that span the physicist Stephen Hawking’s career, it will require his faith in science and technology to sustain years of hard work.

The Hawking DevCo can be this Government’s Tennessee Valley Authority, a body that defined Franklin Roosevelt’s legacy of using a strong state to get stuff built for the people.

The second half of this paper sets out the piece of primary legislation that would achieve this. It was written with extensive input from planning experts, policy-makers and lawyers.

This article was co-published with Labour Together.

The political case for going big on Ox-Cam

The Ox-Cam Corridor can be the Government’s vision for how we should live in 2050. We will need to build major urban extensions to Oxford and Cambridge to double their populations, as well as new towns in places like Tempsford. This is the opportunity to create better ways of living.

Ox-Cam can be a unique mix of technology and pastoral. A family of four moving to the Corridor could have the highest quality of life in the world. Mum, a mid-career researcher, works in a high paying job building engines for space travel. Dad works on carbon-sink projects in the linear national park. Their family lives in a multi-generational community with tenure-blind housing, shared green spaces, and streets that encourage civic life. Small modular reactors generate low-cost, clean energy. She cycles to work on the safest roads in the country because they were designed for autonomous vehicles and segregated cycling. He commutes to work on the East-West ‘Lovelace’ rail line that connects Oxford and Cambridge

Their amenities pioneer technology being developed at the universities and innovation labs. Their children attend a school built around AI teaching assistants. Their local NHS trust and adult social care providers have applied innovation partnerships with university research centres.

And they participate in community life in new ways. Recommendation engines that run off a digital twin of the Corridor suggest policies for them to vote on via new digital platforms that give a voice to the silent majority that doesn’t have the time to turn up to a planning meeting on a rainy Thursday afternoon.

Figure 1: Mock up on new urban extensions in the Corridor

Source: ChatGPT

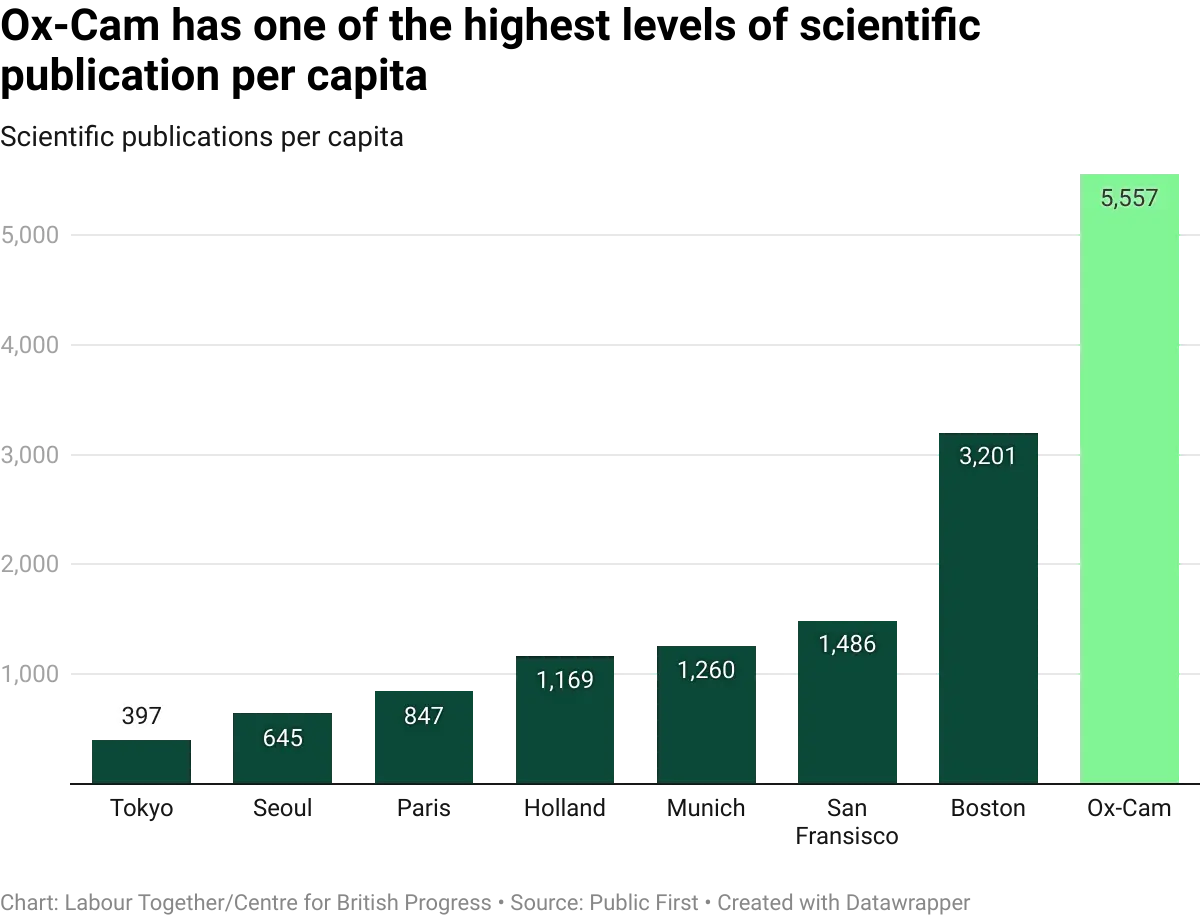

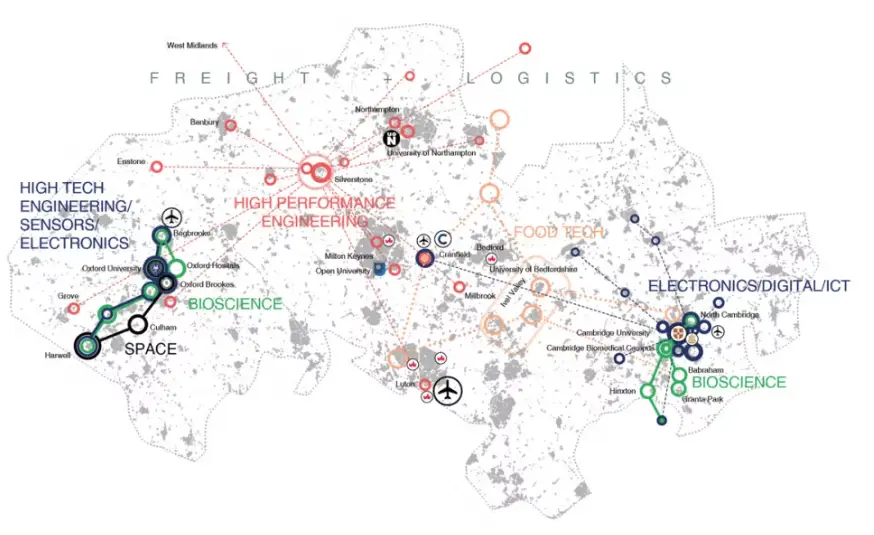

Ox-Cam can also be the flashy crucible for this Government’s innovation and technology strategy. The Prime Minister and Chancellor can tell every business and sovereign wealth fund they meet that the UK is tripling economic activity in one of the most innovative 100-mile stretches of land on the planet. (see Charts 2 & 3)

And it will raise living standards everywhere else too. It is a gateway for the rest of the country to access advanced technology and global markets. Firms that do R&D in the corridor have manufacturing facilities elsewhere. AstraZeneca undertakes research in Cambridge but manufactures in Macclesfield and Mersey. Whittle Laboratory researches jet engines and turbines in the corridor in partnership with Loughborough University and Rolls Royce factories in Derby. Cambridge University has a formal partnership with the University of Manchester to tap into the latter’s strengths in manufacturing. Tracing citations through academic journals shows research started in the region is then developed by universities elsewhere in the country.

Ox-Cam is big enough to strengthen growth and public finances. Raising the Ox-Cam growth rate from 1.5% to only 3% would boost the UK growth rate by 0.1pp in 2030 and by 0.2pp in 2050. That would give the government an extra £10bn in receipts to spend on the rest of the country in 2030, rising to £15b by 2050 (in 2025 prices). If the Ox-Cam growth rate rises to 6%, the average for San Francisco's Bay area over the last twenty years, that increase in receipts rises to £15bn in 2030 and £40bn in 2050.

This growth can also come relatively quickly. The successful clusters in the region are bursting to expand. Densification and expansion of existing cities like Cambridge and Oxford can deliver housing quickly. This can buoy investment and tax receipts as the government does the slow grind of closing the productivity gap between our second cities and the South East.

Figure 2: Ox-Cam has one of the highest levels of scientific publication per capita

Figure 3: Innovative industries in the Corridor

What needs to happen

It’s a tradition that every new government says it will make Ox-Cam the next Silicon Valley. Those grand visions fizzle out for the usual three reasons:

- Local politics. The Corridor cuts across many political fiefdoms, often run by politicians with little interest in growth, so governance is a nightmare.

- The planning and regulatory systems. On top of some unhelpful local authorities, environmental and other regulations make it hard to build a project with so many interlocking parts across housing, transport and utilities in multiple settlements.

- Money. Our current model means the cost of a lot of new infrastructure falls to taxpayers (e.g. trains) or bill payers (e.g. reservoirs). It’s hard to justify putting more national money into the South East when other parts of the country are crying out for investment.

This government is doing much more than the previous government. But companies, universities and policy-makers we have spoken to in the Corridor, along with many across government, believe it needs to be more ambitious to defeat the barriers above.

Going big on Ox-Cam means doing three things:

- An ambitious and simple vision for the corridor set by national politicians.

For example, a target to triple economic activity in the Corridor by 2050, and to fund that with land value capture. This is a nationally significant project, so its vision is set from the centre.

At the moment, we are falling short of even the fairly mild National Infrastructure Commission recommendations from 2017 that the previous government signed up to:

- Housing starts are running at 20-25k pa, below the 40k pa needed to deliver the modest BaU target of an extra 1mn homes by 2050

- East West Rail is only scheduled to be complete by the mid-2030s and even that looks unlikely at current pace. Plans for a new road to connect the arc have been cancelled

- No new reservoirs have been granted planning approval despite water being a major constraint on development

- A powerful cross-corridor entity to implement that vision that sits outside normal government processes.

That means a development corporation that is responsible for its own financing so it can plan at 25 year horizons rather than be micro-managed by Whitehall. It is the supreme planning authority where necessary in the Corridor. So it can designate areas where it takes direct control for planning, and be a backstop decision maker that can accelerate or overrule decisions by local authorities elsewhere.

It is also a one-stop regulator to streamline environmental regulation. It has taken on responsibilities from regulators like Natural England for these purposes. Its purpose is to balance competing legal obligations itself to achieve its aim of tripling GDP in the corridor, not spend years getting sign-off from different quangos.

It has the scale to hire some of the best planners, real estate experts and lawyers in the world, giving it the political cover and resources to manage opposition by local actors. It is led by somebody with executive experience whose authority comes from their monthly meeting with the Chancellor, as well as their planning powers and budget.

At the moment, the planned delivery mechanisms are fragmented, or don’t exist. We are taking time to consult on a development corporation in Cambridge because we inherited a process that was broken by previous governments. The New Towns Taskforce recommended further DevCos in Oxford, Milton Keynes and Tempsford. Even if we eventually set those up, these DevCos - along with potentially the 9 others recommended by the Taskforce - will all be competing for scarce talent and resources. Without excellent leadership, the Treasury will be understandably reluctant to give them the financial freedom they need.

- More powerful land value capture tools to make landowners pay for infrastructure.

There is lots of scope for land value capture. It’s unfair that landowners enjoy huge windfalls from planning permission and infrastructure built by the public sector and generated by the skills of the workers. With more ambitious planning, we estimate £30bn of potential land value capture in South Cambridgeshire alone - i.e., it could comfortably pay for all the infrastructure that that area needs: £7bn for East-West Rail, £3bn for the Fens reservoir and £2bn for a new tram system in Cambridge.

At the moment, there is no overarching funding plan. The Spending Review gave East West Rail £2.5bn, and there has been another £400m for homes in Cambridge and re-opening a small railway extension outside Oxford. But much more money is needed to purchase land and build infrastructure for new towns and urban extensions. A single new town may require upfront capital investment of more than £15bn.

It could all be funded by land value capture. But, under the current DevCo system and especially for big projects like new towns, that requires development corporations to borrow. But the UK does not have the fiscal headroom for a large expansion in their borrowing. Unlike the EU, we include development corporations within our fiscal rules.Given that DevCos are basically money-printing machines - they can buy land, grant planning permission, then sell it for x100 multiples - that is unwise. That is why no EU country has our approach to fiscal accounting.

The delivery plan

The previous section argued the case for going big. This section is about how you would actually do it.

At a high level, there needs to be primary legislation that does three core things:

- Drive development of the Corridor from the centre by creating a single body with planning powers, budget and a leader that reports directly to either the Prime Minister or Chancellor. The planned DevCos could be subsidiaries. This avoids disrupting their work, but also creates a cross-corridor body with much more clout.

- Give the Hawking DevCo powerful planning and land value capture tools so Ox-Cam can be self-funding.

- Create a streamlined, pro-active process to apply environment rules for Hawking DevCo projects.

Drive development of the Corridor from then centre by creating a single body - the Hawking DevCo

The Hawking DevCo would be bigger and more powerful than any before. The goal is to enable a DevCo as they were designed to be in the 1950s and 1960s, before they were saddled with swathes of legislation that restricted their freedom of action. The Hawking DevCo is more powerful than DevCos envisaged in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill (PIB).

Mission: Parliament specifies its mission to triple economic activity in the Corridor by 2050 - a simple economic mission to minimise the scope for judicial review (JR) from multiple duties - and to fund that with land value capture. It reports directly to the Chancellor. It has discretion about how much it consults local stakeholders. Local governments have no formal vetoes. This gives it the incentive to deliver quickly.

Powers: Parliament specifies a tight geographical area along the corridor over which the Hawking DevCo has strong planning authority. Within that area, Hawking DevCo can specify places where it will take over planning. It can overrule any decision by local authorities within its boundaries that it believes undermines its mission. It also takes on responsibilities for environmental regulation from national regulators like Natural England and other statutory consultees in the Corridor. So it has powers to deliver quickly without having to get permissions from multiple bodies.

Its size and powers give it the clout in Whitehall to work with departments on skills, transport and other enablers for the region, as well as with global investors to fund infrastructure and housing.

These powers are set out in more detail in the next section.

Budget: The DevCo needs the funding to sit outside normal fiscal processes. It is crucial that it has the freedom to plan and commit on 20+ year timelines. It can use its planning powers to cut deals with private investors, or directly use its Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) powers to buy undeveloped land, grant planning permission and build infrastructure, then sell the land to developers at many multiples of the purchase price. Hawking DevCo therefore needs the ability to borrow at scale from capital markets to fund the initial purchase. There is a strong case for following the EU precedent of excluding development corporations from the fiscal rules given they are low risk and funded by the sale of land, rather than taxes. By giving Hawking DevCo powers to fund itself, it has the incentive to control costs and does not keep coming back to the Government for more money.

Personnel and structure: A strong leader who is an experienced developer. That leader must be able to recruit the best people, unbound by civil service hiring and performance processes.

To deal with the granular nature of land and infrastructure at different locations and to create competition you would probably need three subsidiaries within the DevCo (e.g. Ox, Central and Cam). The Cambridge Growth Company and the Oxford Growth Commission have done valuable preliminary work, so they would be subsidiaries of the new body, able to benefit from its powers. This avoids disrupting their work, but also creates a cross-corridor body with much more clout with Whitehall and investors. Each subsidiary may need 100 or so people to have the scale that could act independently, sitting under a single cross-corridor leader.

The legislative vehicle: A short piece of primary legislation is required to deliver the above. A bill would create powers to create DevCos like the one proposed in this paper. When it is in force, the Secretary of State (SoS) then lays before the Commons an instrument setting out the red line boundary of a new DevCo, and Parliament approves it by an up/down vote, thereby creating the DevCo. This strips away the delays and JR risk from the current consultation requirements for creating a DevCo that were put in place in 2016. The two-step Bill and subsequent vote is necessary to ensure Parliamentary passage while avoiding the cumbersome Hybrid Bill procedure.

The idea is to pass a short bill to quickly set up an entity with all the powers it needs on planning and land value capture. The DevCo will rapidly make deals with landowners and other partners while drawing up a strategic plan. Waiting for government departments to agree on a strategic plan would take years and entail endless fighting about what it should contain.

Give the Hawking DevCo powerful planning and land value capture tools so Ox-Cam can be self-funding

The Corridor is a large and complex area, so Hawking DevCo needs a wide range of planning and land value capture tools to compulsory purchase and master plan in some places (e.g. a new town), to work in partnerships with developers in others (e.g. smaller settlements) or just incentivise more private development (e.g. densification in existing settlements).

The DevoCo will have powers to enable development:

- Specify the areas within the boundaries drawn by Parliament in which it will take over all planning applications from an Local Planning Authority (LPA).

- Grant planning permissions, Transport and Works Act Orders and all other relevant permissions. Hawking DevCo can choose to continue with the Development Consent Order (DCO) process for the Bedford to Cambridge train link (application not planned until 2027) or to simply grant the necessary planning permissions and other orders, after getting any approvals from the streamlined regulatory process described below.

- Call in applications for planning permission and impose conditions for value payable by developers on those applications. The existence of this power is a low cost way to encourage LPAs to approve applications on conditions they can set themselves.

- Set new National Development Management Policies, Special Development Orders, Permitted Development rights, building regulation guidance and planning policies within areas it designates, use of which by the applicant which may be conditioned on a fee based on a fee schedule it sets.

- Create an overall Strategic Environmental Assessment instead of Environmental Impact Assessments for individual projects, as now happens in the EU.

The DevCo will have a range of powers to do ambitious land value capture to fund its activities. This will be a flexible toolkit because tools depends on the type of project:

- Compulsorily purchase land that is not allocated for development in a current or proposed local plan at a modest premium to existing use value, subject only to a requirement to state the intended use of the land, without the need for a spatial plan or consultation.

- Implement land readjustment as done in Japan, Germany and other countries. Land is assembled into one large lot for streets to be laid and infrastructure connected. The Devco would then reallocate a portion of the land to the original owners, and retain the remainder for new infrastructure or sale to fund the process.

- Designate areas that will benefit from transport improvements where it will set a modest annual charge on the value of undeveloped land in order to incentivize development or sale of land to the DevCo. Around two-thirds of EU member states levy annual taxes on undeveloped land, making the principle entirely mainstream in Europe. Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Greece, and Poland all apply a tax on land. Some go further still, applying targeted surcharges on land hoarding: France, Spain and Portugal impose higher rates on buildable land that remains undeveloped in high-demand areas to prevent land hoarding and encourage productive use. Within the DevCo this tax could be up to 0.5% per annum, but only on the portion of value that exceeds agricultural value.This would be a “Harberger tax”: landowners would value their own land, and the DevCo would then have the power to initiate CPO within 12 months of that valuation at that value plus 10% with no further right for the landowner to renege on their own valuation. As a result of the 0.5% tax on their estimated land value, the owner has an incentive to avoid inflating the price of their land. The tax also encourages a fast built-out rate.

- Make partnership agreements with landowners (including equity shares) and expressly condition planning permission on value transferred by the landowner. (This can be phrased in statutory drafting as a power for landowners to offer benefits.)

- Exercise highways powers in areas it designates and impose congestion charges (or require a share of them) in any area that will be benefitted by the infrastructure that it intends to generate, including Oxford and Cambridge themselves, with a portion paid to the local authority and a portion kept by the DevCo to improve transport.

Create a one-stop system of environment approvals specially for the Hawking DevCo

The Bill should empower SoS to create a new dedicated one-stop regulator sitting within Hawking DevCo. Its duty is to improve nature and the environment in the area while finding ways to deliver infrastructure in the fastest and most practical ways possible.

- That specialist regulator should have concurrent jurisdiction with all existing environmental regulators to exercise any of their relevant powers, including monitoring and enforcement, in relation to any project of the DevCo and to take over any or all of their functions in areas it designates. This includes those of Natural England and the Environment Agency, and the power to directly ask Parliament to vote on bespoke Habitats Regulations which will apply in those designated areas. It will therefore have the power to offer an attractive one-stop-shop to councils.

- It will work in cooperation with Hawking DevCo, to ensure an environmental win-win and deliver at pace. Unlike the Environment Agency, it will be outside civil service pay schemes, so it can recruit the best people; it will have teams inside the DevCo, so it will have better relationships and culture; and it will have the power to create different habitats regulations for its purposes, enabling hardcore strategic mitigation. The EU-UK TCA commits the UK to non-regression on environmental matters. But the appetite of the EU to bring a legal challenge will be low because this proposal will cover a small geographic area, insignificant to the EU in the context of the broader UK-EU relationship, and because the proposed strategic mitigation within a small area is not very different from a place based mitigation.

The Hawking DevCo will also have the powers to build necessary infrastructure to manage the environmental impact of development in the corridor, including:

- Impose charges on development granted permissions in future in areas designated by the DevCo that it intends to benefit (including in and around Oxford and Cambridge). Those charges can be used for its purposes, including better water and other infrastructure and improving the environment.

- CPO, connect to and take other steps in relation to water infrastructure to deliver at speed.

- Build any other infrastructure for the benefit of the Corridor, including through partners, and require any utility operator to allow it to be connected to their system in reasonable time for a reasonable fee, provided that such requirements will not increase bills to existing consumers.

The Bill could also create a rapid full-merits appeals system against decisions by the DevCo on CPO, charging and planning, to replace the system of judicial review. The appeals would be similar to tax appeals to the First-tier Tribunal, with (i) a statutory presumption that the original decision stands unless the appellant displaces it, and (ii) a judicial duty to uphold/repair the decision where it can lawfully do so, if the DevCo is willing to accept the amended decision. This is similar to the French judicial review system where judges can repair decisions and allow projects to proceed without full redetermination, remedying any issues and speeding up delivery.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]