Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Harnessing exceptional talent for the national interest

- 3. Exceptional talent routes work – but are underused

- 4. Recommendations

- 5. Authors

Summary

- A small number of exceptional individuals generate disproportionate benefits for productivity, innovation and job creation in the UK. Attracting these exceptional people (scientists, founders, creatives, technologists) is critical to Britain’s long-term growth and resilience.

- The UK already has two strong “exceptional talent” routes — the Global Talent Visa (GTV) and High Potential Individual (HPI) visa — with high satisfaction and good labour-market outcomes, but they are currently being underused.

- Overall volumes are small (a few thousand visas a year), not because applicants are rejected but because many potential candidates never hear about or understand these routes.

- Four steps can be taken to increase the uptake of these routes, and the attraction and retention of exceptional talent:

- Advertise the existing routes: Create a single, clear “Exceptional Talent” website online, actively market these visas abroad, and equip employers and universities with guidance.

- Adopt a contribution-based ILR accrual system for temporary pathways: Let years spent on temporary work and study routes count towards settlement when people meet contribution benchmarks (e.g. salary or tax paid), so highly contributive migrants can progress to ILR.

- Reduce upfront costs for exceptional routes: Reduce or restructure the UK’s very high upfront costs (particularly the Immigration Health Surcharge) by waiving, exempting or spreading payments over time for exceptional talent and their families.

- Pilot new GTV endorsing bodies: Broaden GTV endorsements beyond academia by piloting new endorsing bodies (e.g. venture capital funds, R&D organisations) that can recognise excellence in industry and frontier technology, with time-limited pilots and caps.

Harnessing exceptional talent for the national interest

When immigration works, it works for Britain. The Huguenots who fled persecution helped make London a city of commerce and craft. German miners, invited by Tudor monarchs, seeded early industrial expertise. Engineers such as Marc Isambard Brunel built the nation’s infrastructure. Polish and Czech airmen defended British skies, while immigrant scientists drove breakthroughs in radar, codebreaking, and modern physics. From banking houses to laboratories, foreign talent has helped build a more inventive, prosperous, and resilient nation.

Public concern about immigration today is not irrational. It reflects legitimate expectations of fairness, order, and democratic control. However, when voters can clearly see how a person contributes to the country’s security and prosperity, support for welcoming that talent is consistently high.

Most people are not opposed to all migration; they are opposed to a system that feels chaotic and unfair. They want the government to reduce pressures on housing and public services, to uphold the rules, and to ensure that immigration is clearly in the national interest. Within that framework, there is broad acceptance (and often enthusiasm) for attracting exceptional individuals whose work creates jobs, advances discovery, and strengthens Britain’s global position.

Britain has an opportunity to gain a global competitive advantage by encouraging exceptional workers to come to the UK. The future of the British economy’s position in the world depends on winning in a number of a few key industries such as artificial intelligence, life sciences and advanced manufacturing. Industries that depend on highly-educated graduates in computer science, chemistry and engineering.

Traditionally the United States has been the leading destination for such talent. But the climate of fear and uncertainty from a large crackdown on illegal immigration and erosion of institutional norms has reduced the US’s pull for many, and even led to an increase in American emigration. Britain could stand to benefit.

A small number of individuals have an outsized impact on the economy and society. Research consistently shows that exceptional talent (whether in science, technology, entrepreneurship, or the creative industries) produces spillovers that lift productivity, innovation, and job creation. Of the United Kingdom’s 100 fastest-growing companies, 54 have a foreign-born co-founder. For a medium-sized country like the UK, this kind of talent should be a core part of a serious growth strategy. Britain’s advantages lie in advanced research, high-value services, and innovation. In all of these areas, outstanding people are the critical input, and they are often highly mobile.

Recent governments have recognised that exceptional global talent is central to Britain’s growth model. Over the past few years, ministers have repeatedly described an ambition to make the UK “the best place in the world” for scientists, founders and innovators, and have introduced a set of policies to attract them, including expanding the list of universities that qualify for the high potential individual visa and fast-tracking settlement for high earners. These routes are well-designed, and evidence suggests they are attractive. However, much more could be done to increase the uptake of existing visa routes by exceptional talent.

Exceptional talent routes work – but are underused

Britain already has two routes designed to attract exceptional talent: the Global Talent Visa (GTV) and the High Potential Individual (HPI) visa. Both are well-regarded and deliver strong outcomes. But uptake remains modest, and awareness is low. A targeted scaling of these routes could support British ambition in science, innovation, and economic growth, leading, in turn, to sustained, increased contributions to Britain.

Global Talent Visa (GTV)

The GTV allows recognised leaders or potential leaders in academia or research, arts and culture, or digital technology, to work in the UK without a job offer, after securing an endorsement from bodies like UKRI or The British Academy (or via the prestigious prize route). It doesn’t require sponsorship by an employer (meaning it allows workers to switch jobs and be self-employed easily) and can lead to settlement after 3 or 5 years, depending on your field and how you’re endorsed.

There are four Global Talent visa pathways: A) Academia & Research (sciences, engineering, humanities, social sciences, medicine)

B) Arts & Culture

C) Digital Technology

D) Prestigious Prizes (no endorsement needed)

|

The GTV route is effective in attracting exceptional talent, but it skews heavily towards academia, and overall uptake remains modest (~6,500 visas per year). Home Office reviews show:

- High satisfaction with both endorsement and visa stages (around 90% satisfied overall).

- Flexibility and path to settlement were the biggest attractions.

- When surveyed, ~98% were in some form of employment; most felt their job matched their skills; 56% had an annual salary of between £31,200 and £51,999

- Fields breakdown: Academia (67%), business & commerce (14%), creative industries (11%).

- More than 80% of visa holders said the GTV influenced their decision to live and work in the UK, and 50% who said it influenced them to a great extent.

High Potential Individual visa (HPI)

The HPI visa is a short-term UK work route for recent graduates of selected top global universities. It requires no job offer or sponsorship, and permits 2 years’ stay (3 with a PhD). It can’t be extended and doesn’t lead directly to settlement, but visa holders can switch to another route (e.g. Skilled Worker or GTV) if eligible.

The Home Office did an evaluation of the HPI in May 2025 and concluded that the visa had “good satisfaction and outcomes but low uptake”:

- ~4,500 main HPI visas (plus ~600 dependents) were granted May 2022–June 2024, modest compared with other routes.

- 78% were in work at the time of survey; 46% earned over £40,000, 27% over £50,000, and 12% earned over £75,000, indicating strong labour-market outcomes, especially given most of those on the visa are young (63% were 18–29).

- 66% planned to stay in the UK longer than their current visa; among those planning to stay, 75% were eyeing a switch to Skilled Worker, and 29% to GTV.

The HPI university list was extended to the top 100 universities by the government in November 2025 and a cap was introduced of 8,000 applications per year.

Both the GTV and HPI are considered by the Home Office to be successful. The Home Office Wave-2 evaluation signals very high satisfaction with endorsement and visa stages and concludes that the route has had a positive impact on making the UK more attractive for talented migrants. The HPI evaluation finds the vast majority had a positive application experience, most were in work, salaries skew high, and two-thirds plan to stay longer.

However, both evaluations suggest that awareness is a barrier to uptake of these visas. Limited of awareness could be why application numbers are low and approval rates high – a signal that many qualified candidates may never apply:

- In the year to June 2025, the Home Office issued 6,566 Global Talent visas and 2,012 High Potential Individual visas – a small share of total work visas (a combined 3%).

- For Global Talent, once an applicant has endorsement, visa approval rates are typically 85–90%+. The same pattern is reported across various evaluations and reviews: endorsement is the hard part; the visa itself is usually granted.

Recommendations

We propose four ways to increase uptake of these exceptional routes:

1) Advertise the existing routes

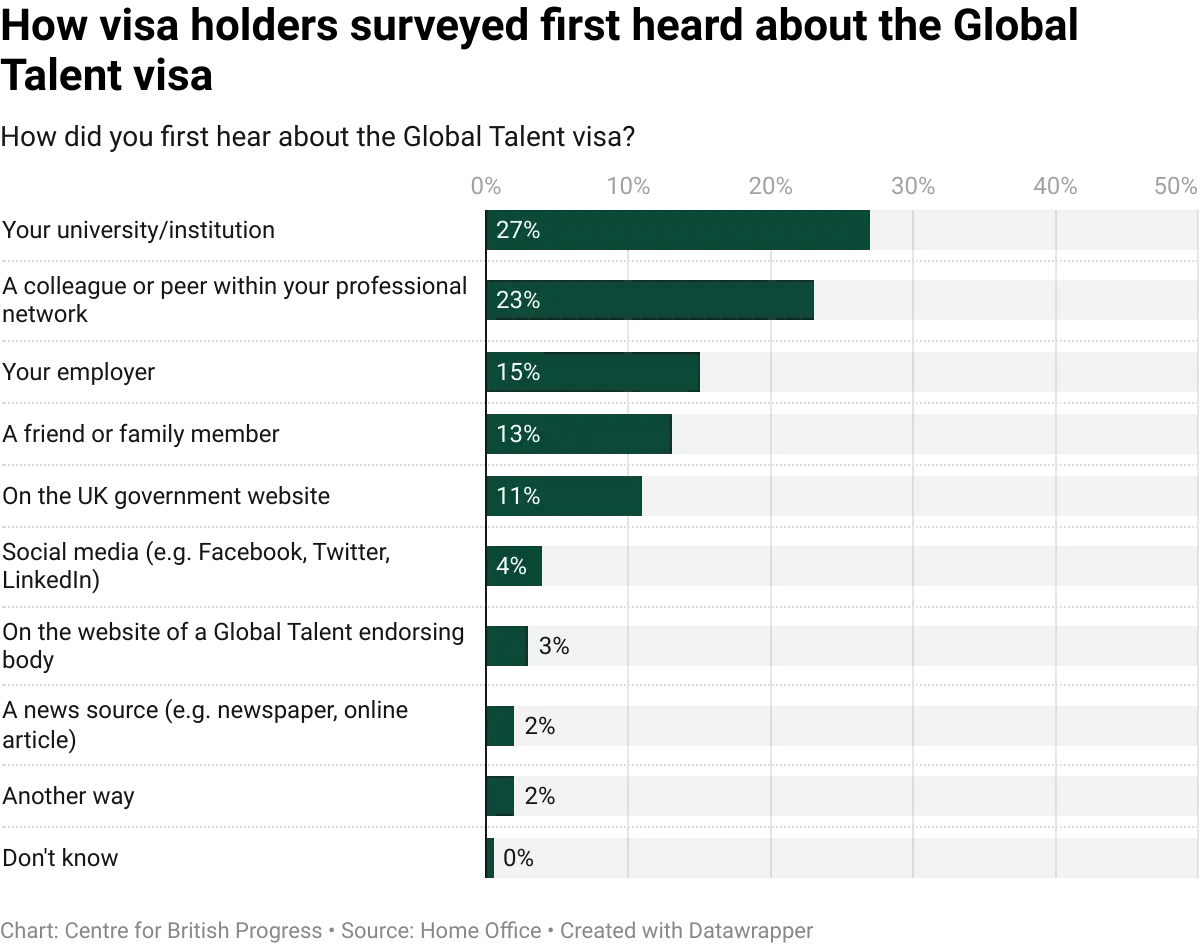

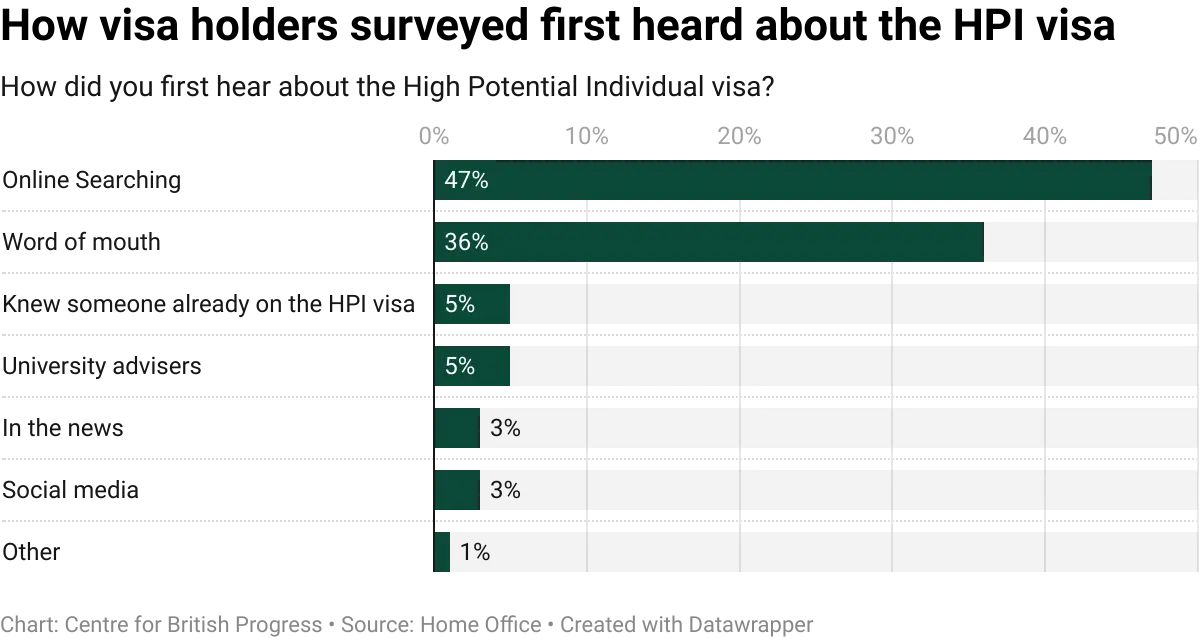

Limited awareness of the visa categories is likely one of the primary reasons for low uptake. Many of those on the GTV and the HPI visa are learning about the visa through word of mouth, suggesting current broadcasting channels like the government website are likely not cutting through.

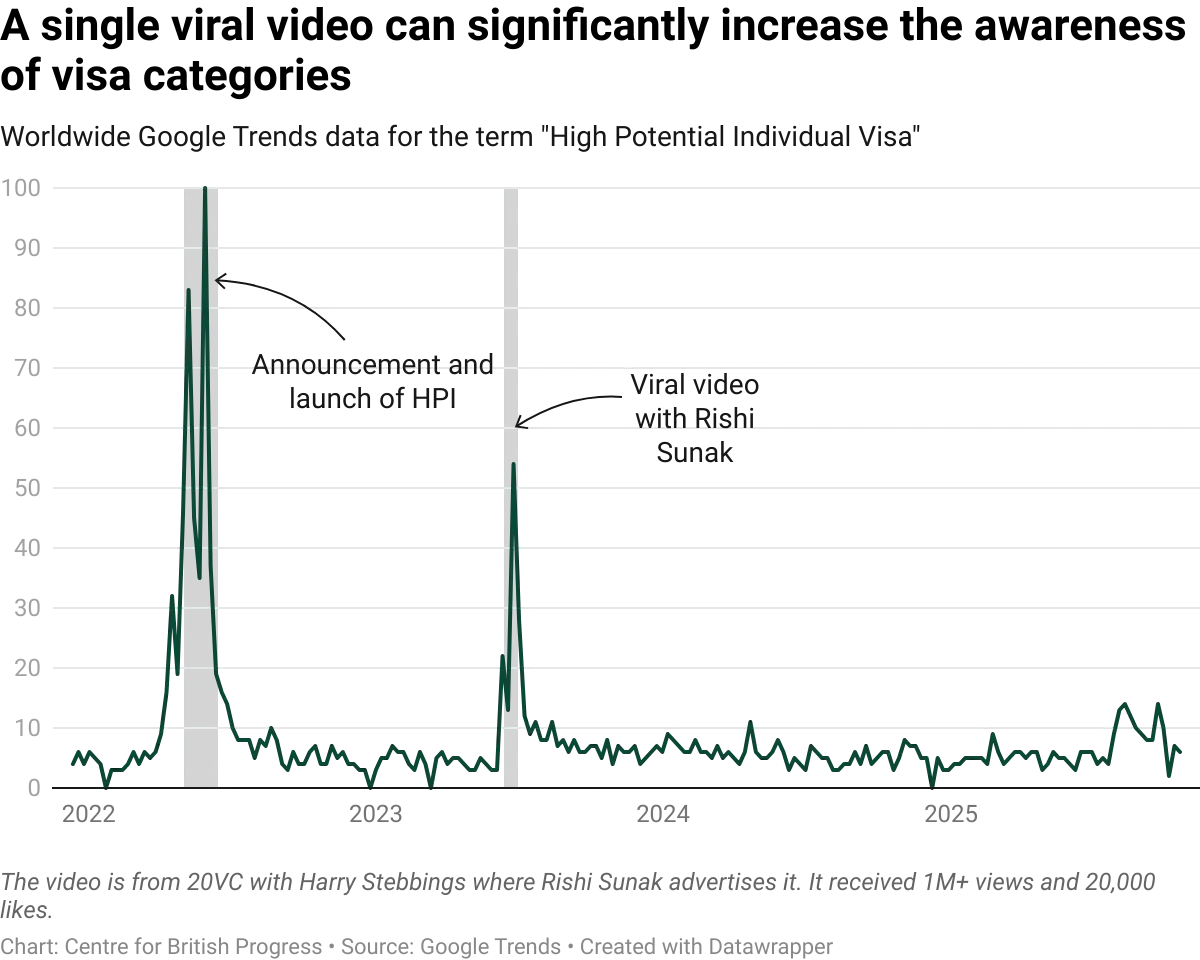

But we have good evidence that advertising these routes works. Interest in the HPI visa peaked at launch (May 2022) and then spiked again in June 2023 without any policy change, after a widely shared 20VC interview clip featuring Rishi Sunak with Harry Stebbings. The clip drew 1M+ views and ~20,000 likes on YouTube, and Google Trends recorded a matching surge in searches for “High Potential Individual visa.” Simple, well-targeted exposure materially lifted awareness – exactly the effect a coordinated campaign could replicate.

Employers can also help with raising awareness. The GTV evaluation finds uneven familiarity among universities (the employers of many academic applicants), with some HR teams offering clear advice and others providing limited or inaccurate guidance. The evaluation explicitly recommends stronger, standardised guidance for university HR. The HPI evaluation echoes this: visa-holders report “low employer awareness” as a hiring barrier.

To attract more exceptional talent through these visas, we should advertise the routes by:

- Building a single “Exceptional Talent” website. The Government should build a single "Exceptional Talent" landing page with clear signposting to endorsing bodies and relevant advice. Unlike the current website (which is ugly, not very easy to navigate, and not targeted at high-skilled migrants), this new page should be built as an attractive product and have user-friendly tools like easy-to-use eligibility checkers.

- Launching a targeted advertising campaign that directs people to the “Exceptional Talent” landing page.

- The government should use targeted advertising on platforms such as Google and Meta to advertise the visas to relevant applicants. Modern advertising tools allow targeting by geography (e.g. Cambridge, Massachusetts), education level (e.g. Master's, PhD) and interests (e.g. STEM content), meaning the effort could focus on priority groups, which will save on advertising costs and limit the chances of an unsustainable surge of application numbers.

- The Prime Minister and Ministers in his cabinet should also actively promote the visa pathways with foreign media.

- Publishing and circulating explainer pages for employers, universities and funders. Two landing pages should be produced as explainers for employers, universities and funders. The pages should be designed to give employers confidence that they can hire individuals on these visas without providing sponsorship.

- The HPI explainer pages and written materials targeted at students should be sent to international offices in HPI universities.

- The GTV explainer should be sent to British university HR offices, with particular focus on the universities identified by the GTV evaluation as having low familiarity with the visa route.

- The British Council should host regular in-person events at HPI universities to advertise the exceptional talent routes and signpost applicants to the “Exceptional Talent” website. These events should be delivered in partnership with careers services and international offices, feature Q&A sessions, and provide clear, practical guidance on eligibility, application steps, and progression to longer-term routes such as Global Talent and Skilled Worker visas.

2) Adopt a contribution-based ILR accrual system for temporary pathways

Those on temporary routes (like the HPI visa) receive no credit towards settlement. For many high-skilled migrants, this reduces the overall attractiveness of those routes. Currently, a highly skilled graduate on the HPI earning £100,000 and paying full UK taxes for two years accrues no years towards ILR, despite contributing a vast amount to the country. This disconnect between contribution and settlement eligibility suggests that there must be a better model of ILR accrual for exceptional talent.

Under this proposal, each year on a temporary UK visa route (like the Graduate, HPI and YMS visas) would count as one year toward ILR if, during that year, the individual meets at least one of the following contribution benchmarks:

- Salary benchmark: the individual earns a minimum gross salary at or above the Skilled Worker salary threshold in force for that year.

- Tax/National Insurance benchmark: if the individual’s combined annual Income Tax and National Insurance contributions are at least equal to the amount typically paid by an individual earning the minimum gross salary at or above the Skilled Worker threshold.

- Voluntary top-up benchmark: where income is below that level in a given year, the individual may make a voluntary top-up payment so that their total Income Tax, National Insurance and voluntary contribution reach the same amount typically paid by an individual earning at or above the Skilled Worker salary threshold.

Years in which an individual does not meet any of these benchmarks would not count towards ILR. In practice, this would make routes like HPI, Graduate and YMS more attractive without changing their temporary nature, for applicants who are not contributing at or above the level expected from those on non-temporary routes.

3) Reduce upfront costs for exceptional routes

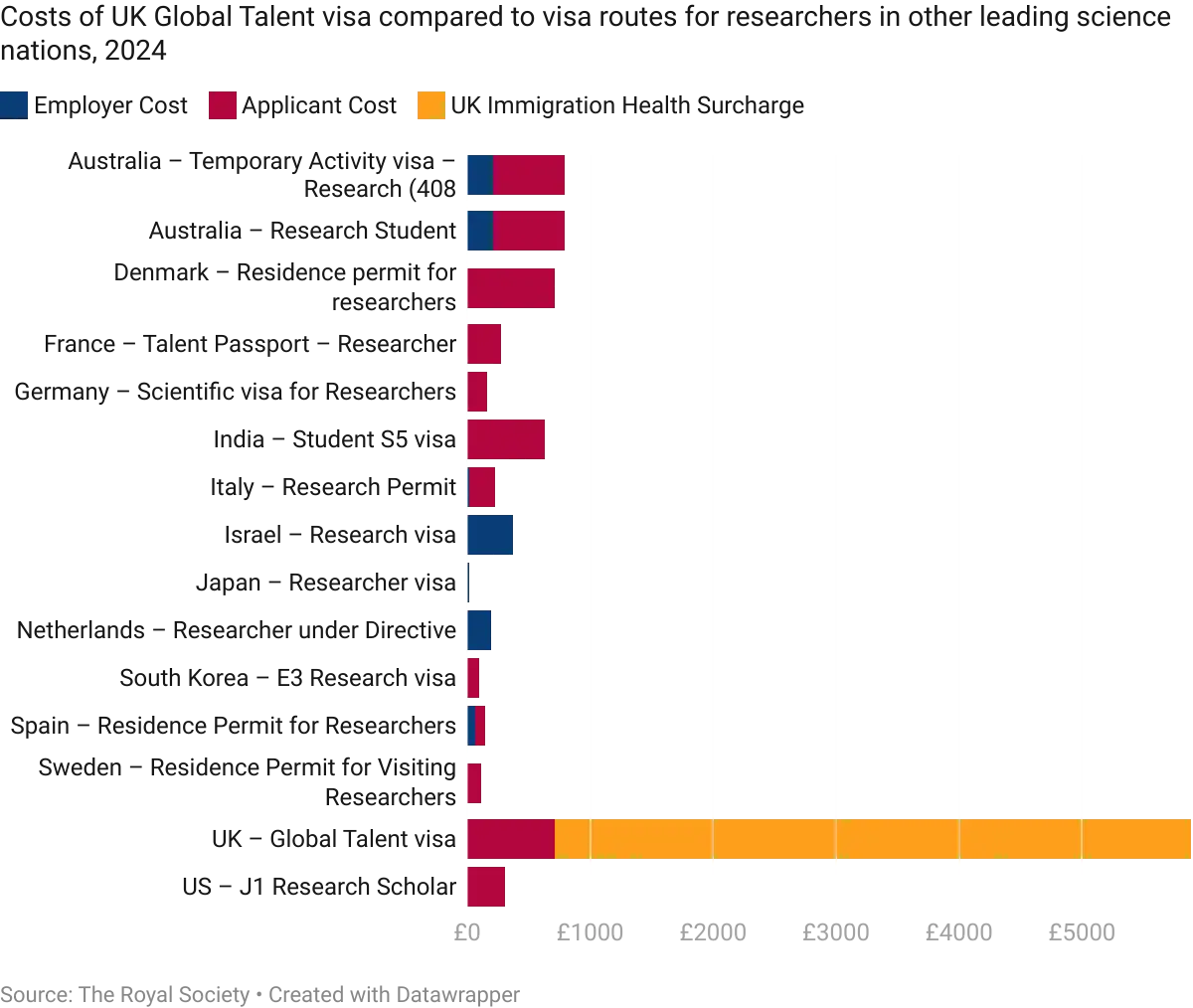

The UK imposes some of the highest upfront relocation costs on highly skilled migrants in the world. A major component of this burden is the Immigration Health Surcharge (IHS). Under today’s rules, most long-term visa applicants must pay the full IHS for the entire length of their visa at the point of application, a requirement that can run into many thousands of pounds, especially for those with dependants.

What is the Immigration Health Surcharge (IHS)? The IHS is a fee that most non-UK nationals must pay when applying for a visa to stay in the UK for more than six months. The payment is made up front, covering the duration of the visa leave being applied for. Once paid, the visa-holder is entitled to access the NHS on broadly the same basis as a UK resident for the length of their stay. The surcharge is currently £1,035 per person per year for most visa routes. Because it must be paid in full when applying, the cost can run into several thousand pounds for longer visas or for applicants with dependants. |

This creates a significant deterrent for exceptional talent who might want to move to the UK. Home Office evaluations show that the IHS upfront burden weakens the attractiveness of Britain’s exceptional talent routes:

- Global Talent visa – Wave 1 evaluation (2022): 59% said the IHS was unfair; several interviewees hadn’t expected to pay all years up front and consequently reduced the years they applied for or borrowed money to cover it.

- Global Talent visa – Wave 2 evaluation (2024): 65% said the IHS was unfair; dependants’ fees could push total costs over £10,000, described as “challenging” and “demotivating”.

The UK is also an international outlier. Other advanced economies do not impose large lump-sum healthcare charges on highly skilled migrants. Instead, they spread costs over time or tie them to employer-funded insurance:

Country | Health Cost Requirement for Work Visas | Upfront Cost? |

|---|---|---|

United Kingdom | NHS Surcharge: £1,035 per person/year | Yes (£5,175 for 5 years per person) |

United States | Employer/private health insurance required | No (paid monthly) |

Germany | Public/private insurance required | No (monthly payments) |

Australia | Overseas Visitor Health Cover (private insurance) | No (monthly payments) |

Canada | Provincial healthcare or private insurance | No (monthly payments) |

At precisely the moment Britain is competing for researchers, founders, technologists, and innovators, the IHS design makes the UK less attractive than its peers. A more proportionate approach would maintain NHS sustainability while removing unnecessary barriers for the very people the system aims to attract.

There are four options to soften the deterrent posed by high upfront visa costs:

- Waive the IHS for exceptional routes (e.g., Global Talent)

- Exempt applicants with private health insurance (protecting NHS capacity while assuring the public that costs are not being shifted to taxpayers)

- Allow central government cross-charging (e.g., through DSIT/DBT), making applications free at the point of use for priority cohorts

- Move from an upfront lump sum to annual or monthly payments

NHS Surcharge Exemption Scenarios

Scenario | Private Insurance Coverage (%) | IHS Revenue Collected | Estimated Costs of NHS Use | Net Government Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Current Policy (Full IHS) | 40% (current estimate) | £23.3M | £14.4M | £8.9M |

Full IHS Exemption (No Private Insurance Requirement) | 40% (no change) | £0M | £14.4M | -£14.4M |

Voluntary Private Insurance for IHS Exemption (30% voluntary IHS payments) | 70% (40% existing + 30% new) | £7.0M | £11.7M | -£4.7M |

Full IHS Exemption + Mandatory Private Insurance (100% take-up) | 100% (all GTV holders) | £0M | £9.0M | -£9.0M |

Even the least interventionist change (shifting to monthly or annual payments) would materially improve the attractiveness of exceptional talent visas. It would reduce risk for applicants, align the UK with international practice, and remove one of the most frequently cited psychological and financial barriers to choosing Britain.

4) Pilot new GTV endorsing bodies

Most GTV holders are in academia (67%), largely because many endorsement routes are designed around peer-reviewed academia or UKRI funding. Exceptional non-academic talent has few natural routes.

World-class founders, engineers, applied researchers, and technologists at independent labs or frontier companies often cannot show the peer-reviewed outputs expected by academic panels. Many work on proprietary or NDA-constrained projects, making it harder to evidence contribution under academic criteria. Non-academic STEM talent is often pushed toward the Digital Technology pathway, which currently relies on a single endorsing body. The evidential standards differ, the endorsement capacity is limited, and many profiles do not map cleanly to “digital tech” even when their work is in national-priority fields such as AI, advanced materials, or biotech.

Together, these factors mean the UK is over-selecting for academic excellence and under-selecting for applied and industrial excellence, despite the fact that the latter is critical for productivity growth, industrial strategy, and frontier innovation. This over-representation of academic talent is likely one of the reasons why the average salary of those on the GTV (~£57,000) is lower than one might expect: academia pays less well.

The Government should run a pilot with a new crop of endorsers for 12–24 months to test impact and, where endorsers succeed at attracting exceptional talent, extend it. New endorsers (of which the Government should consider top VC firms and non-profit R&D organisations) should be focused on non-academic talent.

The pilot should:

- run for 12–24 months

- include approximately five new endorsers, each with a fixed visa cap (e.g. 500 visas per 24 month period)

- use the same remuneration model as existing Academia & Research and Arts & Culture endorsers, where they are paid an agreed annual amount plus a per-application payment

- undergo review at pilot end, with successful endorsers scaled, and underperforming endorsers retired

The pilot would expand capacity, broaden the talent funnel, and ensure that the GTV route serves the full spectrum of exceptional individuals – not only those already inside university systems.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]