Table of Contents

- 1. Summary

- 2. Frontier Growth is Powered by Exceptional (Often Foreign) Talent

- 3. Building The Next Idea Forge

- 4. We Are Not As Competitive As We Think

- 5. The Exceptional Talent Office

- 6. Appendix

- 7. Authors

- 8. Acknowledgements

Summary

To achieve national renewal and sovereignty, Britain must compete in the global race for world-class scientific and technical talent. With the United States facing a potential exodus of scientists, and as China, the EU, and Canada launch aggressive recruitment drives, Britain must position itself as the premier destination for frontier innovators.

- Highly-skilled immigrants – particularly those in STEM fields – have an outsized impact on economic growth and technological innovation. They have been found to be responsible for about 36%–37% of US innovation. Under 15% of UK residents are foreign-born, but 39% of the UK's fastest-growing startups have at least one immigrant co-founder.

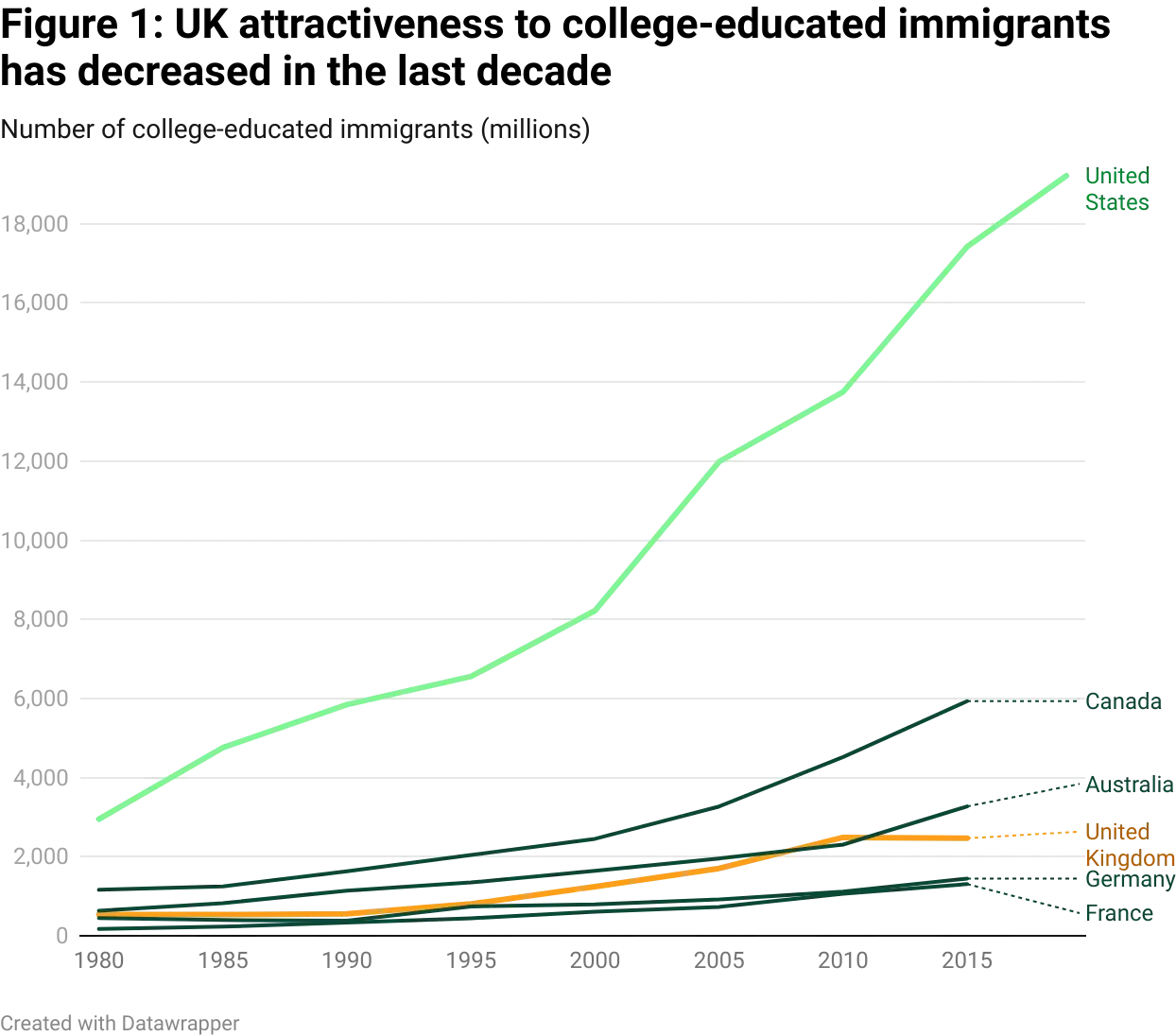

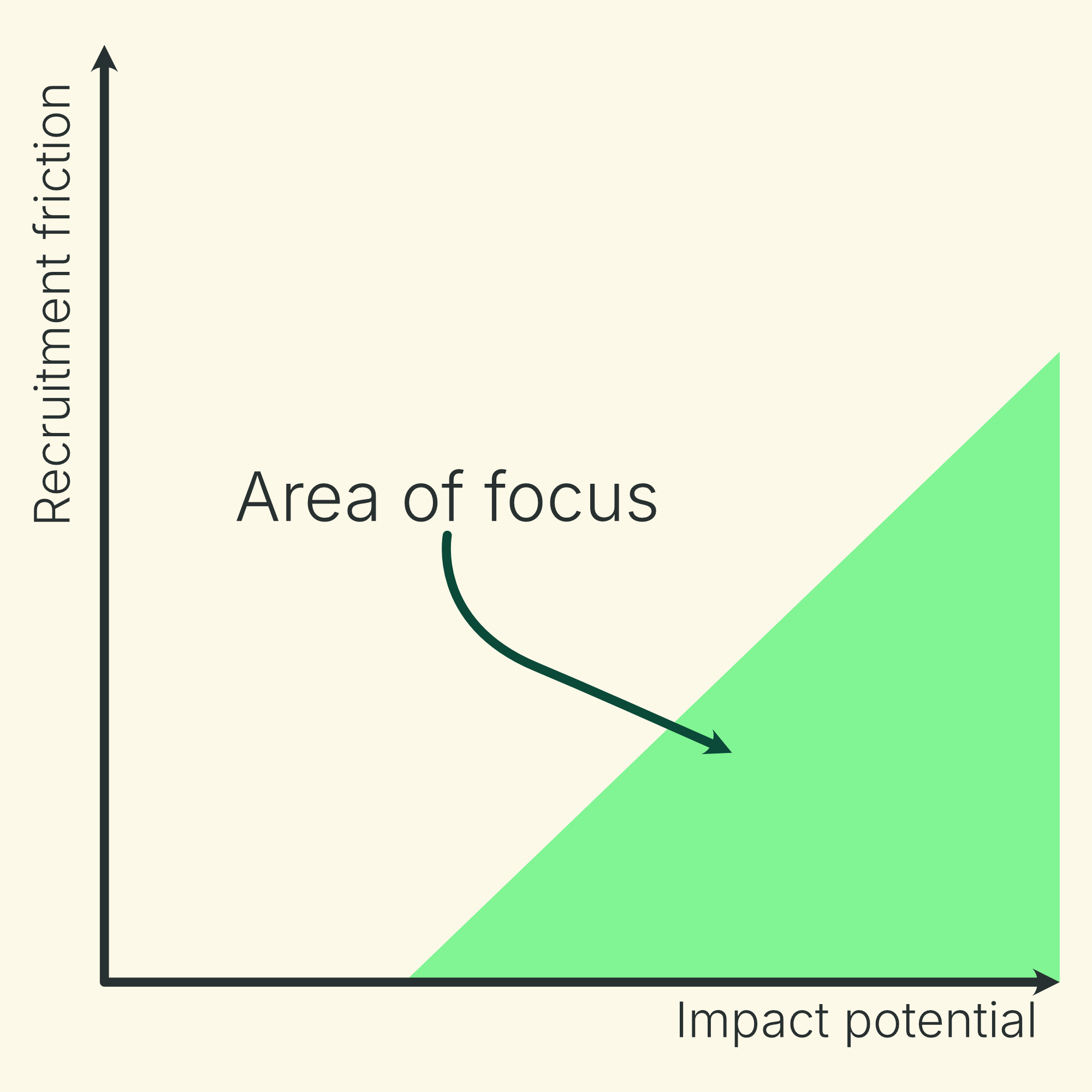

- However, Britain’s attractiveness to researchers has stagnated. We are also one of the biggest exporters of AI talent in the world (with the majority of researchers moving to the US), implying that we train top talent but struggle to retain it.

- The Government’s AI Opportunities Action Plan recommends establishing a “headhunting capability on a par with top AI firms to bring a small number of elite individuals to the UK.” To deliver on this recommendation, the government should establish an Exceptional Talent Office responsible for proactively head‑hunting exceptional individuals to relocate to Britain.

- The purpose of the Exceptional Talent Office is to compete for the world's best talent in science, technology, and business. The ETO will find and recruit the people who will make the breakthroughs and build the largest companies of the 21st century, and ensure they do it in Britain. This is in service of economic growth and prosperity for the British people.

- To deliver on this mission, the Exceptional Talent Office should:

- Have the flexibility to design packages to incentivise exceptional talent to relocate to Britain. It should offer a relocation package for talent and dependents in exchange for a 3‑year residency commitment - with the flexibility to tailor incentives on a case-by-case basis.

- Cover a broad range of disciplines, moving beyond AI to the top talent across all STEM fields (for example, fusion, quantum, or engineering biology).

- Target the diaspora as well as international talent.

- Provide a fast-tracked ETO visa (capped at 100 a year) for ETO participants and their dependents.

- Leverage philanthropic co‑funding so that a meaningful share of the ETO operating budget does not cost the taxpayer.

- To avoid possible failure modes, the ETO should:

- Have the right leadership – The ETO must be led by individuals with the credibility, networks, and operational skills to compete for talent with top-tier tech firms and elite scientific institutions. At the top, the government should appoint a respected external “Talent Tsar” to serve as the public face of the programme - someone with the stature to pitch directly to world-class recruits. Day-to-day operations should be run by an experienced talent operator with a track record in headhunting for frontier science or deep tech roles.

- Have a supportive institutional home – The ETO exists to respond to economic and geostrategic needs. It should be housed in the centre (as a joint no.10 + DBT or DSIT unit) and report to the Prime Minister because it cuts across national competitiveness, immigration, industrial strategy, and R&D. The competition for exceptional talent should not be impeded by “macro” immigration concerns and the Talent Tsar needs political cover to take chances on uncredentialled, exceptional talent.

- Get the operating model right – The ETO should have the flexibility to explore various methods to identify top talent and develop deep relationships to talent pools. Approaches could include leveraging intelligence from the UK Science and Technology Network and using a forthcoming RAND analytics platform to spot emerging scientific leaders. It should also explore replicating and refining the search approaches used by top executive‑search firms and elite tech‑company recruiting teams.

- Only target genuinely exceptional talent – Given the bar, success should be measured by quality not quantity of recruits. This strategy rests on the assumption that the economic and strategic spill‑overs from recruiting even a small number of world‑class researchers or engineering leaders outweigh the programme’s costs. Too strong a focus on the number of people recruited may incentivise the unit to work its way down the list and start targeting people that are not genuine ‘super stars’.

Frontier Growth is Powered by Exceptional (Often Foreign) Talent

There are economic and strategic reasons to prioritise the attraction (and retention) of exceptional talent.

A small number of top performers move the frontier. The very best scientists, engineers, and founders sit on the extreme right tail of the talent distribution curve: a handful of researchers account for a disproportionate share of citations, breakthroughs and high-value patents, and star inventors build better companies than their peers. This “heavy-tail” pattern arises because ideas are non-rival and digital technologies let the most capable individuals leverage vast datasets, capital and networks. When one such person joins or stays in a domestic cluster, they not only generate their own discoveries but also raise the output of everyone around them through mentorship, collaboration, and magnetism that attracts further talent and investment.

These spillovers translate into tangible gains for ordinary households. Firms led or influenced by top-tier talent tend to expand quickly, creating jobs in engineering, operations, and supply chains, while the higher wages they pay ripple through retail and services. Their innovations lower consumer prices, seed entirely new industries and – as with mRNA vaccines or AlphaFold – deliver public-good benefits.

Top STEM talent has an outsized impact on the economies of host countries. An influx of skilled workers increases the stock of knowledge producers, which in theory raises the rate of idea generation. Immigrants also produce positive externalities which benefit national economic productivity – for example, by sharing techniques or inspiring new research directions. This can shift an economy to a higher long-run growth path.

A recent NBER study estimated that highly skilled immigrants are responsible for about 36%–37% of aggregate US innovation, once one accounts for spillover effects on natives. Evidence from the UK is more sparse, but studies have shown similarly positive results at a regional and firm level. Notably, while under 15% of British residents are foreign-born, 39% of the UK's fastest-growing startups have at least one immigrant co-founder.

In particular, foreign talent powers frontier AI research – an area that is increasingly important for economic and geostrategic objectives. In the US, ~70% of the top AI talent is foreign-born. At OpenAI, 10 of the first 50 technical and research staff were from Poland. In Britain, ~77% of top-tier AI talent completed their undergraduate degree in another country.

Because the social return of talent rises so sharply with individual quality, policies that target and retain rare performers offer high pay-offs.

Building The Next Idea Forge

History shows that human talent can shift the balance of global power.

The US and, to a lesser extent, the U.K. benefited enormously from the influx of European scientists and intellectuals fleeing war-torn or politically unstable homelands before, during, and after the Second World War. This influx of talent boosted scientific capacity and innovation ecosystems. Foreign inventors made foundational contributions in fields such as rocketry and aeronautics (which underpinned the US space program), advanced weapons systems, Bletchley Park’s wartime code-breaking, early computer science, and nuclear research. One recent study showed that the influx of German Jewish chemists into the US led to a 30% increase in native patenting.

Recognising the strategic opportunity, the US government, through initiatives like Operation Paperclip and the Soviet Scientists Immigration Act of 1992, actively “headhunted” international talent, recognising its importance to geopolitical competitiveness (and, to a lesser degree, economic growth). The UK ran a similar programme, Operation Surgeon, after World War II, which attracted 100 out of 1,500 targeted scientists and technicians.

For all the talk of trying to recreate Silicon Valley, too little attention has been played to the role of immigration in its successes. Between 2006 and 2012, nearly 44% of high-tech firms in Silicon Valley were founded by immigrant entrepreneurs. By the late 1990s, immigrants constituted approximately one-third of Silicon Valley's engineering workforce.

The very establishment of Silicon Valley as a cradle of innovation is a story of immigration. The "Traitorous Eight” laid the foundation for Silicon Valley after leaving Shockley Semiconductor to found Fairchild Semiconductor – two of the eight were immigrants and another two were children of immigrants. Their work directly led to the creation of Intel, National Semiconductor, and others. Intel’s eventual rise was guided by Andy Grove, a Hungarian refugee whose leadership helped make it one of the most important tech companies in the world. Morris Chang, an immigrant from China, played a crucial role at Texas Instruments before founding Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which has become a global leader in chip manufacturing. A diaspora of scientists and engineers established the ecosystem that has dominated technology for the last fifty years.

Today, the UK is presented with an opportunity. Our biggest competitor for top scientific and technical talent, the United States, has significantly cut research funding and created an inhospitable environment for even highly skilled immigrants. A Nature survey of 1,200 US-based scientists show that 75% are actively considering posts abroad, citing political polarisation, funding uncertainty and immigration friction.

Less salient is the emigration of Russian and Ukrainian talent, but since the start of the war the region has experienced significant brain drain. About ~18.5% of Ukrainian scientists had left the country by late 2022. While at least 2,500 Russian scientists have left the country to work abroad since the outbreak of war. Programmes like the Arnold Landau Fellowship, run by the London Institute of Mathematical Sciences, have begun to take advantage of this phenomena, but they have not yet reached a scale commensurate with the opportunity.

Were a wider exodus to occur, Britain would not automatically win. There is an incredibly competitive global market for STEM talent and for AI researchers in particular. Countries like China, the EU, and Canada have launched aggressive talent-attraction drives. If the UK wants to compete with these nations (among others), it will likely need to make a concerted effort to attract exceptional talent.

We Are Not As Competitive As We Think

There are many reasons why people decide to upend their lives and move to a new country. People move for a better salary, the strength of the local ecosystem, tax rates, citizenship, or even the weather. Many of these factors are not within the power of a government and/or cannot be changed in a short time period.

On factors the government can influence, the UK has historically been relatively weak. Moving to the UK is incredibly expensive for top talent. A researcher on the Global Talent Visa (GTV) faces ~580% higher upfront fees than the average in other leading science nations. This means that a family of four coming to the UK on a five-year GTV is liable to pay £20,974 upfront. It can take up to 8 weeks to process a GTV, compared to the 2 weeks in Canada.

A myriad of factors have meant the UK’s attractiveness has decreased in the last decade:

We’re not only struggling to attract top international talent; we’re also losing the skilled people we already have. We are the biggest exporter of AI talent in the world. In 2024, we had a net flow of -559 AI researchers.

Our relatively poor performance is a cause for concern, considering the outsized impact this top talent has on our economy, society, and international competitiveness. The government should consider a set of policies that directly targets this talent pool – an imperative that may be especially timely given shifting geopolitical dynamics. The Exceptional Talent Office is one mechanism that aligns with this goal.

The Exceptional Talent Office

The UK should establish an Exceptional Talent Office (ETO) - a specialist unit tasked with proactively identifying and relocating world-class scientific and technical talent to the UK. Crucially, it should not be used as a way to fill vacancies for individual employers. Its aim should be to secure exceptional people for Britain's national advantage: founders, entrepreneurs, technologists, research scientists, and future business leaders who want to build, experiment, and create within the UK’s innovation ecosystem.

The ETO should function as a talent-first vehicle for national renewal. Its core bet is that recruits should be targeted for their exceptional promise and not to fulfil specific vacancies or needs. Even if recruits do not yet have fixed roles or ventures in mind, their exceptional calibre means they will - if given the right environment and support - go on to found companies, push the boundaries of science, and drive future waves of economic growth.

To achieve this, the ETO should:

1) Cover relocation costs for individuals and their dependents, in exchange for a three-year residency commitment - with flexibility to tailor additional incentives based on individual needs and opportunity.

The ETO should offer a relocation support package to remove friction for exceptional individuals considering a move to the UK. The unit should retain the flexibility to provide incentives on a case-by-case basis. The process of attracting talent should be seen as a negotiation – not all recruits should be given the same offers.

Where employers do not cover relocation costs, the ETO could consider covering costs such as flights, shipping, housing search assistance, visa/legal fees, and temporary accommodation upon arrival. Some further incentives in the ETO’s toolbox could include a X-month cost-of-living allowance, compute vouchers, and funding for PhD programmes.

The ETO should act as package negotiator and deal-closer. That means: connecting top talent to British based companies (especially where the company is a startup), facilitating negotiations for fractional appointments with host universities; helping secure ring-fenced Catapult centre access; providing introductions to venture or translational-grant finance; and, where justifiable, brokering private–public compensation top-ups funded in part by philanthropy.

This offer should be tied to a three-year minimum residency commitment, enforced by a claw-back clause. If the individual leaves the UK before completing three years of residency (excluding short absences for trips), they must repay a proportion of the relocation support on a sliding scale:

- Departure in Year 1: repay 100% of support

- Departure in Year 2: repay 66%

- Departure in Year 3: repay 33%

- Completed 3 years: no repayment

At the final stages, for high-priority individuals, the Prime Minister should call ETO recruits to understand what they need to succeed in the UK and pitch them on joining the programme.

2) Broaden scope beyond AI to include exceptional talent across all STEM fields.

AI talent deserves a focus because the UK is in a global bidding war for the small pool of engineers and researchers who can push state-of-the-art models forward. But narrowing ETO to AI alone would be short-sighted.

Scientific breakthroughs - and the companies they spawn - almost always arise from cross-pollination: quantum hardware accelerates machine-learning, new battery chemistries enable autonomous robotics, and advanced microscopy drives drug-discovery algorithms.

By scouting exceptional talent across materials science, synthetic biology, energy systems, mathematics and more, the ETO creates a portfolio of complementary capabilities. This broader remit both hedges against shifts in the tech landscape and maximises the opportunity for serendipitous collisions that turn disparate ideas into transformative UK-based ventures.

3) Recruit both internationally and from the diaspora.

The ETO should look at the entire global talent map and target talent irrespective of their location and nationality. Much of the top talent will be in the US, but attracting this talent to the UK may be particularly challenging (getting someone to leave a senior position at OpenAI, for example, is very difficult). This does not mean the ETO should dampen their ambition.

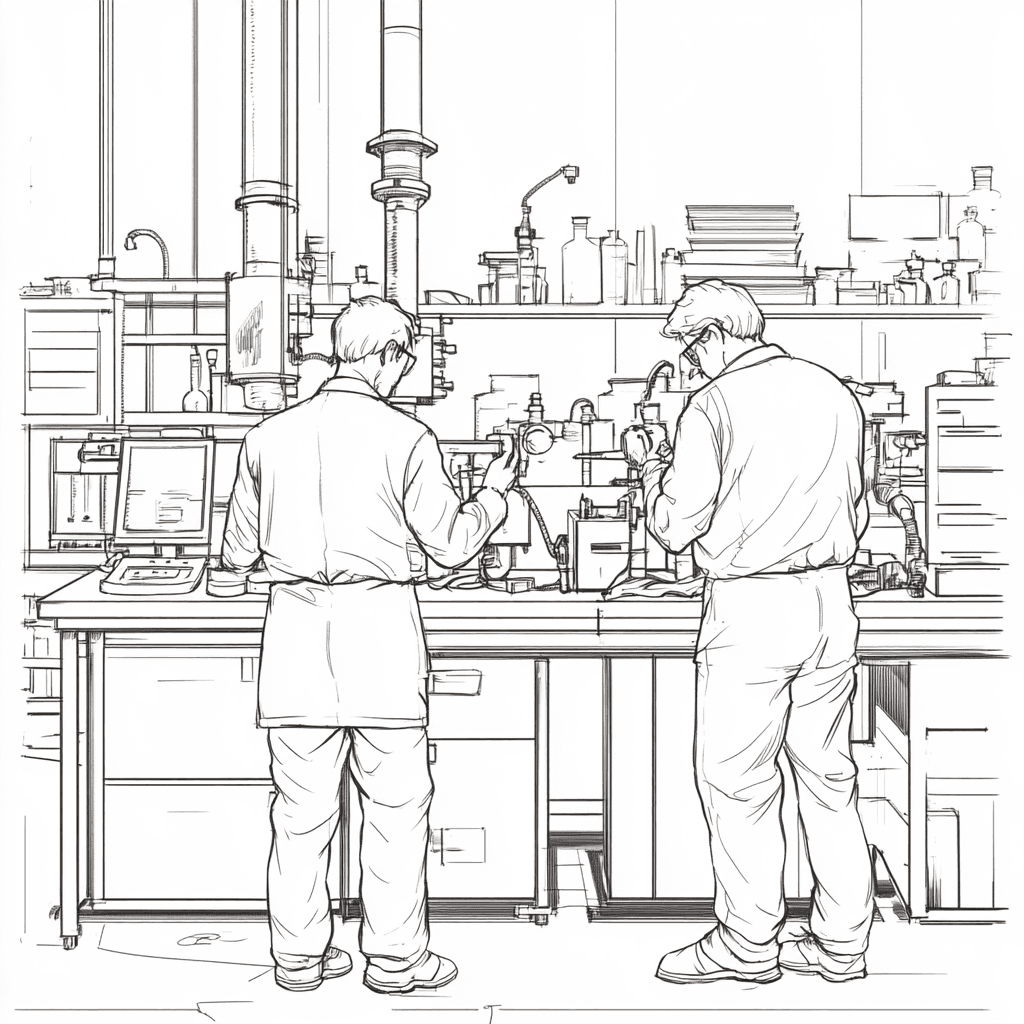

A Proposed Prioritisation Scheme For The ETO

One should think of the ETO’s pipeline as a 2 × 2 matrix: impact potential (the value a recruit could create over a decade) on one axis and recruitment friction on the other. The ETO should prioritise high-impact individuals that have low recruitment friction.

4) Enable fast, flexible visa routes for foreign talent.

The ETO should control its own annual quota of up to 100 visas, that could cover the recruit plus dependents. However, this visa quote should be seen as a backstop as most ETO recruits would be eligible for other, pre-existing visa pathways. Candidates whose circumstances call for other visa types - for example, undergraduates requiring student visas - could use existing routes, but any application carrying an ETO endorsement should be routed through a “green-channel” process that delivers a decision within two weeks.

Talent Identification Methodology

Ultimately, this unit will have to compete with top AI firms and quant hedge funds. It should, therefore, have – at a minimum – similar headhunting capabilities to these elite institutions.

The unit should retain the flexibility to explore various methods to identify top talent. It should also be able to draw upon external expertise by working with other groups (internal and external to government) to identify talent. For example, it could explore leveraging:

- The RAND analytics platform to spot emerging scientific leaders

- The Global Talent Fund’s BIG programme that targets Olympiad medalists

- Referrals from trusted individuals (e.g. technical talent already based in the UK) and technical/scientific institutions like ARIA

- Intelligence from the UK Science and Technology Network or Tech Envoys

Funding Model

The ETO should have a core budget of c. £15 m p.a. This would cover core operating costs (including any tools used in the talent identification stage), recruit relocation costs, and any additional incentives. Funding should be earmarked for a 5 year period, after which the government should review the programme and decide whether or not to continue the model.

It should target ≥20 % of funding (£3m p.a.) from philanthropic co‑funding. Philanthropy would likely not want to cover core operating costs, but could be used to top-up grants to recruits.

Delivery Roadmap

Table 1: A Roadmap to Deliver the ETO

Phase | Milestone | Date |

|---|---|---|

0. Strategic alignment & spending authority | Collective agreement secured via the relevant Cabinet Committee, outline Business Case (OBC) endorsed by the Minister and submitted to HM Treasury | End Q2 2025 |

I. Political & budget sign-off | Full Business Case (FBC) receives HM Treasury spending approval (Spending Authority letter issued), senior Responsible Owner (SRO) confirmed | Start of Q3 2025 |

II. Set-up | Founding director appointed | End of Q3 2025 |

V1 operating model finalised | Start of Q4 2025 | |

III. Student fast-track window | Wave 0 outreach to undergrad–PhD prospects** | Nov–Dec 2025 |

IV. Pilot operations | “Alpha cohort” – 3–4 high-impact low-friction recruits (secondary aim is to battle-test processes) | Jan–Mar 2026 |

V. Year-one delivery | KPI: 10 relocations | By Dec 2026 |

VII. Scale-up | Review of relocation package offers and the operational model to establish that the programme is successfully attracting talent | Year 2 (2027) |

30 relocations | ||

VII. Steady state | 50 relocations | Year 3 (2028) |

VIII. Review | Review of the programme as a whole and kill / no-kill decision | Year 5 (2031) |

**We should expedite outreach to undergrad–PhD recruits because UK universities lock most postgraduate offers nine months before term; Cambridge and Oxford close many PhD channels by early December. To ensure the first student cohort lands in September 2026, ETO must start targeting students as early as August 2025. Missing this deadline pushes arrivals back a full academic cycle, meaning the students ETO selects after January 2026 would not reach UK soil until September 2027 - a one-year opportunity-cost. Recruits in the Alpha cohort and beyond should not be limited to undergrad–PhD students.

Avoiding Failure Modes

In order to avoid failure modes, the ETO need to:

1) Have the right leadership

Leadership must signal excellence from day one and must not resemble a typical government appointment. Instead, ETO leadership should mirror the elite institutions it seeks to rival: top-tier VC firms, AI labs, and executive search teams.

a) A respected external figure as "Talent Tsar" (1 day/week)

A ministerial appointment of a high-profile figure from the worlds of science, technology, or entrepreneurship - someone with name recognition and an elite network - should serve as the ETO’s external-facing champion. This person should be empowered to:

- Open doors with top researchers, founders, and labs globally.

- Directly pitch candidates in the final stages on relocating to the UK.

- Signal credibility to recruits and potential philanthropic funders.

b) Operational director with headhunting or talent acquisition expertise

The Operational Director should be externally appointed. The ETO must be run day-to-day by someone with a proven track record identifying and closing elite talent deals. Ideal profiles include headhunters from a leading executive search firm with experience placing technical leaders or talent leads at a frontier science investment fund, incubator, or accelerator (e.g. A16Z, YC, or Insight).

This person should be tasked with building out the operational toolkit (processes, outreach channels, tools) and shape ETO’s "deal closing" capacity.

c) Lean internal team of civil servants

Initially, ETO should operate with a core team of 2–3 dedicated civil servants. This team should scale as needed based on recruitment volume and operational complexity.

2) Have a supportive institutional home in the centre

The ETO’s programme should be seen as one that responds to economic and geostrategic needs. It ultimately is not solely a question of immigration policy, industrial strategy, nor R&D. It should be seen as a high priority strategic play that has long-term national competitiveness implications.

Housing the ETO in the centre (as a joint no.10 + DBT or DSIT unit) and giving it a direct reporting line to the Prime Minister anchors the programme above departmental silos. The competition for exceptional talent should not be impeded by “macro” immigration concerns and the Talent Tsar needs political cover to take chances on uncredentialled, exceptional talent.

3) Focus on the right talent pools

The ETO should focus its effort where (a) the UK offers a credible pull-factor and (b) the marginal benefit of intervention is highest. There are various ways ETO could fail in its talent identification methodology; for example by:

- Defaulting to easily accessible metrics like ranking candidates almost entirely by easily counted proxies - citation tallies, h-index, patent counts, Forbes 30-Under-30 lists.

- Limiting outreach solely to the US, Western Europe, or existing Oxbridge networks leaves huge pools untapped. Tier-1 Indian Institutes of Technology, IISc Bangalore, KAIST, Tsinghua–PKU “talent programmes,” São Paulo’s state universities, and Southeast Asian AI hubs (e.g. Singapore’s AISG fellows) have graduate researchers who rival their OECD peers yet face greater friction in securing lab space, compute, or unrestricted visas.

- Outsourcing the methodology to a university or academic institution that is not at the frontier of the scientific field they are recruiting into.

- Overrating seniority/credentialism and ignoring exceptional emerging/unconventional talent – e.g. IMO winners, incredible undergraduates, and university drop-outs.

- Putting people off by “working down a list”, cold calling, and ticking off names, instead of refining and personalising outreach based on the candidate and general response dynamics.

- Focussing only on academic researchers when gaps exist in e.g. engineering and product delivery talent.

Ultimately, ETO will likely be most successful where it uses a number of different talent identification methods that provide it with wide inbound.

4) Only target genuinely exceptional talent

The ETO’s value proposition is that one exceptional person is worth more than ten competent ones. A Nobel-calibre chemist who spins out two drug-discovery firms, or a GPU-systems architect who founds the next Graphcore, can generate billions in private investment, hundreds of skilled jobs, and durable UK strategic leverage. By design, therefore, the programme should judge success primarily on who relocates, not how many.

If ETO is judged primarily by how many scientists it moves each quarter, the unit will be under constant pressure to hit numerical targets - an incentive structure almost guaranteed to erode standards over time. Recruiters faced with a flat pipeline and a looming KPI may redefine “exceptional” just enough to clear their monthly quota. Each incremental compromise is rationalised as temporary, but compounded across cycles it produces a cohort whose collective impact is no longer meaningfully different from that of existing visa routes. Therefore, numerical throughput must be a secondary dashboard item, capped at ~35% of the ETO’s performance score at the review stage in Y5.

Appendix

Table 1: STEM Talent Attraction Schemes Around the World

Region | Programme / Action |

|---|---|

China | 1. “Qiming Plan” (启明计划) – the quiet 2023 relaunch of the former Thousand Talents programme, now targeting AI, semiconductors and quantum science.

2. Municipal / institute top-ups that stack on the national award

3. AI Innovation & Computing Zones (Beijing, Shanghai-Zhangjiang, Chengdu, Hangzhou, Shenzhen and others)

|

The EU |

|

Canada |

|

Singapore |

These programmes contribute to the national goal of tripling the AI practitioner pool to about 15 000 by 2029-30 under NAIS 2.0. |

United Arab Emirates |

|

Saudi Arabia |

|

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Ben Johnson, Louise Dunsby, Nitarshan Rajkumar, Laura Ryan, Sienna Rothery, and Jack Watson for comments, advice, and feedback.

For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]For more information about our initiative, partnerships, or support, get in touch with us at:

[email protected]